Note: In the first two parts of this series on the Vietnam War we have covered the events in Vietnam from the end of World War II to the beginning of what today is known as “The First Indochina War”; the conflict between France and the indigenous Viet Minh army of Ho Chi Minh who resisted French efforts to re-impose colonial control over Vietnam following the war. The First Indochina War would ravage the small nation of Vietnam for most of the next eight years—from November of 1946 to the spring of 1954. After the end of World War II the world changed rapidly. The United States and the Soviet Union, who were allies during World War II, became enemies locked in “The Cold War”; a supposed clash of the political and economic ideals of the Capitalist Democracy of the United States vs. the Communist ideals of the Soviet Union. The Cold War in reality was only “cold” in the sense that the US and the Soviet Union never engaged in outright conflict. It would dominate US foreign policy for the next four decades and resulted in a number of localized “hot” wars and conflicts that brought about millions of deaths worldwide and nearly 100,000 combat deaths of US military personnel. The most devastating of these localized Cold War conflicts for the US was the Vietnam War. As already covered in this series, Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh had also been US allies in the World War II fight against the Japanese. As the First Indochina War took hold in Vietnam, so did the anti-Communist ideology of the Cold War take hold of US attitudes towards the Viet Minh and Ho Chi Minh, who was himself a Communist. This has everything to do with why the United States became so tragically involved in Vietnam and is the subject of “Ramping Up the Vietnam War Part III-The First Indochina War.” Please read on…MA

In late May of 1945 the US Ambassador to China, Patrick J. Hurley, sent a letter to President Truman that stated the following:

“In my last conference with President Roosevelt…I told him that the French, British and Dutch were cooperating to prevent the establishment of a United Nations trusteeship for Indochina…the President said that in the coming San Francisco Conference there would be set up a United Nations Trusteeship that would make effective the right of colonial people to chose the form of Government under which they will live as soon as in the opinion of the United Nations they are qualified for independence.”

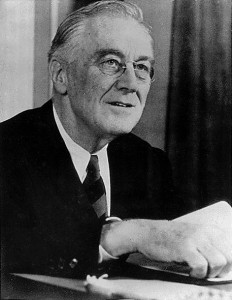

The “San Francisco Conference” Hurley is referring to is the conference that took place in San Francisco, California for two months, from April 25th to June 26th, 1945 at which the United Nations was established. That conference was in progress when Hurley sent his letter to Truman. President Roosevelt, who died on April 12th 1945, did not live to see the United Nations come into being. As noted earlier in this series, Roosevelt himself had encountered British objections to the idea of trusteeships for the nations that had been European colonies before the war from the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, when they met at the Yalta conference [1]in February of 1945. Nevertheless, according to Roosevelt’s last communication with Hurley he still intended that the trusteeships take place, the purpose of which would be to administer the colonial areas until they were able to establish self-government of their own; and that the fledgling UN would be the agency to get them established. (Perhaps Hurley’s letter was his effort to call Roosevelt’s wish to Truman’s attention.) Though the UN charter language ultimately agreed upon is very supportive of the concept of self-determination for colonial peoples; and though it did establish a “Trusteeship Council”, the nascent United Nations stopped short of establishing trusteeships over many of the main European colonial areas, Vietnam among them. As a result, when the Potsdam Conference [2]was held in Germany in July/August of 1945 Vietnam ended up being returned to the French.

Nearly two months before Hurley’s letter to Truman, even before the German surrender on May 9th, 1945 ending World War II in Europe, the first hints of what would become the Cold War appeared in a policy paper published on April 2nd by the US Office of Strategic Services.[3] Most likely, when he came into office following Roosevelt’s death on April 12th, Truman had no idea of the OSS paper, which stated that the Russians seemed to be seeking to dominate the world, and recommended that the US take steps to block Russian expansionism. Unfortunately, before long these concerns over Soviet expansionism would become the focal point of US foreign policy, overwhelming and trumping any US concerns regarding self-determination of colonial peoples.

As the events in Vietnam covered earlier in this series moved forward across 1945 and 1946, so did the pre Cold War chill continue to develop between the United States and the Soviet Union. In February of 1946, in response to a request from the US State Department for an analysis of Soviet Union post war attitudes, an assistant US Ambassador to the Soviet Union named George Kennan sent what is now a somewhat famous telegram[4] to Secretary of State George Marshall [5]that was very critical of the Russians. In the telegram Kennan stated that the Soviets were very resistive to assisting the US in the re-building of war torn Europe and, in an echo of the earlier OSS, 1945 policy paper, that they had expansionist designs and wanted to spread Communism across Europe and the world. Kennan stated that the Soviets view was that the Western Capitalist system was incompatible with Communism and that as a result the Soviets felt that, “it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our (U.S.) society be disrupted, our traditional way of life be destroyed, the international authority of our state be broken.” After outlining the Communist threat in his telegram Kennan went on to say that US policy should be one of containment of the Soviets and their Communist ideology.

Kennan’s telegram had a huge effect on President Truman and US foreign policy. The anti-Soviet and anti-Communist recommendations embodied in his message actually became the basis of US Cold War strategy and policy as regards the Soviet Union for the bulk of the next four decades. A few weeks after Kennan’s telegram, in early March, 1946, Winston Churchill paid a visit to the United States and President Truman. With Truman he travelled to the President’s home state of Missouri where the former English Prime Minister delivered a speech in which, with reference to the post war actions of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe, he uttered the famous words, “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an Iron Curtain has descended across the continent.”

For many Americans Churchill’s speech, which was widely reported, was the first use of the term “Iron Curtain” they had ever heard. From that point on it would become a catch word of the Cold War, immediately symbolizing to Americans the suppression inherent in the Soviet system. In actual fact, however, the NAZIs in Germany were using the term “Iron Curtain” in a Soviet context as early as February, 1945, when Hitler’s Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels stated in a newspaper article that if Germany lost the war, “An iron curtain would fall over this enormous territory controlled by the Soviet Union, behind which nations would be slaughtered.”

In the first week of May, 1945, right after Hitler committed suicide and right before Germany surrendered, a top remaining NAZI government official named Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk broadcasted a speech in which, with regard to the Soviets, he stated, “In the East the iron curtain behind which, unseen by the eyes of the world, the work of destruction goes on, is moving steadily forward.” Churchill’s first use of the term in a Soviet context dates from just a few days after Schwerin von Krosogk’s speech, when he used it in a telegram to President Truman on May 12th, 1945. It is possible that Churchill and others picked up the term from the NAZI’s and just continued to use it in describing the post war actions of the Soviets.

Be all of that as it may, the above factors by March of 1947 had been coalesced into a U.S. statement of foreign policy called the Truman Doctrine, which more or less was President Truman’s implementation of the recommendations contained in George Kennan’s telegram from the year before. Truman first announced his “doctrine” to a joint session of Congress on March 12th, 1947 in a speech in which he discussed situations in the two Eastern European countries of Greece and Turkey. Greece had been largely devastated by the NAZI occupation in World War II and following the war lacked the resources to re-build. In addition a Communist inspired insurrection had taken place in the northern sector of the country and as a result of these factors the government of Greece was in trouble. To Truman, by extension, if Greece went Communist it would also imperil its neighbor Turkey. Great Britain had been the nation assisting both Greece and Turkey with aid since the end of the war, but now the English, burdened with their own re-building program, could no longer afford to provide assistance. It was into this void that President Truman inserted his Soviet and Communist containment policy called the “Truman Doctrine”, and the United States came to the aid of Greece and Turkey, thus embarking on a world policing role the nation bears to this day.

Many historians date the beginning of the Cold War to Truman’s announcement of his policy in March, 1947, while others date it from Churchill’s “Iron Curtain” speech in Missouri the year before. As can be seen from the above the truth is that the seeds of the Cold War had been sprouting in Europe since even before World War II ended. As one could speculate, Truman’s policy effected how the U.S. dealt with situations in other parts of the world outside of Europe. One of these areas was Vietnam. With the French actions in trying to re-assert their colonial control of Vietnam being opposed by the Vietnamese nationalist Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh, had Truman adhered to Roosevelt’s self-determination principles it would have been reasonable to expect the US to at least provide moral support to the Vietnamese. Instead, since in addition to being a nationalist Ho Chi Minh was also a Communist, the US would end up on the side of the French—a move that ultimately had devastating consequences for our nation.

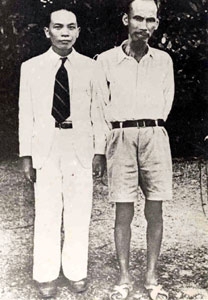

I have given you this brief history of the beginnings of the Cold War so that what was occurring in Vietnam at the same time can be understood within the context of the larger situation being played out in the world. As noted earlier,[6] outright war between the French and the Viet Minh broke out in Vietnam in late 1946. In 1948 the French induced their old puppet emperor Bao Dai [7]to return to the country and in 1949 they officially acknowledged the independence of the State of Vietnam under Bao Dai as an associated state within the French Union. By creating the “independent” State of Vietnam the French were trying to establish a viable political alternative to Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh for the Vietnamese people. It didn’t work and the hopes of the French for a quick victory faded as the conflict continued to drag on for the next several years. It was during this period that the Viet Minh General Võ Nguyên Giáp [8] developed his guerilla style of warfare that would serve him so well nearly a generation later when his forces were battling the Americans in Vietnam. By 1951 there was no end in sight to the French-Vietnamese conflict and, as the Americans would experience when their turn came, the war was becoming a significant drain, both on the French economy and on French national morale.

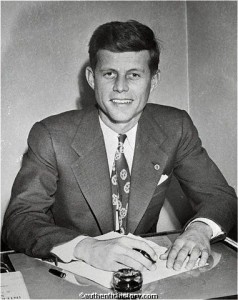

In 1951 the young US Congressman John F. Kennedy, with his younger brother Robert Kennedy in tow, visited Vietnam to take an assessment of the situation. By that time the United States was committed to the Truman Doctrine as the cornerstone of its foreign policy worldwide and was therefore contributing money and equipment to the French effort in Vietnam, as well as military advisors, as part of its Communist “containment” program. While in Vietnam JFK spoke with the commander of the 250,000 man French army in the country who told him that with this overwhelming force there was no way the French could be defeated. In addition to the French commander Kennedy also spoke to his friend and former speech writer, a man named Edmund Gullion, who at that time was an official at the US Consulate in Saigon. What Gullion told Kennedy was quite different from what the French officer had said, and it was something the young Congressman never forgot. “In twenty years there will be no more colonies,” Gullion told JFK. “We’re going nowhere out here. The French have lost. If we come in here and do the same thing, we will lose, too, for the same reason. There’s no will or support for this kind of war back in Paris. The home front is lost. The same thing would happen to us.”

Kennedy returned to the US after his trip to Southeast Asia impressed by what he had seen and heard. At the time, while he felt that it was important to keep Vietnam from becoming Communist, he did not mince words with regard to what he thought of the French and their efforts at re-exerting their control over the area. In a radio address after returning he stated that, “The Indo-Chinese states are puppet states, French principalities with great resources, but as typical examples of empire and colonialism as can be found anywhere. To check the southern drive of Communism makes sense but not only through reliance on the force of arms. The task is, rather, to build strong native non-Communist sentiment within these areas and rely on that as a spearhead of defense. To do this apart from and in defiance of innately nationalistic aims spells foredoomed failure.” He also stated that, “In Indochina we have allied ourselves to the desperate effort of the French regime to hang on to the remnants of empire. There is no broad general support of the native (Bao Dai) Vietnam Government among the people of the area.”[9]

As the next few years demonstrated, Kennedy’s misgivings were well founded. By 1952 the US was carrying, according to some estimates, up to one half the cost of the French war in Indochina,[10] yet no end was in sight. At the same time, beginning in 1950 the United States had become involved in the bloody Korean War against the Communist countries of North Korea and China. Before that war ended in 1953 nearly 40,000 US servicemen were killed and something like 100,000 wounded. (All told it is estimated that, between civilian and military casualties on both sides, the astounding number of 5 million people were killed during the Korean conflict.)

Finally, in the spring of 1954, after nearly eight years of fighting, Viet Minh forces under General Giáp succeeded in trapping the French army at the town of Dien Bien Phu in the northern part of Vietnam, close to the border with Laos and about about 200 miles east of Hanoi. Viet Minh fighters established positions in the high ground around the town and using artillery pounded the French, putting them under siege for over two months. In April and early May a series of assaults by the Viet Minh, though repulsed by the French, seriously weakened the French perimeter, but on May 7th at last succeeded in overrunning the French positions. A few mop up operations remained for the Viet Minh to carry out, but for all intents and purposes that battle of Dien Bien Phu marked the end of the French in Indochina. The First Indochina War was finally over.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2014

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] The “Yalta Conference” was a meeting that took place in February of 1945, a few months before the end of World War II. At the conference, which took place in the town of Yalta in the Crimea, the leaders of the wartime allies, US President Franklin Roosevelt, Prime Minister of Great Britain Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin made plans for the re-organization of Europe following the imminent defeat of NAZI Germany.

[2] The “Potsdam Conference” took place in Germany in July/August of 1945 following the German surrender in May of ‘45. Attending once again were the leaders of the Allied nations, President Harry Truman for the US, Winston Churchill for Great Britain (in the middle of the conference Churchill was replaced by the new Prime Minister Clement Atlee after Churchill’s party was voted out of office) and Joseph Stalin of the Soviet Union. The purpose of the Conference was to work out agreements on the handling of Germany and post war Europe and also resulted in an ultimatum to Japan for unconditional surrender or face total destruction. A few days after the conference the US dropped nuclear weapons on Japan which brought WW II to a close.

[3] The “Office of Strategic Services” was the United States World War II intelligence agency formed in 1942 to fill the US need for gathering and coordinating intelligence and conducting secret operations during the war. It was formed with the assistance of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), also known as MI 6, and was patterned after it. Though the OSS was disbanded following World War II many of its operatives formed the nucleus of what would become the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) once it was created in 1947.

[4] Due to its length, George Kennan’s telegram to US Secretary of State George Marshall depicting the Soviet threat to the West has become known as “the long telegram”. Rarely in history has a document produced by a relatively minor bureaucrat produced such a significant effect as Kennan’s telegram.

[5] General of the Army George Marshall was Chief of Staff of the US Army during World War II and in that role was the chief military advisor to President Roosevelt during the war. As Secretary of State following the war he helped to create “The Marshall Plan” as a strategy to assist the destroyed nations of Europe to recover economically and get back on their feet.

[6] Please see Part II of “JFK and the Road to Dallas: Ramping Up the Vietnam War” earlier in this blog site.

[7] For more information on Bao Dai please see Part II of “JFK and the Road to Dallas: Ramping Up the Vietnam War” earlier in this blog site.

[8] General Võ Nguyên Giáp was a General in the Vietnamese Viet Minh army who rose to prominence during the fight against Japan during World War II. He also led the Viet Minh in the First Indochina War against France and later against South Vietnam and the United States in the Vietnam War.

[9] From a statement made by JFK in 1951 and quoted in his 1960 book “A Strategy for Peace”.

[10] This estimate was made by US Secretary of State Dean Acheson in 1952 and was quoted in the book “Mission to Hanoi” by Harry S. Ashmore and William C. Baggs published in 1968

Tracking ID

2 Responses

Good stuff, Arnoldian. I think it was pro-survival to salvage Greece, but obviously, as we have discussed numerous times, U.S. support of European colonial powers against the national aspirations of native populations, coupled with U.S. support of tyrannical dictators rather than the oppressed in Latin America, as well as our support of puppet regimes that failed to acquire legitimacy with their own people, as in South Vietnam under Diem, was utterly disastrous. It’s as if no one occupying the presidency was a student of history, whether world history or our own.

Pendleton!

Thanks for the comments. Your point about the lack of grasp of history and the misplaced support of dictators by Presidents and the Government is well taken. I am sending you an e-mail about some interesting data I am finding and will get it to you soon. Please get back to me as soon as you can after you read it.

Thanks Pendleton!

Arnoldian