Note: Presented here is Part III of “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements,” entitled “Adolf Hitler and Two Bankers.” The earlier installments of this series, starting with the Introduction and continuing through Parts I and II, have covered the history that led up to the Bank’s creation, when it was created, who created it and the reasons why. Much of Part III is devoted to providing the reader with an understanding of how Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 and how two of the most powerful bankers in Nazi Germany came to be members of the BIS Board of Directors. To understand the role the BIS would play as Europe and the world were being drawn into World War II, this is essential information. As noted in the earlier parts, much of the material in this installment is drawn from Adam Lebor’s excellent book, “The Tower of Basel-The Shadow History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World,” as well as my own research. Should the reader wish to procure Lebor’s book I have included its Amazon link at the end of this article. To ensure full understanding this series should be read in sequence, with the Introduction and Parts I and II completed before tackling Part III. I have included links to the earlier installments here:

With that understood, here is Part III of “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements–Part III.” I hope you enjoy it. Please read on…MA

Adolf Hitler and Two Bankers

As the treaty of Versailles ending World War I was being negotiated in 1919 the government of Germany was undergoing a sea change. Immediately following the German capitulation to the Allies in November of 1918 a social revolution took place in the country that ousted the old aristocratic class along with the Kaiser (“Kaiser” is German for “Emperor”) and imperial form of government and replaced it with a new constitution. The result was a democratic republic that became known as the “Weimar Republic”, due to the fact that the new constitution was drafted in the German city of Weimar; an important cultural center, not just for Germany, but for all of Europe. The Weimar Republic was officially established on 11 August, 1919 and was beset from the start by all of the economic troubles thoroughly described earlier in this series. As a result two main groups emerged in Germany, both vying to wrest control of the country from the predominant Social Democratic Party. These two groups were the Communist Party and the National Socialist (Nazi) Party. By 1930 both of these parties were making significant gains, claiming a number of seats in the Reichstag (the German Parliament).

It was also in 1919 that a 30 year old, Austrian born World War I veteran named Adolf Hitler joined a new political party known as the German Workers Party, which by 1923 had morphed into the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP (meaning National Socialist German Workers, or Nazi, Party). In that same year of 1923, Hitler, who by then was leading the Nazis, staged a coup in Munich in an effort to overthrow the government of the German state of Bavaria. The coup failed and Hitler was imprisoned, during which time he dictated the first volume of his autobiography and political manifesto, “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle). The book, which was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926 and sold nearly a quarter million copies across the next 5 years, revealed the author’s plans for reshaping German society based on race and implied the elimination of undesirables; chiefly the Jewish people and Communists, whom he blamed for the bulk of Germany’s woes. Hitler was released from prison in December, 1924 when his 5 year prison sentence was commuted to time served. As a condition of his release he had to agree that he would seek power only through legal, democratic means; and so over the next several years he concentrated on organizing and growing the Nazi party.

Through the middle of the 1920s, as a result of the Dawes Plan loans and the foreign investment in the country, the German economy improved; but that all changed with the stock market crash of 1929. As a result of the crash the German economy plunged into depression and millions of people lost their jobs. Using a platform of promising to strengthen the economy to provide jobs and repudiating the Versailles treaty and reparations, which most Germans hated, Hitler and the Nazis were primed to rake full advantage. By early 1932 they had gained enough power that Hitler ran for president of the nation against the incumbent Paul von Hindenburg. [1] Though Hindenburg won the election and retained his office, Hitler made a strong showing and was becoming a political force to be reckoned with in Germany.

Nazi optimism was shaken, however, by two events that took place in the late fall of 1932. Elections held on November 6th of that year resulted in the Nazis receiving over 2 million less votes than elections held just a few months earlier in July. As a result the party lost 34 seats in the Reichstag. Not quite a month later, in early December, 1932, Hitler discovered that one of his top deputies, a man named Gregor Strasser,[2] who had been with him since the early days of the Nazi party, had gone behind his back and entered into secret negotiations with the then new chancellor Kurt von Schleicher [3] to become his vice chancellor. Following this Hitler and the Nazi leadership confronted Strasser at a Berlin hotel on December 5th, 1932, and again a couple days later. The meetings were contentious with the second one ending in a shouting match. The direct result of these meetings was that Strasser submitted his resignation from the party. A short while later he took off on a vacation to Italy, in his wake leaving a somewhat prophetic statement: “Whatever happens, mark what I say. From now on Germany is in the hands of an Austrian, who is a congenital liar (Hitler)… and a clubfoot (Goebbels)[4]. And I tell you the last is the worst of them all. This is Satan in human form.”

At the time of Strasser’s comment Germany was not yet in Hitler’s hands. In fact, with the poor Nazi showing in the elections, followed by Strasser’s departure, Hitler had become depressed and, by some accounts, suicidal. To many it appeared the Nazi movement was coming apart at the seams. Perhaps, through his intrigues, Strasser knew something that even Hitler didn’t know at the time however; that with the help of a former German chancellor and a leading German banker, Hitler’s and the Nazis’ fortunes were about to take a sudden turn for the better.

With the economic turmoil and the influence of the Nazis, as well as the Communists and several other parties in Germany in the early 1930s, the Weimar Republic government was becoming less and less stable. The November, 1932 elections resulted in no clear majority in the Reichstag for any party. Because of the economic scene and the political conflicts, to many Germans the government was regarded as inept and not in control of the country. Keep in mind that Germany had a much longer tradition of being ruled by the Kaisers (Emperors) than it did through the democratic means of the Weimar Republic, which at the end of 1932 was barely 13 years old. To many in the nation at that time a strong hand in government looked mighty desirable. According to the country’s constitution, the office of “Chancellor” (the equivalent of “Prime Minister” in other parliamentary countries) was the chief officer of government. The post was appointed by the president (Hindenburg at the time) and was responsible to both the Reichstag and the president. From about 1930 on, as the Nazi party and the Communist party gained more seats, no party could muster a clear majority in the Reichstag, which rendered it impotent as a governing tool. The result was that the German government was increasingly ruled by presidential emergency decrees, which technically were allowed by a provision in the Weimar constitution.

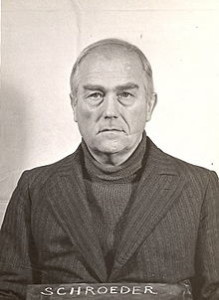

The instability in the German government was reflected by instability in the “chancellor” post itself; which was held among much back biting and scheming by, in succession, Heinrich Brüning [5] (March 1930-May 1932), Franz von Papen (June 1932- November 1932)[6] and the earlier mentioned Kurt von Schleicher (early December,1932-January 28, 1933). Wanting an end to the instability and a strong leader in government (both of which they felt would be good for business), in November of 1932 Hjalmar Schacht and several other leading German businessmen, including Fritz Thyssen, at the time an ardent Nazi supporter and chairman of Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG, one of the largest steel companies in the world[7], wrote a letter to Hindenburg urging him to post Hitler as chancellor. This was followed in early January, 1933 by a secret meeting at the home the German international banker Kurt von Schröder in the town of Cologne. Present at the meeting were Hitler, Nazi SS Chief Heinrich Himmler,[8] Hitler’s secretary and deputy Rudolf Hess,[9] recently resigned chancellor and friend of president Hindenburg, Franz von Papen, and Nazi Party economics advisor Wilhelm Keppler. [10] Papen had been forced out of the chancellor post a month and a half earlier by von Schleicher and was bitter about it. Feeling that von Schleicher, a former friend, had worked to undermine him, Papen would now work to undermine von Schleicher. According to Kurt von Schröder’s sworn statement at the Nuremberg trials after World War II, here is what transpired at this meeting:

“On 4 January 1933 Hitler, von Papen, Hess, Himmler and Keppler arrived at my house in Cologne. Hitler, von Papen and I went into my study where a two-hour discussion took place. Hess, Himmler and Keppler did not take part but were in the adjoining room . . . The negotiations took place exclusively between Hitler and Papen…Papen went on to say that he thought it best to form a government in which the conservative and nationalist elements that had supported him were represented together with the Nazis. He suggested that this new government should, if possible, be led by Hitler and himself together. Then Hitler made a long speech in which he said that, if he were to be elected Chancellor, Papen’s followers could participate in his (Hitler’s) Government as Ministers if they were willing to support his policy which was planning many alterations in the existing state of affairs. He outlined these alterations, including the removal of all Social Democrats, Communists and Jews from leading positions in Germany and the restoration of order in public life. Von Papen and Hitler reached agreement in principle whereby many of the disagreements between them could be removed and cooperation might be possible. It was agreed that further details could be worked out later either in Berlin or some other suitable place…This meeting between Hitler and Papen on 4 January 1933 in my house in Cologne was arranged by me after Papen had asked me for it on about 10 December 1932. Before I took this step I talked to a number of businessmen and informed myself generally on how the business world viewed a collaboration between the two men. The general desire of businessmen was to see a strong man come to power in Germany who would form a government that would stay in power for a long time…”[11]

In addition to this, one of the points stressed by Hitler at the meeting was that Germany needed to become economically autonomous and self-sufficient. To accomplish this it would be necessary that the nation free itself completely of the last vestiges of the hated reparations payments; which, though the future payments had now been written off, still existed in the form of payments now required on the loans and bonds undertaken to make the earlier reparations payments mandated by the Dawes and Young Plans. Along with administering Germany’s now non-existent reparations payments, the BIS also had responsibility for administering these still valid Dawes and Young Plan loan repayments. This situation would soon become a significant problem for the BIS, as is described later in this installment.

After his meeting and agreement with Hitler, von Papen lobbied Hindenburg hard for removing von Schleicher, who had held the office for all of a few weeks, and for posting Hitler to the chancellorship with himself (Papen) as vice-chancellor. He succeeded in convincing Hindenburg, who was already disillusioned with von Schleicher, but who also had a deep distrust of Hitler, that he could control the Nazi leader; and that the alliance of von Papen and his supporters with Hitler and the Nazis would at last bring a majority coalition to the Reichstag and make it functional again. On January 28, 1933, seeing that he was in an impossible position, von Schleicher resigned from office. Two days later, on January 30, 1933 Hindenburg appointed Hitler as chancellor with von Papen as vice-chancellor. From his failed coup in 1923 it had taken the Nazi leader 10 years, but at last he had attained his goal—Adolf Hitler was chancellor of Germany.

As the new chancellor went about the business of consolidating his power any idea that von Papen could control him and the Nazis rapidly went out the window. If anything, the reverse was true. Citing the political gridlock in it, Hitler immediately started urging Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag and to authorize new elections to be held in early March. His plan was to use his now much greater influence to install a Nazi party majority in the legislative body that he could control and which would rubber stamp the actions he planned to take. His plans got an unexpected (or perhaps not so unexpected) boost when on February 27, 1933, the Reichstag building was gutted by an arson-set fire. Historians argue to this day over who really started the fire. A Dutch communist named Marinus van der Lubbe, who had a history of arson, was found inside the burning building, was arrested, charged with the crime and ultimately executed as punishment; but did he really commit the crime? A number of historians feel the Reichstag fire was a classic “false flag”[12] incident, perpetrated by the Nazis to facilitate the dismantling of the Reichstag and to speed the takeover of the German government.

Whatever the truth, Hitler used the Reichstag fire to vast advantage. Again referencing the Weimar constitution provision that gave the president the power to take emergency actions to protect the public safety and order, he pressured Hindenburg into issuing the Reichstag Fire Decree. The Decree was issued on February 28, the day after the fire, and it authorized the suspension of basic rights and detention without trial. With this tool in hand Hitler immediately set about using it to take out his communist opposition and in short order over 4,000 communist party members were arrested. A month later, despite the fact that the elections held on March 5th still did not deliver his hoped for Reichstag majority, Hitler manipulated the legislators into passing “The Enabling Act”, a law which gave the chancellor and his government the authority to adopt laws without approval from the Reichstag for a period of four years. With the Reichstag Fire Decree and the Enabling Act Hitler had legally suspended the Weimar Republic and had, in effect, created a dictatorship in Germany with him and the Nazis at the helm. Over the next few months, using these powers, he moved rapidly to take out any group he thought might provide opposition to the Nazis. The Social Democratic Party was banned and its assets confiscated. In early May, 1933 the leaders of the country’s major trade unions were arrested and the unions themselves dissolved. By June all other political parties were forced to disband and on July 14th, 1933 the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP (the Nazi Party) was declared to be the only legal political party in Germany. With stunning speed, less than 6 months from his appointment as chancellor, Hitler had removed all serious opposition to his rule and had consolidated his power. For all intents and purposes he was now the dictator of Germany.

As these first indications of what Hitler and the Nazis would mean to Germany and the world were playing out, in March of 1933 the German Jewish banker and BIS vice president Carl Melchior, who had played a key role in ending the reparations payments for Germany, was forced by the Nazi government to resign from the BIS because of his religion. Though Melchior had served with the BIS since its inception, his ouster by the Nazis brought nary a peep of protest from his former associates at the cozy “banker’s club” in Basel. Instead the bankers kept to their code, to stay free from politics and to remain neutral as regards the internal affairs of its member nations. Melchior’s fate was regrettable perhaps, but there was nothing to be done about it by the BIS. In fact, and on the contrary, at right around the same time Melchior was being removed, BIS president Gates McGarrah, in a letter to his friend and soon to be appointed BIS president Leon Fraser,[13] spoke highly of Hitler and the Nazis: “Order and discipline in Germany are at the present time exemplary,” McGarrah said in the letter. “The vast majority of the population has the feeling that the fortunes of Germany are in the hands of strong leaders who are inspired by goodwill, so that an optimistic view as regards the future development is justified.”

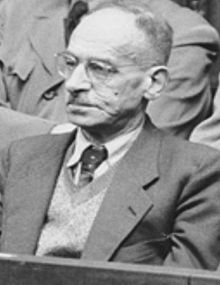

Shortly after this, knowing that he needed him to accomplish the re-armament of Germany, in April of 1933 Hitler asked Hjalmar Schacht to take back his old post of Reichsbank president, which Schacht had resigned from in 1930. Though not a member of the Nazi party himself, and though he did not share the party’s and Hitler’s anti-Jewish bent, Schacht was, nevertheless, a strident and conservative German nationalist who wanted a strong and economically independent country. If the Nazis were the best option for attaining that it was fine with him. He therefore accepted Hitler’s offer and re-assumed the Reichsbank presidency; which also meant that he re-gained his seat on the board of directors of the Bank for International Settlements.

The removal of Carl Melchior as BIS vice president resulted in the elevation of BIS board member and president of the Bank of the Netherlands, Leonardus Trip, to Melchior’s old post, which left an opening on the BIS board. This opening was filled in 1933 when Hjalmar Schacht personally appointed the aforementioned German banker, Kurt von Schröder to the post. Like Schacht, von Schröder was a fascinating character. He was born in Hamburg in 1889 into a well established banking family going back at least 4 generations. Back in 1804 his great grandfather, Johann Heinrich Schröder, relocated to London and joined his older brother’s merchant trading firm there. In 1818, after the retirement of his brother, Johann formed his own merchant trading business, J. H. Schröder & Co. The company prospered and soon opened offices back in the Schröder’s German hometown of Hamburg and later in Liverpool. By the mid 19th century, coincident with the rise of international trading and London as the hub of world finance, the company had branched out into merchant banking and bond issuing. By then Johann had turned the company over to his son John Henry Schröder who successfully ran it for the next 50 years, during which time J. H. Schröder & Co. expanded into one of the largest merchant banks in the British Empire. The company’s status resulted in it performing services for the British royal family for which John Henry was personally honored and acknowledged by Queen Victoria. In 1895 John Henry’s son Bruno Schröder joined the firm as a partner and up to World War I the company enjoyed continued expansion.

The war brought a unique problem, however. Though J. H. Schröder & Co. had been founded in London nearly a century earlier, and for decades had been a leader in the world of British trade and finance, the members of the Schröder family who ran it had always retained their German citizenship. With Germany and England now at war, this made the company liable to seizure by the British government and Bruno Schröder liable to being sequestered by the British for the duration of the war. The problem was solved when, within a few days of the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, Bruno was naturalized as a British citizen. To accomplish this so quickly no doubt took some serious string pulling, but the Schröders had the connections needed to pull them.

Though he and Bruno shared the same illustrious heritage, the young Kurt von Schröder’s side of the family had not moved to England, but was German through and through. He was educated at Bonn University and served in the German military in World War I. Following the war, in 1921 he continued in his family’s banking and financing footsteps and became a partner and director of the J.H. Stein Bank in Cologne, Germany. By the 1930s, according to Adam Lebor in “Tower of Basel”, Kurt von Schröder was at once, “one of the most powerful and influential bankers in Germany,” as well as, “sociable, cosmopolitan, and well-travelled…a reliable international financier, part of the new global elite who were equally at home in the gentleman’s clubs of London or the dining rooms of Wall Street.”

One of Kurt von Schröder’s closest colleagues and friends was a man named Frank Tiarks, who was a partner of Bruno’s in J.H. Schroders and Co.; and who, incidentally, was also on the board of the Bank of England and a close associate of Montagu Norman. Following World War I, with it becoming apparent that New York was replacing London as the world financial epicenter, in 1923 Tiarks set up a Schroders subsidiary in New York, the J. Henry Schröder Banking Corp, also called Schrobanco, which very quickly became successfully involved in the extensive German trading and loans business centered around the Dawes Plan in the mid 1920s. In 1927 Tiarks had Gates McGarrah, who would become the first president of the BIS in 1930, appointed to Schrobanco’s board. At that time Schrobanco was a client of the international law firm Sullivan and Cromwell and was represented by none other than Allen Dulles in many of its negotiations and deals in the mid to late 1920s. So close was Schrobanco with Dulles and Sullivan and Cromwell that by the late 1920s its offices were located in the same building as the law firm—48 Wall Street in New York. Throughout the 1920s, between its operations in Germany, London and New York, though World War I had set things back a bit, the Schröder banking empire managed to survive and expand.

By the early 1930’s both Kurt von Schröder and Hjalmar Schacht were members of a tight group of German businessmen and financiers known as the “Keppler Circle,” which had been formed when Hitler asked businessman and Nazi party member Wilhelm Keppler to recruit a group of men who could be relied upon for economic advice when the Nazis took power. Originally Keppler had recruited about 12 businessmen for the group, but after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor this rapidly grew to 40 or so, representing all aspects of German finance and industry nationally and internationally. Additionally Nazi SS Chief Heinrich Himmler became tightly involved with the group, serving as its protector in exchange for their support. (To facilitate that support, in the mid 1930s von Schröder had established at his J.H. Stein Bank in Cologne an account known as “Special Account S” to be used by the Circle members for depositing pledged funds for use by Hitler and the Nazi government. According to von Schröder, in a letter he wrote to Circle members in early 1936, the funds were to be used for, “…certain tasks outside the budget.” God knows what that meant…and to what use the funds were actually put.)

From all of this one can see that by mid 1933, just after Hitler came to power, the two Germans now on the board of the Bank for International Settlements, Hjalmar Schacht and Kurt von Schröder, were both well connected, not just in Nazi Germany but in the broader world of international banking. They had played key roles in bringing Hitler to power and both had tight communication lines to Montagu Norman and the Bank of England. As noted earlier in this series Norman and Schacht, who were the prime movers behind the formation of the BIS in the first place, were close friends. Through his family’s banking connections and his position on the board of the J.H. Stein Bank in Cologne, Kurt von Schröder was known and did business everywhere. I don’t believe the Nazis and Germany could have been better represented at the BIS than by the two Germans now on its board.

In May of 1933 Gates McGarrah, though retaining a seat on the BIS board, resigned from his post as BIS president. Replacing him was Leon Fraser, an American attorney and economics expert who played a significant role as an advisor in both the Dawes and Young Plan negotiations. With Hitler now in power in Germany, Hjalmar Schacht was getting much pressure from the Nazi leadership to get all of the loans Germany had undertaken earlier under the Dawes and Young Plans to fund its reparations payments written off. The financiers in Wall Street and London who arranged the loans didn’t really care what Germany used the money for; they just wanted to know they’d get their money back. In June of 1933 Schacht told the BIS board members that he supported Germany’s repayment of the Dawes Plan loans but not those undertaken as part of the Young Plan. Germany, Schacht said, simply did not have the funds to pay both. Of course this didn’t sit well with Germany’s creditors and the situation festered until May of 1934 when a conference chaired by BIS president Fraser was held at the Reichsbank in Berlin in an effort to resolve the situation. The conference failed utterly at finding a solution and as a consequence Germany announced a complete moratorium on all of its medium and long term debts, including all Young AND Dawes Plan loans. Needless to say this caused uproar among Germany’s creditors and also in the BIS, which prompted Fraser to issue a statement protesting the “thoroughly arbitrary way in which the German government has disregarded its arrangements.” In the end, however, it seemed there was little the BIS or anyone else could do about it.

Notwithstanding these Nazi strong arm financial tactics, Hjalmar Schacht understood that if Germany were to engage in a blanket default of all of its loan obligations it would do irreparable harm to the country’s credit standing and trust worthiness in the eyes of the world, not to mention further tarnishing the new Nazi government’s already rogue image. His main intent in these actions was to disengage Germany from the BIS administration of these loans, and in this he and the Nazis succeeded mightily. Once this was accomplished he very rapidly negotiated separate agreements with Germany’s creditors in seven different nations, albeit at reduced interest rates and payments. To help free his country from the detested reparations burden, the German Reichsbank president had successfully turned on the bank he helped to create (the BIS).

If there ever were any doubts about the BIS’ ability to fulfill its supposed prime directive—the management of the German reparations payments—Schacht and the Nazis had settled them; at that task it was obvious the BIS was a total failure. As noted earlier, however, the reparations mission was far from the only thing Montagu Norman had in mind when he and Schacht created their “cozy banker’s club.” A clue to this is gotten from an article written by Gates McGarrah, the first BIS president, and published in a magazine called “Nation’s Business”[14] a short while after the BIS was created. In the article he acknowledges that the management of the reparations payments was a routine action that any trust company could have performed, and then goes on to explain what the BIS was really all about:

“The conception seems to have formed in the popular mind that the Bank for International Settlements, which began at Basel, Switzerland, May 20, 1930, was organized merely to handle German reparations payments and the so-called inter-allied debt and that its principal operations are concerned with the German debt payments. That is a mistaken, although an understandable, view. / Although the prime reason for the bank’s creation was to administer the monthly sums paid into it by Germany, this duty has already become the smaller side of the Bank’s activities. The handling of the German reparations payments is a routine operation which any trust company could carry on. Within six months after opening for business the bank has developed much larger and more important activities and has become a medium of service, which is one of the saving features in a tense world situation… / The Bank is completely removed from any governmental or political control. No person may be a director who is also a government official. The Bank is absolutely non-political and is organized on a basis purely commercial and financial, like any properly managed banking institution. Governments have no connection with it nor with its administration.”

As McGarrah states, what the BIS really became (and was intended to be) was an apolitical “medium of service,” and that this was one of its “saving features in a tense world situation.” As Germany and the world in the mid 1930’s rolled on towards World War II, it would soon become apparent to what use this new, non political “medium of service” could be put—thus demonstrating it to be a “saving feature” to no one but the devil.

To be continued…

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2016

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Paul von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military officer, World War I hero and politician who served as the 2nd president of the Weimar Republic from 1925 until his death in 1934. Though an opponent to Adolf Hitler through most of his presidency, in the end he wound up appointing Hitler as chancellor and approving the directives that delivered absolute power into the Nazi leader’s hands.

[2] Gregor Strasser (31 May 1892 – 30 June 1934) was a prominent Nazi Party official who had been involved with the party nearly as long as Hitler himself. Like Hitler, he was imprisoned as a result of his role in the 1923 coup attempt; but, also like Hitler, was released early. An excellent organizer and public relations man, Strasser helped to greatly expand the Nazi Party in the mid to late 1920s, but came into conflict with Hitler by advocating that the party be run in a less dictatorial manner. This ultimately led to Strasser’s disaffection with the Nazis as covered in the article. Gregor Strasser died in June 1934 when he was murdered by members of the Nazi SS at Hitler’s order.

[3] Kurt von Schleicher (7 April 1882 – 30 June 1934) was a German general and politician who was the last man to hold the chancellor office before Hitler ascended to the position. Not a fan of the Weimar Republic, von Schleicher advocated a military oriented dictatorship, ideally with him as the dictator. As described in the article, he lost the chancellorship after much plotting by Hitler and Franz von Papen (whom he replaced on the chancellor post). He then tried to endear himself to Hitler and the Nazis in the hopes of becoming Defense Minister, but Hitler interpreted his efforts as a challenge to the Nazi government. As a result, on exactly the same day as Strasser, June 30, 1934, von Schleicher was murdered by the SS, most likely at Hitler’s order.

[4] Paul Joseph Goebbels (October 1897- May 1, 1945) was one of Hitler’s closest associates and supporters through the 1920s and upon the Nazi assumption of power in 1933 became the Reich Minister of Propaganda, which he held until his death. Goebbels’ Propaganda Ministry quickly gained and exerted controlling supervision over the news media, arts, and information in Germany. He was particularly adept at using the relatively new media of radio and film for propaganda purposes. Topics for party propaganda included anti-Semitism, attacks on the Christian churches, and (after the start of the Second World War) attempting to shape morale. With the war days from ending and Nazi Germany in ruins Hitler committed suicide on April 30, 1945. One day later, on May 1, 1945 Goebbels and his wife committed suicide after killing their six children with cyanide.

[5] Heinrich Brüning (26 November 1885 – 30 March 1970) was a well educated (PhD), German politician and social activist who served as chancellor from March of 1930 to May of 1932, a period coinciding with the onset of the Great Depression. His handling for the Depression was to tighten credit and roll back wage and salary increases; actions which made him very unpopular and cost him his support in the Reichstag. In response to this he and president Hindenburg ran the nation by increasingly utilizing presidential decrees instead of Reichstag passed laws, which, though allowed under the Weimar constitution, set the stage for Hitler to do the same when he came to power. Fearing the Nazis, Brüning fled Germany in 1934, ultimately settling in the U.S. where he had a long career as a professor of government at Harvard. He left the U.S. in the early 1950s for several years to teach in Europe but returned in 1955 and retired to Vermont where he died in 1970.

[6] Franz von Papen (29 October 1879 – 2 May 1969) was a Catholic, German nobleman and politician who served as German chancellor from June to November of 1932. When Hitler was appointed as chancellor in January 1933 von Papen was appointed vice chancellor and served until he resigned in August of 1934. On June 30, 1934 he narrowly missed being murdered along with Gregor Strasser and Kurt von Schleicher among others, because he was being held under house arrest on the orders of Hermann Göring, (at the time one of Hitler’s top deputies) which afforded him a degree of protection. A couple of months earlier von Papen had a made a speech advocating for greater freedoms, which speech angered Hitler and made von Papen a target for assassination. In late June, 1934, fearing a coup from the leadership of the Nazi paramilitary group called the Sturmabteilung (or SA, meaning “Assault Division”, also called the “Brown shirts”) Hitler ordered a purge of the SA leadership. As a result, from June 30 to July 2nd 1934 thousands of people were detained, with many being sent to concentration camps, and at least 85 people were murdered. Though not members of the SA, Hitler took the opportunity to remove permanently both Greggor Strasser and Kurt von Schleicher while, whether by luck or design, von Papen was spared. This June, 1934 purge is now known as the “Night of the Long Knives.” Hitler ultimately found use for von Papen, appointing him as ambassador, first to Austria and later to Turkey. In late April, 1945, von Papen was arrested by elements of the U.S. Glider Infantry and was indicted and tried for war crimes at the Nuremburg trials after the war, where he was acquitted. The German De-Nazification Courts found him guilty, however, and he was sentenced to 8 years of hard labor; but was released on appeal in 1949 and lived the rest of his life a free man. Franz von Papen died in 1969, in the town of Obersasbach, West Germany.

[7] Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG (“United Steelworks” in English) was formed in 1926 when a number of German coal, iron and steel producing companies united into one conglomerate, which made it one of the largest steel companies in the world, at times producing more than any other such company in Europe and even the world. The Chairman of the Board of the company was Fritz Thyssen (9 November, 1873- 8 February, 1951), the son of German industrialist August Thyssen, who had initially established the family in the coal, iron and steel business. Though Fritz Thyssen was initially an ardent supporter of Hitler by 1938 he had become very critical of Nazi economic policies and their persecution of Jews and Catholics (Thyssen was Catholic). After expressing his opposition to Germany going to war against Poland in 1939 his company was nationalized and he fled to France, where he was arrested by the collaborative Vichy French government and returned to Germany where he spent the rest of the war, along with his wife, in a concentration camp. On May 5th, 1945 he was liberated by the U.S. Army and was then tried for being a Nazi supporter, but was acquitted after agreeing to pay 500,000 reichsmarks to those his actions may have damaged. He immigrated to Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1950 and died there in 1951.

[8] Heinrich Himmler (7 October 1900-May 23, 1945) was a leading member of the Nazi party, which he joined in 1923, and was the man Hitler chose to lead the dreaded “Schutzstaffel” (or SS, meaning “Protection Squadron”), which by 1943 he had built into a paramilitary organization nearly a million strong. He also ran the German state police, the Gestapo. It was to Himmler that Hitler gave the task of implementing the “final solution”, and in that capacity he oversaw the construction and operation of the extermination camps that resulted in the deaths of 6 million Jews and untold others. At war’s end in early May, 1945 he attempted to go into hiding but was detained by British forces and then arrested once his identity became known. A few days later, on May 23, 1945, Heinrich Himmler committed suicide.

[9] Rudolf Hess (April 26, 1894-August 17, 1987) was for many years one of Hitler’s most trusted associates, serving as Deputy Führer of the Nazi Party from 1933-1941. Hess joined the Nazi Party in 1920, was with Hitler during his failed coup attempt in 1923, went to jail with him, and while there helped him in the writing of Mein Kampf. Also a good pilot, Hess was the central figure in one of the most bizarre and inexplicable incidents of World War II. On May 10, 1941, he, apparently without Hitler’s knowledge, made a solo flight to England intending to broker a peace between Germany and Great Britain that would leave Hitler free to concentrate his forces and attention on the impending Nazi invasion of Russia. Towards the end of the flight he lost his bearings and, low on fuel, had to bail out over England. He was captured on the ground and incarcerated until the end of the war. Later he was tried at the Nuremburg trials after the war, found guilty of ‘conspiracy to commit crimes’ and ‘crimes against the peace’ and was sentenced to life in prison. While many of his Nazi associates were ultimately released from prison, not so with Hess, who spent the rest of his life in jail. He died in Spandau Prison in Germany in 1987 when he committed suicide by hanging himself.

[10] German businessman (he was chairman of an IG Farben subsidiary as well as owning a photographic gelatin factory) and Nazi Party member Wilhelm Keppler (Dec 14, 1882-June 13, 1960) was one of Hitler’s early financial backers. In 1931 he was appointed by Hitler as the Nazi Party’s economic advisor; and then, after the Nazis took power in 1933, he was appointed as Reich Commissioner for Economic Affairs which he held until 1936. In 1932 Keppler joined the SS and later, during the early years of World War II, was charged with managing the SS confiscated industries in Poland and Russia. At war’s end he was captured, tried and convicted at the Nuremburg trials, and given a prison sentence of 10 years, of which he served two. He lived the remaining years of his life in Germany and died on June 13, 1960 at the age of 77.

[11] It is reported in some references I found that both Allen Dulles and John Foster Dulles, who at the time were partners in the international law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell, were also in attendance at this meeting, and that the meeting itself took place in Berlin. Sullivan and Cromwell and the Dulles brothers represented the American subsidiary of J. H. Schröder & Co (based in New York, the subsidiary was called Schrobanco), the banking company run by Kurt von Schröder’s relatives and which was founded by his great grandfather more than a century earlier in London. You will see in the above statement made at Nuremberg after the war that Kurt von Schröder doesn’t mention either Dulles brother as being in attendance and states that the meeting was in his house in Cologne, so that is what I am reporting here. The reader should keep in mind, however, that Kurt von Schröder had other reasons he may have not wanted to call attention to the Dulles brothers’ role in this meeting. At the time of his statement at Nuremberg he was being charged with war crimes and was in hot water. Allen Dulles had served throughout the war as the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the U.S. World War II precursor to the CIA) station chief in Bern, Switzerland. In late 1945 he was involved in Operation Paperclip, which was the effort to assist getting high placed German Nazis and scientists relocated to the West, which at once denied them to the Soviet Union and made them potential assets to the U.S. in the upcoming Cold War. Kurt von Schröder knew the Dulles brothers well and, no doubt, also knew that in Allen Dulles he had a major potential ally who could assist in freeing him or getting him a light sentence, which in the end is exactly what happened. By 1948 he was out of prison and lived the remaining years of his life as a free man. He died on 4 November, 1966.

[12] A “False Flag” incident is basically a covert intelligence operation in which a government or agency of a government, or even just a few guys in the government or group, stage an incident which makes it appear that nation has been attacked by an enemy when, in fact, it has not. This is done in an effort to arouse patriotic fervor against that “enemy” amongst the people, which then justifies whatever action the government wishes to take against that “enemy.” In the case of the Reichstag fire, it is obvious that Hitler and the Nazis benefitted greatly from it. It gave Hitler the pretext to get Hindenburg to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree which made it “legal” for him to take out the communists and other targeted groups in Germany; therefore, whether it was or wasn’t, the Reichstag fire has all the earmarks of a “False Flag” operation. Several reports I read about the Reichstag Fire while researching this article stated that at one point one of Hitler’s top aides, Hermann Göring, admitted to setting the fire, but that when confronted with this at the Nuremburg Trials he denied it.

[13] Leon Fraser (November 27, 1889-April 8,1945)was a PhD graduate of Columbia University (he later added a law degree to his resume) who worked as a reporter, was admitted to the New York bar, and returned to Columbia to teach public law at his alma mater. When the US entered World War I he enlisted in the army, rose to the rank of major by the end of the war and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his efforts. After the war, in addition to his post with the BIS, he held a variety of administrative positions in both government and private industry, serving as a director, trustee, chairman, and treasurer for a number of businesses and charitable organizations. In 1945, while Fraser was president of First National Bank of New York, apparently despondent over the death of his wife a couple years earlier, he took his own life at his summer home in North Granville, NY. He was 55 years old.

[14] Nation’s Business (originally called “The Nation’s Business”) was a magazine published by the Chamber of Commerce of the United States from 1912 to 1999, primarily for business owners and Chamber of Commerce members nationwide.

Below is the Amazon link to Adam Lebor’s “Tower of Basel”

2 Responses

When maneuvering Hitler to power, to allay everyone’s concerns von Papen assured them he “had Hitler under control”. Yet I find it odd that someone who felt it necessary to control Hitler gave the Nazi’s the Cabinet posts of Interior Minister (the National Police), and Interior Minister of Prussia (State Police over 2/3 of the German population). Criminals are normally put in jail, not given the keys to the prison. Which makes me wonder if von Papen and his gang wanted Hitler to do what he wanted, eliminate the Left and Unions, and carry the fight to the Communists, even the Soviet Union. Germany was after all just as much a bulwark against Communism before WWII as it was after WWII, nor was Hitler the first or last anti-communist fascist western elites supported to fight Communism.

Thanks for your comment, interest and insight, Steven. The point you make about Germany’s anti-communist role both before and after WW II is intriguing, MA