During the baseball season of 1883 the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League fielded a Black man named Moses Fleetwood Walker as their starting catcher. That season was Walker’s first in the league, and he rapidly became one of its better catchers, hitting well and helping to lead the Blue Stockings to the league title. That championship prompted the Blue Stockings to transfer lock, stock and barrel from the Northwestern League to the American Association, which, along with the National League and the Union Association, was one of the 3 major leagues in operation at the time. With the shift to the American Association, the Toledo team brought their catcher with them; thus, when he stepped on the field for the 1884 season Moses Walker became the first Black man[1] to play in the major leagues. There would not be another until 1947, 63 years later, when two men, one Black and one White, took it upon themselves to break the major league color barrier. Those two men were Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, and this is their story.

_____________________

In 1943 long-time Major League Baseball executive Branch Rickey became the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. At the time, and even still, Rickey was famous for his development of the professional baseball farm system, which he used to turn his team, the St. Louis Cardinals, into perennial National League contenders across the 1930s. A deeply religious man, Rickey had been haunted for years by an incident that occurred when he was coaching the Ohio-Wesleyan University baseball team in 1910. While in South Bend, Indiana for a game, Rickey took his team to a hotel, only to find that the establishment would not allow a Black player on the team named Charlie Thomas to stay there. Rickey told the hotel manager that unless he relented on allowing Thomas to stay he would move his entire ball club to a different hotel. In negotiating with the man, Rickey suggested that Thomas be allowed to sleep on a cot set up in his room, and in the end the hotel manager reluctantly gave in. Rickey relates that he later found Thomas in their room, sitting on the cot and crying. As he watched, the young man started using one hand to tear at the other, as if he was trying to scratch his skin off. Alarmed, Rickey asked Charlie what he was trying to do to himself. Through tears Thomas said, “It’s my hands. They’re black. If only they were white, I’d be as good as anybody then, wouldn’t I Mr. Rickey? If only they were white.”

“Charley,” Rickey responded, “the day will come when they won’t have to be white.”

Since that day in 1910 not one Black man had played in the majors. Now, in 1943, on taking over as general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Branch Rickey decided it was time for him do something about it—and that’s exactly what he did.

Under no delusions about the task he was setting out to accomplish, the Brooklyn GM knew the road ahead would be tough. Though certain he was morally right in his mission, he also understood there would be defiant opposition, perhaps even violence, used to stop him. He would need to find a Black player who not only had the necessary skills to play in the big leagues, but who also had the temperament and the courage to take the inevitable abuse and not strike back, something Rickey realized was essential. Any attempt by his player at retribution would be used to justify why Blacks weren’t up to the mark, and shouldn’t be allowed in the majors. Whoever Rickey’s Black player would be would need to understand that too, and be capable of doing it.

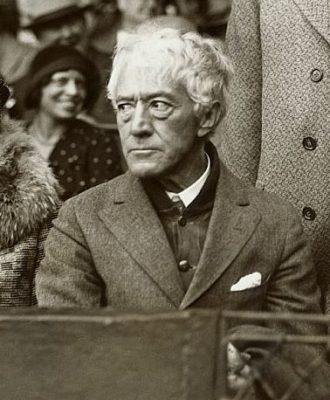

The first step for Rickey was to inform his board of directors of his intentions. Famous for his eloquent loquaciousness (sports reporters used to refer to his office as “The Cave of the Winds,”) his request was approved, and so he began his quest to find the player he needed. One of the major barriers Rickey knew he would face existed in the form of then Major League Baseball Commissioner, Kennesaw Mountain Landis.[2]The only commissioner MLB had ever known; Landis had been handed the post in the wake of the 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” scandal[3] by team owners desperate to restore public trust in their game. Since then, for 24 years he had ruled baseball with an iron hand, enforcing the unwritten policy that the game should be reserved for white players only—a policy supported by virtually every team owner. Between Landis and the racist owners, that unwritten policy was more like a brick wall, ultimately forcing Blacks to create and play on their own teams—the Negro Leagues.

The barrier to baseball’s integration presented by MLB’s commissioner in the end would come to nothing due to a combination of circumstances; the first being that on November 25th, 1944, Kennesaw Mountain Landis died. Landis’s replacement as commissioner was an ex-senator from the state of Kentucky named Albert “Happy” Chandler.[4] Initially most observers assumed that Chandler would simply carry on the policies of his predecessor, but an interview of him, conducted by the famous Black sports writer Wendell Smith[5]in the spring of 1945, indicated that Chandler’s views on Black ballplayers were considerably more liberal than those of the iron-fisted Landis. “If a Black boy can make it on Okinawa and Guadalcanal,” [6]Chandler told Smith, “hell, he can make it in baseball!” Thus, by 1945, to that extent at least, the stars were aligning for Rickey’s plan.

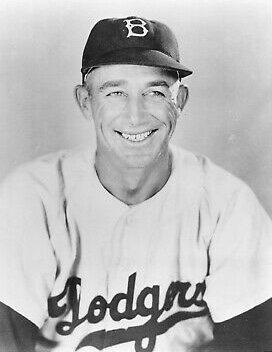

It was early in 1945 that Rickey called his assistant and chief scout into his office, a former player named Clyde Sukeforth,[7] and told him that he intended to sign and bring to the majors a Black baseball player. He told Sukeforth that he didn’t yet know who the player was, or where he was, but that he was going to do it, and he needed Clyde’s help to find the man he needed. On hearing Rickey’s plan, Sukeforth was somewhat incredulous. After all, there hadn’t been a Black player in Major League Baseball for 61 years. But the scout also knew his boss, and realizing that he was serious in his intention, became his right-hand man in the search.

The hunt Rickey conducted for the player he needed was thorough, embracing not only the Negro Leagues, but Latin American countries where Blacks played, such as Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico and Venezuela. He camouflaged his search by floating the story that he was planning to form a new Negro League, to be called the United States League, comprised of all Black teams for the purpose of eventually integrating them into MLB. (The new league’s Brooklyn franchise would be called the “Brown Dodgers.”) Since Rickey’s announced plan presented no immediate threat to the color barrier, most owners and players figured it to be nothing more than a public relations move; one never coming to pass and ultimately forgotten. The ruse succeeded in obscuring Rickey’s true plan, preventing racist blowback until he had located his player and was ready to announce his intentions.

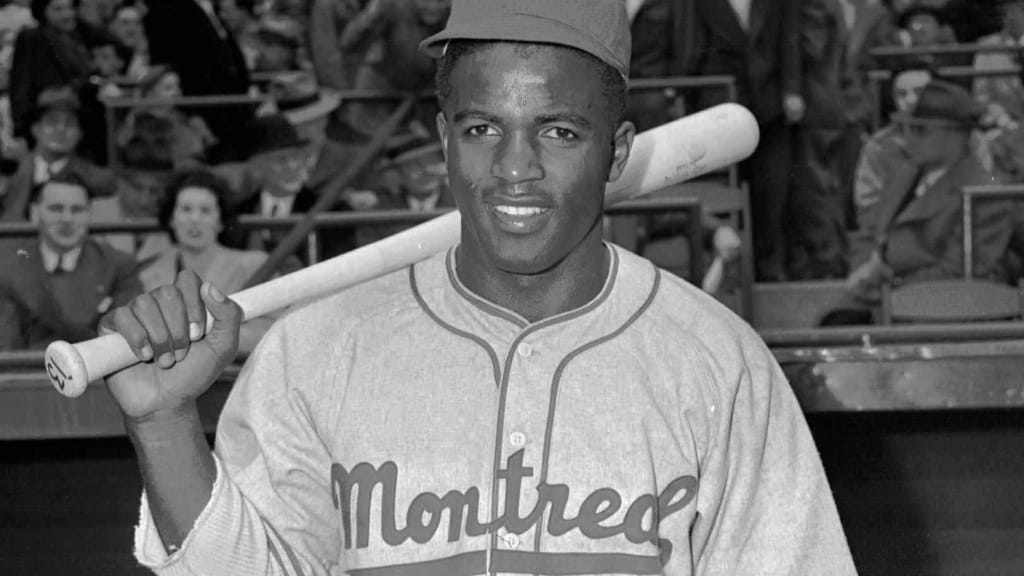

Months of search later, Rickey felt he had located his most promising prospect, a 26-year old shortstop playing for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro Leagues named Jackie Robinson. And so, in August of 1945, with the Monarchs playing in Chicago, Rickey dispatched Sukeforth to contact Robinson and convince him to come to Brooklyn for a meeting. The scout succeeded in the task, and a day or so later Jackie and Rickey met for the first time in the Brooklyn GM’s office. At the meeting Rickey asked Robinson if he knew why he asked him to come to New York. Robinson answered, saying Sukeforth told him it was to discuss signing with the new “Brooklyn Brown Dodgers” club. “That’s what he was supposed to tell you,” Rickey responded. “The truth is you’re not a candidate for the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers. I sent for you because I’m interested in you as a candidate for the Brooklyn National League Club. I think you can play in the major leagues. How do you feel about it?”

Besides being speechless, Jackie’s response to Rickey’s disclosure was emotional, a mixture of apprehension, excitement, and incredulity. Almost immediately the Brooklyn GM followed up by asking Robinson if he thought he could play for the Brooklyn AAA team, the Montreal Royals. Knowing that Montreal was just one step removed from the big time, and that if he made good there his door would be open to the majors, Jackie was finally able to command his wits sufficiently to say, “Yes!”

Rickey then regarded Robinson sternly, pointed his finger at him, and said, “I know you’re a good ballplayer. What I don’t know is whether you have the guts.”

At that point Robinson began to feel that Rickey’s suggestion was too good to be true. Black ballplayers were all too familiar with promises of future equity, parity and integration, only to have them end up as links on the chain of racial hypocrisy. Rickey’s words, he thought, were looking like another one of those. Then the GM leaned forward in his chair and explained himself further. He told Robinson that he wasn’t just another athlete being hired by a baseball club; that they were now playing for big stakes. That was the reason the search had been so extensive. When the candidates were narrowed down to Robinson and a couple of others, Rickey’s investigation of him intensified. He looked into the player’s home life, his habits, his reputation, and his character. From this, Rickey explained, he had discovered that Robinson had acquired a negative reputation as a race agitator while in college at UCLA. On reviewing the claims further, however, the GM had concluded that if the circumstances had been reversed, and Robinson was white, he would have been labeled as “competitive,” and a “contender,” instead of “agitator.” Dismissing the innuendo, Rickey had then gone ahead and invited Robinson to Brooklyn.

What the GM said next captivated Robinson. He explained that in going ahead with this plan they could not fight their way through it, that they would have no army; that virtually no one would be on their side—no umpires or owners, and very few journalists. Most fans, he said, would be against them at the start, and he made the point that, “We can only win if we can convince the world that I’m doing this because you’re a great ballplayer and a fine gentleman.” He followed that up by repeating the question to the player, “Have you got the guts to play the game no matter what happens?”

“I think I can play the game, Mr. Rickey.” Jackie responded.

Without missing a beat Branch Rickey then launched into scenario after scenario describing the types of things Jackie would likely encounter, and have to withstand, were he to take on the proposed challenge. Beanballs would be thrown at him, and names and foul language directed at him; even physical violence. “They’ll taunt and goad you,” Rickey said. “They’ll do anything to make you react. They’ll try to start a race riot in the ball park. This is the way to prove to the public that a Negro should not be allowed in the major league. This is the way to frighten the fans and make them afraid to attend the games.”

The GM then went on to graphically describe another situation. Suppose Jackie is playing shortstop during a game, and an opposing player is trying to steal second base. Robinson would need to cover second, and while readying himself to receive the catcher’s throw the runner begins his slide, feet first, elevating his spikes in a deliberate attempt to gash Jackie’s leg. He succeeds in laying open Robinson’s calf, and as blood starts seeping through Jackie’s uniform, the runner starts laughing at him. “How do you like that, nigger boy?” he sneers.

in such a situation, Rickey wanted to know, could Robinson turn the other cheek?

Taken aback, Robinson regarded Branch Rickey with a suspicious eye. Here was this white man, seemingly asking him to surrender what Jackie felt was his most precious possession—his dignity; something too often demanded of Blacks by white people. Was he serious?

“Mr. Rickey,” Jackie responded, “are you looking for a Negro who is afraid to fight back?”

“Robinson,” Rickey said vehemently, “I’m looking for a player with guts enough not fight back.”

Jackie reflected on what Rickey was asking him to do. He wondered, in situations such as those presented by the Brooklyn GM, could he turn the other cheek? He didn’t see how he could, but he realized that he would need to, and not just for himself. The hopes of so many would be riding on him; his family, his future wife, generations of future Black ballplayers and Black people in general, who had endured racism their whole lives; even Branch Rickey and other white people, who found the existing conditions intolerable and were trying to bring about change. In the end Jackie realized that he needed to do it for all of them, and so he agreed to sign the contract offered by Branch Rickey, to play baseball for Brooklyn’s AAA Montreal Royals farm team for the 1946 season. If he made good there, he would be elevated to the Dodgers to start the 1947 season.

About two months later, on October 23rd, 1945, Jackie officially signed his Montreal contract, and Rickey’s plan was announced to the world. As the GM had predicted, though some reporters encouraged the move, many were critical of the plan, making numerous negative comments. Former and current players, such as Rogers Hornsby and Bob Feller,[8] predicted that Jackie could never make it in the majors, while some of the racist owners suddenly developed a huge concern for the future of the Negro Leagues, claiming that Rickey’s plan would open the door to destroying the Black ball clubs. Despite the negativity, Robinson and Rickey were committed. As they forged ahead with their plan, for them there would be no turning back.

Robinson’s 1946 season with the Royals left little doubt that he had what it took to make it in the big leagues. He led Montreal to the International League title while also leading the league in hitting (.349), walks (92) and runs scored (113). Following the regular season, Montreal went on to win the “little” world series, a playoff between four of the top minor leagues. To do so the Royals had to defeat the Louisville Colonels of the American Association in the championship series, an experience that gave Jackie a taste of what he would face in terms of hostility when he hit the majors. As segregationist as any town in the deep south, Louisville hosted the first 3 games of the series and tested Jackie’s ability to withstand racial vitriol more than any town he’d played in so far. Torrents of verbal abuse in the form of boos and racial epithets cascaded down from the stands on each of his at bats and plays in the field. Making things worse, Jackie was in an extended slump through all 3 games, garnering just one hit in 11 at bats, as Montreal lost 2 of the first 3. On leaving Louisville and heading back to Canada for the rest of the series, things weren’t looking up for the Royals, or for Jackie Robinson. As it turned out, returning home to Montreal was exactly what Jackie and the team needed.

From the beginning of his time there, the people and fans of Montreal had embraced Jackie, taking him and his new wife, Rachel, into their hearts. None of the blatant racism in the U.S. seemed to exist in Canada. When the Robinsons moved to Montreal for the season, renting an apartment in the French-Canadian quarter, they were readily accepted by their neighbors; the little kids especially, who followed Jackie adoringly everywhere he went as he walked around the neighborhood. Now, on returning for the last 4 games of the “little” world series, the Montreal fans let the Colonels know exactly what they thought about the abuse Robinson had been subjected to in Louisville. From the second the Colonels players took the field for the first game in Canada, they were roundly booed by the fans, who kept it up through the rest of the series. While Jackie didn’t necessarily endorse the retribution, the support of the fans warmed his heart. Coincidentally, his bat came alive as he hit .400 for the rest of the series and scored the winning run in the final game.

With the last out, the ecstatic Montreal fans flooded onto the field, crowding around the players, slapping them on the back and hugging them, especially Jackie, who they elevated to their shoulders and carried around the field. After Robinson had showered and dressed he came out of the clubhouse to find thousands of fans still there applauding. As he hurried to catch a ride, the enamored fans rushed after him, a scene later described by sportswriter Sam Martin: “It was probably the only day in history that a Black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on its mind.”

Robinson’s 1946 baseball season in Montreal demonstrated conclusively that, from a skills standpoint, he was ready to make the jump to the majors. But in terms of the struggle against racism, a battle that’s won a mind at a time, he accomplished so much more. Exemplifying this is the story of Jackie’s manager at Montreal, a man named Clay Hopper.[9] Born in the deep south, Hopper was raised in the racist culture of Jim Crow, and carried those notions with him into his baseball career. His racist attitudes spilled over early in Jackie’s ’46 season when Branch Rickey and Hopper were standing together watching the team work out. As they watched, Jackie made an especially spectacular play, which Rickey, in a comment to Hopper, called “superhuman.”

Surprised, Hopper then asked Rickey, “Do you really think a nigger is a human being?”

Though the Brooklyn GM was enraged by Hopper’s comment, he did not respond to it. Much later he explained to Robinson why: “I saw that this Mississippi-born man was sincere,” Rickey said, “that he meant what he said; that his attitude of regarding the Negro as subhuman was part of his heritage; that here was a man who had practically nursed race prejudice at his mother’s breast. So I decided to ignore the question.”

Illustrating the change of which people are capable, even those as immersed in racism as the Montreal manager, is an incident that happened in the joy of the Royals clubhouse directly following the team’s little world series championship. As he was preparing to leave Montreal and return to his Mississippi home for the winter, Hopper approached Jackie and held out his hand. “You’re a great ballplayer and a fine gentleman,” he said. “It’s been wonderful having you on the team.”

For spring training prior to the 1947 season, Rickey asked Robinson to report to the Montreal Royals camp in Havana, Cuba. With his great 1946 season for the Royals already demonstrating the kind of player he was, this was a bit confusing to Jackie; but he trusted Rickey, and was willing to allow things to play out as the GM determined. As Jackie soon discovered, the Dodgers would also be training in Havana, so at least if Rickey opted to bring him to the big club it would be an easy trip. On arriving in Havana Jackie was immediately confronted with another concern: he was told that he needed to learn to play first base, a position he’d never played. To Robinson, who had always played 2nd base or shortstop, the position change was unwelcome, as he thought it might delay his getting to the majors. The way it was explained to him, however, was that the Dodgers were solid at shortstop and second base, where star players Pee Wee Reese[10] and Eddie Stanky[11] held sway, but that they needed help at first base. So, with the position change looking like his fastest route to the Dodgers, Jackie decided to make the most it.

Finding out that Jackie’s position had been shifted from shortstop to first base ignited fear within the Dodgers that Rickey really did intend to bring him to the big club. With Reese and Stanky at short and second respectively, and first base a relative weakness, Robinson training for the position was threatening to Dodgers players with racist inclinations. Consequently, 4 such players, Dixie Walker, Hugh Casey, Carl Furillo and Bobby Bragan, started a petition amongst the players stating that if Jackie were brought to the Dodgers they wouldn’t play. The story goes that when Dodgers manager Leo Durocher[12] found out about the petition he called a players only meeting in the middle of the night and read his team the riot act. While in his bathrobe, he told his players that as far as he was concerned they could “wipe their asses” with their petition, and that he didn’t care if Robinson was “green or yellow or pink,” that he was coming, would help the Dodgers win, and the players needed to set their minds to it. When Rickey found out about the petition he called the ring leaders into his office one by one and told them each that they could either accept a Black player on the team, or they could quit. Between the actions of Durocher and the GM, the petition effort withered and died before gaining any real traction.

Early in that ’47 spring training Rickey pulled Robinson aside and told him that he shouldn’t rest on what he’d accomplished in Montreal the year before; that the true test would be if he could handle major league pitching. With 7 Montreal vs. Brooklyn practice games scheduled that spring, he told Jackie that he wanted him to “be a whirling demon against the Dodgers.” He told the player he wanted him to concentrate, to hit the ball, and “to get on base by any means necessary.” He stressed to Robinson that he wanted him to “run wild, to steal the pants off them, to be the most conspicuous player on the field—but conspicuous only because of the kind of baseball you’re playing.” Performing like that, Rickey said, would help the Dodgers players see the value of bringing him to the big club; and when the reporters wrote of his play in the sports pages, demand would develop from the fans to see Jackie play at Ebbets Field.

With the general manager’s strategy now clear, Robinson understood why he was ordered to start spring training with Montreal. Rickey needed him to make a splash AGAINST Dodgers pitching, as if he did the Dodgers players would want him on the team, leaving the GM no choice BUT to elevate Jackie to the big club. The plan was brilliant—if it worked—and Robinson did his best to ensure it would. Across those 7 games against the Dodgers he hit for an astounding .625 batting average, while stealing a ridiculous 7 bases. His production exceeded anything Rickey could have hoped for, but did not have the desired effect of causing the Dodgers players to demand that Jackie be made a teammate, such were the encysted racist considerations of some of them.

Plan B was then resorted to, with Rickey getting Leo Durocher to use the sportswriters as a tool. The idea was to have Durocher tell the reporters that with a good first baseman the Dodgers would have a shot at the pennant, and that to him Jackie was that man. The articles written by the reporters would then create fan demand to bring Robinson to the Dodgers. Before they could implement the plan, however, disaster struck when MLB commissioner Happy Chandler suspended Durocher from baseball for a year due to “conduct detrimental to the game.” Apparently Leo, who was known to consort with gamblers, Hollywood types and the occasional gangster, had married the actress Larraine Day on the heels of her divorce from a man named Ray Hendricks. The divorce was contested by Hendricks, who felt Durocher had stolen his wife. On granting the divorce the judge strongly suggested that Day not re-marry for at least a year, only to have Leo and the actress tie the knot in Mexico a couple days later. The resulting flap made the news, which caused the Catholic Youth Organization to threaten a boycott of baseball. Chandler responded by suspending Durocher.

All of which left Branch Rickey with two problems: first, he still needed to get Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers; second, he now had a team with no manager. With spring training winding down and opening day right around the corner, Rickey needed to move fast on both counts. The manager issue he temporarily handled by having Clyde Sukeforth take the helm for the last week of spring training, an assignment that extended through the first two games of the season. As for Jackie, Durocher’s suspension had generated a lot of negative press for the team, and the GM, realizing that Robinson making the Brooklyn Dodgers would supersede everything else news wise, knew the time had come to make the move. Thus, on April 9th, six days before the start of the 1947 season, the sports writers covering the team all received a press release from the Dodgers comprised of a single line, a fact belying the release’s importance:

“Brooklyn announces the purchase of the contract of Jack Roosevelt Robinson from Montreal. Branch Rickey”

With that announcement, the 28-year old Jackie Robinson became a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers; the first Black man on a major league roster in 64 years. Six days later, on April 15th, 1947, he took the field at first base for the Dodgers to start the season. The Major League Baseball color barrier, held so rigidly in place for so long, had at last been broken.

History shows that in Jackie Robinson, Branch Rickey picked the right man for his “Nobel Experiment”[13] in breaking the major league color barrier. Though Robinson started off slowly in that 1947 season, he ended up hitting .297, with a .383 on base percentage and 125 runs scored while stealing 29 bases; production that earned him the National League Rookie of the Year award. As Rickey knew they would, Jackie’s baseball talents and skills translated beautifully to the major leagues. It was Robinson’s other qualities, however, the ones that allowed him to withstand the racist abuse he endured in that initial season, without fighting back, that illustrated the brilliance of Rickey’s choice.

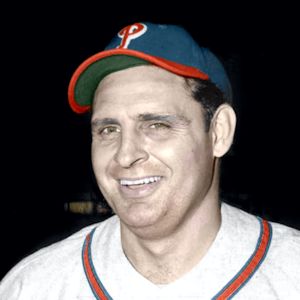

Though the GM’s decision proved to be sound, for Jackie, living up to his promise tested him to the very core of his being. In his autobiography, “I Never Had It Made,” Robinson discusses one of the now famous incidents that took place early in the season, before even the Dodgers players had fully accepted the Black player now on their team. As Jackie relates it, the Philadelphia Phillies had come to Ebbets Field for a 3-game series in late April. From Robinson’s first plate appearance in the first game of the series, the Phillies let him have it: “I could scarcely believe my ears,” Jackie states in his book, “…hate poured forth from the Phillies dugout.”

“‘Hey, nigger, why don’t you go back to the cotton field where you belong?’“

“’They’re waiting for you in the jungles, black boy!’”

“’Hey, snowflake, which one of those white boys’ wives are you dating tonight?’”

“’We don’t want you here, nigger.’”

“’Go back to the bushes!’”

Orchestrating the racist Phillies onslaught was the team’s manager, a Southerner named Ben Chapman.[14] Known in baseball for baiting opposing players with ethnic slurs, like “kike” for Jewish players, or “wop” for Italian players, Chapman would later try to claim he was treating Robinson as he did other opponents. What eye and ear witnesses perceived, including fellow Dodgers players and even some of the Phillies players, indicates otherwise, however. Chapman’s effort clearly was to degrade Robinson, invalidating him to the point he would have to strike back, thus demonstrating he could not handle the major leagues; and in that the Phillies manager nearly succeeded. Though Jackie tried to just play ball and ignore the insults, as the game went on he acknowledges that the constant abuse nearly broke him. In his book, he shares his internal dialog at the time: “What did the Phillies want from me?” he reflects. “What, indeed, did Mr. Rickey expect of me? I was, after all, a human being. What was I doing here turning the other cheek as though I weren’t a man?” Jackie then states that for one “rage-crazed minute” he teetered on the precipice of throwing away everything he and Branch Rickey had worked for. He relates that he wanted to, “…throw down my bat, stride over to that Phillies dugout, grab one of those white sons of bitches and smash his teeth in with my despised black fist.”

Fortunately for Branch Rickey, for baseball, for posterity, and for himself, Robinson was able to step back from the abyss.

The Dodgers eventually won the first game of the Phillies series when Robinson led off the bottom of the seventh with a single, stole second, took 3rd on a bad throw, and then scored what would be the game’s only run on another Dodger single. Despite the loss, the Phillies manager and players kept up the abuse against Robinson for the remaining two games. By the 3rd game, seeing what their teammate was having to go through, a transformation had begun to occur among the Dodgers players, and they began to unite behind Jackie. One of them, second baseman Eddie Stanky, become so outraged at the Phillies that he started to yell back at them. “Listen you yellow-bellied cowards,” Stanky hollered, “why don’t you yell at somebody who can answer back?”

Remembering what Rickey had told him, that if he could win the respect of the Dodgers players and get them solidly behind him, then their battle would be won, Jackie began to feel better. There would be more rough days ahead, more racism to be endured, but for Brooklyn, and for baseball, a corner had been turned.

Epilog

The success of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey in shattering the Major League Baseball color barrier changed forever not only the sport, but our nation itself. Keep in mind that in 1947 the courageous act of Rosa Parks[15] in refusing to sit in the back of a Montgomery, Alabama bus after a hard day at work, was still years into the future. Martin Luther King, when Jackie took his first at bat as a Brooklyn Dodger, was a junior at Morehouse College in Atlanta. At the time, no one had ever heard of him. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, widely recognized as launching the modern civil rights movement and which catapulted both King and Parks to national prominence in 1955, was presaged by what Rickey and Robinson took on and accomplished in 1947, 8 years before.

As for Major League Baseball, once Jackie took that first step it took only a few weeks before more Black players began to arrive in the majors. In the summer of ’47 the Cleveland Indians brought up a Black outfielder named Larry Doby, and the St. Louis Browns soon followed with the additions of Hank Thompson and Willie Brown, who became the first Black major league teammates. In 1948 the Dodgers added All Star catcher Roy Campanella, and in ’49 the Indians signed the legendary Negro League pitcher, Satchel Paige. That same season the Dodgers brought up future All Star pitcher Don Newcombe, the New York Giants did the same with another future All Star, Monte Irvin, and the Indians elevated to their team Minnie Miñoso, otherwise known as the “Cuban Comet” because of his great speed.

As the 1940s merged into the 1950s, largely due to the influx of so many talented Black players, Major League Baseball boomed with one of the most amazing decades in its storied history. Players like Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks and Frank Robinson, 5-tool players [16]all, launched their major league careers and began the process of re-writing baseball’s record books with their amazing production on the field. In the National League, between 1949, when Jackie Robinson became the first Black to win the Most Valuable Player award in baseball’s modern era, and 1962, Black players won the MVP in 11 of the 14 seasons. It was an amazing time, causing the more aware fans and pundits to speculate: What have we been missing for the previous six plus decades?

And in that question we see at once the tragedy, as well as the hope, of the United States of America. The racism that has manifested in our nation since its founding, through the generations of slavery, the Klan and Jim Crow, on up to its less overt, more modern, but no less destructive forms, has exacted a heavy toll. Friendships never formed, talents never realized, skills never developed, intellects never educated, all because of prejudice, have denied much to our nation, both culturally and economically. Adding to this is the hypocrisy inherent in a country founded on the principle, “All men are created equal…” These things and more comprise the “tragedy” of our country.

But if those describe the “tragedy” of our nation, what, then, of the “hope”? Much is being said these days about the United States being intrinsically and systemically racist, leading to the belief that the only way to deal with it is to tear down the elements of society and culture thought to be contributing to and creating that racism. I hold a different view, however. The real story of the United States across the last 250 years, I believe, is told by its own internal struggle to, as Martin Luther King said, “live out the true meaning of its creed…” [17] The struggle is far from over, but where real progress is being made it’s NOT taking place through cultural destruction or even legislation, though laws do play a role. But, since no law ever changed a person’s mind, the real progress in the battle against racism and FOR human rights can only take place one mind at a time. Cultures, groups, societies, nations, even civilizations, are composed of individual people; thus, a mind at a time is about as fast as real change can happen.

Therein lies the brilliance of what Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey accomplished in breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball–with what they did they changed many minds.

And, as far as Human Rights is concerned, therein lies the hope for the future of our nation and the world.

[1] Moses Fleetwood Walker (October 7, 1856 – May 11, 1924) was an American professional baseball catcher who, historically, is credited with being the first Black man to play in Major League Baseball (MLB). A native of Mount Pleasant, Ohio, and a star athlete at Oberlin College as well as the University of Michigan, Walker played for semi-professional and minor league baseball clubs before joining the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association (AA) for the 1884 season. Though research by the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) indicates a player named William Edward White was the first African-American baseball player in the major leagues, Walker, unlike White (who passed as a white man and self-identified as such), was the first to be open about his Black heritage, and to face the racial bigotry so prevalent in the late 19th century United States.

[2] Kennesaw Mountain Landis (November 20, 1866 – November 25, 1944) was an American jurist who served as a US federal judge from 1905 to 1922 and the first Commissioner of baseball from 1920 until his death. He is remembered for his handling of the famous “Black Sox” scandal, in which he expelled eight members of the Chicago White Sox from organized baseball for conspiring to lose the 1919 World Series and repeatedly refused their reinstatement requests. His firm actions and iron rule over baseball in the near quarter-century of his commissionership are generally credited with restoring public confidence in the game. He is also remembered, however, for his stalwart opposition to allowing Black players into Major League Baseball.

[3] The Black Sox Scandal was a Major League Baseball game-fixing scandal in which eight members of the Chicago White Sox were accused of throwing the 1919 World Series against the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for money from a gambling syndicate led by Arnold Rothstein. As a response, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis was appointed to be the first Commissioner of Baseball, and given absolute control over the sport to restore its integrity. Despite acquittals in a public trial in 1921, Judge Landis permanently banned all eight of the players involved. The punishment was eventually defined by the Baseball Hall of Fame to include banishment from consideration for the Hall. Despite requests for reinstatement in the decades that followed (particularly in the case of Shoeless Joe Jackson), the ban remained.

[4] Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler Sr. (July 14, 1898 – June 15, 1991) was an American politician from Kentucky. He represented Kentucky in the U.S. Senate and served as its 44th and 49th governor. Aside from his political positions, he also served as the second Commissioner of Baseball from 1945 to 1951, and was thus on the post when Branch Rickey launched is plan to integrate MLB. He was inducted into the Baseball hall of Fame in 1982.

[5] Wendell Smith (1914-1972) is one of the unsung figures in the struggle for racial integration. As portrayed in the recent film “42”, Smith played a key role in the Jackie Robinson story but his effect on American life extended far beyond Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers. As a sportswriter he wrote thousands of columns between 1937 and 1972, was an ardent advocate for the integration of the game, and became the first African-American member of the Baseball Writers Association of America. Smith died in 1972 of pancreatic cancer, just one month after the passing of Robinson. He was 58 years old.

[6] Part of the impetus for the integration of Major League Baseball was driven by the increasing awareness of the hypocrisy made apparent by the fact that Black men had served and fought valiantly for the nation in World War II but could not enjoy the full benefits of the cause they fought for at home in the United States. Guadalcanal (1942-43) and Okinawa (1945) were two of the more famous battles fought against the Japanese in the Pacific theatre in the war.

[7]Clyde Leroy Sukeforth (1901-2000)nicknamed “Sukey”, was an American professional baseball catcher, coach, scout and manager. Though he was best known for helping Branch Rickey sign the first Black player in the modern era of Major League Baseball, Jackie Robinson, he had a long career in baseball as a player before that and as a scout and minor league manager after. Not as well-known is the fact that Sukeforth was also Robinson’s first Major League manager. Rickey assigned him to be the interim manager for the Dodgers at the start of the 1947 season after the regular Brooklyn manager, Leo Durocher, was suspended for 1 year by commissioner “Happy” Chandler for having an out of wedlock affair with Hollywood actress Laraine Day, which was causing a public relations flap for MLB. Sukeforth managed the Dodgers for the first 2 games of the ‘47 season, both victories.

[8] Rogers Hornsby Sr. (April 27, 1896 – January 5, 1963), nicknamed “The Rajah“, was an American baseball infielder, manager, and coach who played 23 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB). One of the greatest hitters ever, the Hall of Famer played for the St. Louis Cardinals (1915–1926, 1933), New York Giants (1927), Boston Braves (1928), Chicago Cubs (1929–1932), and St. Louis Browns (1933–1937). He was named the National League MVP twice, and was a member of one World Series championship team. Robert William Andrew (Bob) Feller (November 3, 1918 – December 15, 2010), nicknamed “The Heater from Van Meter“, “Bullet Bob“, and “Rapid Robert“, was an American baseball pitcher who played 18 seasons in Major League Baseball for the Cleveland Indians between 1936 and 1956. In a Hall of Fame career spanning 570 games, Feller pitched 3,827 innings and posted a win-loss record of 266–162, with 279 complete games, 44 shutouts, and a 3.25 ERA. His career 2,581 strikeouts were third all-time upon his retirement.

[9] Robert Clay Hopper (October 3, 1902 – April 17, 1976) was an American professional baseball player and manager in minor league baseball. Hopper played from 1926 through 1941 and continued managing through 1956. Managing the Montreal Royals of the International League in 1946, Hopper served as Jackie Robinson’s first manager in integrated baseball. Hopper was named manager of the year with the Royals in 1946 and with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League in 1953. He was inducted into the International League Hall of Fame in 2009.

[10] Harold Peter Henry “Pee Wee” Reese (July 23, 1918 – August 14, 1999) was an American professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball as a shortstop for the Brooklyn/LA Dodgers from 1940 to 1958. A ten-time All-Star, Reese contributed to seven National League championships for the Dodgers and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1984 Reese is also famous for his support of his teammate Jackie Robinson, the first Black player in the major leagues’ modern era, especially in Robinson’s difficult first years.

[11] Edward Raymond Stanky (born Stankiewicz[1] (September 3, 1915 – June 6, 1999) was an American professional baseball second baseman, shortstop, and manager. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Chicago Cubs, Brooklyn Dodgers, Boston Braves, New York Giants, and St. Louis Cardinals between 1943 and 1953. Stanky contributed to the breaking of the color barrier as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. Upon first meeting Jackie Robinson at spring training, Stanky told him he was not in favor of integrating baseball, and that he was unhappy that it was his own team doing it, but that despite his own personal feelings, Robinson was now his teammate, and Stanky promised he would have his back.

[12] Leo Ernest Durocher (July 27, 1905 – October 7, 1991), nicknamed Leo the Lip and Lippy, was an American professional baseball player, manager and coach. He played in Major League Baseball as an infielder. Upon his retirement, he ranked fifth all-time among managers with 2,008 career victories, second only to John McGraw in National League history. Durocher still ranks tenth in career wins by a manager. A controversial and outspoken character, Durocher had a stormy career dogged by clashes with authority, the baseball commissioner, the press, and umpires; his 95 career ejections as a manager trailed only McGraw when he retired, and still ranks fourth on the all-time list. Durocher was posthumously elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1994.

[13] Branch Rickey’s plan for bringing a Black Player to MLB and breaking the baseball color barrier is often termed “Rickey’s Nobel Experiment.”

[14] William Benjamin Chapman (December 25, 1908 – July 7, 1993) was an American outfielder and manager in Major League Baseball who played for several teams. He began his career with the New York Yankees, playing his first seven seasons there. During the period from 1926 to 1943, Chapman had more stolen bases than any other player, leading the American League four times. After 12 seasons, during which he batted .302 and led the AL in assists and double plays twice each, he spent two years in the minor leagues and returned to the majors as a National League pitcher for three seasons, becoming player-manager of the Philadelphia Phillies, his final team. Chapman’s playing reputation was eclipsed by the role he played in 1947 as manager of the Phillies, antagonizing Jackie Robinson by shouting racist epithets and opposing his presence on a major league team on the basis of Robinson’s race with unsportsmanlike conduct that was an embarrassment for his team. He was fired the following season and never managed in the majors again.

[15] Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American activist in the civil rights movement best known for her pivotal role in the Montgomery bus boycott. The United States Congress has honored her as “the first lady of civil rights” and “the mother of the freedom movement”.On December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, Parks rejected the bus driver’s order to vacate a row of four seats in the “colored” section in favor of a white passenger, once the “white” section was filled. Parks was not the first person to resist bus segregation, but the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) believed that she was the best candidate for seeing through a court challenge after her arrest for civil disobedience in violating Alabama segregation laws, and she helped inspire the black community to boycott the Montgomery buses for over a year. Parks’ act of defiance and the Montgomery bus boycott became important symbols of the movement. She became an international icon of resistance to racial segregation and organized and collaborated with civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr.

[16] The five tools of baseball are speed, and the ability to catch the ball, throw the ball, hit the ball and hit for power. Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks were all 5-tool players.

[17] In his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on 28 August, 1963, in Washington DC, Martin Luther King spoke these words: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’ “

One Response

Good write-up, I’m normal visitor of one’s blog, maintain up the excellent operate, and It’s going to be a regular visitor for a long time.