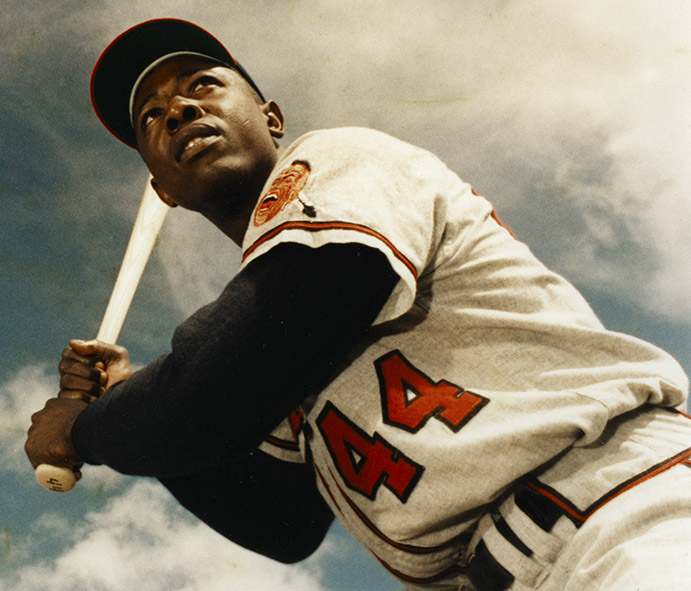

Note: As a kid growing up in Seattle in the 1950s and ‘60s, baseball was my favorite sport, the Milwaukee Braves were my favorite team, and Hank Aaron was my favorite player. Those years were a kind of golden age for the game. With Jackie Robinson, in 1947 baseball’s color line was at last broken, and soon came the arrival to the Major Leagues of a backlog of great Negro League players, such as Larry Doby, Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and Monte Irvin; followed later by Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Billy Williams, Ernie Banks and, for my money, the greatest of them all, Hank Aaron. With Aaron’s death this last January at the age of 86, former and current players, managers, fans and sports writers have been sharing their recollections of the man who shattered the career home run record of the great Babe Ruth. I am pleased to add to this collection my own tribute to my personal boyhood baseball hero, entitled “Saying Goodbye to Hammerin’ Hank Aaron.” Presented here is Part IV of the tribute, and as it builds on the information in Parts I, II and III it is suggested that those be read in sequence prior to Part IV. For ease of access I have linked those installments below. With that understood, I invite you to read on…MA

__________________________________

historic “Shot heard round the world” to

win the 1951 NL Pennant

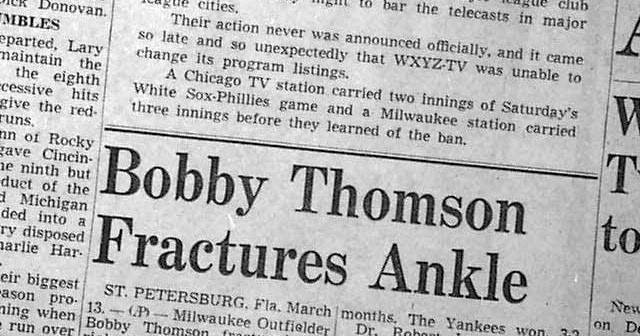

In early August of the 1951 season the Brooklyn Dodgers were leading the National League by 13 ½ games over the New York Giants. Then, in one of the epic stretch run collapses in Major League history, the Dodgers blew every bit of that 13 ½ game lead to wind up the season deadlocked with the Giants; both teams registering 96 wins against 58 losses. To break the tie and determine the 1951 NL Pennant winner, a 3-game playoff was scheduled, which took place on October 1st, 2nd and 3rd. The Giants won the first game and the Dodgers took the second, which set up the deciding 3rd game, to be played at the Giants Polo Grounds home ballpark. Going in to the bottom of the 9th of that game the Dodgers were leading 4-1, and it looked for all the world like Brooklyn would take the National League flag. But then the miraculous happened. In one of baseball’s storied moments, Giants outfielder Bobby Thomson hit a 3-run, walk-off home run; the legendary “shot heard around the world,”[1] at once stealing the pennant from the Dodgers and delivering it to the Giants. At the exact moment that Thomson was launching his historic home run, then 17- year old Hank Aaron was walking down Davis Avenue in Mobile, Alabama. In those days businesses on the street would often have the game blaring from radios inside, and as he walked Hank had no problem following the action. When he heard the Giants announcer Russ Hodges [2]calling Thomson’s game-winning blast, he was so excited that he ran all the way home, all the while imagining that he was Thomson, circling the bases and being mobbed by his teammates at home plate. It was an inspiring moment for Aaron, and one that elevated Bobby Thomson to hero status in his universe. He didn’t know it then, but in one of those delicious ironies that dot baseball history, Thomson would later play a key role in helping Hank make it to the Major Leagues.

Following his 1953 Sally League[3] MVP season with the Jacksonville Braves, it was obvious to baseball people that Hank Aaron was a remarkable talent, especially when it came to hitting. Fielding, however, was another matter. An infielder in his first two seasons as a professional, first at shortstop with the Indianapolis Clowns and the Eau Claire Monarchs, and then at 2nd base with Jacksonville, where Felix Mantilla[4] played shortstop, Aaron could never master the myriad intricacies of infield play. At Jacksonville, besides his league leading hitting, he also led the league in errors with 36; a situation which led to the next major change in his career. A short while after the ’53 season ended, Felix Mantilla asked Hank to come and play winter ball in Puerto Rico. The Milwaukee Braves (the Boston Braves had moved to Milwaukee in the spring of 1953[5]) player development people thought it was a good idea; and though he had recently married and now had a young wife, Aaron agreed. Thus, he and his bride packed up and headed off to the Caribbean.

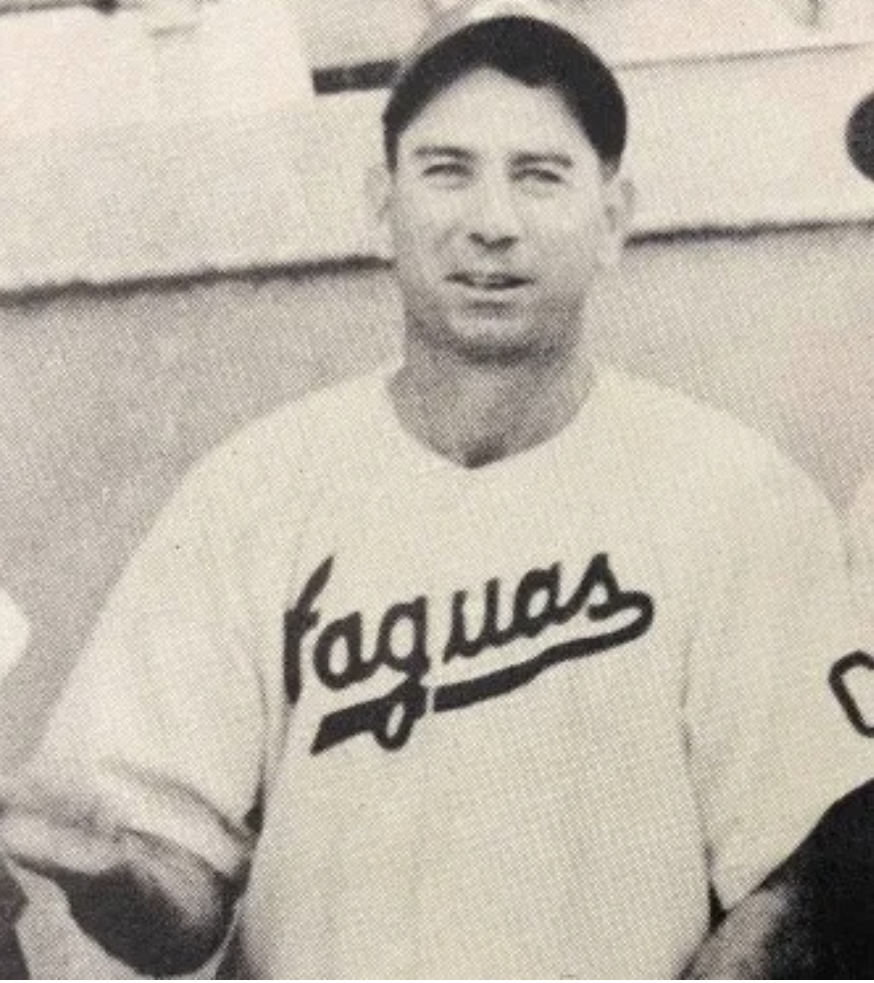

For a young hitting talent like Hank, the Puerto Rican League was a perfect training ground. There were many big-league pitchers playing winter ball there, and that gave Hank and the Braves a chance to see how ready he was for the Majors. Aaron started that winter league season at 2nd base for his team, the Criollos de Caguas,[6] but after a couple weeks of play he was struggling in the field and at the plate, hitting only .125. With the Korean War having just ended and the Cold War ramping up, also hanging over the young player’s head was a potential military draft call-up back in the States. Between that and his poor play, the Caguas team was considering sending him back home, but the Braves and Hank’s friend Felix Mantilla intervened on his behalf, convincing the team to keep him in Puerto Rico. It was then that the Caguas manager, a former big league catcher named Mickey Owen[7], pulled Aaron aside and suggested to him what turned out to be a career changing move. As quoted in “I Had A Hammer,” Owen himself describes the moment and what then happened:

“I said, ‘Henry, how about trying the outfield?’ He said, ‘Okay, I’m going into the army anyway. I’ll do whatever you want until the draft board calls.’ I sent him out there and hit him some fly balls. He just turned and ran and caught them. I thought, well, he can catch the ball, but can he throw it? I’d never seen him throw any way but underhanded. So I hit him some ground balls and told him to charge and throw them to second base. He threw the ball overhanded, right to second base. Then I told him to cut loose and throw one to third. So he cut loose and that ball came across the infield as good as you ever saw. That was it. He was an outfielder.”

After Hank’s conversion to the outfield, as he had done with every other team in his professional career, he went on to have a great winter league season for Caguas, finishing 3rd in the league in hitting with a .322 average, while also hitting a league leading 9 home runs. Impressed as he was by Aaron’s prowess at the plate, in “I Had A Hammer” Owen shares his thoughts on Hank as a hitter:

Mickey Owen

“He could hit a ball out of any ballpark, but what I liked was the way he hit to all fields. One of the first days he was there I saw him rifle a ball past the first baseman, like a bullet, and I said to myself, My God, he looks like Rogers Hornsby. I asked him if he had tried to hit the ball to right field, and he said he didn’t know if he did or not. I said, well, whatever you did, keep at it. I can remember exactly what I said to him. I said, ‘Don’t let anybody change you, because you’re going to be a good hitter and probably a great hitter if you take care of yourself.’ I could just see Hornsby in him, the way he would take that whip swing and drive the ball all over the ballpark. Both of them would get that big end of the bat around so fast…”

Following his Puerto Rican winter ball campaign, Hank returned to Mobile to await the start of spring training for the upcoming 1954 season. Initially it appeared that Hank, Mantilla and their old friend Horace Garner would be assigned to the Braves’ AA affiliate in the Southern Association, the Atlanta Crackers.[8] The Southern Association was another southern minor league that still needed to be integrated, and the Braves had used the social importance of that to prevail upon the draft board to allow Aaron to continue with baseball in lieu of the Army. At some point, however, probably due to his performance in Puerto Rico, the speculation shifted to Hank being sent to the Braves’ AAA farm team in Toledo. As far as Hank, himself, was concerned, neither of those options would do. He felt that given a fair chance he would show he was ready, and would earn a spot on the Milwaukee Braves big league roster. As it turned out, with some fateful assistance from Hank’s other baseball hero (besides Jackie Robinson), Bobby Thomson, that’s exactly what happened.

door for Aaron, 1954

In the winter following the 1953 season the Milwaukee Braves acquired Bobby Thomson in a trade with the New York Giants. Already famous for his magical pennant winning homer in 1951, Thomson was a first-rate Major League outfielder and 3-time All Star who had hit .288 for the Giants in 1953, with 26 home runs and 106 RBIs. On the face of it, his arrival at the Braves spring training camp, along with veteran Braves outfielders such as Andy Pafco, Bill Bruton and Jim Pendleton,[9] made Hank’s prospects for making the team seem remote. Nevertheless, Aaron had been invited to the big club’s spring training, and he intended to make the most of it; and that is when fate stepped in to lend a hand. For the second time in his young career, an injury to a veteran player, this time to the legendary Bobby Thomson, would open the door for Hank Aaron, and he wasted no time in walking through it. Thomson’s injury occurred when the Braves were playing the Yankees in a spring training game in St. Petersburg, Florida. Hank had played earlier in the day in a split-squad game and was watching as Thomson attempted to slide into second base:

“I was standing in a little alleyway behind third base drinking a soda when Thomson’s leg folded under him as he slid into second base. They put him on a stretcher and carried him right past where I was standing. It was a horrible thing to watch, and it never occurred to me that it was my chance to play left field for the Braves…The next day I was starting against the Red Sox in Sarasota.”

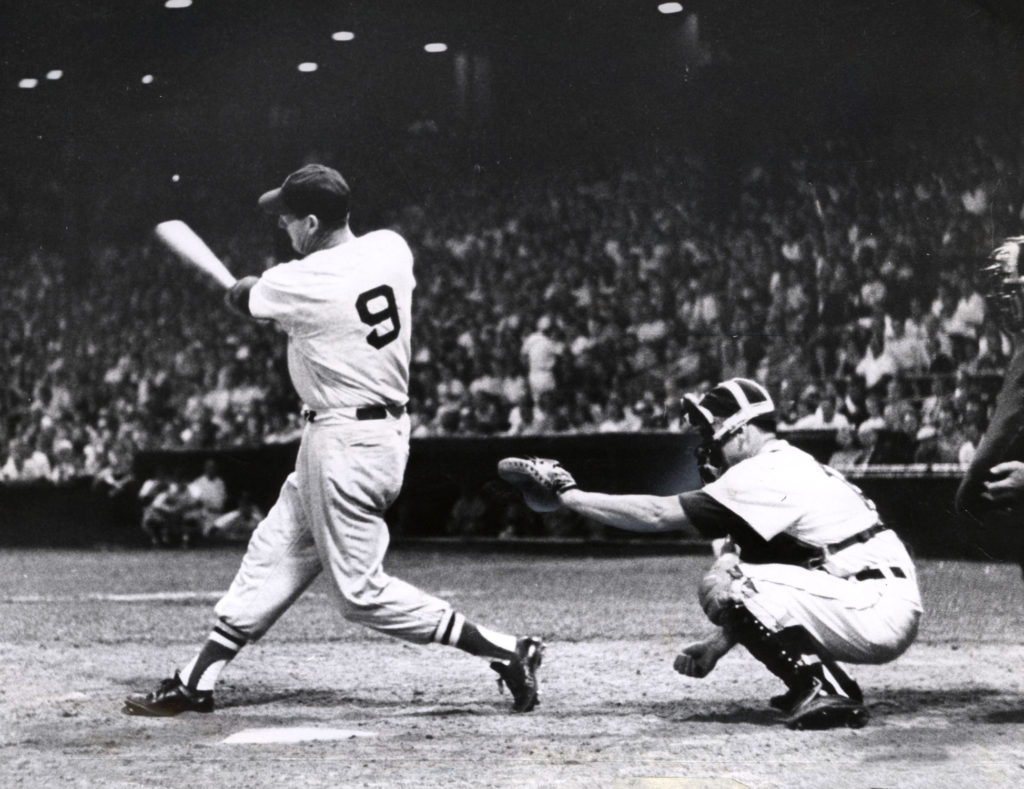

Ted Williams

In that game against Boston, Hank got another break because the Red Sox were starting a pitcher he was already familiar with from his prior season with Jacksonville. He had homered off that pitcher in that earlier game back in the Sally League, and he did it again against the Red Sox, driving the ball over the outfield fence and beyond a row of trailers parked on the other side. Playing with the Red Sox in those days, having recently returned from serving as a Navy/Marine fighter pilot in the Korean War, was the man many regard as the greatest hitter ever, Ted Williams.[10] Williams was in the Sox clubhouse when Hank hit the dinger, but even there could hear the crack of the bat when the young Braves outfielder connected. On hearing that sound Ted came rushing out of the clubhouse, wanting to know who could hit a ball so hard as to make a sound like that. The Red Sox legend had just been introduced to the man who would come to be known as Hammerin’ Hank Aaron.

No one bothered to tell him at the time, but Hank later read in the newspapers that Braves manager Charlie Grimm,[11] after seeing that game, had decided the young hitting phenom would be the team’s left fielder to start the season. Being left out of the loop, as spring training wound down Aaron was on pins and needles about whether he would make the team, and it wasn’t until he was handed his Major-League contract, just before the team headed north to start the season, that he knew he’d done it. “After that,” as Hank says in his book, “it would be about twenty-three years until I was out of the starting line-up.”

As he entered his 1954 rookie season with the Braves, Hank Aaron was 20 years old. He would finish that campaign with a .280 batting average, 13 home runs and 69 RBIs; good enough for 4th in the 1954 National League Rookie of the Year voting. If there was still any doubt that he belonged in the big leagues, he removed it with the season he had in 1955, when he hit for a .314 average with 27 dingers and 106 RBIs, while being selected as an All-Star for the first of the 21 consecutive seasons he would be so honored. In 1956 he led the league in hitting (.328), hits (200), doubles (34) and total bases (340), while finishing 3rd in National League MVP voting. By then the Braves, who had finished the 1956 campaign in 2nd place with a 92-62 record, were on the verge of becoming a pennant winning team, and Hank was one of the huge reasons why. The team was loaded with superb players like pitchers Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette and Bob Buhl,[12] and hitters like third baseman Eddie Mathews,[13] first baseman Joe Adcock, catcher Del Crandall, and outfielder Bill Bruton. But, as the next season would demonstrate, none were better than Aaron.

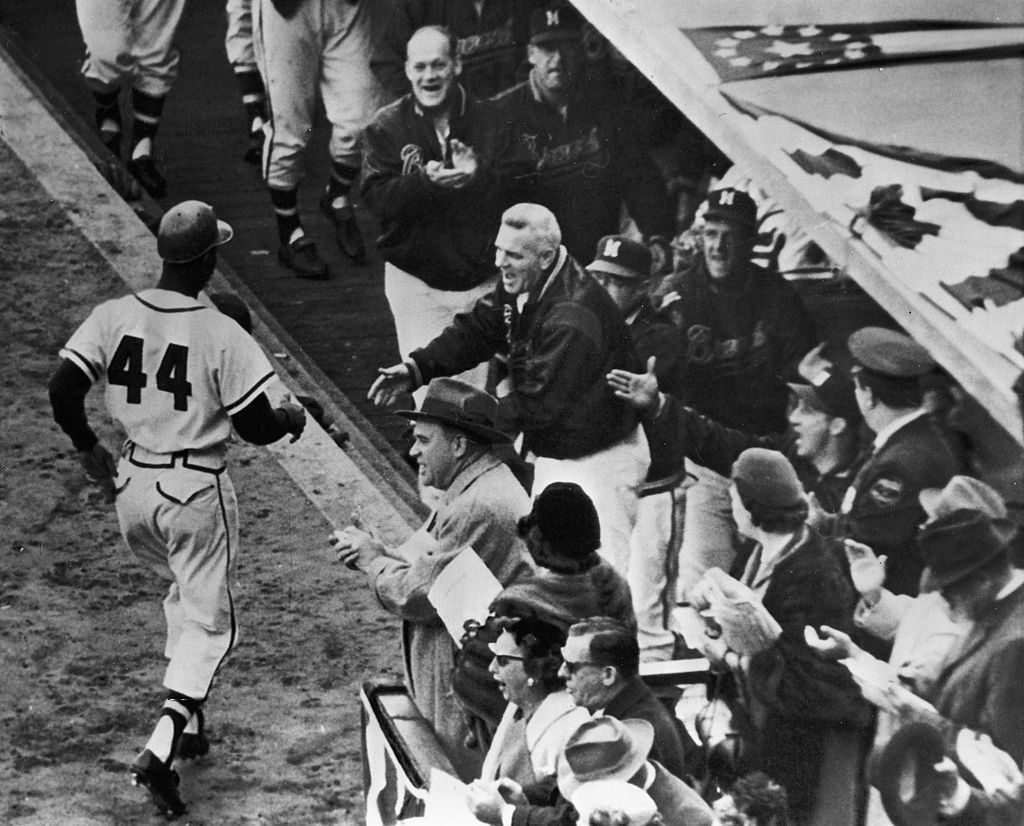

of his 3 home runs in the ’57 Series

vs. the Yankees

In 1957 Hank elevated himself to the status of super-star in Major League baseball. That year he led the Braves to the National League pennant while leading the league in home runs (44), runs (118), RBIs (132) and total bases (369). His walk-off home run in the bottom of the 11th inning against the Cardinals clinched the pennant for his team that season; and in the ‘57 World Series against the Yankees, largely because of Aaron’s play, the Braves became Series champions for the first time since 1914, when the team played in Boston and featured a remarkable pitcher named Babe Ruth.[14] For the Series Hank hit .393 with 3 home runs, 1 triple, 7 RBIs, 5 runs scored and a plus .400 on base percentage (OBP), as the Braves took 4 of the 7 games against New York. To top it off, with all of that regular and post season production under his belt, Aaron took home the 1957 National League MVP award. By any measure, at the age of 23, Henry Aaron had arrived as one of the elite players in Major League baseball.

Milwaukee won the National League pennant again in 1958, this time losing the World Series to the Yankees in 7 games after squandering the last 3 games in a row. That season would be the last time Aaron played on a pennant winner in his career, but the blame for that can hardly be placed on him. In the 12 seasons from 1959 through 1971 Hank would hit 40 or more home runs 8 times; never fewer than 24 (1964) or more than 47 (1971). During that same stretch, he drove in 100 or more runs 9 times; scored 100 or more runs 11 times; and hit .300 or better 10 times. When you sit back and look at his season after season production, as stellar as his stats are, the thing that stands out is his consistency, which was metronome-like: wind him up at the beginning of each campaign and you’d get your 40 dingers, 100 RBIs and 100 runs, it seems. Before the 1966 season the Braves made the move from Milwaukee to Atlanta, thus becoming the first Major League team in the deep South; fitting for Hank, as he had been among the first to integrate the southern minor leagues 13 years earlier. Baseball wise, however, based on his stats, where he played made no difference. North, south, at home or on the road; in the minors, Majors or Negro Leagues, Hank Aaron was simply a great baseball player.

As noted at the outset of this series, I followed Hank’s career closely in the daily sports pages and box scores across the entire decade of the 1960s and on into the 1970s. For most of that time the idea that he could possibly challenge Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record of 714 never crossed my mind. I was simply following him because I loved baseball and he was my favorite player. As good as Hank was, I remember thinking, when he finished the 1968 season with “only” 29 homers, that age must be catching up with him; that perhaps he was winding down. By then he had firmly established himself as a Hall of Fame player, one of the best ever, and I was thinking that we probably shouldn’t expect too much more from him as he advanced into his mid to late 30s. Then came the 1969 season, and Hank demonstrated to the world that he was nowhere close to “winding down.” In leading the Braves to the National League playoffs that year, Aaron blasted 44 long balls while hitting .300 with 97 RBIs, 100 runs scored, and a league leading 332 total bases. He topped off that season with an incredible performance in the playoffs. In the first ever National League Championship Series against the “Amazin’ Mets,”[15] he whacked 3 more home runs, hit .357 for the Series and drove in 7 runs. Though the Mets, who would go on to win the World Series that year, swept the Braves in 3 games; once again it obviously wasn’t because of Aaron.

For me, it was in the wake of Hank’s 1971 season that I began to think he had a real shot at Ruth’s record. He had a good season in 1970, with 38 homers and 118 RBIs, but the following season he was just unreal. Despite being 37 years old, in that ’71 campaign Aaron hit more home runs (47) than he ever had in a single season. He also hit .327; drove in 118 runs; had a .410 OBP; the best slugging percentage of his career with a league leading .669; and the best ‘on-base plus slugging’ (OPS) of his career at 1.079, which also led the league. He even led the league in intentional walks. Amazingly, he wasn’t slowing down as I expected he would—he was getting better. By the end of that 1971 season, for his career Hank had launched 639 home runs—76 short of the record. If he could stay healthy, I thought, he just might do it.

As it turned out, I should never have doubted him.

To be continued…

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2021

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] In Major League Baseball, the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” was a game-winning home run by New York Giants outfielder and third baseman Bobby Thomson off Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca at the Polo Grounds in New York City on October 3, 1951, to win the National League (NL) pennant. Thomson’s dramatic three-run homer came in the ninth inning of the decisive third game of a three-game playoff for the pennant in which the Giants trailed, 4–1 entering the ninth, and 4–2 with two runners on base at the time of Thomson’s at-bat. The game—the first televised nationally—was seen by millions of viewers across America and heard on radio by millions more.

[2] Russell Pleasant “Russ” Hodges (June 18, 1910 – April 19, 1971) was an American sportscaster who did play-by-play for several baseball teams, most notably the New York and San Francisco Giants. On October 3, 1951, Hodges was on the microphone for Bobby Thomson’s Shot Heard ‘Round the World. It was Hodges who made the iconic call, “The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!”, which has been used by other broadcasters down through years making calls of other game winning hits or home runs.

[3] “Sally League” is simply a play on the acronym SAL, which stands for “South Atlantic League;” a professional minor league including various teams in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas and Tennessee. The “Sally League” was started in 1904.

[4] Félix Mantilla Lamela (born July 29, 1934) is a Puerto Rican former professional baseball utility player, who appeared mostly as an infielder. In his 11-year Major League Baseball (MLB) career, Mantilla played for the Milwaukee Braves (1956–61), New York Mets (1962), Boston Red Sox (1963–65), and Houston Astros (1966). He played second base the majority of his big league career (326 games), but also adeptly played shortstop (180), third base (143), outfield (156) and (in the latter part of his career), first base (16). Mantilla batted and threw right-handed. In 1953, Mantilla (along with Hank Aaron and career minor league outfielder Horace Garner) joined the Class-A Minor League Baseball (MLB) Jacksonville Braves, of the South Atlantic League — which was (at that time) one of the first two integrated baseball teams in the Southern United States. Mantilla and Aaron were roommates. In 1954, Both Mantilla and Aaron were vital contributors to Milwaukee winning the 1957 World Series title over the New York Yankees.

[5] Founded in 1871, the Boston Braves were a franchise in Major League Baseball’s National League for 81 years, until the team relocated to Milwaukee before the 1953 season. The Boston Braves were the original team of Babe Ruth, who was primarily a pitcher, and a very good one, until the Braves traded him to the New York Yankees following the 1919 season.

[6] In Puerto Rico natives of the town of Caguas are usually referred to as “criollos”; professional sports teams from that town are also usually nicknamed “Criollos de Caguas” (“Caguas Creoles”). Caguas is located near Puerto Rico’s Cordillera Central mountain area.

[7] Mickey Owen (1916-2005) besides being Aaron’s manager in Puerto Rico, was a catcher who played 13 years in the major leagues, achieving prominence in the war years when he was an All-Star four times. He was 4th in the MVP voting in 1942. He appeared in the 1941 World Series batting usually eighth but sometimes seventh in the lineup. He is most famous for dropping a third strike pitch from Hugh Casey to Tommy Henrich of the New York Yankees with two outs in the 9th inning of Game 4 of the Series. Henrich reached first base, and the Yankees scored four runs to turn a 4-3 loss into a 7-4 victory. Once his playing career ended, Owen was a Boston Red Sox coach in 1955 and 1956. He was also a minor league manager (1953 and 1957) for the New York Yankees (‘57) and Milwaukee Braves (’53) and a scout for the Baltimore Orioles in 1958-1959.

[8] The Atlanta Crackers were Minor League Baseball teams based in Atlanta, Georgia, between 1901 and 1965. The Crackers were Atlanta’s home team until the Atlanta Braves moved from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1966.

[9] Andy Pafco in 1957 was a 14-year veteran, 4 time All Star with a career .285 batting average and 200 career HRs; while Bill Bruton, who was Black, was a 4-year veteran centerfielder with great speed. By ’57 he had led the National League in steals 3 times and in 1956 led the league in triples with 15. Jim Pendleton, like Aaron, was a former Negro League player, who had something of a journeyman career in the Majors. His best season by far was in 1953 when he played in 120 games as a rookie, hitting .299 with 7 homers, including a rookie record 3 in one game (tied with teammate Eddie Mathews, who also hit 3 in one game in his rookie season of 1952.)

[10] Considered by many to be the greatest hitter who ever lived, Ted Williams (1918-2002) played 19 seasons in the Major Leagues, all with the Boston Red Sox. A 17 time All Star, for his career he hit .344 with 521 home runs, 1839 RBIs and a Major League record on-base percentage of .482. When you consider that Williams missed 3 full seasons in his prime due to service in World War 2, and most of 2 others due to the Korean War, it’s entirely possible that he could have challenged Ruth’s career HR record before Hank Aaron came along.

[11] Charles John Grimm (August 28, 1898 – November 15, 1983), nicknamed “Jolly Cholly”, was an American professional baseball player and manager. He played in Major League Baseball as a first baseman, most notably for the Chicago Cubs; he was also a sometime radio sports commentator, and a popular goodwill ambassador for baseball. He played for the Pittsburgh Pirates early in his career, but was traded to the Cubs in 1925 and worked mostly for the Cubs for the rest of his career. Grimm was manager of the Milwaukee Braves from 1953 to 1956.

[12] Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette and Bob Buhl gave the Braves 3 outstanding starting pitchers in their rotation for their pennant winning years of 1957-58. Spahn (1921-2003) quite simply is one of the greatest pitchers ever. Elected to the Hall of Fame in 1973, his 363 career victories are more than any southpaw who ever lived. Like Williams, Spahn lost 3 prime seasons due to World War 2, most likely costing him at least 50 wins and possibly 60. In ’57 he went 21-11 and in ’58 he went 22-11. He was a 14 time All Star. Lew Burdette (1926-2007) played 20 seasons in the Majors, 13 with the Braves, and won over 200 games while making the All Star team twice. In 1957 he went 17-9 and won the World Series MVP award after defeating the Yankees 3 times in the Fall Classic. In 1958 Burdette won 20 games for the first time in his career, going 20-10 with a 2.91 ERA and 19 complete games. Though missing most of 1958 due to injury, Bob Buhl (1928-2001) went 18-7 in ’57 and won over 160 games across his 15-year career.

[13] Edwin Lee Mathews (October 13, 1931 – February 18, 2001) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) third baseman. He played 17 seasons for the Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves (1952–1966); Houston Astros (1967) and Detroit Tigers (1967–68), Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1978, he is the only player to have represented the Braves in the three American cities they have called home. He played 1,944 games for the Braves during their 13-season tenure in Milwaukee—the prime of Mathews’ career. Mathews is regarded as one of the best third basemen ever to play the game. He was an All-Star for nine seasons. He won the National League (NL) home run title in 1953 and 1959 and was the NL Most Valuable Player runner-up both of those seasons. He hit 512 home runs during his major league career. Mathews coached for the Atlanta Braves in 1971, and he was the team’s manager from 1972 to 1974, and was on that post when Aaron broke Ruth’s career home run record. Mathews and Aaron also hold the MLB record for most home runs hit by teammates with 863

[14] George Herman “Babe” Ruth Jr. (February 6, 1895 – August 16, 1948) was an American professional baseball player whose career in Major League Baseball (MLB) spanned 22 seasons, from 1914 through 1935. One of the best hitters who ever lived, Ruth’s ability at the plate often obscures what a great pitcher he was during the early years of his career with the Boston Braves before he was traded to the Yankees. As a pitcher, he had a career record of 94-46 with a career ERA of 2.28. His best seasons were 1916 when he went 23-12 with an ERA of 1.75, and 1917 when he won 24 against 13 losses with a 2.01 ERA.

[15] The 1969 New York Mets season was the team’s eighth as a Major League Baseball (MLB) franchise and culminated when they won the World Series over the Baltimore Orioles. They played their home games at Shea Stadium and were managed by Gil Hodges. The team is often referred to as the “Amazin’ Mets” (a nickname coined by Casey Stengel, who managed the team from their inaugural season to 1965) or the “Miracle Mets“. The 1969 season was the first season of divisional play in Major League Baseball. The Mets were assigned to the newly created National League East division. In their seven previous seasons, the Mets had never finished higher than ninth place in the ten-team National League and had never had a winning season. They lost at least one hundred games in five of the seasons. However, they overcame mid-season difficulties while the division leaders for much of the season, the Chicago Cubs, suffered a late-season collapse. The Mets finished 100–62, eight games ahead of the Cubs. The Mets went on to defeat the National League West champion Atlanta Braves three games to none in the inaugural National League Championship Series. The Mets then went on to defeat the American League champion Baltimore Orioles in five games.