Note: Presented here is Part I of a series of articles entitled “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements.” I have entitled this first installment “The Founding”. To get the most out of the series they should be read in sequence, starting with the Introduction which is linked here:

I used a number of references in researching this material but by far the most useful and those I relied the most upon were “Tragedy and Hope” by Carroll Quigley, “Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler” by Antony Sutton and “Tower of Basel” by Adam Lebor. All three are recommended reading on this subject, though I must say that Quigley’s book, at well over 1,000 pages, is a bit daunting. It is well indexed, however, and I had little problem finding the relevant passages I needed. I have included links to these books at Amazon at the bottom of this article, should the reader want to procure his or her own copies. The whole purpose of this series is to enlighten the reader on just what the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was originally, how it came to be, who created it and what it is now. To understand what is happening in today’s world of global finance and how that world affects each one of us, it is vital to understand the role played by the Bank for International Settlements. That understanding starts with the history of the BIS, and that is the subject of Part I. With that preamble understood, here is “Hitler’s Bank: The Unknown Story of the Bank for International Settlements—Part I—The Founding.” I hope you find it enlightening…MA

_______________________

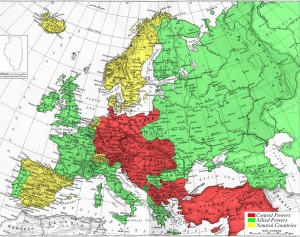

To that point in their history, in terms of devastation, loss of life and sheer destruction, the countries of Europe had never experienced anything like World War I. The war, which was ignited in June of 1914 when a Yugoslav nationalist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, lasted just over 4 years. It pitted against each other two major alliances of nations: the Central Powers, which included Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman empire; and the Allies, composed of Great Britain, France, Russia and, a little later, Italy. Fueled by 20th century advanced military technology that had outstripped the 19th century military tactics in use at the time, World War I resulted in the deaths of over 9 million military personnel between both sides. In addition to this, roughly 7 million civilians died in the carnage, often due to ethnic genocides. The world had never before witnessed killing on such an industrial scale, as took place in World War I.

The United States, when it finally joined the fray in 1917, came in on the side of the Allies. For most of the war the U.S. had adopted a neutral position and stayed free of the conflict; with president Woodrow Wilson promoting the slogan “he kept us out of war” to narrowly win re-election in 1916. But by January of 1917, with the German adoption of a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare on any ships trading with the British or French, Wilson began to change his tune. Some 128 Americans had already died when the British passenger liner Lusitania was sunk by a German U-boat in 1915. With this new German policy it was predictable that more Americans would die. On top of this Germany, convinced that the United States would soon enter the war against it, was promoting to Mexico that it become a German ally against the U.S. and that Germany would help Mexico recover Texas, Arizona and New Mexico; territories that had been lost by it to the U.S. in the prior century. When 7 merchant ships with Americans on board were sunk by the Germans Wilson made his decision, and called on the anti-war factions supporting him to take the opportunity to end all wars by winning this one; stating that the war was so important that the United States had to have a voice in the peace conference ending it. Ultimately Congress fell in line and declared war on Germany on 6 April, 1917, and so U.S. forces fought in the war in Europe over the last year of the conflict.

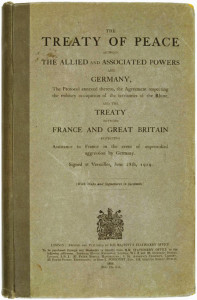

Following battlefield reversals, across a 6 week period from late September to early November, 1918 the nations of the Central Powers one by one surrendered to the Allies. The last to give in, on November 11th, was Germany. Eight months later, on June 28, 1919, after 6 months of negotiations in Paris, the Treaty of Versailles was signed which formally ended the war between the Allies and Germany. (The other nations of the Central Powers each signed separate treaties between themselves and the Allies.) [1]

The provisions of the Versailles Treaty were particularly harsh for Germany and, despite president Wilson’s efforts to establish the League of Nations to prevent future wars, ultimately set the stage for World War II. A specific provision of the Treaty, later to become known as the “War Guilt Clause”, required that Germany accept responsibility for starting the war and therefore for the damage that had been inflicted on the Allies, chiefly France and Belgium; but also to a lesser extent the other European Allied nations. (The other nations of the Central powers had similar provisions in their treaties as well.) The Treaty, therefore, required that Germany and her allies make reparations to the nations so damaged and mandated that a Reparation Commission be established in 1921 that would assess the resources available to those nations and establish the amount of the final reparations figure to be paid. In the meantime Germany was required to pay the equivalent of 20 billion goldmarks in various commodities and securities to cover the costs of the Allied occupation, food and raw materials. (Germany’s pre-war, gold-backed monetary unit was the “goldmark”. The country went off the gold standard in 1914 and from then until 1923 the currency unit was the “papiermark”, or “paper mark” in Englsh. Both monetary units were often just referred to as “marks”.) Of this amount, by 1921 she had managed to pay about 9 billion marks (about U.S. $2.2 billion.)

Ultimately the Reparation Commission set up a time table of payments called the London Schedule of Payments. On 5 May, 1921 the London Schedule of Payments set the total amount of reparation payments owed at 132 billion marks, or roughly US $33 billion, even though it was understood by the Allies that this figure was beyond the ability of the Central Powers to pay. Germany’s allies were in desperate situations economically in the wake of the war and Germany itself could not pay that amount. Yet France in particular, and to some degree Belgium, wanted to stick it to the Germans. France’s goal in the Treaty of Versailles negotiations was to ensure that Germany could never again threaten her. As a result, other provisions of the treaty required that Germany’s army be limited to 100,000 men, she was not allowed an air force and she was allowed only 6 naval vessels and no submarines. Germany was required to surrender all of her overseas colonies to League of Nations supervision and had to surrender various territories it had acquired to a number of nations, including Belgium, France, Denmark, Poland and Czechoslovakia. Other territories were taken and put under League of Nations supervision. In addition an Allied occupation force was to be stationed on the west bank of the Rhine River for 15 years.

Some of the Allied experts disagreed with the severity of penalties being levied against Germany. What was the point of demanding reparations that could never be paid? The result was that it was finally agreed that while the announced figure would remain at 132 billion marks, in reality Germany and her allies would only have to pay 50 billion marks. (US $12.5 billion) This was done as a ruse to give the impression to the French and English people that harsh penalties were being exacted against Germany for her aggression, while in reality the remaining 82 billion marks were never expected to be paid. As Germany had paid 9 billion already, she was then required to issue bonds at 5% interest for the remaining 41 billion marks. The payment schedule required payments of 2 billion marks per year, plus a percentage of the value of German exports, to retire the bonds; and could be paid in commodities such as coal, timber, livestock etc., or in funds. At that rate Germany would be paying reparations for years to come.

Needless to say, the provisions of the Versailles Treaty went down sideways with the German government and people, who felt humiliated by them. The “War Guilt Clause” of the treaty was particularly detested and the prevailing belief amongst many Germans was that in signing the treaty the nation had signed away its honor. A decade later Hitler and the Nazis would use this dissatisfaction to their full advantage in assuming power in Germany and in leading the country and the world, once again, to war.

The German inability, as well as unwillingness, to make these payments was compounded in the early 1920s by a hyper-inflation that resulted from the German government’s excessive borrowing (and resultant money printing) from the Reichsbank—the German central bank. Between 1921 and 1923 the German mark declined in value against the British pound from a par value of about 20 per pound to the unbelievable figure of 20 billion marks per British pound in December, 1923. Those were the days you may have heard about, when people would take a wheelbarrow full of cash to the store to buy a loaf of bread. The inflation shattered the confidence in the mark as a monetary unit, basically destroying it as a currency. By July of 1922 it had gotten bad enough that Germany demanded of the Reparations Commission a 30 month moratorium on all cash reparation payments. The British were willing to go along with this to some degree, but France, Belgium and Italy, feeling that Germany had made no real effort to confront its responsibility to make the payments, would only do so if they were allowed to take possession of productive German resources such as forests, mines and factories as a means to generate income to make the payments. As a result, on January 9, 1923 the Reparations Commission by a vote of 3-1 declared Germany in default on her payments. Two days later an international crisis was precipitated when French, Belgian and Italian troops began to occupy the Ruhr, a resource laden 1800 square mile area in northwestern Germany. (please see map for location)

The Ruhr, though a relatively small area, contained 10 percent of Germany’s population but produced 80 percent of the nation’s coal, iron and steel. 70 percent of the country’s freight traffic originated there and its railway system, operated by 170,000 people, was the most complex in the world. In response to this invasion Germany ceased all reparations payments at once, declared a general strike of all workers and in general adopted a policy of passive resistance to the occupying forces. The German government created more inflation by printing more money to support the striking workers. Meanwhile the occupying forces tried to run the complex Ruhr production and transportation systems with less than 10 percent of the work force required, roughly 12,500 troops plus a very few cooperating Germans. It was a situation ripe for violence and within a few months, due to German reprisals and Allied response, 400 people were killed and 2100 wounded. This was the situation that led to the first of two major efforts at coming up with solutions to the problem of German reparations payments and which, in case you were wondering, ultimately led to the creation of the Bank for International Settlements. (No, I haven’t forgotten what this series is about.)

The first effort at solving the German reparation dilemma was called “The Dawes Plan” and it marked the overt intrusion of international bankers into attempts to solve the problem. The Dawes Plan was conceived by an international committee of financial experts headed by American banker Charles Dawes (Founder and president of the Central Illinois Trust Co.) The committee met in Paris from mid January, 1924 to early April, 1924, when they issued their recommendations. According to Georgetown Professor of International Relations Carroll Quigley [2]in his book Tragedy and Hope, “The Dawes Plan was largely a J. P. Morgan [3] operation.” Earlier during the war Dawes had supported the efforts of the Morgan banks in arranging a $500 million loan to France and England to finance the war. (Basically Morgan needed the support of a non-Morgan banker to get the loan approved, as president Wilson generally felt that loans of this sort violated the U.S. position of neutrality in the war. With Dawes’ help the loan went through.) Also on the Dawes Plan committee of experts was another man with strong Morgan connections, Owen Young, who was president of both General Electric and RCA at the time.

The main points implemented by the Dawes Plan were as follows:

- The Ruhr area was to be evacuated by foreign troops and returned to Germany.

- Reparation payments would begin at one billion marks the first year, increasing annually to two and a half billion marks after five years.

- The Reichsbank would be re-organized under Allied supervision.

- The sources for the reparation money would include German transportation, excise and customs taxes.

- Germany would be loaned $800 million, mostly from the United States.[4]

The issue of bonds authorized by the Dawes Plan took place in New York and London simultaneously in October of 1924 and was quickly oversubscribed.[5] Seeing this other banks jumped on board, eager to fund companies doing business in Germany and also to loan money to Germany. Between the years of 1924 and 1928, according to Adam Lebor in his book “The Tower of Basel”, Germany borrowed $600 million a year, half of it from American banks.

Since the overall German reparations payments were not reduced by the Dawes Plan, but only re-structured by it, Germany was not ecstatic about accepting it; but in the end had little choice. At least it got the Allies out of the Ruhr and defused the international crisis; and for this Charles Dawes was named a co-recipient of the 1925 Nobel Peace Prize. His enhanced reputation also, no doubt, contributed to his being named Calvin Coolidge’s running mate and thus becoming Vice President of the United States in 1925.

As for the United States, since it was not interested in reparations payments and was not receiving them, its prime concern in resolving the issue was that the other Allied nations receiving the reparations payments could then use them to repay their war debts owed to the U.S. The Dawes plan facilitated this by creating a circular flow starting with loans into Germany (see point 5 above), which in turn facilitated reparations payments to the European Allies who then, in turn, flowed them back to the U.S. to pay off their war debts.

Everybody’s happy—or so it was hoped. But, as usual in such situations, it’s not that simple.

As an aside, I don’t know how many of you have ever wondered how a nation such as Germany, vanquished at the end of World War I and in economic turmoil over the next 6 years (until 1925), could rebuild itself to the point that within a mere 14 years (World War II in Europe began in 1939) it would once again engulf the world in war. How does that happen? In point 5 of the Dawes Plan above you have a big part of the answer. According to Carroll Quigley in “Tragedy and Hope”: “Using these American loans, Germany’s industry was largely equipped with the most advanced technical facilities…(Germany was) able to rebuild her industrial system to make it the second best in the world by a wide margin.” Quigley then goes on to say: “It is worthy of note that this system was set up by international bankers and that the subsequent lending of other people’s money to Germany was very profitable…the international bankers sat in heaven, under a rain of fees and commissions.” Another researcher, Antony Sutton, in his book “Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler”, comments as follows: “These loans are important for our story because the proceeds, raised for the greater part in the United States from dollar investors, were utilized in the mid-1920s to create and consolidate the gigantic chemical and steel combinations of I.G. Farben [6] and Vereinigte Stahlwerke [7]…These cartels not only helped Hitler to power in 1933; they also produced the bulk of key German war materials used in World War II.”

Another significant event occurred in Germany in late 1923. In response to the devastating inflation in the country the German government appointed to the post of currency commissioner a 46 year old banker and economist named Hjalmar Horace Greely Schacht, and gave him near dictatorial powers over the German economy. A fascinating character, Schacht would play a vast role in both the formation of the Bank for International Settlements and the rise of Hitler and Nazi Germany. Though born in 1877 in a former section of the German empire that is now part of Denmark, Schacht’s parents had spent years in the United States and intended to name their son Horace Greely Schacht in honor of the famed American, anti-slavery journalist and politician.[8] Schacht’s grandmother would have none of it, however, and insisted on a proper Danish first name; and thus the boy was christened “Hjalmer.”

In order to help stabilize the German economy, since the “mark” was devastated as a medium of exchange, a new currency called the “rentenmark” had been introduced into Germany. Most currencies of the day were gold-backed, but with the lack of gold in Germany following World War I the rentenmark’s value was pegged to the value of all of German land and holdings used for agriculture, industry and business. The word “rente” in German means “mortgage”. In effect a vast mortgage was taken out on this land based on the mark’s pre-war value, which came to 3.2 billion marks, which then allowed the issue of 3.2 billion rentenmarks. Of course this would present a problem if someone wanted to redeem their rentenmarks, since they couldn’t really walk away with a chunk of real estate; but this was not a problem to Schacht. In his excellent book, The Tower of Basel, author Adam Lebor illuminates why: “As long as Schacht was in office, nobody would want to redeem a rentenmark,” Lebor states.“He brilliantly understood the key point of psychology of money, which is as valid today as it was in the hyper-inflation of the 1920s: the appearance of financial stability creates monetary value. If people believed that someone was in charge, that the chaos would end, and that the rentenmark had value, then it would be valued.”

The printing of the German rentenmark notes commenced on November 15th, 1923. The German people could then exchange their useless marks for rentenmarks at the seemingly unreal rate of one trillion marks for one rentenmark. The rate of conversion to dollars was 4.2 rentenmarks to a dollar, which was the pre World War I mark to dollar exchange rate. The aim, Schacht said, was to “make German money scarce and valuable.” In this he succeeded mightily; so well in fact that a month later, on December 22nd, 1923, Schacht was promoted and became, in addition to currency commissioner, the president of the national central bank of Germany—the Reichsbank.

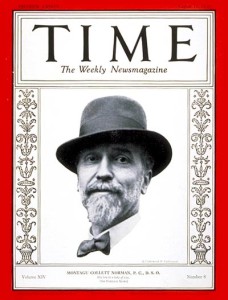

With the rentenmark functioning as a currency Schacht had brought the German inflation under control. His next step was to begin the process of building a gold reserve to give the currency a more sound backing. To this end, on December 31st 1923 he travelled to London and was met at the Liverpool Street train station by none other than the legendary governor (the equivalent of president) of the Bank of England himself—Montagu Norman. At the end of 1923 Norman had been governor for over 3 years and was widely considered one of the most powerful and influential men in the world. A simple utterance from him, made public, was enough to move markets up or down. For all of his influence and power, however, Norman was an intensely shy man; introverted to the point of neurosis. He hated publicity, which was ironic, since the press tracked his every move. He didn’t like being recognized or socializing and was subject to fainting. Despite these reserved qualities, should a junior fail to meet his standards he could become extremely angry, occasionally yelling and throwing things.

Schacht’s purpose in visiting Norman was to convince him to authorize a loan for $25 million from the Bank of England to a new Reichsbank subsidiary he had established called the Gold Discount Bank. With the loan and the implied approval of the Bank of England and Norman, Schacht knew that the new bank would immediately alter world perception of Germany’s financial prospects, thus opening financial doors in both Wall Street and London. The two bankers instantly took to each other and Schacht got his loan. Their meeting in London on the last day of 1923 started a friendship between the two that lasted until Norman’s death in 1950, (Schacht died in 1970) and would have consequences that reverberate to this day, as we shall see.

With the assistance of these loans Germany was rebuilding and, with the Dawes Plan restructuring, had resumed reparations payments. However, the German government, people, and particularly Hjalmer Schacht, still hated them and wanted them gone. The fact was that Germany was only able to make its payments because it was borrowing from other nations. By 1928 Schacht felt that it was no longer feasible to keep doing this and that Germany needed to be fully productive again so as to become self sufficient. Even if Germany was to keep making reparations payments, he saw this as the only way to go about it. Meanwhile France, Belgium and the other Allies were adamant the reparations continue. The upshot was that a new conference to resolve the reparations issue was convened in Paris in February of 1929, this time chaired by RCA and General Electric president (as well as J.P. Morgan ally) Owen Young.

The conference got under way cordially but quickly became contentious, as Schacht and the Germans were proposing a complete re-structuring of the reparations schedule requiring relatively small payments payments of $250 million per year for the next 37 years; whereas the French, headed by Bank of France governor Emil Moreau, were demanding $600 million a year for the next 62 years. Neither man would yield from their position and the resultant impasse persisted. Despite the discord, one idea put forth by Schacht and Montagu Norman was getting some traction: the creation of a new bank for the prime purpose of managing Germany’s reparations payments. The two bankers held that the new bank would keep the issue free of politics and would manage the payments on a purely financial basis—something that was actually very unlikely, considering how politically charged the reparations issue was. In actual fact Norman had been considering similar ideas for years. In 1925 he sent a message to Federal Reserve of New York governor Benjamin Strong in which he stated: “I rather hope that next summer we may be able to inaugurate a private and eclectic [9] Central Banks ‘Club’, small at first, large in the future.” I have no direct evidence of it now, but I highly suspect that Schacht and Norman, considering their friendship and that they were both heavily promoting the new bank during the Young committee haggling, had discussed just such a thing, probably a number of times between 1925 and 1929. Using the stated purpose of managing the German reparations payments, in this new bank they saw a vehicle to actually do it.

To make the long and relatively complex story of the Young conference negotiations relatively short, on June 7, 1929 all sides finally reached agreement and what was to be called “The Young Plan” was drafted and adopted. The Young Plan called for German reparations payments of $29 billion over 58 years ($500 million per year) and Germany would be restored to full control of her own economic policy, free from the oversight mandated by the Dawes Plan[10]. In addition, the new bank promoted by Norman and Schacht to administer the payments was accepted and authorized. Writing later about the bank’s creation, Schacht stated: “…my idea of a Bank for International Settlements had met with such enthusiastic response from all those those taking part in the Young Conference that soon there was not one among them who would not have claimed the suggestion as his own.”

One gets the feeling that Schacht’s claiming of the new bank idea as his own was just fine with the shy and retiring Montagu Norman, however. Though he preferred to remain in the background, his idea of a “Club for Central Banks” was about to become a reality.

To be continued…

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2016

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] At the same time the treaty negotiations were taking place in Versailles the government of Germany was undergoing a sea change. Immediately following the German capitulation to the Allies in November of 1918 a social revolution took place in the country that more or less ousted the old aristocratic class along with the Kaiser (“Kaiser” is German for “Emperor”) and imperial form of government and replaced it with a new constitution. The result was a democratic republic that became known as the “Weimar Republic”, due to the fact that the new constitution was drafted in the German city of Weimar; an important cultural center for not just Germany, but all of Europe. I comment on this here to provide context for what was happening in Germany at the time so the reader understands the major upheaval and political change that was taking place in the country while the Versailles conference was happening. The Weimar Republic was officially established on 11 August, 1919 and lasted until 1933 when Hitler and the NAZIs assumed power.

[2] Carroll Quigley (1910-1977) was an American professor of history at the Foreign Service School of Georgetown University. Prior to that he taught at Harvard and Princeton. Among his many students was a young Bill Clinton, who would go on to become president of the United States. Quigley is most famous for his definitive work on the world’s history and power structure, “Tragedy and Hope,” which is one of the major research references I used for this piece. It is in “Tragedy and Hope” that Quigley made his famous claim: “The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole. This system was to be controlled in a feudalist fashion by the central banks of the world acting in concert, by secret agreements arrived at in frequent private meetings and conferences.” In light of this “aim” the importance of establishing the “Bank for International Settlements” can clearly be seen.

[3] John Pierpont “J.P.” Morgan (April 1837 – March 1913) was an American financier and banker who dominated corporate finance and industrial consolidation during his time. In 1892, Morgan arranged the merger of Edison General Electric and Thomson-Houston Electric to form General Electric (GE). He was instrumental in the creation of the United States Steel Corporation, as well as in the creation of the U.S. Federal Reserve. At the height of Morgan’s career during the early 1900s, he and his partners had financial investments in many large corporations and had significant influence over the nation’s high finance and Unites States Congress members. Upon his death in 1913 he left his business and fortune to his son John Pierpont Morgan Jr.

[4] There seems to be some confusion on the actual amount of the loan authorized by the Dawes Plan. Carroll Quigley and Antony Sutton in their books state the figure was $800 million while other sources state it was 800 million marks. For the purposes of this article I am using dollars.

[5] In the world of investing there are two broad categories of investment….those being “equities” and “bonds”. “Equities” are shares of ownership, such as stocks. “Bonds” are fundamentally loans at interest. Cities, governments and corporations all use bonds as a means to raise money (borrow) for projects that is be repaid from taxes or revenue received across varying periods of time. The bonds are made available to investors to invest in. “Oversubscribed” simply means there are more investors willing to invest than the bond issue requires or authorizes.

[6] According to Antony Sutton in his book “Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler”: “The Farben cartel dated from 1925 when organizing genius Herman Schmitz (with Wall Street financial assistance) created the super-giant chemical enterprise out of six already giant German chemical companies—Badische Anilin, Bayer, Agfa, Hoechst, Weiler-ter-Meer, and Griesheim-Elektron. These companies were merged to become Internationale Gesellschaft Farbenindustrie A.G (literally meaning ‘community, or company of interests’) .—or I.G. Farben for short.” Schmitz, who was Farben’s general manager from 1925 to 1935 and CEO from 1935-1945, was tried and convicted for war crimes at the Nuremburg trials after the war, serving a 4 year prison sentence. I.G. Farben had American holdings and companies as well that in 1929 were merged to form American I.G. Chemical Corporation, later called General Aniline and Film, a wholly owned subsidiary of German I.G. Farben. The board of American IG included prominent Americans from finance and industry. Sutton thoroughly explores this connection in “Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler” and I highly suggest reading it.

[7] “Vereinigte Stahlwerke” means “United Steelworks”, and, like I.G. Farben, was created from the merging of several companies in 1926. By the 1930s it was one of the largest German companies, producing 40% of German steel and 20% of German coal.

[8] Horace Greely (1811-1872) was the editor of the New York Tribune for many years and also a Congressman for a short time. He actually ran for president against Ulysses Grant in 1872 but died before the first electoral vote was cast. He is most famous for popularizing the phrase “Go west young man…”

[9] “Eclectic” means “deriving ideas, style, or taste from a broad and diverse range of sources.”

[10] A provision of the Dawes Plan required that a 14 member board composed of 7 Germans and 7 foreigners be appointed to oversee the Reichsbank. The Young plan dispensed with this.

Book Links Follow

http://www.amazon.com/Tragedy-Hope-History-World-Time/dp/094500110X/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1462156187&sr=1-1&keywords=tragedy+and+hope+by+car

One Response

Good post. I learn something totally new and challenging on websites I stumbleupon every day.

It’s always helpful to read articles from other authors

and use something from other websites. https://Www.waste-ndc.pro/community/profile/tressa79906983/