Note: I am a firm believer in knowing and understanding how we got to be where we are in this country. Our true history is important, and from it there are important lessons to learn. This is especially the case, I think, with regard to the situation with racism in this nation. It’s an old problem here, with a lot of water under the bridge. Our hope, I believe, lies in the truths enshrined in our founding documents. We need to look to them now more than ever, and learn from the mistakes of the past. Please read on…MA

______________________________________

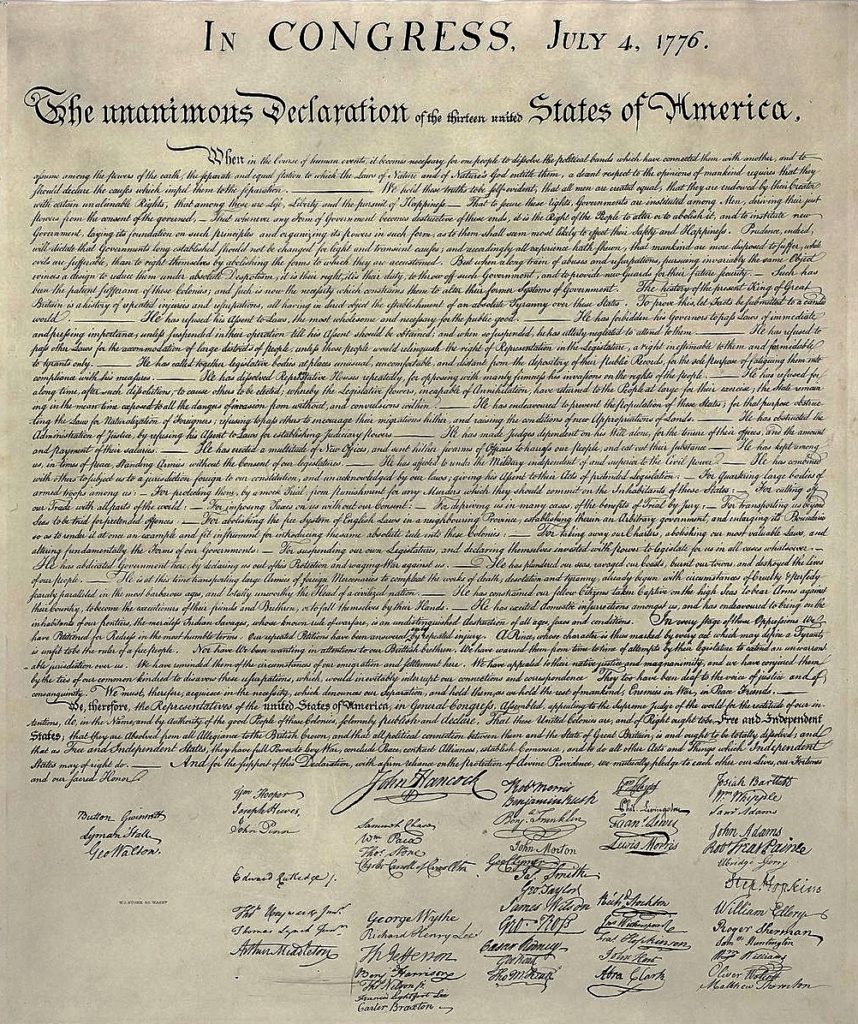

In his novel “Requiem for a Nun” award winning American writer William Faulkner[1] crafted one of his more famous lines when he wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.” The line has been often borrowed by others for various talks or writings, and used in different contexts; but to Faulkner, who was born in Mississippi and lived most of his life in the South, his creation referred to the way Southerners seemed never able to escape their past, and so remained haunted by it. Of course, a huge part of that Southern “haunting past” is its history of “Jim Crow”[2] racism and outright slavery of Black people, and I’m sure that Faulkner at least partially had that in mind when he wrote that line. Nevertheless, with what we observe happening today with the Black Lives Matter protests across our nation, it’s obvious that being unable to escape the past isn’t just a Southern problem, but one affecting all Americans, whether White or Black or North or South. To boot, the incredible irony of our predicament is that this is all happening in a country founded on the premise, “that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Those inspiring lines, written by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, form the moral core of the document and, indeed, the nation that document founded. With a simple adherence to that founding principle there would have been no slavery, no Civil War or subsequent Reconstruction; no “Jim Crow”; no Civil Rights movement; no Black Power movement, and no Black Lives Matter movement. They simply would not have been necessary. So, why has it been so tough? Why is it that today we are still “haunted” by our past, as described by Faulkner with his famous line?

To understand the answer to this question one must come to terms with this simple fact: many of our more famous Founders, men like Jefferson, Washington and Madison, were, in truth, racists. All three of these men owned slaves, as did many of their associates, amounting to nearly half of the original signers of the Declaration. Did these men really believe that “all men were created equal”? Or, did they, and Jefferson in particular, interpret the word “men” in the Declaration usage to mean only “White men”? I am afraid, based on the evidence, that it’s reasonable to conclude that they meant the latter.

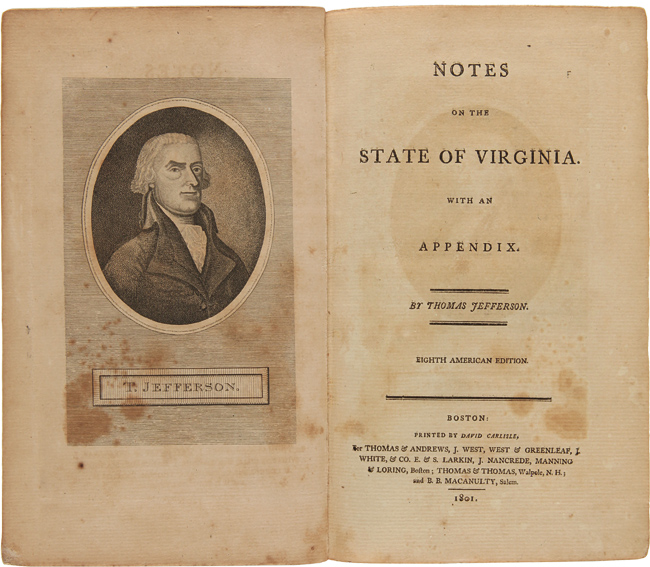

With a deeper look into Jefferson’s writings, however, it becomes obvious that he was deeply conflicted on the subject. In the only full length book written and published by him within his own lifetime, entitled “Notes on the State of Virginia,” he recorded some of his thoughts about Blacks and slavery; and when you read his words the conflict in his mind becomes apparent. On the one hand, in his descriptions of Blacks and slaves he makes several clearly racist comments; to the point where, if you are a Jefferson admirer, as I am, it’s very difficult to emerge from the read with your admiration intact.

On the other hand, a little later in the same book, he wrote the following:

by Thomas Jefferson

“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. Our children see this, and learn to imitate it; for man is an imitative animal. This quality is the germ of all education in him. From his cradle to his grave he is learning to do what he sees others do. If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present. But, generally it is not sufficient. The parent storms, the child looks on, catches the lineaments[3] of wrath, puts on the same airs in the circle of smaller slaves, gives a loose to the worst of passions, and thus nursed, educated, and daily exercised in tyranny, cannot but be stamped by it with odious pecularities. The man must be a prodigy who can retain his manners and morals undepraved by such circumstances. And with what execration[4] should the statesman be loaded, who, permitting one half the citizens thus to trample on the rights of the other, transforms those into despots, and these into enemies, destroys the morals of the one part, and the amor patriae[5] of the other. For if a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is born to live and labour for another; in which he must lock up the faculties of his nature, contribute as far as depends on his individual endeavours to the evanishment[6] of the human race, or entail his own miserable condition on the endless generations proceeding from him. With the morals of the people, their industry also is destroyed. For in a warm climate, no man will labour for himself who can make another labour for him. This is so true, that of the proprietors of slaves a very small proportion indeed are ever seen to labour. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever: that considering numbers, nature and natural means only, a revolution of the wheel of fortune, an exchange of situation is among possible events: that it may become probable by supernatural interference! The almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest…”

Based on his words just quoted, one can sense Jefferson’s dilemma. He knew that slavery was immoral, obviously, and he feared for the future because of the sin of it. It’s as if the immortal and more senior truth he penned in the Declaration, about all men being created equal, was at war in his mind with the realities of his everyday life, and his justifications for that life. Understanding this, we today can see Jefferson’s great failing: he had the awareness of the sin manifested by slavery and racism, but lacked the moral courage to confront and do something about it. This can be seen in the following words from Jefferson, written a little later in his book:

“But it is impossible to be temperate and to pursue this subject through the various considerations of policy, of morals, of history natural and civil. We must be contented to hope they will force their way into every one’s mind. I think a change already perceptible, since the origin of the present revolution. The spirit of the master is abating, that of the slave rising from the dust, his condition mollifying[7], the way I hope preparing, under the auspices of heaven, for a total emancipation, and that this is disposed, in the order of events, to be with the consent of the masters, rather than by their extirpation.[8]”

In other words, Jefferson was unwilling to confront the inherent evil of slavery head on and, per his own words, was instead content to delay the problem’s resolution until such time as its “various considerations of policy, of morals…” and so on, “forced their way into every one’s mind.”

Well, that’s disappointing to be sure, but lest we judge the Virginian Founding Father too harshly we must keep in mind the effect of his famous “all men are created equal” line in the Declaration. Jefferson wrote that line in 1776; he completed the first version of his “Notes on the State of Virginia” in 1781, just five years later and before the American Revolution had even concluded. (There would be several revisions of the book by Jefferson before it was finally published, first in France in 1785 as a limited edition, and then as a more commercial edition in London in 1787.) Whether he meant just “White men” when he wrote that line in 1776, by the early to mid 1780s Jefferson was in a state of moral compunction about Blacks and slavery. Personally, I think the truth of his “all men are created equal” statement was eating away at him.

But, it wasn’t just Jefferson who, by that simple yet profound line in the Declaration, was being compelled to re-evaluate the slavery and race issue in the fledgling United States. Following the Revolution slave owners In Jefferson’s home state of Virginia began freeing their slaves in ever increasing numbers. In 1782 there were just 1800 free Blacks in Virginia; but by 1810 there were over 30,000. Across that same time many northern states abolished slavery altogether, while the percentage of the total population of Blacks in bondage in the North fell to around 25 percent. In the upper southern states (Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina), by 1810 the number of freed Blacks amounted to 10 percent of the overall Black population. It’s as if the hypocrisy of founding a nation conceived on the proposition that “all men are created equal,” yet which still abided slavery, was becoming intolerable to many people, including some slave owners.

ca. mid 19th century

A consequence of the growing number of free Blacks in the United States in the early 1800s was the development of proposals and initiatives to assist them to leave the country to form colonies of their own in other parts of the world. Jefferson himself supported these ideas, feeling that, as stated in his book: “For if a slave can have a country in this world, it must be any other in preference to that in which he is born to live and labour for another…” In other words, Jefferson, and many other Southern slave holders, felt that the formerly enslaved Blacks would be so angry at the treatment they’d received from their prior masters that it would behoove both races if the Blacks would simply go and live elsewhere. Also, particularly for slave owners in the deep South, where they were far more dependent on their slaves and far less inclined to free them, there was a major concern over the possibility of slave rebellion. By the early 1800s there had already been a number of minor rebellions in the United States; and all slave owners, and many slaves for that matter, knew of the successful slave revolt in the French colony of Saint-Domingue that started in 1791 and eventually achieved independence for that colony in 1804, thus creating the country of Haiti.[9] Southern slave holders lived in fear of such an event in the South, and felt that the presence of so many free Blacks in the United States served as inspiration to their slaves to fight for their freedom too. Ultimately this led to the strange circumstance of some southern slave holders allying themselves with some northern abolitionists and influential businessmen to form a coalition they called the American Colonization Society (ACS), the purpose of which was to assist American free Blacks to colonize other parts of the world.

The first effort of the ACS at forming a free Black colony took place after the United States passed the Slave Trade Act in 1819. At the time James Monroe, who was a Jefferson protégé, was President; and like his mentor he favored the idea of American free Blacks starting their own colonies. As part of the Slave Trade Act, which made the trafficking of Africans for the slave trade illegal, (something Jefferson had been advocating for since he penned the Declaration) money was allocated by the U.S. government to send some of its Navy ships to the west coast of Africa to apprehend the slave traders and return their human cargo to their homelands. To accomplish this the Navy needed a secure port on the west coast of Africa, which it didn’t have. That is when the ACS stepped forward and petitioned the U.S. government for assistance in creating a free Black colony in Africa. In response Monroe created what was called the African Agency, and charged it with the task of arranging transport and supplies for American free Blacks to travel to and found a colony in West Africa on land to be procured by the ACS. The colony would then provide the Navy with the secure port it needed to return the Africans taken from the slave traders.

West Africa

The effort of the African Colonization Society at establishing this American free Black colony in West Africa was not the first attempt at establishing such a colony, but from what I could determine it was the first effort that succeeded. The free Blacks ultimately named the colony they founded “Liberia” (derived from the word “liberty”) and they called their capitol city “Monrovia”, after the U.S. President who assisted in the colony’s creation. With the colony continuing to be sponsored by the ACS through its formative years, the free Blacks established a government and constitution based on the model of the United States and with ACS support continued to import more free Blacks from their former homeland. Across the next 20 years the colony grew and by the mid 1840s had developed itself enough to take the step of cutting the ACS umbilical cord and declaring its independence as a new country—thus, the West African nation of Liberia was born, which still exists today. [10]

Lest one think that the American free Blacks arrived in West Africa and easily integrated themselves into the indigenous African population there; the truth is that was far from the case. The land for their colony was basically stolen from the Africans already living there, and was defended by their superior firepower in the form of guns and cannon provided to the free Blacks by the ACS; circumstances which did not endear the colonists to the indigenous peoples. On top of this, the government and society established by the American free Blacks in Liberia was every bit as discriminatory toward the indigenous Africans as the American society had been to the free Blacks. Indigenous Africans were not allowed the basic freedoms that the American free Blacks in the colony enjoyed, and they were relegated to second class status as citizens. Ironically, the free Blacks had more in common culturally with the White dominated society in the U.S. than they did with the Africans, from whom by the mid 1840s they were generations removed. The decades of injustice that ensued in Liberia because of the free Blacks’ discriminatory rule ultimately resulted in a long, tragic and violent civil war in that nation that has only recently concluded.[11]

There is much we can learn from the experience of the free American Blacks and their efforts to create a new nation in Africa; as well as from what ultimately happened in Liberia as a result of the discriminatory policies and laws they employed. Once they embarked on the path of denying the natural rights of the indigenous Africans, it was only a matter of time until the scourge of civil war tore the country apart. At any time they could have completely altered their country’s future had they simply acknowledged the truth of Jefferson’s “all men are created equal” statement and worked to make it manifest in their own nation.

Document

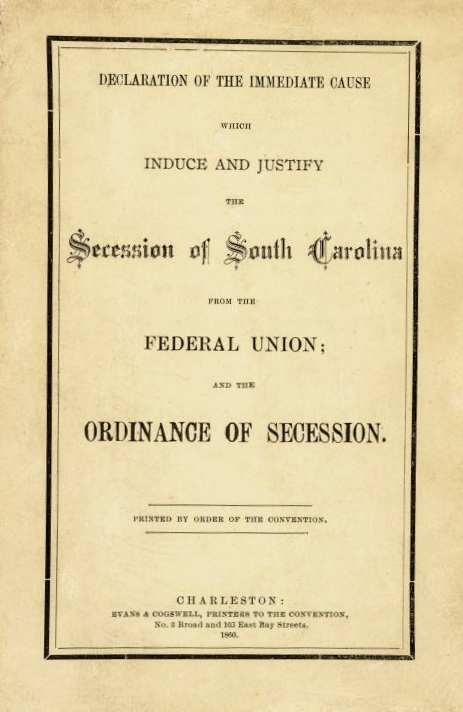

Of course, if there is an ultimate example of the price a nation must pay for engaging in and institutionalizing practices suppressive of the natural rights of some of its citizens, it has got to be the American Civil War. From the time Jefferson wrote the Declaration on through to the secession of the Southern States in 1861, a period of 85 years, the United States continued to countenance the practice of the most abject form of human rights violation—slavery. Across those 85 years, despite the development of a vibrant abolitionist movement in the North that made some inroads into the South, the U.S. Congress in the main continued to temporize on the subject with compromise after compromise, the effect of which was to simply allow the bondage of millions of Blacks in the South to continue. Compared to Jefferson’s magnificent words it was an intolerable condition: a blind man could see the hypocrisy of it. Finally, with the election of Abraham Lincoln as President in late 1860, things reached a breaking point. On December 24th, 1860, the state of South Carolina issued its Declaration of Secession, which stated its reasons for departing from the Union. There are historians and academicians who claim that slavery was not the prime reason for the Civil War. They cite such things as the rights of sovereign States, and that the right to withdraw from the Union is implied in the Constitution. While there may be some truth to what they say, in the main I beg to differ. The following is directly quoted from the South Carolina Declaration of Secession, and I believe it speaks volumes as to the actual cause of the Civil War:

“The General Government, as the common agent, passed laws to carry into effect these stipulations of the States. For many years these laws were executed. But an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the institution of slavery, has led to a disregard of their obligations, and the laws of the General Government have ceased to effect the objects of the Constitution. The States of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa, have enacted laws which either nullify the Acts of Congress or render useless any attempt to execute them. In many of these States the fugitive is discharged from service or labor claimed, and in none of them has the State Government complied with the stipulation made in the Constitution. The State of New Jersey, at an early day, passed a law in conformity with her constitutional obligation; but the current of anti-slavery feeling has led her more recently to enact laws which render inoperative the remedies provided by her own law and by the laws of Congress. In the State of New York even the right of transit for a slave has been denied by her tribunals; and the States of Ohio and Iowa have refused to surrender to justice fugitives charged with murder, and with inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia. Thus the constituted compact has been deliberately broken and disregarded by the non-slaveholding States, and the consequence follows that South Carolina is released from her obligation.”

The “stipulations” being referred to in the first line of this quoted passage refer to a clause in Article IV, Section II of the Constitution which states:

“No person held to service in one State, under the laws thereof, escaping to another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on the claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.”

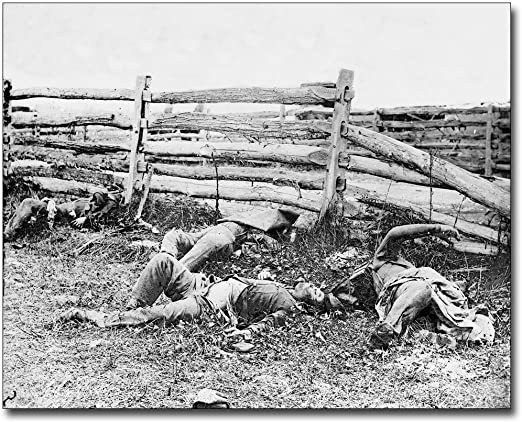

As the Southerners interpreted it, that clause meant that any slave who escaped bondage and fled to any other state, lawfully needed to be returned to his rightful owner in that slave’s home state. The South Carolina Secession Declaration then states that the General Government passed laws to carry into effect these stipulations, and that for many years these laws were properly executed. In 1860 the most recent of these “passed laws” was the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Passed on September 18, 1850 by Congress, the Fugitive Slave Act was part of the Compromise of 1850.[12] The Act required that escaped slaves be returned to their owners, even if they were in a free state; and also made the federal government responsible for finding, returning, and trying escaped slaves. Across the 1850s, as the abolitionist movement grew in the North, along with the general awareness of the immorality inherent in slavery, the Fugitive Slave Act gradually became unenforceable, and that is what South Carolina, the first state to secede, was complaining about. With the election of Lincoln in 1860, whom many Southerners feared would want to free the slaves, the proverbial straw was placed; and it would require four years of bloody carnage and over 600,000 dead soldiers between both sides to at last resolve the issue of slavery in the United States.

September, 1862

Of course, resolving the slavery issue did not resolve the problems of discrimination and racism in the United States, and particularly in the South. In the years following the Civil War a suppressive system akin to apartheid was implemented there—the Jim Crow Laws—designed to continue the denial of basic human rights to free Blacks. Jim Crow would continue in the South for more than 70 years, weakening only when the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and ‘60s came along. Personally, I choose to believe this is what William Faulkner, a lifelong Southerner, was alluding to with his clever line mentioned at the outset of this article: “The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.” For the decades following the Civil War in the South, that certainly seemed to be the case.

Moreover, when Thomas Jefferson penned that short piece of truth, “all men are created equal”, in the Declaration of Independence, our nation’s most basic founding document, he cast in stone forever the central premise of the United States of America. Despite the long failure of many of those who came before us to adhere to its ideal, including Jefferson himself, that statement IS the rock that slavery ultimately broke itself on; as well as Jim Crow. And If the day ever comes in this country when we can truly leave the past in the past, along with its racism and injustice, then perhaps we can have the righteous society envisioned by Jefferson’s words.

It falls to each of us as citizens, in our dealings with each other and in our civic responsibilities, to speed along that day’s arrival.

Copyright © 2020

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1]William Faulkner (1897 – 1962) is one of the most celebrated writers in American literature generally and specifically Southern literature. A Nobel Prize laureate from Oxford, Mississippi, Faulkner wrote novels, short stories, screenplays, poetry, essays, and a play. He is primarily known for his novels and short stories set in and around the town of Oxford, where he spent most of his life. One of his novels won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1949, while two others were Pulitzer Prize winners. He died in 1962 after a serious injury received in falling from a horse.

[2] “Jim Crow” was a derogatory term for a Black person that started in the 1830s, most likely from a popular song and dance called “Jump Jim Crow” which was performed in “black face” at the time by a white comedian named Thomas Dartmouth Rice. The song was supposedly inspired by a disabled Black slave named Jim Cuff or Jim Crow. I have encountered other explanations for the term, but this one is the most plausible to me.

[3] “Lineaments” are distinctive features or characteristics

[4] “Execration” means the act of cursing or denouncing, or the curse so uttered. Also, an object of curses or something detested.

[5]“Amor patriae” means love of one’s country; patriotism

[6] “Evanishment” means the act or process of vanishing : disappearance of something. I am still wrestling with Jefferson’s use of the word in this context, thus am not exactly sure what he means by the phrase, “…contribute as far as depends on his individual endeavours to the evanishment of the human race…”

[7] “Mollify” means to appease the anger or anxiety of someone.

[8] “Extirpation” means the complete destruction or extermination of something

[9] The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) was a slave revolt in the French colony of Saint-Domingue which culminated in the elimination of slavery there and established the Republic of Haiti. It was the only slave revolt in the modern era that led to the founding of a state and is generally considered the most successful slave rebellion ever to have occurred in the Americas.

[10] For the full history of the founding of Liberia by free American Blacks please see “Human Rights at the Crossroads: A Short History of Liberia” Parts I and II at my http://fromanativeson.com/ website. The two articles are linked here: http://fromanativeson.com/2015/04/26/human-rights-at-the-crossroads-a-short-history-of-liberia-part-i-by-mark-arnold/ and http://fromanativeson.com/2015/05/01/human-rights-at-the-crossroads-a-short-history-of-liberia-part-ii-by-mark-arnold/

[11] The Liberian Civil War was an extremely violent internal civil war in the West African nation of Liberia comprised of two conflicts; the first from 1989 until 1997 and the second from 1999 to 2003. The conflict killed an estimated 250,000 people and eventually led to the involvement of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and of the United Nations.

[12] The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican-American War. It also set the western and northern borders for Texas and included provisions addressing fugitive slaves (The Fugitive Slave Act) and the slave trade. The compromise was brokered by senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and Democratic senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois, with the support of President Millard Fillmore

6 Responses

Thanks–will share else with you later.jo

Thanks, Joline! Look forward to it. L Mark

Well written . Thanks for talking the time to add clarity to an issue , which for most ,remains murky. Should be read by every high school student.

Thanks, Roger, and you’re welcome! This was an interesting one to research and write, thats for sure! More to come…L M

Mark,

Well written. Thank you for this. There is always something to learn. I totally agree with you on our founding documents. When they were written, perhaps Jefferson was hoping for a better tomorrow that’s he knew he could not reach at that point in time. At least that is what I would like to believe. Those documents are a guidepost for us – into the future.

Perhaps one day we will have the opportunity to exchange ideas and thoughts on this.

Thanks, Denice! Operating from what Jefferson writes, which is all we can do at this point, leads me to the conclusion that he was terribly conflicted on the subject of slavery. I believe that he ethically and morally knew slavery was wrong AND that his confront on the subject was low because of his own overts in the area. I also think that when he wrote those great words in the Declaration he set in motion the ultimate solution for the problem. Ever since then we as a society have been struggling to live up to those words, and any progress we have made stems from the degree we’ve succeeded. Would love to talk more with you when we can get together. L Mark