Note: Presented here is Part III of the series I have written to acknowledge the remarkable career of the greatest Japanese baseball player to ever play in the Major Leagues–Ichiro Suzuki. The Seattle Mariners right fielder, who retired last week in the 8th inning of an M’s game against the Oakland A’s played in Tokyo, Japan, is a certain first-ballot Hall of Famer. Ichiro played most of his Major League career with the Mariners, was a 10 time All Star, a 10 time Gold Glove winner, won two AL batting titles, one AL MVP award; and in the 2004 season set the single season Major League hit record with 262 hits (the feat I chronicle in this series.) Along the way he accumulated more hits in professional baseball, between 9 seasons in Japan (1278) and 18 in the Majors (3089), than any player ever has. Truly, Ichiro Suzuki is one of the most unique and gifted players to ever play the game, and we may not see his like again…please read on…MA

In Honor of Ichiro-Part III

The winter of 2003-2004 the Mariners made major changes. Deciding he was too injury prone, they traded their talented short stop, Carlos Guillen, to the Tigers and brought in the older Rich Aurelia from San Francisco to take his place. Supposedly Aurelia was a better hitter with more power. They also signed Scott Speizio from the Angels for third base and brought back Raul Ibanez, who had become a budding star in Kansas City, to play left field. Mike Cameron and his league leading strike outs were sent to the Mets, which meant that Randy Winn would be our regular center fielder. The team figured they could get another year from John Olerud at first base, and Brett Boone was solid at second. The still reliable Dan Wilson was behind the plate; the pitching staff seemed sound, and they acquired a veteran closer, “Every Day” Eddie Guardado, from the Twins to replace Kazuhiro Sasaki, the closer for the prior 3 years who had opted to return to Japan. Of course, the beloved Edgar Martinez still DHd; the Ms were hoping for one more decent year from the old veteran.

The players the Mariners kept were all players they had won with, and the players they brought in all seemed like quality major leaguers. That being so, when the team got off to a terrible start in the 2004 season, no one saw it coming. After five games they were 0-5, they finished the first month with 8 wins and 15 losses; and things went downhill from there. Everyone on the team sucked, and all at the same time. At the end of April Ichiro was hitting .255. I lamented it, but my estimation of him based on Bill James seemed spot on. Except for his great defense, which I had discovered was not as important as offense, Ichiro was becoming ordinary to me.

For we Mariners fans, our only solace at the end of April was that things could not stay this bad. Wrong! By the end of May we were 19-31 and mired in last place; by mid-June we were out of the race. I couldn’t believe it. For Ichiro, however, something had begun to change. In May he had a 50 hit month, a rare feat by any measure. By month’s end his batting average had risen 80 points and his OBP (On Base Percentage) as well as slugging percentage, had risen by 70 points and 106 points respectively. Ichiro was starting to hit. While the Mariners were going south, our Japanese right fielder was starting to go north. He slumped a bit in June, but in July had a 51 hit month, with two 4 hit games and one 5 hit game. On August 3rd against the Orioles he had another 5 hit game. At that point his average had climbed above .350, his OBP was nearly .400, and he was leading the league in hitting. I began to realize, Bill James notwithstanding, that there was clearly something special happening here. Putting together 50 hit months and 5 hit games in the Big Leagues is not easy, as the rest of the Mariners team was proving with their futility.

The type of season being had by the rest of the Mariners is the kind of thing that makes you go in for superstition. Aurelia, the great hope at short, never came out of an extended season opening slump, and the Mariners finally let him go. Meanwhile, Carlos Guillen, the guy we got rid of for Aurelia, was having a career year with his new team, the Tigers. Hitting for average and power, he had become an All Star. Arsenic anyone? Speizio went into a slump the likes of which he had never seen in his entire career. Boone was hitting less than .240 and his homers and RBIs were way down. And Olerud? My God! You’d think a former batting champ could remember how to hit! The guy was terrible! The team finally opted to go with a youth movement and released him; the season being lost anyway. Olerud ended up catching on with the Yankees, and only then, of course, started to hit.

reliable, was hitting

barely .250…

Even Edgar Martinez, the old reliable, was hitting barely .250. It looked like age was having its way with ‘Gar. It was obvious to me that he could no longer handle the big sweeping curve balls he got from right handed pitchers. I got tired of watching him bail out on that pitch. Why would you ever throw him a fastball? It was sad to see. Our most reliable hitter in the first half, other than Ichiro, was Raul Ibanez. But he had gotten injured, of course, and missed a month with a bad hammy. Our new hitting coach, Paul Molitor, seemed overwhelmed by the situation. He certainly did nothing to correct it.

The pitching was not much better. Soft-tossing Jamie Moyer hadn’t won in months, and led the league in homers allowed. The talented, but puzzling, Gil Meche had been sent down to get his head straight in the minors, and another starter, Ryan Franklin, had something like 2 wins against 10 losses. Our new closer, Eddie Guardado, didn’t get much work due to the infrequent save opportunities, and when he did pitch he seemed to be pressing; not nearly as effective as he was with the Twins. Finally, he was found to have a shoulder problem and was shut down for the year. The young players the Mariners brought up were fun to watch, but didn’t make up for the terrible season. Bo Mel (M’s manager Bob Melvin) just seemed impotent to do anything about it—he had no fire in his belly it seemed. Lou would have kicked some ass. (As I said earlier, I miss the passion Lou brought to the park.) It’s a good thing I am not the dour sort. If you were, this was the sort of season you might not ever recover from. You might become an alcoholic or a drug addict. I began to adapt the lyrics to Steve Goodman’s song about the dying Cub fan so it would fit the Mariners. Things were that bad.

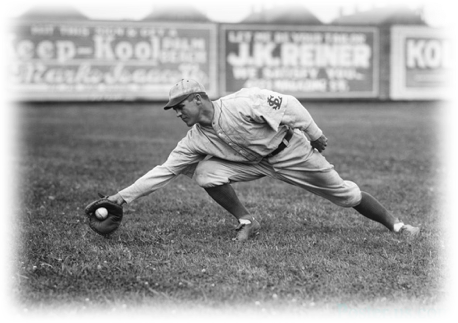

By the first week of August there was one bright spot for the Mariners, however, and that was Ichiro. After that August 3rd 5-hit game against the Orioles I began to wonder; just what was the record for hits in a season in the Major Leagues? I didn’t have to wait long to find out. Within a couple of weeks Ichiro had had 2 more 4 hit games and was well on his way to another 50-hit month. The papers were starting to talk about a guy named George Sisler. In 1920 he had set the still standing Major League record with 257 hits for the season. In the 84 years since no one had ever surpassed it. That’s longer than Babe Ruth held the Home Runs in a season record, and longer than Joe DiMaggio has held the hitting streak record! 84 years—that’s a long time! Who was this guy, George Sisler? I decided I would make it my business to find out. So, I turned back the hands of time and lost myself in the mists of baseball history.

helluva ballplayer

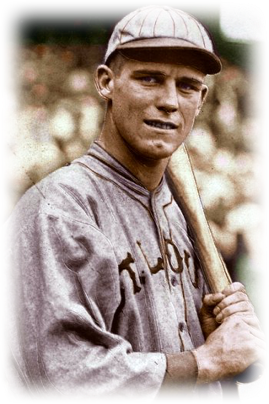

I discovered that George Sisler was a helluva ballplayer. So good in fact, that Ty Cobb, the “Georgia Peach”, had once said of him: “Sisler could do everything. He could hit, run and throw, and he wasn’t a bad pitcher either. He was the nearest thing to a perfect ballplayer.” That’s high praise when you consider the source. His nickname was “Gorgeous George” due to the graceful way he played first base, which was his position for most of his career. Born in Manchester, Ohio on March 24, 1893, Sisler signed a contract at 17 to play with a minor league team in Akron, Ohio, but received no money. Eventually he opted to go to college instead, and attended the University of Michigan, where he played for none other than the legendary Branch Rickey.

They forever changed the game…

and the country

Rickey, of course, was one of the most colorful and influential characters in the history of baseball. From the University of Michigan, Rickey went on to become part owner and manager of the old Saint Louis Browns. Later, when he was with the Saint Louis Cardinals, he revolutionized the game with his development of the minor league farm system, which turned the Cardinals into perennial contenders. Most significantly, however, Branch Rickey was the guy who, as GM of the Brooklyn Dodgers, broke the color barrier by bringing Jackie Robinson to the Major Leagues. A religious man, Rickey was deeply motivated by an experience he had as a college coach, when one of his players, a black man, was not allowed to stay in the same hotel as the rest of the team. Rickey later found the player in a despondent condition, wishing he could tear off his black skin. The incident deeply affected Rickey and he vowed to someday do something about it. That day came when, due to Branch Rickey’s efforts, Jackie Robinson walked out onto Ebbets Field and took his position to open the 1947 season. A black man, at last, was playing in the Major Leagues. Rickey, again, had forever changed the game; and in so doing had forever changed the country.

When Sisler graduated from college he received a telegram from Rickey asking him to come and play for the Browns. That old contract he had signed at 17, however, very nearly stopped his Browns career before it started. The Akron minor league team had sold the contract to another minor league team, which in turn had sold it to the Pittsburgh Pirates; and the Pirates were claiming the contract was still valid. A three-man commission was appointed to determine if Sisler would go to the Browns or would become Pirates property. They ruled in favor of Rickey and the Browns, so Sisler went to St Louis, where he would play for the next 13 years, from 1915 to 1928.

Sislerset his hit record…

It was in the 1920 season that Sisler set his hit record, playing every inning of all 154 games that season. Besides the 257 hits that year, he also had a .407 batting average, scored 137 runs, drove in 122, and stole 42 bases. Jesus! Could this guy play or what!! On top of that, Sisler had been a pitcher in college, and no doubt could have been a successful Big League pitcher. His first few years with the Browns he pitched from time to time, twice defeating Hall of Fame legend Walter Johnson with complete game victories, one of which was a 1-0 shutout. By 1919, however, he was being used exclusively at first base, and is arguably one of the greatest first basemen who ever lived. Though very fast and an excellent fielder; it was as a hitter that Sisler excelled. He hit better than .400 twice in his career, the second time being 1922 when he hit .420 to win the batting title. That year Ty Cobb came in second with a .401 average—only the second time in history that a player hit .400 and did not win the title. It was Sisler who set the AL hitting streak record of 41 games, which stood until Joe DiMaggio broke it with his incredible 56 game streak in 1941. He hit .340 for his career, while accumulating over 2800 hits. Yes, George Sisler could play, no doubt about that. Bill James analyzed him statistically and concluded, “He is probably the only player other than Gehrig who can reasonably be considered the greatest first baseman ever in terms of peak value.” Sisler was voted into the Hall of Fame in 1939.

but there, still visible, was the

name, Dick Sisler…

As I studied the history of George Sisler, I discovered that two of his sons, Dick and Dave, had fashioned Major League careers for themselves. When I read this it gave me pause; the name “Dick Sisler” resonated in my mind—what was it about that name? And then I remembered—an old ball a friend had given me a few years earlier; musty smelling and discolored, it had been in storage for many years. At some point in the 1950s it had been signed by the whole Seattle Rainiers AAA baseball team. I got the ball out and looked it over. The ink was now old and faded, but there, still visible, was the name “Dick Sisler,” clearly written on the old horsehide. I Dimly recalled him as the Rainiers manager in those days. Rolling the ball in my hand, I pondered the history I was now holding—I felt a strong connection with the past. After a few moments, I put the ball back in its case.

George Sisler died on March 26, 1973. He was 80 years old.

Seven months later, on October 22nd, 1973, in Kasugai, Japan, Ichiro Suzuki was born.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2019

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved