Note: In 1966 Dr. Carroll Quigley,[1] a professor of history at Georgetown University from 1941 to 1976, published a 1300 plus page book covering the history of the world from the late 1800s through the first half of the 20th century. The book is entitled “Tragedy and Hope”, and in it Quigley made several statements that caused conspiracy theorists to sit up and take notice. The most quoted of these statements reads as follows: “…the powers of financial capitalism had another far reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences. The apex of this system was to be the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, a private bank owned and controlled by the world’s central banks, which were themselves private corporations.” Whether Quigley intended his comment to be a statement of conspiracy or not, the fact is that in his statement he made a concise description of a system that has actually come to pass, all the way down to the “secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences.” Today most national central banks in the world are members of the Bank for International Settlements, those banks do own the BIS, and are themselves privately owned, exactly as Quigley stated. Argue about the conspiracy aspect if you want, but it does appear that a “world system of financial control in private hands,” with the BIS at its apex, is exactly what has been created. Whether this is good or bad is for us to judge, but in order to evaluate this scene we must have data. Remarkably, many have never heard of the BIS, and most of those who have know little about it. It is the goal of this series of articles to provide as much of that data as possible. Presented here is Part II of “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements,” which I have entitled, “A Bank of Unprecedented Powers.” As I advised in the earlier installments, to get the most out of this series it should be read in sequence starting with the Introduction and then Part I before you tackle Part II. Both the Introduction and Part I can be found at fromanativeson.com and are linked below. With all that said, please read on. I hope you find this installment interesting and enjoyable…MA

_____________

A Bank of Unprecedented Powers

With the approval of the Young Plan in June of 1929 by the Young Committee negotiators, the next step in the creation of the Bank for International Settlements was to garner the formal approval of the plan by all of the nations concerned with its implementation. For this purpose an international conference was scheduled to take place at The Hague in the Netherlands during the month of August, 1929. Represented at the conference would be the nations of Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, Japan, Poland, Portugal, Rumania and Yugoslavia. Though the Young Committee’s namesake, Owen Young, was an American, the United States would not participate in the Hague Conference. Wanting the reparations issue solved, the US would push for the plan’s approval, however.

Bank of England Governor Montagu Norman wanted no time wasted in getting a proposed constitution drafted for the new bank that could be presented when the Hague Conference convened in August. To that end, in midsummer 1929 he contacted a man named Walter Layton,[2] who was the editor of The Economist [3] magazine, and summoned him to his office to discuss a matter of “extreme importance.” At the meeting Norman told Layton that he wanted him to draw up the constitution of the Bank for International Settlements. Norman explained to Layton that the BIS was being established as part of the Young Plan provisions for resolving the German reparations issue. But, as he described to Layton, Norman had much more in mind for the new bank than a vehicle to facilitate reparations. As detailed by Norman, the BIS would be the world’s first international banking institution. Within its walls central bankers from nations all over the world could meet, away from scrutinizing journalists and politicians. In such a way they could then establish the actions to take and the directives to be implemented to bring much needed order and coordination to the world’s financial systems. As Layton listened, Norman stressed the point to him that the new bank’s constitution must absolutely guarantee the bank’s independence from politicians.

At the time Montagu Norman was the most powerful banker in the world, and not a man one could easily say “no” to. Thus, Walter Layton accepted the task of drafting the new bank’s constitution and set to work. In August the Hague Conference got under way and after some negotiations the Young Plan, including the BIS, was accepted in principle. Seven committees were established to work out the technical details. The seventh of these committees, the Organization Committee, was by far the most important committee as far as the new bank was concerned. This was the committee responsible for writing the statutes governing the bank’s functions and its relationship with whichever country would end up as its host country, thus regulating the new bank’s legal status. The Organization Committee established a broad outline for the BIS, which, according to Adam Lebor in “Tower of Basel,” was described as follows: “The bank would hold central banks’ gold and convertible currency deposits. These deposits could be used to settle international payments without having to either physically move the gold between banks or trade the currency through foreign exchange markets. The BIS would be the international clearinghouse for central banks, the world’s first.” The Organization Committee then undertook to resolve just where the new bank should be located. Norman was lobbying for London, but France objected, instead arguing that it should be located in a small country and thus away from the heavy national influence of the more powerful nations. Ultimately a town was proposed in Switzerland located at the confluence of several international rail lines and conveniently close to the borders of France and Germany. The name of the town was Basel, and it was approved by the Committee in relatively short order. The new bank, therefore, had its host city and country.

While all this was happening Walter Layton was back in London struggling to write the constitution for the BIS. He had run into what was, for him, a significant problem. Norman had been very explicit that the wording of the new bank’s constitution should have the effect of placing it outside the reach of politicians and governments. When queried by the annoyed Norman as to why he was failing at coming up with a constitution that ensured this, Layton replied with an answer that strikes at the very heart of why we should all be concerned about an organization such as the BIS: “Because it’s the right of every democratic government to reserve its freedom of action,” Layton responded. He obviously understood something that Montagu Norman either refused to recognize or discounted severely; which was the simple fact that democratic governments have a sovereign right to vote something out or in. Because of this it would be impossible to guarantee in any version of its constitution that the BIS would exist beyond the reach of the politicians and governments. The words might say so, but that wouldn’t make them true in reality. As an example, in the United States the Federal Reserve Act was passed by Congress in 1913 which authorized the creation of a central bank, the Federal Reserve. Congress today could just as easily undo that creation by repealing the Federal Reserve Act, and the Federal Reserve system would cease to exist. (Something many people feel would be very beneficial) If Congress was to do such a thing it would have a vast effect on the BIS, in which the U.S. today plays a prominent role. Other countries with democratic governments also have this prerogative and could do similar things; and there was/is absolutely nothing the BIS could do about it. Because of this Layton was at an impasse, Norman was frustrated, and the job of structuring the constitution fell to one of the committees created to establish the BIS.

In the end Montagu Norman got everything he wanted written into the statutes that govern the operation of the BIS. Those statutes, agreed to by international treaty at the Hague Conference, remain in force to this day. As reported by Adam Lebor in “Tower of Basel,” they guaranteed the BIS “absolute independence from interfering politicians and governments.” Indeed, Article 10 of the BIS Charter states: “The Bank, its property and assets and all deposits and other funds entrusted to it shall be immune in time of peace and in time of war from any measure such as expropriation, requisition, seizure, confiscation, prohibition or restriction of gold or currency export or import, and any other similar measures.” In addition, according to BIS historian Gianni Toniolo,[4] the bank’s statutes defined its purpose much more broadly than just assisting in resolving the reparations problems. That purpose is stated in the statutes as follows: “To promote the cooperation of central banks and to provide additional facilities for international financial operations; and to act as trustee or agent in regard to international financial settlements entrusted to it under agreements with the parties concerned.” Toniolo also states that the BIS, “although founded by an international treaty sanctioned by national governments, was very much tailored to the views and requirements of the national (central) banks.”

Since the BIS would be located in Switzerland, it would be incorporated under Swiss law. The activities so authorized to it included:

* buying, selling and holding gold for its own account or for central banks

* buying and selling securities other than shares (meaning ownership shares of the BIS itself)

* accepting deposits from central banks

* opening and maintaining deposit accounts with central banks

* acting as an agent of or correspondent for central banks

* entering agreements to act as trustee or agent in connection with international settlements

In addition, with the BIS being created and protected by an international treaty (the Hague Conference), according to Adam Lebor, “The key provisions of the bank’s statutes were given ‘protected status’ and so could only be changed with the consent of all signatories to the Hague Convention.” Though according to the treaty the BIS was an international organization, unlike most international organizations, the most obvious example being the then extant League of Nations, it would not depend on contributions from its members for its finance. Instead, according to Lebor, it would receive its revenue from the fees for the services it rendered on managing the reparations payments and for the “highly profitable” services it would perform for the member central banks.

As the negotiations of the Hague Conference were moving forward an important event occurred that would change the world forever—the stock market crash of 1929. The “bubble” that had been inflating on Wall Street throughout the “Roaring 20’s” finally burst with devastating consequences for many nations; but especially for Germany. Across the 1920s American companies and banks had been investing heavily in Germany, pumping hundreds of millions of dollars into the country. As Hjalmar Schacht had noted, it was only this fact that had allowed Germany to be able to make any reparations payments at all under the Dawes plan. [5] With the crash of ‘29 many of these investors rushed to pull their money out of Germany which had the ultimate effect of crashing the German economy, thus helping to set the stage for the rise of the Nazis, which by 1930 was well under way.

Nevertheless, as the world economies, and specifically that of Germany, were starting to unravel, the nations of the Hague Conference were pushing the Young Plan forward into implementation. As part of this, in February of 1930 the dream of Montagu Norman and Hjalmar Schacht of a “Central Bankers Club” was ushered into reality when the central bank governors of Britain, France, Germany and Belgium, along with representatives from Japan and a group of three American banks, JP Morgan and Co., the First National Bank of New York, and the First National Bank of Chicago, all signed the foundation documents of the Bank for International Settlements. It is interesting to note that the American banks were there in lieu of the American central bank, the Federal Reserve, which was not allowed by the U.S. government to be a member of the BIS. As the U.S. was not represented at the Hague Convention it was not a signer of the treaty. The Federal Reserve would have been welcomed by the other signers as a BIS member nonetheless, but in 1930 there was still a healthy distrust by many Americans of anything European. In particular there were concerns within the U.S. government that the BIS might infringe on U.S. sovereignty—the exact point brought up by Walter Layton when he balked at creating a constitution for the BIS—thus the consortium of American banks above became members instead. The aggregate initial share value for the new bank was established at 500 million Swiss francs and was divided into 200,000 shares at 2500 francs per share. The founding banks would own the shares and their governors would also comprise the BIS board of directors. Each board member could then appoint a deputy director from the same nation who did not himself have to be a central banker, but could come from other financial professions, industry or commerce.

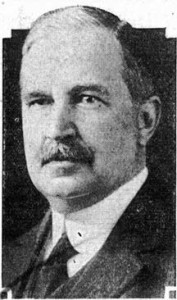

Ironically, considering the U. S. Federal Reserve was not a BIS member, the man chosen as the first president of the new bank was an American with a long history in banking named Gates McGarrah (1863-1940). He had been president of Philadelphia’s Mechanics National Bank for 22 years until it merged with Rockefeller’s Chase National Bank in 1926; at which point he became chairman of Chase’s executive committee. Immediately prior to accepting his post with the BIS in 1930 he was chairman of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for 3 years. In addition, in 1924 he served as the American representative on the 14 person council [6] appointed to oversee the German Reichsbank as part of the Dawes Plan. As a result of all this McGarrah had many contacts, not only in international banking, but also specifically in Germany. Under his leadership the BIS concluded its first year of operation successfully. In his first annual report McGarrah stated that the BIS had assisted during that first year with international financial operations and capital movements and, as an aside, noted that the opportunities for the new bank to engage in constructive service were “almost boundless.” He also reported that, while the bank’s primary objective was not to make money, it nevertheless had made effective investments resulting in over 11 million Swiss francs of profit. In addition the number of shareholding central banks had increased from the original 7 to 23 by the end of the first year, with the national banks of Greece, Romania, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, Czechoslovakia and number of others being accepted. By 1931 the Great Depression may have started laying waste to the world’s economies, especially Germany, but the BIS was up and running profitably.

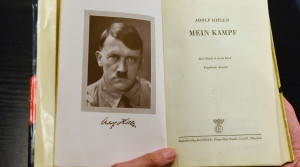

Despite the role he played with Montagu Norman in getting the BIS established, Hjalmar Schacht wrote to J.P. Morgan Jr.[7] in December of 1929 to tell him that he would not be accepting the directorship in the BIS that would be his by virtue of his post as president of the German Reichsbank. Upset that the Young Plan did not dramatically reduce the German reparations, or eliminate them altogether, he resigned from the Reichsbank in March of 1930, turning his post as president over to former German minister of finance and Chancellor, Hans Luther.[8] Six months later he commenced a lecture tour around Europe and the U.S. and at every venue he railed against the reparations and the Young Plan’s endorsement of them, doing his best to create support for the elimination of the hated payments altogether. It was during this tour, while Schacht was crossing the Atlantic from Europe to the States, that he read a book called Mein Kampf [9] by Adolf Hitler; from which he concluded that Hitler displayed a “keen brain.” At the time of Schacht’s tour the National Socialist Party (Nazis) was making significant gains in Germany. The elections of mid September, 1930 had resulted in the Nazis winning 107 seats (a net gain of 95 seats, as they had 12 going into the election) in the Reichstag,[10] a fact which made them the second most dominant party in the nation, next to the Social Democratic Party.

The Nazi surge in Germany was coincident with the economic turmoil resulting from the world wide depression that had commenced with the Wall Street stock market crash of 1929. The crash had precipitated the halting of loans from the U.S. into Germany and many investors and businesses were pulling their money out of the country. In addition many in the U.S. and England looked askance at the Nazi party, regarding it as radical and not to be trusted. The effect of all this on the German economy was massive. Schacht and his replacement at the Reichsbank, Hans Luther, were doing their best to convince their American counterparts and contacts that the Nazi electoral gains would not interrupt or affect the normal flow of finance. After talking with Luther, BIS president Gates McGarrah wrote to his friend, president of the New York Federal Reserve, George Harrison,[11] stating that, “We have the strongest assurances from Dr. Luther that we need not be disturbed about the result of the (German) election…the German people are not revolutionary and in our opinion anything beyond occasional street brawls will be summarily dealt with.” Despite the assurances, panicked investors began to sell their Reichsmarks which prompted a steep decline of the German currency on international markets. This situation gave the BIS its first opportunity to intervene in the financial markets and it did so by authorizing a £300,000 Reichsmark rescue purchase, which, according to McGarrah, had a, “…very helpful psychological effect, including the cessation of offer of marks.” This type of action was not specifically mandated by the BIS statutes or the activities authorized under Swiss law, and illustrates the problem in creating an organization like the BIS that is really answerable to no one but itself. In the early years the new bank was, no doubt, cautious about where and when it could intrude with its “services”; but as time has gone by experience has shown where it could safely intervene and where it should show restraint. As a result, through the years the BIS has bit by bit garnered to itself more and more power, authority and operational territory, as will become apparent to the reader as our story progresses.

In April, 1930, a little over a month after Hjalmar Schacht had stepped down from his post as president of the Reichsbank, his assistant at the central bank, a man named Karl Blessing, [12]wrote a policy statement as to how Germans involved with or working at the BIS should conduct themselves. Blessing had been with the Reichsbank since 1920 and had become Schacht’s personal assistant in 1929. Basically the intent of Blessing and his associates at the Reichsbank, and in the BIS, was to use the new institution that had been created for the express purpose of helping to facilitate the reparations payments, to destroy them. According to Blessing’s policy statement German employees of the BIS should ensure that, “…no important business decisions are made without a German representative having knowledge of them or having had an opportunity to express their opinion.” Grasping the potential importance of the BIS as regards Germany’s national interest, Blessing insisted that the German personnel posted there be the most able that could be found. For all of the new bank’s claims and intensions that it was and would remain free of politics, Blessing understood that when it came to the reparations issue this was impossible. According to Blessing, “The fact that the reparation question has been delegated to a banking institution naturally turns this bank into a political institution, even if this is officially denied.” He, therefore, advocated that the Reichsbank cooperate with the BIS as the “bank for central banks”, but that as regards the BIS’s reparations hat the German goal was to, “gradually create an atmosphere in the Bank in which the anti-reparation bacillus finds fertile ground.” To more directly control this process, in 1931 Blessing left the Reichsbank and took a senior post at the BIS.

1931 was a bad year for Germany, but by year’s end there would be a silver lining of sorts. The elections of that year further exacerbated the social and economic scene in the country, resulting in the National Socialist Party and the German Communist Party taking additional seats in the Reichstag. According to Adam Lebor in “Tower of Basel”, the resulting political instability, “triggered capital flight, which caused a further rise in unemployment and a lack of confidence in both government and the banking system and led to further capital flight, higher unemployment, and more support for the Nazis and the Communists. The Weimar Republic had entered its death spiral.” Five major German banks crashed that year and by June the situation was so desperate that Chancellor Heinrich Bruning stated that he doubted that his country could make its next scheduled reparations payment. Responding to the crisis, U.S. president Herbert Hoover called for the Allied nations to agree to a moratorium on all war debt and reparations payments, which they did for the period of one year. In addition the central banks of England, France, the New York Federal Reserve and the BIS agreed to give Germany an emergency loan of $100 million. Here was another early instance of the BIS engaging in an action not specifically authorized to it, and it didn’t work. The loan may have forestalled the inevitable in Germany for a little while, but by December of 1931 the German minister of finance informed the BIS that his country was in a deepening financial crisis “without parallel.” He asked that the BIS re-examine the whole reparations issue.

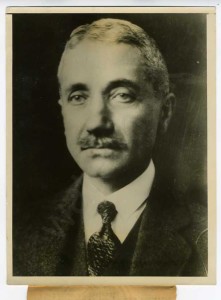

In response to the German request the BIS formed a committee to look into the reparations matter headed by Alberto Beneduce,[13] an Italian BIS board member. The man representing Germany on the committee was Carl Melchior,[14] a German Jewish banker and a veteran of World War I, in which he had been badly injured. Besides being skilled in finance, Melchior was also an excellent negotiator and diplomat; and he represented his country well in the committee. His work, plus the behind the scenes efforts of Karl Blessing and the other Germans in the BIS, paid off big time for Germany when the Beneduce Committee made its recommendations in late December, 1931. The Committee recommended that in order to maintain international peace and economic stability there would need to be an “adjustment” of all intergovernmental reparations and war debts. What this “adjustment” really meant, and what was really intended by the Committee, was that the German reparations payments be cancelled. Six months later representatives of Germany, Great Britain and France met in Lausanne, Switzerland to consider the Beneduce Committee proposal. At the Lausanne Conference the European governments agreed, except for one last payment, to cancel all remaining German reparations payments, pending the Unites States approval of the “adjustment” of the English and French war debts owed to it. Though the U.S. Congress rejected this “adjustment” in December of 1932, which technically meant that the Young Plan German reparations payments should resume, by then the Young Plan reparations agreements were trashed beyond repair. Germany, which at the time was at the brink of the fall of the Weimar Republic and the coming to power of the Nazis and Adolf Hitler, would never again make another reparations payment.

Considering that managing the reparations payments was ostensibly the prime reason for its existence, one would think that with the end of the reparations the BIS would fade from the scene. It didn’t happen because managing reparations was not the main reason the BIS was founded in the first place, despite how it was promoted in the Young Plan. As Adam Lebor reports in “Tower of Basel”: “Under the cover of the Young Plan, as well as the need for an impartial financial institution to administer German reparations payments, Norman, Schacht, and the central bankers had by brilliant sleight of hand created a bank with unprecedented powers and privileges.”

For better or worse the new bank had been created and would persist. To what use its “unprecedented powers and privileges” would be put remained to be seen, however.

To be continued…

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2016

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

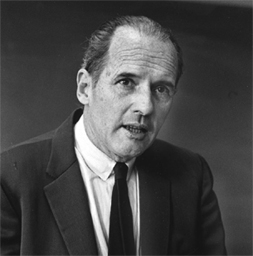

[1] Carroll Quigley (1910-1977) was an American historian and theorist of the evolution of civilizations. He is noted for his teaching work as a professor at Georgetown University, for his academic publications, and for his research on the Round Table movement, which was an association of organizations founded in England in 1909 to foster closer ties between Great Britain and its self-governing colonies. Quigley’s classes at Georgetown were popular with his students and he was a major influence on many of them, including the young Bill Clinton, who acknowledged Quigley in his 1992 address to the Democratic Convention.

[2] Walter Layton (1884-1966) was an economist, newspaper editor and Liberal Party politician in Great Britain for most of the middle part of the 20th century (roughly 1920 to the mid 1960s.) He was appointed editor of The Economist in 1922 and held the post until 1938.

[3] The Economist is an English language weekly newspaper owned by the Economist Group and edited in offices based in London. Continuous publication began under founder James Wilson in September 1843. The Economist refers to itself as a newspaper, but each print edition appears on small glossy paper like a news magazine. In 2006, its average weekly circulation was reported to be 1.5 million, about half of which were sold in the United States. The Economist Group is a British media company headquartered in London. One of the principal owners of the Economist Group is the British branch of the Rothschild family.

[4] Gianni Toniolo (1942-present time) is a Professor of Economics and History who has taught and researched at a number of universities and institutions around the world, including Duke University in the U.S. and the centre for Economic Policy Research in London. His research interests center on European economic growth since 1800, and on the history of money, finance and central banking. In 2005 he published “Central Bank Cooperation at the Bank for International Settlements” under a BIS copyright. The book is essentially a history of the BIS from its founding to 1973.

[5] As an aside, many of these loans and investments were made by banks and companies represented by what was then the most powerful law firm in the United States—the Wall Street firm of Sullivan and Cromwell. Both John Foster Dulles, future U.S. Secretary of State under Eisenhower, and his younger brother Allen Dulles, who would become Director of CIA under Eisenhower and later John Kennedy, were prominent attorneys for the firm; and both developed many profitable business contacts within Germany as a result of their actions during this time. By 1930 Allen Dulles was in charge of the Sullivan and Cromwell office in Paris and was well acquainted with Hjalmar Schacht as well as a number of other key figures in German business. Adam Lebor in “Tower of Basel” states, “While Montague Norman and Hjalmar Schacht had exploited the chaos around the German reparations question to finesse the world’s leading powers into creating the BIS, the Dulles brothers used Europe’s disorder to broker deals and monetary instruments to refinance Germany that were so complex that few outside their offices could understand them.” I won’t be addressing the roles of the Dulles brothers and their law firm extensively in this series of articles as it is not immediately germane to our story, but wanted to ensure it was known that they and their legal firm were prominent in accomplishing the rebuilding of German industry after World War I.

[6] A provision of the Dawes Plan required that a 14 member board composed of 7 Germans and 7 foreigners be appointed to oversee the Reichsbank. The Young Plan dispensed with this.

[7] JP (John Pierpont) Morgan Jr. (1867-1943) was heir to the JP Morgan banking empire which had been built up by his father, JP Morgan. He and his company, JP Morgan and Co., were instrumental in financing the Allies in World War I with loans to France, England and Russia. Following the war his company was a leader in arranging loans for other European nations, including specifically Germany and Italy, both of which ended up as allies against the US, France and Great Britain in World War II.

[8] Hans Luther (1879-1962) was a German politician who held the posts of Minister of Finance (1923), Chancellor (1925-26), president of the Reichsbank (1930-1933) and Ambassador to the United States (1933-1937). In 1923 he worked closely with Hjalmar Schacht, who was Reichsbank president at the time, to halt the German hyper-inflation and stabilize the German currency.

[9] Mein Kampf (meaning “My Struggle”) is an autobiography by the National Socialist leader Adolf Hitler , in which he outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germany. Volume 1 of Mein Kampf was published in 1925 and Volume 2 in 1926. The book was edited by Hitler’s deputy Rudolf Hess.

[10] The Reichstag is basically the German Parliament. It is also the name of the building in which the Parliament meets.

[11] George Harrison (1887-1958) was an American attorney, insurance executive and banker. He was educated at Yale and was a member of the Skull and Bones secret society. After serving as general counsel to the Federal Reserve Board, Harrison served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York for 13 years starting in 1928. He left in 1941 to become president of New York Life Insurance Company. During World War II, he was Secretary of War Henry Stimson’s special assistant for matters relating to the development of the atomic bomb. He served with Stimson on the eight-member Interim Committee which examined problems expected to result from the bomb’s creation and which recommended direct military use of the bomb against Japan without specific warning. Harrison chaired the committee when Stimson was absent. Harrison returned to his position at New York Life after the war, becoming chairman of the company’s board in 1948.He died in 1958 and is buried in Washington DC.

[12] Karl Blessing (1900-1971) had a long career as a German banker both before and after World War II. In 1937 he became a member of the Executive Board of the Reichsbank but was dismissed along with a number of others for criticizing Nazi policies. He was active in the resistance against Hitler and was to have been named Minister of Economics had the assassination plot and coup of July, 1944 against Hitler succeeded. The Gestapo never discovered that Blessing was to become Economics Minister and so, unlike many of the others involved, he escaped arrest and survived the war to continue his banking career.

[13] Alberto Beneduce (1877-1944) was an Italian Socialist politician, financier and scholar. He helped to found and headed two significant state run banks in Italy through the 1920s and 30s and it was in that capacity he became associated with the BIS. Though a Socialist, he collaborated with the Mussolini Fascist regime running the country at the time, serving as Mussolini’s economics advisor through the 1930s. He retired in 1940 due to health problems and died in 1944.

[14] Carl Melchior (1871-1933) was a Jewish German attorney and banker. As noted in the article he served in the German military in World War I during which he was injured. Upon recovery he went to work for the German government, serving as an advisor to for the financial negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference that resulted in the Treaty of Versailles. Through the 1920s he played an increasingly prominent role in Dawes and Young Plan negotiations, gaining international recognition for his command of the legal and financial issues involved. With the creation of the BIS in 1930 he served as a board member until 1933 when, with the Nazis coming to power in Germany, he was forced to resign due to being Jewish. He died in December, 1933 of a stroke.

2 Responses

> Carroll Quigley* “Bill Clinton, who acknowledged Quigley in his first inaugural address.”

This common statement appears to be more fictional accounts presented as “history,” see here: http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=46366

Hi Marc, Thanks for your interest and your comment. You are correct that Clinton’s acknowledgement of Quigley did not take place in his first inaugural address and I have edited the piece to reflect this. It was actually during Clinton’s address to the Democratic Convention of 1992 that he spoke glowingly of his old proffesser Quigley. I appreciate you calling this error to my attention. MA