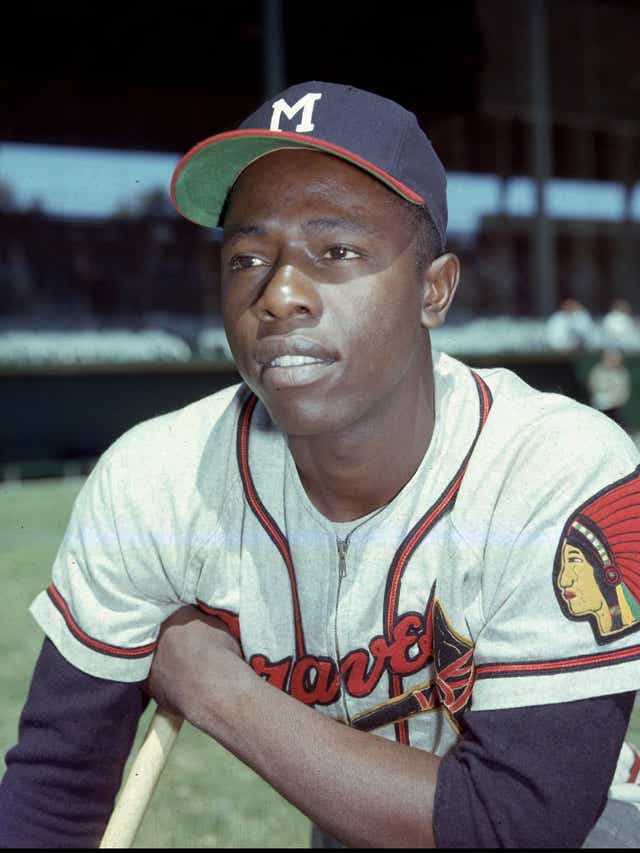

Note: Presented here is Part II of my personal tribute to my boyhood baseball hero, Hank Aaron, who passed away on January 22nd in Atlanta. Few players have ever accomplished as much in their careers as Aaron did, or had to overcome as much along the way. Fewer still did it with the grace and humbleness he embodied throughout his 23 years in the Major Leagues. As a young kid growing up in a south Seattle suburb in the late 1950s, who was also developing an intense love of baseball, I was quick to recognize Hank’s talent and he rapidly became my favorite player on my favorite team, the Milwaukee Braves. From that point on I followed his career across a thousand sports pages and box scores, all the way to his breaking of Babe Ruth’s all-time career home run record in the spring of 1974, and on to his 1982 induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame as one of the greatest players who ever lived; a fact evidenced by Hank’s career stats. When he finally hung ‘em up after the 1976 season, Aaron had not only shattered Ruth’s career home run record of 714, but also had more extra base hits (1,477), more RBIs (2,297) and more total bases (6,856) than any player who ever lived. Throw in the 3rd most hits ever (3,771), the 4th most runs scored ever (2,174), 3 outfield Gold Gloves and 21 consecutive All-Star selections (1955-1975,) and one is confronting a career of unquestioned magnificence; made better by the fact that he was as good a human being as he was a ballplayer. To get the most out of this article I highly recommend reading Part I first, which is linked here:

With that preamble understood, here is “Saying Goodbye to Hammerin’ Hank Aaron-Part II”. I hope you enjoy it. MA

_______________________________________

When Hank Aaron boarded that train to Winston-Salem in 1952, he carried with him an envelope, given to him by his Mobile Black Bears manager Ed Scott and to be delivered by Hank to Bunny Downs,[1] then the business manager of the Indianapolis Clowns. As he sat there on that train ride, a frightened 18-year old heading off towards an uncertain future, Aaron must have wondered what message the envelope contained; but as the contents were not intended for him, he did not open it. Many years later Hank found out that Scott’s message to Bunny Downs was comprised of a single sentence:

“Forget everything else about this ballplayer,” the note said, “just watch his bat.”

Perhaps never in the history of baseball has a more prophetic statement been made about a young player who had yet to prove himself against quality competition. It didn’t take long, however, for Hank to show just how right Ed Scott was.

With his arrival at Winston-Salem and the Clowns’ spring training, the veteran Indianapolis players looked askance at the young player from Mobile who was trying to make the team. After all, for Aaron to succeed meant that one of them would be eclipsed in the process, and so young “up and comers” like Hank were initially often resented—that is until they proved themselves. But to prove oneself required an opportunity, which the veterans were loath to provide. Patience, therefore, is a great virtue for a young player; so, tough though it was, Hank bided his time, waiting for a break. That break came right before the team started playing their spring exhibition games. In his book, “I Had A Hammer,” Aaron describes his big opportunity as follows:

“I might never have gone on the road (to start the season), though, if one of the regular infielders hadn’t gotten hurt about the time we started playing exhibition games. When that happened, Haywood (Buster Haywood, field manager of the Clowns)[2] had to put me in the lineup—everybody else was either hurt or a pitcher—and as soon as I got to the plate the hits started to fall…”

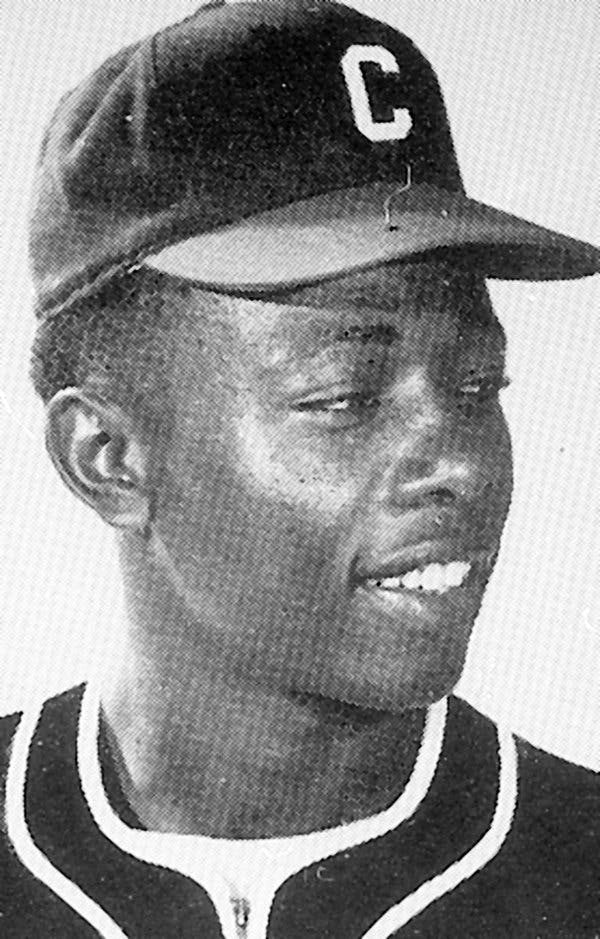

Indianapolis Clowns

All sports have their share of legends about players getting their initial break when another player gets injured, and then becoming mega-stars. The most famous example of this in baseball took place in the 1925 season when a Yankees first baseman named Wally Pipp, [3] who was really quite a good player, was beaned in batting practice and developed a headache (today we’d call it a concussion) and told his manager, Miller Huggins,[4] that he would prefer to sit out that day. Huggins replaced Pipp with a player named Lou Gehrig,[5] and the rest, as they say, is history. Gehrig went on to become, perhaps, the best first baseman in the history of the game, while Pipp was relegated to a humorous historical footnote; thereafter being best known as a verb—whenever fans state that a player was “Wally Pipped,” you know just what they mean. Aaron benefitted from two such instances early in his career, the first being the time just described with the Clowns, and the second a couple years later when he cracked the Milwaukee Braves lineup in a similar fashion—but we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Suffice it to say, the minute Hank got on the field for the Clowns with regular playing time, everyone in the ballpark was forced to watch his bat, just as Ed Scott had predicted.

Once the ’52 regular season started, for the next 2 months Aaron barnstormed with the Clowns across the south and on up the east coast, travelling by bus from town to town, playing out the team’s schedule. In those days Hank played shortstop, and he was an adequate infielder; but what set him apart, and drew the Major League scouts to him, was his talent as a hitter. In his book Aaron, himself comments on his developing reputation as a batsman at this early stage in his career:

“As frightened as I was about everything else, it never occurred to me that I might not hit. I got one-hop singles through the infield, low-riding doubles through the outfield, and a home run to right-center now and then. I tried to act like it was nothing, but I could tell that people were noticing me. It was a small league, and it didn’t take long to make a reputation.”

managed the Monarchs

Another comment on Aaron’s developing prowess as a hitter came from noted former Negro League player and manager, Buck O’Neil,[6] who in 1952 was manager of the Kansas City Monarchs;[7] the same Negro League team that Jackie Robinson [8]played with before Branch Rickey [9]signed him to the Dodgers. Early in that ’52 season O’Neil got to see Hank up close and personal when the Monarchs played a spring game against the Clowns, and came away impressed:

“The first time I saw Aaron we were playing the Clowns down in Alabama or Louisiana…I noticed this young boy hitting in the fourth spot, and I said, ‘Buster, what’s this kid hitting fourth?’ He said, ‘Buck, you just wait and see him swing the bat.’ Well, I had some pretty good pitchers who had been around the block a few times, and the first time he came up I told the pitcher to throw this kid a good fastball. He threw a fastball and the kid hit it up against the right field fence. The next time he came up I had my best left hander in there, and I said to him, now throw this kid a good fastball. He threw his fastball on the first pitch and the kid hit it against the centerfield fence. I looked over at Buster and Buster was just laughing at me. The last time, I had the star of my staff in there, an old pro named Hilton Smith, and I told Smith to throw this kid some curve balls. The kid hit a curve ball over the left field fence. I told Buster then… “Tell you what, You and I both know that by the time you get to Kansas City to play us, this kid won’t be with you anymore. No way a hitter like that was going to stay around the Negro League.”

with the Indianapolis

Clowns, Buster Haywood.

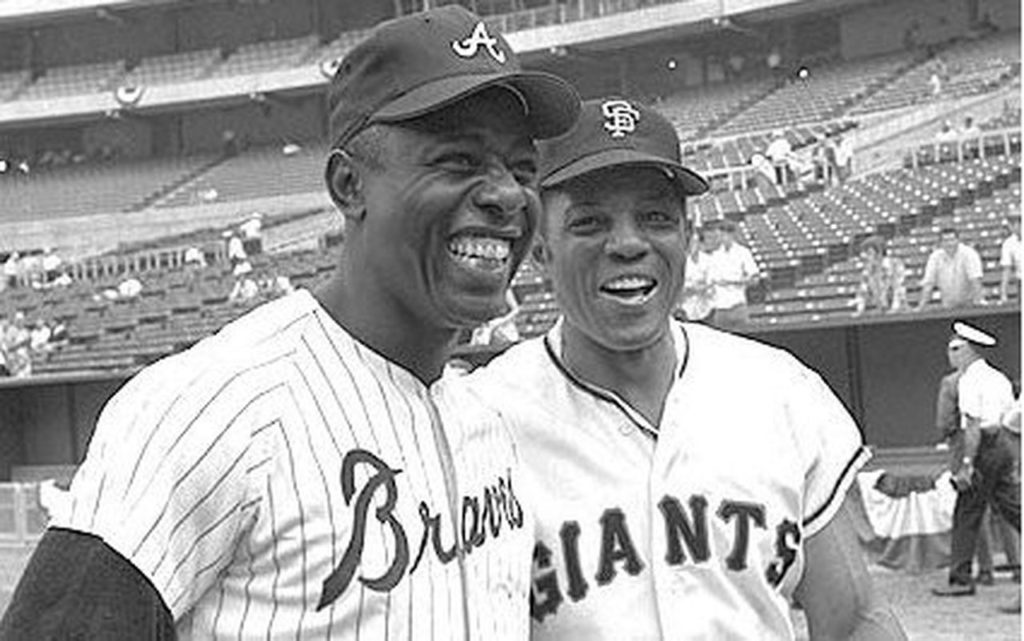

As with Ed Scott before him, Buck O’Neil’s assessment of Hank Aaron portended great things for the young player; and it wasn’t long before the Clowns shortstop with the incredible bat was drawing raves and big league scouts wherever he played. The Boston Braves had the inside track to Aaron because of a special relationship between the owner of the Clowns, a man from New York named Syd Pollock, [10] and the Braves farm director, John Mullen.[11] By this time in the early ‘50s, with the color barrier now broken in the Major Leagues, one of the ways the Negro League teams made money was by selling the rights to their best players to big league teams. Pollock and Mullen had conducted such transactions before, so when Pollock mentioned his 18-year old shortstop in a letter to Mullen, the Braves farm director and Pollock negotiated over the phone a 30-day option agreement during which the Braves had exclusive rights to sign Hank if they chose to do so. Mullen almost blew the deal, however, because he was late in getting one of his scouts, a man named Dewey Griggs,[12] to see Aaron play. Griggs scouted Aaron in games on the east coast, but didn’t actually contact him until weeks after Pollock and Mullen had made their agreement. That happened when the Clowns were playing a double header against the Memphis Red Sox in Buffalo, New York, and by then the 30-day option agreement had expired and scouts from other big league teams, most notably the New York Giants, were hot on Hank’s trail. As you may recall, the Giants had recently signed another young phenom out of the Negro leagues, a centerfielder named Willie Mays, and now they wanted Aaron. Imagine if they had succeeded, and Mays and Aaron had ended up playing 20 years together for the Giants—that would have been something! Largely due to Griggs, however, it didn’t happen.

Hank first met Dewey Griggs when he saw him standing by a guard rail separating the fans from the field after the first game of the double header against Memphis. The way he describes it in his book, their initial meeting had an immediate impact on Aaron’s play:

“It rained in Buffalo, but I had a good day against the Memphis Red Sox. I had a home run and a few other hits in the first game, and between games I noticed a man with a hat standing by the rail. You could always pick out a scout. He called me over to talk to him, introduced himself as Dewey Griggs of the Braves, and told me he was a little concerned about my style of playing. I had a habit of fielding the ball on one knee, and I would sort of flip it underhanded to first base. He didn’t know if I could really throw. Also, I used to ease around the field at about three-quarters speed most of the time, and he wondered if I could run. I said that my daddy told me never to hurry unless I had to, and it was advice that I believed in. But if he wanted to see me run and throw I’d do what I could. Mr. Griggs also suggested that I hold the bat with my right hand on top instead of cross-handed. / The first time I came to bat after that, I held the bat the right way and hit a home run. I never batted cross-handed again…”

After watching Aaron in the second game of the double header, Griggs sent a letter, dated May 25, 1952, to John Mullen in which he stated that, “Henry Aaron the 17-year old (sic)[13] shortstop of the Indianapolis club looked very good.” He went on to extoll Aaron’s fielding in the letter and lauded his hitting, commenting on the home run, a bases loaded single Hank hit off a curve ball, as well as a beautiful bunt the young player had executed. Griggs closed his letter to Mullen with the statement that, “This boy could be the answer.”

When John Mullen received the letter from his scout he realized that his exclusive 30-day window to sign Aaron had passed, and he immediately called Syd Pollock to see about getting the young hitter under contract with the Braves. Pollock wasn’t available to talk on that call, and when Mullen called back he must have feared the worst, as the Clowns owner told him that he’d been negotiating to sell Aaron to the New York Giants and was close to wrapping up the deal. It had only been a couple years earlier that the Braves had been on the verge of signing Willie Mays, only to have the Giants swoop in and sign him from under their nose. No way was Mullen going to let that happen with Aaron. He pressed Pollack to honor the 30-day agreement, even though it had technically lapsed, and finally the Clowns owner agreed that if Hank wanted to go with the Braves he would do business with Mullen. So, it was up to Hank; and in the end, because he felt the Braves offer to him was fairer overall, he signed with the National League team from Boston for $350 a month. The Giants offer was for $250 a month, and the Clowns and Syd Pollack would have received more money had they closed the deal with New York instead of Boston. But it didn’t happen; thus, the baseball world never got to see what likely would have been the greatest outfield in the history of the game—a Giants team with Willie Mays in centerfield and Hank Aaron in right.

The dream outfield that almost happened

By any measure, Hank’s few months in the Negro League with the Indianapolis Clowns were an unmitigated success. He led the league in hitting for most of the season, most likely batting more than .400 for much of the time, but there is no record of it as the statistics for that season have been lost. By his own recollection Hank thinks he had fallen below .400 by the time he left the Clowns in early June to report to the Braves, and he leaves it to others to argue about whether he led the league in hitting. He was more concerned with taking his next step in professional baseball, which would bring big changes for him. The team he was initially assigned to in the Braves minor league system was a club that played in the Class C Northern League called the Eau Claire Bears. In the early 1950’s the town of Eau Claire, which is in western Wisconsin, had a population of about 35,000 people, almost all white. To get there Hank had to take his first plane flight ever, and by his own admission the bouncy ride scared the hell out of him. The real challenge for Aaron, however, was adjusting to his new situation in Eau Claire. For a young 18-year old, Black ballplayer, who had lived his whole life in the deep South and who had never played with white players before, much less lived in a nearly all white town, well, I think you can appreciate how uncomfortable and foreign it must have been. Here is how Hank describes what it was like for him in those first few weeks at Eau Claire:

“Eau Claire was not a hateful place for a black person—nothing like the South—but we didn’t exactly blend in. The only other black man in town was a fellow who used to stand on the street corner flipping a silver dollar. Wherever I went in Eau Claire, I had the feeling that people were watching me, looking at me as though I were some kind of strange creature…If it was strange for those white folks in Eau Claire to be around black people, it was just as strange for me to be around them. There was nothing in my experience that prepared me for white people. I wasn’t much of a talker anyway, but in Eau Claire you couldn’t pry my mouth open. It didn’t take much to tell that my way of talking was different than the way people talked in Wisconsin, and I felt freakish enough as it was…”

He then goes on to discuss his feelings about playing with and against mostly white ballplayers:

“…that…didn’t worry me as much as the idea of playing ball against white boys. I never doubted my ability, but when you hear all your life that you’re inferior, it makes you wonder if the other guys have something you’ve never seen before. If they do, I’m still looking for it. It didn’t take long to find that the ball was still round after it left a white pitcher’s hand, and it responded the same way when you hit it with a bat.”

Despite his culture shock at his new teammates, opponents and surroundings, Aaron’s bat was alive and he initially hit the ball well at Eau Claire. Perhaps because of the culture shock, however, he soon became very home sick, and for a while contemplated quitting baseball. Compounding his depression was an incident that occurred on the field, where in the process of turning a double play Hank’s throw to first hit the oncoming runner square in the forehead, knocking him out cold. The player had to be carried from the field on a stretcher, and Hank felt terrible about it. Fortunately, when he called to tell his parents he was coming home, his older brother Herbert Jr. took the phone and told him he’d be crazy to leave; that there was nothing for him back in Mobile; and that if he did leave he’d be walking out on the best break he ever had. Just as fortunately for all of us future baseball fans, Hank listened to his brother and stuck it out at Eau Claire. By mid-season he was leading the Northern league in hitting and was once again drawing scouts from the big club to check him out. One of these, a man named Billy Southworth, after watching Aaron play, filed a report stating, “For a baby-face kid of 18 years his playing ability is outstanding. I will see the remaining games but will send in the report now, ‘cause regardless of what happens tonight, it won’t change my mind in the least about this boy’s ability.”

For his excellent play with the Eau Claire Bears, Hank was voted to the Northern League All-Star team and at season’s end was named the league’s Rookie of the Year. Though the Eau Claire season was over, Hank would cap off his 1952 baseball year by temporarily returning to the Indianapolis Clowns and helping that team win the 1952 Negro League World Series over the Birmingham Black Barons. Unlike the Major League World Series, the Negro League Fall Classic was not a best of seven game series, but was best of thirteen. Also, the games weren’t split between the two team’s home ballparks; but were played at 13 different venues in different towns all throughout the South. The Black Barons had been leading the Series 5 games to 3, when the Clowns went on a streak, claiming 4 consecutive victories to take the Negro League championship for Indianapolis. In the Series Aaron once again displayed his superb hitting skills, batting over .400 while blasting 5 home runs. With the clinching game being played in New Orleans, it was only a trip of a couple of hours for Hank to return to Mobile to see his family. Once there he quickly found that his great success as a ball player changed nothing about his mother’s demands that he finish his high school education, and Aaron soon found himself back in school doing just that.

To be continued…

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2021 by Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Ed Clark and Bunny Downs were two of the influential figures in Hank Aaron’s early baseball career. Clark was the manager of the Mobile Black Bears, a semi-pro team Hank played for in Mobile before going to the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro League. He was also a part time scout for the Clowns. Downs was the business manager for the Clowns in the early ‘50s, and was the man who signed Aaron to his first professional baseball contract. For more on Clark and Downs please read Part I of this series.

[2] Albert Elliott “Buster” Haywood (1910-2000) was a Negro league baseball player. He played for the Clowns in both Indianapolis and Cincinnati, the Birmingham Black Barons, and the New York Cubans. At the end of his career he managed the Clowns and was Hank Aaron’s first professional manger.

[3] Wally Pipp (Walter Clement Pipp 1893-1965) was an American professional baseball player. A first baseman, Pipp played in Major League Baseball for the Detroit Tigers, New York Yankees, and Cincinnati Reds between 1913 and 1928. He is most famously known for losing his starting job at 1st base to Lou Gehrig after missing a game due being hit by a pitch in the head.

[4] Miller James Huggins (1878–1929) was an American baseball player and manager. Huggins played second base for the Cincinnati Reds (1904–1909) and St. Louis Cardinals (1910–1916). He managed the Cardinals (1913–1917) and New York Yankees (1918–1929), including the Murder’s Row teams of the 1920s that won six American League (AL) pennants and three World Series championships.

[5] Henry Louis Gehrig (1903-1941) was an American professional baseball first baseman who played 17 seasons in Major League Baseball for the New York Yankees. Gehrig was renowned for his prowess as a hitter and for his durability, which earned him his nickname “The Iron Horse”. After famously winning the Yankees 1st base job from Wally Pipp when Pipp sat a game with a headache, Gehrig went on to establish himself as one of the greatest players ever with a career .340 batting average, 493 HRs and nearly 2000 RBIs. His record streak of playing in 2,130 consecutive games lasted for 56 years, until broken by Cal Ripken in 1995.

[6] Buck O’Neil (1911-2006) was a first baseman and manager in the Negro American League, mostly with the Kansas City Monarchs. After his playing days, he worked as a scout, and became the first African American coach in Major League Baseball. Later in his life he was famously featured in the Ken Burns docu-series “Baseball”, for which he was interviewed by Burns several times.

[7] The Kansas City Monarchs were the longest-running franchise in the history of Negro League baseball. Operating out of Kansas City, Missouri, The Monarchs won ten league championships before integration, and triumphed in the first Negro League World Series in 1924. The Monarchs had only one season in which they did not have a winning record. The team produced more Major League players than any other Negro league franchise, including, of course, Jackie Robinson, who broke the Major League color barrier in 1947. The team was disbanded in 1965.

[8] Jack Roosevelt (Jackie) Robinson (1919-1972) was an American professional baseball player who became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball in the modern era. Robinson broke the baseball color line when he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. Signed by Brooklyn GM Branch Rickey the year before (1946) with the intention that he would be the first Black player brought to the Big leagues, Robinson had to endure a constant barrage of racist comments from opposing teams and fans, but the quality of his play eventually won the day, and opened the door for the many players of color to follow, including Hank Aaron.

[9] Wesley Branch Rickey (1881–1965) was an American baseball player and executive. He is most famous for his role in breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier when, as GM of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he signed a Black player, Jackie Robinson, to a contract with the Dodgers and brought him to the Majors in 1947. He also created the framework for the modern minor league farm system, encouraged the Major Leagues to add new teams through his involvement in the proposed Continental League. He also introduced the batting helmet into the game, to help protect the players. He was posthumously elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1967.

[10] Syd Pollock (1901 – 1968) was an American sports executive in Negro league baseball. He was associated with several clubs and leagues from 1926 to 1965, including as part and eventual primary owner of the Indianapolis Clowns from 1937 to 1965.

[11] John W. Mullen (1924 – 1991) was an American Major League Baseball executive from 1947 to 1991 with the Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves and the Houston Astros. Mullen served as the farm system director and head of minor league operations with the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves from 1960 to 1966. As noted in the article, he was the man, along with Dewey Griggs, who was responsible for signing Hank Aaron for the Braves. With Mullen’s long career as an executive with the Braves, when he passed suddenly in 1991, Braves manager Bobby Cox commented, “John had been with the Braves since their Boston days. No one has done more for the Braves than John Mullen. We’ll all miss him.” The Braves wore his initials, JWM, on the right sleeves of their jerseys during the 1991 season.

[12] Dewey Griggs (1899-1968) was a scout for the Boston Braves (1947-1952), Milwaukee Braves (1953-1959), and Philadelphia Phillies (1960-1966). Griggs signed Hank Aaron in 1952, and also discovered and/or signed players such as Johnny Logan and Wes Covington.

[13] Stating Aaron was 17 years old in his report was Griggs’ error. Hank was actually 18 at the time.

4 Responses

Love it!!

Thanks, Joline! Glad you liked the article! L Mark

I am a New Yorker that used to be a Brooklyn Dodger fan….Followed all of the players in both leagues and when the Dodgers announced they were moving to Los

Angeles, I decided to switch alliances. Liked the Milwaukee Braves roster, ESPECIALLY that kid with the great swing, Henry Louis Aaron…..He is my all time favorite player!!!!! Still in NY and still a Braves fan….Always wear my #44 HOF shirt which I got at the HOF in Cooperstown, many years ago…..

R.I.P. Hank!!!!

Thanks for commenting, Ken; and for sharing your story has a Braves and Hank Aaron fan. Many of us share your sentiments. Here in Seattle I was privileged to see Ken Griffey Jr. play with the Mariners for 10 seasons, as he went from a 19 year old kid to one of the greatest power hitters and players ever. I always thought that is what it must have been like watching Aaron develop as a player and hitter from his early years in Milwaukee and on to breaking Ruth’s HR record. What an awesome player he was! Best, Mark