Note: In April of 1954, during the waning days of the First Indochina War, when it became obvious that the French were in serious trouble as a result of the Viet Minh’s [1] siege of the French army at Dien Bien Phu, the United States came very close to intervening in the war on behalf of France. It is an episode of US involvement in Vietnam that most Americans know nothing about, so I thought I would take a little side excursion from the “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series to tell you about it. Here is the story of “The Day We Didn’t Go To War”…please read on…MA

In the September 14, 1954 edition of “The Reporter”[2] magazine there is a very interesting article written by veteran political and foreign affairs journalist Chalmers Roberts.[3] The article is entitled “The Day We Didn’t Go To War” and it provides an inside look at just how close the United States came to intervening militarily to salvage the French army during the crucial Viet Minh siege at the battle of Dien Bien Phu—the battle that ultimately cost France its Vietnam colony.

According to Roberts, on Saturday, the 3rd of April, 1954, while President Eisenhower was off at Camp David working on a speech he was to deliver that coming Monday, eight key Congressional leaders were called to a secret meeting with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. [4]The Senators attending the meeting were Senate Majority Leader William Knowland (Republican) of California, Eugene Millikin (Republican) from Colorado, Democratic Senate Minority Leader from Texas, Lyndon Johnson and Democrats Richard Russell (Georgia) and Earle C. Clements (Kentucky). Also attending were Republican Speaker of the House Joseph Martin (Massachusetts) and Democratic Representatives John W. McCormack (Massachusetts) and J. Percy Priest (Tennessee). When the Congressmen arrived they were surprised to find that it was not just Dulles they were meeting with. Also in the State Department conference room with the Secretary of State were the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Arthur W. Radford, [5]Under Secretary of Defense Roger Kyes, Navy Secretary Robert Anderson and Dulles’ assistant for Congressional relations, Thurston B. Morton. It was obvious to the Congressmen this meeting was about more than just a Secretary of State briefing.

Dulles opened the meeting and got right to the point. What was wanted by President Eisenhower, Dulles said, was a joint resolution from Congress to authorize the use of US air and naval power to relieve the Viet Minh’s siege of the French army at Dien Bien Phu. Dulles stated that the President felt that it was extremely important that Congressional leaders feel as the President did about Vietnam; which was essentially that the small Southeast Asian country could not be allowed to fall to the Communists, lest the rest of Indochina should be lost as well. After Dulles had laid the premise of the meeting Admiral Radford took over and got down to specifics. He brought out a map of Indochina and used it to get across the importance of Vietnam strategically. He followed that up by stating that the French forces had already been under siege at the Dien Bien Phu fortress for three weeks, and that due to poor communications into the battle zone the Americans weren’t even sure of the French were still holding out. The situation therefore, according to the Admiral, was urgent.

Somewhat taken aback, the legislators queried the Admiral as to what the plan would be, should Congress approve the resolution. The Admiral responded that 200 planes from US aircraft carriers then stationed in the South China Sea, plus Air Force planes land-based in the Philippines, would be used in a single strike against Viet Minh positions at Dien Bien Phu.

The legislators asked if that would mean we would be at war.

Admiral Radford replied that, yes, we would be in the war.

The Congressmen asked what would happen if the strike did not succeed in relieving the siege—would the U.S. then follow up with more military action?

The Admiral replied that, yes, there would be follow up action.

The Congressmen then wanted to know if that follow up action would involve the use of land forces, to which the Admiral could not give a definitive answer.

Senator Clements then asked the Admiral if the plan had the approval of the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“No!” the Admiral replied.

“How many of the three agree with you?” Clements asked.

“None!” replied the Admiral

“How do you account for that?” asked Clements.

Admiral Radford responded by stating that he had spent more time in the Far East than any of the others and that he understood the situation there better.

Lyndon Johnson then chimed in with the consideration that with the United States having had to put up 90% of the men and money for the Korean War, shouldn’t we know before any resolution was passed who it was that would provide the men and funds for this proposed Vietnam venture? Had Dulles discussed this plan with the United Nations or any of the allies?

Dulles stated that he had not, that time was too short for that.

The Congressmen were concerned that US intervention in Vietnam could lead to general war with the Soviet Union and Communist China, and also that it could spur further Chinese military action in Korea. Dulles answered this by stating that the Soviets did not want a general war now and that he thought the Soviets were capable of restraining the Chinese.

Even so, in the end the Congressmen were unwilling to consider the resolution without Dulles first lining up some allies for the effort. Several of the legislators, according to Chalmers Roberts’ article, felt that had they agreed with Dulles about the resolution the Chiefs and the administration would not even have waited for the rest of Congress to act, but that US planes would have been winging towards Dien Bien Phu with no further notice to Congress or the American people.

Fortunately that did not happen and the U.S. did not go to war following that 3 April meeting. What did happen was an intensive 3 week period in which Dulles and the Eisenhower administration went about trying to gather up allies in support of saving the French in Vietnam. It was during this 3 week period that the famous “Domino Theory”, the idea that if one country in Southeast Asia fell to Communism it would lead to the rest of them falling, like a row of dominos once one domino is knocked over, was first broadly spoken of with President Eisenhower using the concept in a speech. Both Admiral Radford and Vice President Richard Nixon, in speeches around the same time, endorsed the concept with Nixon even stating that if the French could not avert disaster at Dien Bien Phu the U.S. would need to send in troops.

By the end of the first week after the meeting with the Congressional leaders Dulles had spoken with the representatives in Washington DC of Great Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and the three French backed governments in French Indochina—Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia. What Dulles was seeking was for these nations to all sign on to a joint declaration of intent to be issued at the time of the U.S. military intervention to explain to the world what was being done and why; and to also warn the Communist Chinese against coming in to the war as they had done in Korea. He likely would have succeeded with this except for the fact that the British completely refused to go along with the idea. On April 10th Dulles took off for London to meet with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill [6]and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden to handle them on going along with the intervention. Instead, as a result of the meeting Dulles had to give up on the idea of immediate intervention, but did apparently, or so he thought, succeed in getting some rudimentary agreement on the idea of a “NATO” type alliance for Southeast Asia that would be known as SEATO (Southeast Asian Treaty Organization).

Dulles thought that the SEATO agreement could be rapidly created and would provide the united front that he sought with allies that Congress required in order to pass the joint resolution for intervention. He returned to Washington and called for a SEATO drafting meeting of the treaty on April 20th only to have the British refuse to allow their ambassador to attend. Apparently there was some dispute about what Dulles thought the British agreed to regarding SEATO, and what the British thought they had agreed to. For the time being SEATO would have to wait.

A couple days later Dulles flew off to Paris for a NATO[7] meeting with British Foreign Minister Eden and the French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault. On Friday, April 23rd, Bidault showed Dulles a telegram from the French commander in Vietnam that stated that unless there was a massive air attack to help the French the Dien Bien Phu fortress would soon fall. Dulles told Bidault that the U.S. could not intervene at that time. The next day, Saturday the 24th, the U.S. Joint Chiefs Chairman Admiral Radford arrived in Paris and he and Dulles met with Eden and told him that the French were requesting assistance to prevent a disaster at Dien Bien Phu. Admiral Radford explained to Eden the plan to use air strikes from South China Sea carriers and from the Philippines that he had described 3 weeks earlier to the Congressional leaders. Dulles told Eden that if the allies agreed to the plan President Eisenhower was prepared to ask Congress on Monday, April 26th for the joint resolution approving the intervention and that the airstrike at Dien Bien Phu would follow on Wednesday the 28th.

Eden told Dulles and Admiral Radford that what they were proposing was very serious, amounting as it did, to war. He insisted on hearing the request for intervention from the French Foreign Minister Bidault himself. Bidault confirmed the request to Eden, who then still withheld his approval, stating he was not authorized to decide the issue by himself, but that it was a matter for the British cabinet to decide. Eden also was very clear to Dulles and Radford that he believed the scheme was a terrible idea and that he personally opposed it. He stated that he thought that within 48 hours of the proposed airstrike ground troops would be called for, just like what happened in Korea several years earlier.

With the failure to get the British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden to agree to the airstrike on the 24th of April, Dulles gave up on trying to push through the U.S. Dien Bien Phu intervention. He composed a letter to the French Foreign Minister telling him that the U.S. could not intervene to help France because that to do so exceeded President Eisenhower’s Constitutional authority; and also because any U.S. action could only take place as part of a ‘united’ action, approved by allies—an agreement that did not at that time exist. He also told him in the letter that U.S. military commanders felt it was too late to save Dien Bien Phu.

Thus the United States did not go to war in Vietnam in April of 1954; and Dien Bien Phu fell to Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh army two weeks after Dulles’ meeting in Paris with the British and French Foreign Ministers. At the end of his article Chalmers Roberts reveals that later, in May of 1954, he asked many Senators and Representatives what they would have done if President Eisenhower had just skipped the Secretary of State meeting with the Congressional leaders on April 3rd and flat out asked Congress for the joint resolution approving military intervention in Vietnam on behalf of the French. Roberts says that, “their replies made clear that Congress would, in the end, have done what Eisenhower asked, provided he had asked for it forcefully and explained the facts and their relation to the national interest of the United States.” For whatever reason, Eisenhower never did make that request directly to the Congress.

A final footnote on this brief but intense period of the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam comes from General Matthew Ridgway,[8] who in 1954, along with Admiral Radford, was serving in the Joint Chiefs of Staff as the Chief of Staff of the US Army. General Ridgway was one of the three members of the Joint Chiefs mentioned earlier in this article who did not support Admiral Radford in his efforts at getting the United States to intervene for the French in Vietnam. In his memoirs General Ridgway shared his sentiments about the matter:

“When the day comes for me to face my Maker and account for my actions,” General Ridgway wrote, “the thing I would be most humbly proud of was the fact that I fought against, and perhaps contributed to preventing, the carrying out of some harebrained tactical schemes that would have cost the lives of thousands of men…” General Ridgway then emphasized his point by adding, “To that list of tragic accidents that fortunately never happened I would add the Indo-China intervention.”

Copyright © 2014

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Viet Minh is an abbreviation for “Việt Nam Độc Lập Đồng Minh Hội” literally meaning “league for the independence of Vietnam”. The Viet Minh were a political and military coalition originally formed to free Vietnam from the French but who also fought the Japanese in World War II when they invaded Indochina in 1941. With the defeat of the Japanese the Viet Minh resumed the fight against the French when they tried to re-assert control of Indochina after World War II.

[2] The Reporter was an American news magazine published bi-weekly in New York from 1949 to 1968.

[3] Chalmers Roberts (1910-2005) was a long time journalist and correspondent for the Washington Post as well as the author of five books in addition to the magazine articles he wrote. For decades he reported on the Cold War, the nuclear arms race and the Washington political scene.

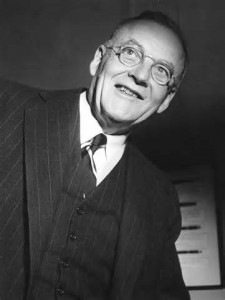

[4]John Foster Dulles (1888-1959) US Secretary of State under President Eisenhower from 1953-59, Dulles was rabidly anti-communist and was instrumental in the US support of the French during the First Indochina War (1946-54) and later in the creation of South Vietnam as a non-Communist US protectorate. He was the brother of Allen Dulles who was Director of the CIA from 1952 to 1961.

[5] Admiral Arthur Radford (1896-1973) was a career naval officer who served as the Commander of the Pacific Fleet in the late 1940’s and who was appointed by President Eisenhower to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff post in 1953. Radford was a strong advocate of naval air power and an ardent anti-communist who recommended that the United States should threaten the Red Chinese with the nuclear bomb to get them to back down in Korea. He strongly advocated US intervention with naval air power on behalf of the French in Indochina.

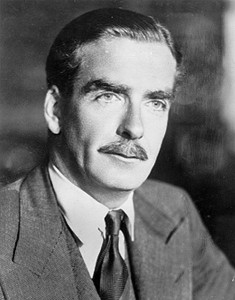

[6] After serving as the Prime Minister of Great Britain during the bulk of World War II Winston Churchill (1874-1965) was voted out of office in 1945. In 1951 he was re-elected and served as Prime Minister until 1955. Churchill is considered one of the greatest war time leaders of the 20th century.

[7] NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) was formed in 1949 as a response to the threat posed by the Soviet Union with its expansionist policies in Eastern Europe. It pledges its member nations to a policy of mutual defense in the event of an attack by an outside party. NATO is headquartered in Brussels, Belgium

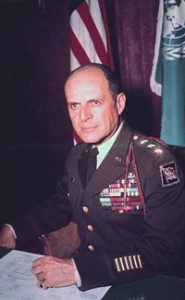

[8] General of the Army Matthew Ridgway (1895-1993) was a career Army officer who served in World War II and Korea and was named to replace General Dwight Eisenhower in 1952 as the Supreme Allied Commander for Europe for the then new North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Ridgway was named Chief of Staff of the US Army in 1953 and served in that capacity until 1955 when he retired. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1986 by President Ronald Reagan.

2 Responses

Good stuff again, Arnoldian! Christ, one can easily imagine the result if this scheme had gone through. It would have been the Vietnam War we came to know, only a decade earlier.

Pendleton

Pendleton!

Yes, when I encountered this particular little window onto that slice of time I wondered to myself if it would have ended up better or worse for the US if we would have gotten into Vietnam militarily in ’54 as opposed to when we did in 64/65. Either way ain’t good but I wonder how it would have been different. I also have encountered some unverified reports from the French Foreign Minister at the time (’54) that Dulles offered nukes to the French to help them handle their situation. I don’t know if there has ever been a more suppressive duo operating at the same time in our government than the Dulles brothers.

More to come soon.

Arnoldian