Note: Presented here is Part V of the series I have been researching and writing on the Bank for International Settlements. The title of this installment is “The BIS Enters World War II.” As with all prior installments, since the later installments presume an understanding of the material in the earlier installments, it is best to read the series in sequence, starting with the Introduction and then continuing with Parts I, II, III and so on. All of the earlier installments can be found at my website fromanativeson.com in the “Politics” category and in the Archives. The BIS today sits at the apex of the world central banking system, yet it is not under the control of any nation or subject to any nation’s laws and is privately owned by the member central banks of the world, most of which are, in turn, privately owned. It exerts vast influence on the world banking system, yet its meetings are private and what is discussed in them is closely guarded. The whole purpose of this series is to enlighten the reader on just what the BIS is, how it got started and developed through the years, and to what use it has been put. My hope is that with this added understanding of the factors affecting us all we will be able to chart a better course for our future. With that understood, here is “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements–Part V: The BIS Enters World War II” I hope you enjoy it and learn from it. MA

The BIS Enters World War II

In the wake of “Kristallnacht” and the German takeover of Austria and the Sudetenland, Hjalmar Schacht’s days as Reichsbank president and BIS board member were numbered. From the mid 1930s on he found himself increasingly disagreeing with Hitler’s expanding government armaments spending and he also had come into conflict with Herman Göring,[1] whom Hitler had appointed as “Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan” [2] in 1936. Many of the powers granted to Göring under the Four Year plan conflicted with Schacht’s authority as Reichsbank President, Economics Minister and Plenipotentiary of the War Economy; posts he had held since 1933 (as Reichsbank President) and 1934. In addition, it was becoming obvious even to Schacht that in helping Hitler to rebuild Germany and the Nazi war machine he had sold his soul. Though to this point he had used his power very willingly to help restore the German military and re-arm the nation, he now saw that continued armaments spending, which Hitler was planning on expanding, posed a very real threat of inflation and resultant economic meltdown. Much of the country’s gold and foreign exchange reserves had now been spent on the re-armament campaign. Other debts, such as the redemption of the $12 billion worth of MEFO bills[3] that had been floated to help fund the rearmament, were now coming due and there was insufficient revenue to pay them. Over the prior five years the German money supply had tripled and now Hitler was planning far more spending. It was obvious to Schacht that his Führer knew nothing of economics.

Moreover, the Reichsbank president had never joined the Nazi Party and did not believe in their racial superiority theories and polices, particularly as regards the Jews. The destruction and murder of “Kristallnacht” had driven this home to him to the point that at the Reichsbank Christmas party a few weeks later he stated in a speech to his staff that the attacks on the German Jews were, “such a wanton and outrageous undertaking as to make every decent German blush for shame. I hope none among you had any share in these goings-on. If any one of you did take part, I advise him to get out of the Reichsbank as quickly as possible. We have no room in the Reichsbank for people who do not respect the life, the property and the convictions of others.” [4]

As you might surmise, speaking that way in Nazi Germany in December of 1938 meant that Schacht was walking a very thin line. Politically he was a nationalist and pro-business German who hated the fact that the Treaty of Versailles following World War I, with the restrictions and reparations it imposed, had relegated his nation to second class status and economic ruin. As with many Germans of his class, Hitler’s talk of returning Germany to glory and prosperity resonated with him. The compromise that he and other prominent Germans made was that in going along with the Nazis they also tolerated the outrages perpetrated by them, thus making them guilty too. Schacht’s situation calls to mind a great scene in the movie “Judgment at Nuremberg” that illustrates this. (If you have never seen this movie I urge you to watch it.) The movie is a fictionalized account of the actual American war crimes trial of the German judges who had responsibility for implementing the repressive Nazi race laws targeting the Jews and other minorities. One of these German judges was an internationally respected jurist by the name of Ernst Janning [5], who had helped to establish the German Weimar Republic and its Constitution right after World War I. As one of the senior jurists in his nation, Janning had perhaps more responsibility than others of his profession for the rise of the Nazis and the degradation of human rights in Germany that followed. Had he and others of his stature not gone along with Hitler and had refused sign their loyalty oaths to him, as all German judges were required to do, a strong argument can be made that they could have stopped much of the Nazi program before it really got rolling.

But the judges did go along with the Nazis, and the consequences have pinned the responsibility to them almost as much as to Hitler and his major henchmen themselves. In the character of Ernst Janning, as portrayed by Burt Lancaster in the movie, that responsibility is graphically and keenly felt in a climactic scene on the witness stand, when, after describing the crimes and moral failings of three of his co-defendants, he states in scathing self-recrimination, “…and Ernst Janning…worse than any of them; because he knew what they were, and he went along with them. Ernst Janning—who made his life excrement—because he walked with them.”

Of course, there is no way of knowing how Schacht actually felt; and as you can see from all of the information about him in this series, the man had a rather large Machiavellian streak of his own. Without his genius the Nazi war machine would not have been built so rapidly, and who knows how that would have affected the war that was to come. Possibly it would not have happened at all. What is certain, however, is that by the early weeks of 1939 he had fallen into disfavor with the Führer. By then Hitler had already removed him from his other posts in the government—Economics Minister in 1937 and Plenipotentiary for the War Economy in 1938. Likely the final straw for Hitler regarding Schacht occurred in early January, 1939, when the Reichsbank president and 7 other Reichsbank board members all signed a memo to the Führer which stated, “The reckless expenditure of the Reich represents a most serious threat to the currency. The tremendous increase in such expenditure foils every attempt to draw up a regular budget; it is driving the finances of the country to the brink of a run despite a great tightening of the tax screw, and by the same token it undermines the Reichsbank and the currency.” [6]

A couple weeks later, on 20 January, 1939, Schacht was summoned to Berlin by Hitler and informed that he was being removed from his position as Reichsbank president; which, by default, removed him from the BIS board as well. While he was retained as a minister without portfolio[7] by the German government until 1943, with his ouster from the Reichsbank presidency and BIS board, Schacht’s meaningful role in the BIS and Nazi Germany economics and banking came to an end. Following the failed assassination attempt on Hitler in July of 1944 [8], which he very likely had little or nothing to do with, Schacht was arrested and spent the rest of the war in a series of Nazi concentration camps. [9]

Hitler’s choice for replacing Schacht as Reichsbank president was the same man he chose earlier to replace him as Economics Minister and Plenipotentiary of the War Economy, a 48 year old former journalist named Walther Funk. As a result Funk also inherited Schacht’s position on the board of the Bank for International Settlements. Funk, by some accounts a man of loose morals in his personal life; was, nevertheless, a dedicated Nazi. He joined the party in 1931 and in the years following became one of Hitler’s key economic advisors.[10] According to Adam Lebor in his book “The Tower of Basel”, Funk played a major role in helping German big business and industrialists, including the giant chemical cartel IG Farben, to funnel money to the Nazis. Likely, with Hitler already planning what would be his assault on Europe (which would commence with the invasion of Poland in September of 1939, 8 months later) a man was needed to run the Reichsbank and in the BIS who would be absolutely subservient to Nazi goals, which Hitler knew Schacht wasn’t. Walther Funk was, and under his watch and in these roles the economic plans were made for the subjugation of Europe under the Nazi thumb, starting with Poland, and later France and the Soviet Union.

Besides Schacht’s removal from the board, the early months of 1939 brought more change to the BIS. Around the same time Schacht was replaced on the board another man who had been on the BIS board since the bank’s founding, an influential German businessman named Paul Reusch, [11]resigned. This afforded Walther Funk the opportunity to hand pick Reusch’s successor to the board, and he selected none other than Herman Schmitz, the 58-year-old CEO of the soon to be infamous giant German chemical cartel IG Farben. [12] In May of that year, with the incumbent president Johan Beyen (the same man who had approved the infamous Nazi rip-off of the Czech gold, which launched the biggest PR flap in the BIS’ short history) set to retire in 1940 the BIS board undertook the task of finding the bank’s next president. Of the short list of candidates considered, the most favored was a 50 year old American attorney by the name of Thomas McKittrick. Though he had no direct experience in central banking there were other factors that recommended McKittrick for the job. First, he was an American; and in 1939, with war obviously coming in Europe, the United States was still a neutral country. All BIS members were in agreement that in the event of war the bank should remain open and functioning to retain the international financial channels that had been developed; and that the man selected for the job should therefore come from a neutral country and not a belligerent one.

Second, while his central banking experience was limited, McKittrick had established himself in the financial world both before and after World War I. After graduating from Harvard in 1911 he took a job working for National City Bank of New York at their foreign office in Italy. With the U.S. entry into World War I he joined the Army and was stationed in Liverpool where he received intelligence training and experience from the British as a result of being assigned the task of ensuring that no spies were infiltrating through English ports. Following the war he returned to the U.S. and in 1919 went to work for Boston based Lee, Higginson and Company, then one of the premier investment banks in the world. In 1921, because of his European experience both before and during the war, he was sent to London to work for the company’s English branch. There he flourished and over the next few years, as Adam Lebor reports, McKittrick “built up an impressive network of contacts with international connections.” Lee, Higginson soon promoted him to partner status and in that capacity he ran their foreign operations in both London and New York. During this period, the mid 1920s, he spent much time working on the various German loans and investments that resulted from the Dawes Plan, which in turn brought him into contact with the ubiquitous John Foster Dulles, the Sullivan and Cromwell attorney who handled many of these loans and bonds for his company’s American and European clients. McKittrick became so accustomed to his life in London during those years that in recalling them later he stated, “I was leading the life of an Englishman. My associates were all British, and toward the end of that time I was frequently spoken to by people who assumed I was British.” His large array of connections and thorough familiarity with Britain and Europe, as well as his country’s neutrality, made McKittrick appear ideal for the post of BIS President.

In addition to all this there was a third factor recommending McKittrick, and that was the fact that he had already worked for the BIS as part of the German Credits Arbitration Committee in 1931; a group which, as part of the BIS role in administering reparations payments and Young Plan loans, worked to resolve any disputes arising with or between German banks. It was in that role that he became acquainted and worked with another of Europe’s leading bankers of the day, Marcus Wallenberg, who with his brother Jacob ran Sweden’s Enskilda Bank. The Wallenberg brothers were well connected to financial circles in New York, London and Berlin and would soon use those connections, knowledge and Swedish neutrality to make vast profits during World War II through dealing with both sides—the Nazis and the Allies. [13] In 1931 Marcus was also on the Credits Arbitration Committee and from him McKittrick learned much about the ways of international banking, which the Wallenbergs were masters of.

Thus, in May of 1939 Thomas McKittrick was formally offered the post of president of the Bank for International Settlements at a salary of $40,000 per year (nearly $700,000 today). He accepted the offer immediately and started making plans for the move from London to Basel. His first actions in his new job were taken prior to assuming post and consisted of travelling to the various European central banks to meet the BIS directors and bankers. Upon returning to London, before he could even make the move to Basel, he was contacted by attorneys representing a most unusual client: Hitler’s former public relations chief Ernst Hanfstaengl, who had fled from Germany to England after falling into disfavor with the Führer and was being held in custody in London as an enemy alien. Hanfstaengl is another of those fascinating characters, like Hjalmar Schacht and Rudolph Hess, who seemed to gravitate around Hitler and the Nazis and had amazing stories to tell. In Hanfstaengl’s case, he was born in Munich of a German father and an American mother, attended and graduated from Harvard University in 1909 and later ran his father’s fine arts publishing business in New York. Along the way he became acquainted with, among others, Walter Lippman, Charlie Chaplin, William Randolph Hearst and future and former presidents Franklin and Theodore Roosevelt. In the early 1920s Hanfstaengl moved back to Germany and became enamored with Hitler after seeing him speak in a beer hall meeting. He introduced himself to the future Führer and because of his high society connections on both sides of the Atlantic and his fluent English ultimately became chief of the Nazi Foreign Press Bureau in Berlin. It was likely because their client and McKittrick shared many of the same high society connections that Hanfstaengl’s attorneys asked the American banker for a character reference, even though McKittrick and Hanfstaengl had never met. Nevertheless, McKittrick complied with the request and Hanfstaengl was ultimately released and sent to the United States, where he compiled psychological profiles on Hitler and other top Nazi’s for the OSS. [14]

On September 1st, 1939, after the Nazis secured a mutual non-aggression pact with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union stipulating that the two nations would divide Poland, World War II began in earnest when Hitler launched his invasion of Germany’s eastern neighbor. Though the invasion was cloaked with the by now standard Nazi “false flag” [15]claims of Polish abuse of German nationals and initiation of border skirmishes, it was obvious to all that this was another case, the most blatant yet, of wanton German aggression. Pledges received from England and France earlier meant that both of those nations would now come to Poland’s aid; which they did just two days later, on September 3rd, by declaring war on Germany. With the Japanese already fighting China in Asia, and soon to engage the French and British in Southeast Asia, the war was now global. Before it was through over 30 nations would be involved and, counting famine and disease related fatalities, over 80 million people killed, making World War II by far the deadliest conflict in history.

As noted earlier in this article the BIS directors had already determined that in the event of war the bank would remain open to carry out its functions as well as it could under the circumstances. The directors were casting an eye toward the post war future and wanted to ensure the BIS would be there and play a role in the reconstruction of Europe after the war. They also unanimously agreed that the bank would follow a policy of neutrality for the duration of the war, and Thomas McKittrick, as the new BIS president, promised as much when he issued a formal statement to the Swiss government stating that no BIS staff would, “undertake political activities of any sort whatsoever on behalf of any governments or national organizations.” According to Adam Lebor in his book “Tower of Basel” what this neutrality declaration meant was that, “the bank would not grant credit to central banks of belligerent countries; it would, when operating on neutral markets, ensure that belligerents did not profit from such transactions; it would not carry out any transactions, either direct or indirect, between countries at war with each other; it would not sell assets in one country to make a payment to another if they are at war; and it would not hold assets of one belligerent country secured against another.”

Despite McKittrick’s high sounding words and pledge of BIS neutrality it soon became apparent that his promise was not worth the paper it was printed on. As Lebor states in his book, “McKittrick and the rest of the bank’s management turned the BIS into a de facto arm of the Reichsbank.” Throughout the war the BIS carried out foreign exchange transactions with the Reichsbank, and right up to the war’s end accepted Nazi gold looted from the countries and peoples of Europe. As Nazi Germany went about the process of invading and occupying countries such as France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Greece and others and forcibly incorporated them into the Third Reich, their actions were legitimized by the BIS by its acceptance and acknowledgement of the takeovers. The BIS ownership shares of these subjugated nations were allowed to transfer to the new Nazi controlled governments with the result that at its peak over 67% of the BIS shares were controlled by the Nazis and their allies.

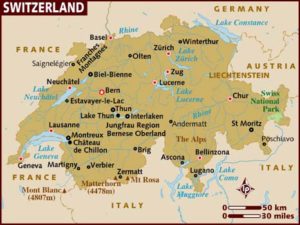

If you have ever wondered, as I have, why it is that Hitler’s Germany did not invade and take over Switzerland during World War II, as they did the rest of Europe, in the above you likely have your answer. For a while, as France was being overrun by the Germans in May/June of 1940, Swiss authorities greatly feared there would be a Nazi invasion of their nation and made plans to evacuate the BIS home town of Basel, which at the time was enclosed on the north, east and west by German controlled territory. Thomas McKittrick himself made plans to flee the nation and did, in fact, flee from Basel to the town of Bern, which was to the south of Basel in the center of the country. A short while later he and the BIS relocated to the town of Chateau d’Oex in southwestern Switzerland; but the anticipated Nazi invasion never took place, and by October of 1940 the bank and its operations were back in Basel. The simple truth is that the BIS, with all of its international banking connections and communication lines, its value as a gold receipt and exchange agent, as well as its potential as a source of financial intelligence on its member nations, was far more valuable to the Nazis than the small, mountainous country of Switzerland would ever have been. Add in the fact that the Swiss franc, of all the currencies of Europe at the time, was the most valued and accepted in foreign exchange transactions, and you can see that the Nazis had little to gain and much to lose by occupying Switzerland.

And so, by the end of 1940, as Europe and the world were being engulfed in war for the second time in a generation, the Bank for International Settlements was back in Basel and functioning, relatively safe from the conflagration consuming the rest of Europe. It would survive the war intact…but, as we shall see, not without some challenges.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2017

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Herman Göring (1893-1946) was a German World War I fighter pilot ace and a very early Nazi Party member and supporter of Adolf Hitler. For much of the time Hitler was in power he was the second most powerful man in Germany. In 1933 he founded the Gestapo and later turned over command of that secret police organization to Heinrich Himmler. In 1935 he was made the Commander of the German air force, the Luftwaffe, a post he held throughout most of World War II. By mid 1943, however, with increased battlefield reversals and Hitler’s perceived Luftwaffe failures to protect his armies on the eastern front and to stop the Allied bombing of German cities, Göring’s standing with the Führer began to slip; and he spent much of his time towards the war’s end trying to accumulate as much stolen wealth and as many stolen art works to himself as possible. In April of 1945 he heard of Hitler’s plans to commit suicide, and sent him a telegram asking to be appointed as his successor. Upon receipt of the telegram Hitler was furious. He considered Göring’s request an act of treason, expelled him from the Nazi Party and ordered his arrest. With Germany’s collapse, a few weeks later Göring was arrested by the Allies. He was charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity, was tried at the Nuremberg trials, was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging; a sentence that was never carried out. On October 15, 1946 Herman Göring committed suicide by taking cyanide.

[2] The “Four Year Plan” adopted by Hitler and the Nazis in 1936 was a series of economic measures designed to provide for the rearmament of Germany and to make the country self-sufficient within 4 years; i.e. by 1940, the overall purpose being to prepare the nation fully for the war Hitler intended and knew would be coming.

[3] For a full description of MEFO Bills please see Part IV of this series.

[4] Quoted from “Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe’s Bullion” by George M. Taber

[5] The Nuremberg Trials (1945-1949) were a series of trials of the German Nazi leadership that took place after the end of World War II in Nuremberg, Germany. The most high-profile of the trials occurred in the initial stage, running from 1945 to 1946 and targeting top Nazi officials for their participation in war crimes. The events in the movie Judgment at Nuremberg were based on the 1947 “Judges’ Trial,” in which 16 German judges, lawyers and officials tied to the Nazi Party were tried. The character of Ernst Janning was loosely based on Franz Schlegelberger, the highest-ranking defendant in the Judges’ Trial. Schlegelberger’s defense partially was based on the claim that by staying on his post he was at least able to mitigate some of the destruction and injustice wrought by the Nazi “legal” system. The hearings were presided over by a tribunal of three American judges, and after nine months 10 of the defendants were found guilty with four receiving life sentences. By the time the film was released in 1961 all of the defendants who’d been convicted had already been released from prison — including the four who received life in prison.

[6] Quote taken from “Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe’s Bullion” by George M. Taber

[7] A “minister without portfolio” is a government official who is without an assigned area of responsibility. In Hjalmar Schacht’s case, because of his reputation as the savior of the German economy, after he was fired from the Reichsbank Hitler kept him as a “minister without portfolio” for PR reasons.

[8] Of the numerous attempts that were made on Hitler’s life after he took power in 1933 (over 20), the one that was the most serious and came the closest to success took place on July 20, 1944 at the Führer’s field headquarters in East Prussia, a secured location known as the “Wolf’s Lair.” The plot was led by a man named Claus von Stauffenberg, who was a lieutenant colonel in the German Army, and involved a number of other high ranking German military officers and political leaders. The plan was to kill Hitler by means of planting a bomb in the meeting room of the Wolf’s Lair while he was involved in a strategy session. Once Hitler was dead the second part of the plan, called Operation Valkyrie, was to swing into effect to carry out a coup d’état to replace the Nazi regime with one that would enter into peace negotiations with the Allies and end the war. While von Stauffenberg was able to successfully place the bomb (which was in a briefcase) in the meeting room, the resulting explosion only shook Hitler up and did not kill him. Assuming Hitler was dead the coup was launched in Berlin, but when it was discovered that he was still alive SS troops loyal to him quickly brought the uprising to an end. In the wake of the failed coup von Stauffenberg, along with his co-conspirators and nearly 5,000 others, were arrested and executed. The war would drag on for 9 more months, finally ending in early May,1945, following Hitler’s suicide and the fall of Berlin.

[9] Towards the end of April, 1945, with Allied forces advancing into Germany from every direction, Schacht, along with a number of other high profile prisoners, was transferred by the SS to a supposedly more secure location in Tyrol, Austria, from which he was liberated on May 5th, 1945 by the U.S. Army. Shortly thereafter he was arrested again, this time by the Allies, and charged with “crimes against peace” due to his support of Hitler and his role in building up the Nazi war machine. He pled not guilty to the charges, was tried at Nuremberg and ultimately was acquitted, mostly due to the influence of the British judges who overrode the efforts of their Soviet counterparts to convict. (If you have read this series you know that Schacht had powerful allies in the Bank of England and other British financial circles) Following his acquittal Schacht reestablished himself by founding his own bank, Deutsche Außenhandelsbank Schacht & Co., which he ran for 10 years until 1963; and he also did economic consulting to heads of state of developing nations. He died in Munich, Germany on June 3rd, 1970, thus ending one of the more remarkable lives of the twentieth century.

[10] In his book “Chasing the Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe’s Bullion” author George Taber states, “Funk, according to Albert Speer (Hitler’s architect), had a reputation for a ‘dissolute love life.’ Schacht said Funk had been dismissed at the business paper because he was homosexual. Speer also claimed that the SS had a detailed dossier on Funk and had blackmailed him.” The Nazis, of course, frowned on homosexuality and being gay in those days in Germany was a sure ticket to a concentration camp. Very likely the SS blackmail of Funk took advantage of this and ensured his Nazi loyalty.

[11] Paul Reusch (b 9 Feb, 1868- d 21 Dec 1956) was a prominent German businessman who was the long term president (1909-1942) and chairman of the board of Guthoffnungshütte, a large, Ruhr based mining and mineralogical corporation, to which Reusch successfully added the production of machinery as an additional product. Politically he was a conservative German nationalist, opposed to the Weimar Republic, who flirted with the Nazi party and the support of Hitler in his efforts to gain power in the early 1930s. He never made a full commitment to Hitler, however, and as the Nazi party took full power through the 30’s and on into the war years he became more openly critical of them. In 1942 he was forced by the Nazis to step down from his position as chief of Guthoffnungshütte, and towards the end of the war conducted a discussion group called the Reusch Circle, composed of prominent German finance, industrial and agricultural men, including Hjalmar Schacht and Fritz Thyssen. The group did apparently have contact with some of the German resistance movements at the time, but no active involvement in plots against the Nazis that I have been able to find.

[12] IG Farben, which is short for “Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farbenindustrie” (meaning “Association of Common Interests of Dye-making Corporations”) was a huge German chemical company in the 1930s, and by the beginning of World War II was the largest chemical company in the world. Formed in 1926 by the merger of a number of German chemical companies, including Bayer and BASF, IG Farben very rapidly became the chief producer for the German war machine of vital chemicals, synthetic rubber, plastics, gunpowder, explosives, lubricating oil, aviation fuel, and even the Zyklon B poison gas used to exterminate the Jews and other people considered undesirable by the Nazis. The company also became notorious for its establishment of a factory next to the Auschwitz concentration camp which made full use of the slave labor provided by the camp. Farben was international in scope with an American subsidiary (American I.G.), which by World War II had been merged with another company and became known as “General Aniline and Film.” Following the war 24 of IG Farben’s directors were indicted for war crimes and 13 were sentenced to prison terms after being found guilty at the Nuremberg trials in 1947-48.

[13] Not every member of the Wallenberg family was as mercenary as Jacob and Marcus. In researching the Wallenbergs you don’t have to dig very deep before you encounter the remarkable story of a younger cousin or nephew of the brothers named Raoul Wallenberg. In 1944, while serving as the Swedish emissary to Budapest, he used his authority and courage to save tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from certain death at the hands of the Nazis. At the time the Nazi mass murderer Adolf Eichman and his henchmen had launched a program to deport all of the Hungarian Jews to concentration camps in Germany and Poland for extermination. By the time Raoul arrived in Budapest in the summer of 1944 hundreds of thousands had already been sent. Using his diplomatic authority and bribes he did his best to save the rest. One of the ways he did this was by issuing “protective passports” to the Jews which identified them as Swedish subjects who were waiting to be sent back to Sweden. This action stalled the Nazis and prevented many Jews from being sent to death. To house the Jews while waiting he rented 32 buildings in Budapest and declared them to be protected by diplomatic immunity, and thus outside Nazi controlled territory and laws. These buildings eventually housed and saved over 10,000 Jews. In 1945, shortly before the end of the war, he saved another 70,000 Jews, basically all that remained in Budapest, through direct negotiation with Eichman and the German commander in Hungary, convincing them that he would have them tried for war crimes after the war if they went ahead with plans to kill the Jews. A little while later the Russian army liberated Budapest and Hungary, but for some reason felt the need to arrest Raoul. What happened to him after is a matter of speculation and mystery. Some reports state he died later in 1945, and some state that he was executed in 1947 in a Russian prison. Still other reports state that he had been seen and spoken to in Russian prisons up into the 1960s. He was finally declared dead by the Swedish tax agency in October, 2016. For his efforts at saving the Hungarian Jews during World War II Raoul Wallenberg has been honored in memorials and monuments all over the world. Israel has bestowed its “Righteous Among Nations” honor upon him, and in 1981 US Congressman Tom Lantos, who himself was saved by Raoul and lived in one of his buildings in Budapest in 1944, sponsored a bill to make Wallenberg an Honorary Citizen of the United States. The life of Raoul Wallenberg stands as an example for us all of what one man can do in the face of injustice, suppression and intolerance. We should all have that kind of courage.

[14] OSS is the acronym for “Office of Strategic Services,” the US Intelligence agency established in World War II by President Roosevelt and William “Wild Bill” Donovan. Its personnel included Allen Dulles (who was the OSS station chief in Bern, Switzerland) as well as a number of others who would become key personnel for the CIA when it was created in 1947 by the National Security Act. President Truman disbanded the OSS after the end of World War II.

[15] A “false flag” incident or operation is simply one in which one government or group stages a false attack on or makes a false claim of abuse of its own people or territory, the purpose of which is to then blame another nation or group for the attack in order to justify an attack on that nation or group. It is an old intelligence trick.

4 Responses

great and well researched article and i enjoyed myself a great

Thank you for the kind words! MA

Hi Mark, great stuff. I’ve written my Master thesis about Schacht. It would be great to talk to you about this history. Let me know!

Hi Jay! Thanks for the nice comment. If you’ve done a Master thesis on Schacht you probably have done more thorough research on him than I, and I would enjoy getting your perspective of him from your research. From what I do know he was an economic genius, but got in over his head with Hitler and the NAZIs. I will send you an email at the address you provided and we can exchange views. Thanks again! My Best, mark