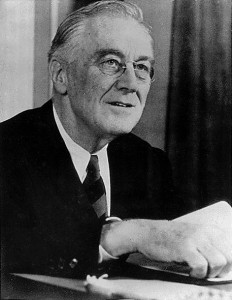

Preface: In earlier blogs in the “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series [1]I have made reference to the anti-colonial views of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as expressed in World War II’s Atlantic Charter [2] and in the wartime conferences at Tehran (1943) and Yalta (1945)[3]. When it comes to Vietnam this is significant because that country was a French colony prior to World War II. In May of 1940 Hitler’s Nazi Germany invaded France and within a month or so the French surrendered. Understandably the collapse of France had a weakening effect on the French colonial government in Vietnam, which in June of 1940 resulted in the French acceding to Japanese demands that it be allowed to control Vietnam’s northern border with China. (Japan had inaugurated World War II in the Pacific when it invaded China in 1937, thus its interest in controlling China’s southern border.) In September of 1940 the Japanese invaded Vietnam outright and took control of the country; but lacking the administrative resources to run it they kept the French administration in place as a collaborative government, much along the lines of what the Germans did in France with the Vichy French government.[4]

Preface: In earlier blogs in the “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series [1]I have made reference to the anti-colonial views of U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as expressed in World War II’s Atlantic Charter [2] and in the wartime conferences at Tehran (1943) and Yalta (1945)[3]. When it comes to Vietnam this is significant because that country was a French colony prior to World War II. In May of 1940 Hitler’s Nazi Germany invaded France and within a month or so the French surrendered. Understandably the collapse of France had a weakening effect on the French colonial government in Vietnam, which in June of 1940 resulted in the French acceding to Japanese demands that it be allowed to control Vietnam’s northern border with China. (Japan had inaugurated World War II in the Pacific when it invaded China in 1937, thus its interest in controlling China’s southern border.) In September of 1940 the Japanese invaded Vietnam outright and took control of the country; but lacking the administrative resources to run it they kept the French administration in place as a collaborative government, much along the lines of what the Germans did in France with the Vichy French government.[4]

Resisting the Japanese in Vietnam were Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh fighters. As a result of Roosevelt’s anti-colonial statements Ho Chi Minh, the Viet Minh and all Vietnamese Nationalists took hope that they would be allowed to form their own government when the Japanese were at last defeated. The mechanism Roosevelt envisioned to accomplish this in colonial territories was to set those areas up under trusteeships to be run under the auspices of the soon to be created United Nations (April-June 1945) until such time as the people of the area could choose and set up their own government. On April 12th, 1945 President Roosevelt died. While the United Nations Charter, established in San Francisco between April and June of 1945, did pay lip service to the principal of self determination for all nations; and while it did set up a trusteeship council, when push came to shove it was determined at the Potsdam Conference [5] in July/August of 1945 that the Europeans (Great Britain, France and the Netherlands), would be allowed to take their colonies back.

The Japanese finally surrendered on September 2nd, 1945. On that same date Hoh Chi Minh and his Viet Minh supporters, using the U.S. Declaration of Independence as a model, published their own Vietnamese Declaration of Independence and established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. I am sure that, based on Roosevelt’s statements throughout the war, they expected the help of the United States in fending off the expected French efforts at re-establishing their Vietnam colony. Despite many appeals by Hoh Chi Minh to the U.S. government, that help never came. The question is why? This is a key question. Had the United States handled this situation differently, and lived up to its anti-colonial pronouncements, the Vietnam War would never have happened. It is easy to say that Roosevelt died and that his anti-colonial sentiments were not shared by his successor Harry Truman with equal fervor; but Truman made his own comments in support of the right of a people to self determination.

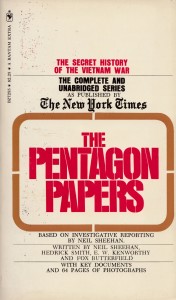

In an effort to shed light on this question I am publishing verbatim this section from the Pentagon Papers [6]which deals with this time period and subject. Take from it what you will. In reading the Pentagon Papers I have found that some of it is at odds with other data I have discovered and that also, at times, it leaves out key data which results in a distorted impression of what actually happened. Nevertheless I believe there is value to what is stated here as it provides more insight into the overall situation. I have footnoted the article when necessary to provide information as to who or what someone or something is, and added the definitions of some words. With all that understood, here is “Indochina in U.S. Wartime Policy, 1941-1945” from the Pentagon Papers….MA

____________________

INDOCHINA IN U.S. WARTIME POLICY, 1941-1945

“Significant misunderstanding has developed concerning U.S. policy towards Indochina in the decade of World War II and its aftermath. A number of historians have held that anti-colonialism governed U.S. policy and actions up until 1950, when containment of communism supervened. For example, Bernard Fall [7] (e.g. in his 1967 postmortem book, Last Reflections on a War) categorized American policy toward Indochina in six periods: “(1) Anti-Vichy,[8] 1940-1945; (2) Pro-Viet Minh, 1945-1946; (3) Non-involvement, 1946-June 1950; (4) Pro-French, 1950-July 1954; (5) Non-military involvement, 1954-November 1961; (6) Direct and full involvement, 1961- .” Commenting that the first four periods are those “least known even to the specialist,” Fall developed the thesis that President Roosevelt was determined “to eliminate the French from Indochina at all costs,” and had pressured the Allies to establish an international trusteeship to administer Indochina until the nations there were ready to assume full independence. This obdurate (stubborn or hard headed) anti-colonialism, in Fall’s view, led to cold refusal of American aid for French resistance fighters (against Japan), and to a policy of promoting Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh as the alternative to restoring the French bonds. But, the argument goes, Roosevelt died, and principle faded; by late 1946, anti-colonialism mutated into neutrality. According to Fall: “Whether this was due to a deliberate policy in Washington or, conversely, to an absence of policy, is not quite clear. . . . The United States, preoccupied in Europe, ceased to be a diplomatic factor in Indochina until the outbreak of the Korean War.” In 1950, anti-communism asserted itself, and in a remarkable about face, the United States threw its economic and military resources behind France in its war against the Viet Minh. Other commentators, conversely—prominent among them, the historians of the Viet Minh—have described U.S. policy as consistently condoning and assisting the re-imposition of French colonial power in Indochina, with a concomitant (simultaneous) disregard for the nationalist aspirations of the Vietnamese.

Neither interpretation squares with the record; the United States was less concerned over Indochina, and less purposeful than either assumes. Ambivalence characterized U.S. policy during World War II, and was the root of much subsequent misunderstanding. On the one hand, the U.S. repeatedly reassured the French that its colonial possessions would be returned to it after the war. On the other band, the U.S. broadly committed itself in the Atlantic Charter to support national self-determination, and President Roosevelt personally and vehemently advocated independence for Indochina. F.D.R. regarded Indochina as a flagrant example of onerous colonialism which should be turned over to a trusteeship rather than returned to France. The President discussed this proposal with the Allies at the Cairo, Teheran, and Yalta Conferences and received the endorsement of Chiang Kai-shek[9] and Stalin; Prime Minister Churchill demurred. At one point, Fall reports, the President offered General (Charles) de Gaulle[10] Filipino advisers to help France establish a “more progressive policy in Indochina”–which offer the General received in “Pensive Silence.”

Ultimately, U.S. Policy was governed neither by the principles of the Atlantic Charter, nor by the President’s anti-colonialism but by the dictates of military strategy and by British intransigence on the colonial issue. The United States, concentrating its forces against Japan, accepted British military primacy in Southeast Asia, and divided Indochina at 16th parallel between the British and the Chinese for the purposes of occupation. . U.S. commanders serving with the British and Chinese, while instructed to avoid ostensible alignment with the French, were permitted to conduct operations in Indochina which did not detract from the campaign against Japan. Consistent with F.D.R.’s guidance, U.S. did provide modest aid to French–and Viet Minh–resistance forces in Vietnam after March, 1945, but refused to provide shipping to move Free French troops there. Pressed by both the British and the French for clarification U.S. intentions regarding the political status of Indochina, F.D.R- maintained that “it is a matter for postwar.”

The President’s trusteeship concept foundered as early as March 1943, when the U.S. discovered that the British, concerned over possible prejudice to Commonwealth policy, proved to be unwilling to join in any declaration on trusteeships, and indeed any statement endorsing national independence which went beyond the Atlantic Charter’s vague “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.” So sensitive were the British on this point that the Dumbarton Oaks Conference of 1944 [11], at which the blueprint for the postwar international system was negotiated, skirted the colonial issue, and avoided trusteeships altogether. At each key decisional point at which the President could have influenced the course of events toward trusteeship–in relations with the U.K., in casting the United Nations Charter, in instructions to allied commanders–he declined to do so; hence, despite his lip service to trusteeship and anti-colonialism, F.D.R. in fact assigned to Indochina a status correlative to Burma, Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia: free territory to be re-conquered and returned to its former owners. Non-intervention by the U.S. on behalf of the Vietnamese was tantamount to acceptance of the French return. On April 3, 1945, with President Roosevelt’s approval, Secretary of State Stettinius[12] issued a statement that, as a result of the Yalta talks, the U.S. would look to trusteeship as a postwar arrangement only for “territories taken from the enemy,” and for “territories as might voluntarily be placed under trusteeship.” By context, and by the Secretary of State’s subsequent interpretation, Indochina fell into the latter category. Trusteeship status for Indochina became, then, a matter for French determination.

Shortly following President Truman’s entry into office, the U.S. assured France that it had never questioned, “even by implication, French sovereignty over Indo-China.” The U.S. policy was to press France for progressive measures in Indochina, but to expect France to decide when its peoples would be ready for independence; “such decisions would preclude the establishment of a trusteeship in Indochina except with the consent of the French Government.” These guidelines, established by June, 1945–before the end of the war—remained fundamental to U.S. policy.

With British cooperation, French military forces were reestablished in South Vietnam in September, 1945. The U.S. expressed dismay at the outbreak of guerrilla warfare which followed, and pointed out that while it had no intention of opposing the reestablishment of French control, “it is not the policy of this government to assist the French to reestablish their control over Indochina by force, and the willingness of the U.S. to see French control reestablished assumes that [the] French claim to have the support of the population in Indochina is borne out by future events.” Through the fall and winter of 1945-1946, the U.S. received a series of requests from Ho Chi Minh for intervention in Vietnam; these were, on the record, unanswered. However, the U.S. steadfastly refused to assist the French military effort, e.g., forbidding American flag vessels to carry troops or war materiel to Vietnam. On March 6, 1946, the French and Ho signed an Accord in which Ho acceded to French reentry into North Vietnam in return for recognition of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam as a “Free State,” part of the French Union. As of April 1946, allied occupation of Indochina was officially terminated, and the U.S. acknowledged to France that all of Indochina had reverted to French control. Thereafter, the problems of U.S. policy toward Vietnam were dealt with in the context of the U.S. relationship with France.”

________________

Summary: This document from the Pentagon Papers is clear in the fact that President Roosevelt “vehemently advocated independence for Indochina,” and that he felt that Indochina was a “flagrant example of onerous colonialism which should be turned over to a trusteeship rather than returned to France.” (It is possible Roosevelt was upset with the French due to their rapid collapse to and collaboration with the Japanese in Indochina) Roosevelt had closed both Joseph Stalin and Chiang Kai-shek on the idea of trusteeships for colonial territories leaving only Churchill and the British as protesting the idea among the major World War II allies. Roosevelt died on April 12th, 1945, several weeks before the San Francisco Conference convened to create the United Nations. The above document states that on September 2nd Roosevelt authorized Secretary of State Stettenius to issue a statement to the effect that the U.S. would look to trusteeship as a postwar arrangement only for “territories taken from the enemy,” and for “territories as might voluntarily be placed under trusteeship,“ which was interpreted as meaning there would be no trusteeship for Indochina. Despite this, as noted in Part III of this “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series, later in May of 1945 the US Ambassador to China Patrick Hurley sent a letter to Harry Truman, Roosevelt’s replacement as President, stating that before his death Roosevelt told him that the trusteeships for Indochina would be organized at the UN San Francisco meeting when it took place. The text of the letter follows: “In my last conference with President Roosevelt…I told him that the French, British and Dutch were cooperating to prevent the establishment of a United Nations trusteeship for Indochina…the President said that in the coming San Francisco Conference there would be set up a United Nations Trusteeship that would make effective the right of colonial people to chose the form of Government under which they will live as soon as in the opinion of the United Nations they are qualified for independence.” Regardless, apparently Truman never got the anti-colonial memo and the trusteeships for Indochina never came to pass. The result was that the French were handed the Indochina colonies back, which led directly to the First Indochina War between France and Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh army, to be followed by the United States and its 20 year disaster in Vietnam. How different things would have been had Roosevelt’s anti-colonial wishes become reality. Personally, I consider that failure one of the great mistakes of U.S. foreign policy in the post World War II era. MA

Copyright © 2014

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] For more information on Roosevelt and anti-colonialism please see “Ramping Up The Vietnam War” Parts I and II, both of which can be found in this blog site (fromanativeson.com).

[2] The Atlantic Charter was a policy statement created by the United States and Great Britain in August of 1941 which laid out their goals for the post World War II world. Among those goals were restoration of self government to those deprived of it and no territorial changes made against a people’s wishes. The Atlantic Charter was specifically cited by Hoh Chi Minh in his appeals to the US for assistance in preventing the French from re-establishing Vietnam as their colony.

[3] The Tehran (28 Nov-1 Dec 1943) and Yalta (4-11th Feb 1945) conferences were meetings of the leaders of the US, Great Britain and Russia (Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin) during World War II. As confirmed in the Pentagon Papers, at both conferences the subject of self determination was discussed with both Stalin and Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek agreeing with Roosevelt and Winston Churchill disagreeing.

[4] When Nazi Germany occupied France in 1940 they left the southern part of the nation unoccupied and under the control of a collaborative French government seated in the town of Vichy in central France. This collaborative government, known as the “Vichy government”, still had control of French colonies, one of which was Vietnam. When the Japanese invaded Vietnam they established their own version of the “Vichy government” using the existing French administration.

[5] The Potsdam Conference (17 July 1945-2 August 1945) took place at the town of Potsdam in Germany and was the last of the meetings of the wartime leaders of the US, Great Britain and Russia. The main agenda concerned the handling for war torn Europe, but it was at this conference that it was agreed that France could re-assume colonial control of Southeast Asia.

[6] In 1967 US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had a study conducted of the entire history of the United States involvement in Vietnam. The study resulted in a 7,000 page top secret report entitled “United States-Vietnam Relations: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense”. The report chronicled the secret history of the US war in Vietnam and included information on US actions withheld from the media and lied about to Congress. In 1969 the report fell into the hands of former Defense Department analyst and Rand Corporation researcher Daniel Ellsberg. Ellsberg had contributed to the report so knew of its existence. At first he tried to get Senators who were opposed to the Vietnam War to read the report on the Senate floor, but this did not happen. Ultimately he gave the report New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan who started publishing it in the New York Times on Sunday, 13 June, 1971. The Nixon administration attempted to block the publication of the report with a court order and for 15 days the Times was prevented from publishing. Then on June 30th, 1971 in an historic ruling the Supreme Court found that the release of the report did not constitute a threat to national security and the Times was allowed to continue publishing. By then Ellsberg had released the report to a number of other papers as well. The now public report ever since has been known as “The Pentagon Papers”.

[7] Bernard Fall was a native Austrian who moved to the US in the early 1950s. As a child his family moved to France and as a 16 year old he fought the NAZIs with the French resistance and later the French Army. After the war he attended University in Paris and Munich. Upon coming to the US Fall completed his graduate studies at Johns Hopkins and Syracuse Universities after which he embarked on an academic career as a professor, first at American University and later at Howard University where he taught international relations. Fall made a study of the situation in Indochina while at Johns Hopkins and in 1953 travelled to Vietnam to witness the First Indochina War for himself. Based on what he observed he predicted the French failure in Vietnam, which came to pass at the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954. Later, as the US Vietnam involvement increased, he made 6 more trips to the Southeast Asian country. Traveling with US and Vietnamese troops into battle situations he observed the American Vietnam War up close and personal. While he supported the idea of American involvement in Vietnam to stop communism he disagreed vehemently with the oppressive South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem as well as US tactics in the war. Based on these views he predicted that the US would also fail in Vietnam, which of course also came to pass in 1975. Fall wrote a number of articles and 7 books on Vietnam and Southeast Asia, including “Last Reflections on a War”, the book referred to in the Pentagon Papers. In 1967, while accompanying US Marines on a mission, Bernard Fall died in Vietnam when his jeep hit a land mine. He was 41 years old at the time of his death.

[8] For information on the Vichy French government please see footnote number 4 in this article.

[9] Chiang Kai-shek was the leader of the Republic of China during World War II. Following that war he and his Chinese Nationalists fought a Civil War for control of the country with the Chinese Communists led by Mao Zedong (known in the West as Mao Tse-tung). In 1949 the Communists defeated the Nationalists and Chiang Kai-shek fled to the island of Taiwan where, with US support, he ruled for another 25 years. He died in 1975 at the age of 87.

[10] Charles de Gaulle (1890-1970) was a French military leader during World War I and II and a French statesman after. He was decorated for his service in World War I and was wounded several times as well as becoming a prisoner of war. When France was invaded by Germany in 1940 de Gaulle was a colonel in the French Army. He was quickly promoted to Brigadier General because of his successes against the Germans, but despite his efforts France fell rapidly to the NAZIs. When the French government capitulated to the NAZI’s in June, 1940 he refused to accept it and operating out of London set up the Free French movement and organized French resistance in the colonies and in France. After the war he served as the leader of the French Provisional Government and destroyed the remnants of the Vichy French government that had collaborated with the NAZIs. In that capacity he was also responsible for sending the French Far East Expeditionary Corp to reclaim French colonies in Indochina. De Gaulle retired in 1946 but un-retired in 1958 to become President of France, a post he held for 11 years, until 1969. He died a year later in 1970 and is today recognized as a French national hero.

[11] The Dumbarton Oaks Conference took place in August, 1944 at the Dumbarton Oaks estate in Washington DC. The conference participants included the US, Great Britain, Russia and the Republic of China. (The Russian representative would not meet with the Chinese representative so the Conference took place in two separate meetings to accommodate everyone.)The purpose of the Conference was to look at and evaluate preliminary proposals for an organization of nations that would maintain peace and security in the world. The outgrowth of this in 8 months was the San Francisco Conference at which the United Nations was created.

[12] Edward Stettinius Jr. was US Secretary of State under both Presidents Roosevelt and Truman in the years 1944-45. Stettinius was the chairman of the US delegation to the San Francisco conference at which the United Nations was established, and played a major role in its formation. He died young at the age of 49 in 1949.