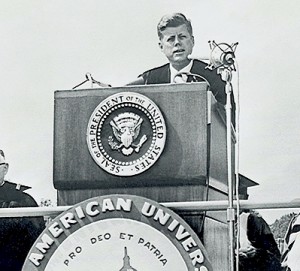

Note: On June 10th, 1963 John Kennedy delivered the most important speech of his Presidency and arguably of any by an American President since Franklin Roosevelt; his “Peace Speech” at American University in Washington DC. Considering the anti-communist era it was delivered in the speech was stunning in its empathy for our Cold War enemy the Soviet Union and for its emphasis on the need for Americans to be willing to re-examine their own notions about war, peace, the Soviet Union and injustices here at home. Born out of the efforts of a dying Pope and a peace activist journalist to help Kennedy and Khrushchev find common ground and end the arms race, the speech represented a bold, new approach to Soviet-American relations…Here is the whole story of John Kennedy’s “Peace Speech” at American University…MA

_______________________________________

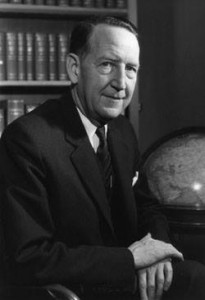

On April 22nd, 1963, ten days after his visit with Nikita Khrushchev at the Soviet leader’s Black Sea retreat,[1] Norman Cousins was in Washington DC to report on the meeting to President Kennedy. The day was an unusually busy one, even for the President. On arriving Cousins had to wait in the Cabinet room for twenty minutes while JFK completed a ceremony with the Commissioner of Education honoring the teacher of the year. In a short while on the White House lawn he was scheduled to speak at a musicale of high school student musicians for which busloads of the teenagers were, at that moment, arriving. The event had been scheduled by the First Lady but for some reason she was away from the White House, so the host and speaker duties had fallen to the President. In between the two events JFK had time to debrief Cousins on his trip.

On exiting from the teacher ceremony the President greeted Cousins and directed him into his office.

“I understand you had a good meeting with Chairman Khrushchev,” Kennedy said. “It was at his place on the Black Sea, wasn’t it?

Cousins nodded in agreement.

“Is it as nice as they say?” the President inquired.

Cousins proceeded to tell Kennedy about the tour of the grounds Khrushchev had conducted, the gymnasium and the glass enclosed swimming pool, as well as the main house. He also told the President about his badminton game with Khrushchev and how after 10 minutes of playing the Premier wasn’t even winded.

JFK was impressed, commenting that it sounded as if the Soviet leader was in good condition.

“I trust you didn’t win,” the President added.

“It never really came to that,” Cousins said. “Khrushchev gave me instructions. He was swatting the bird and wanted me to do the same.”

His curiosity about his Soviet counterpart’s Black Sea retreat satisfied, the President got down to business. He was very interested to know Khrushchev’s reaction to the message he had asked Cousins to relay to the Chairman: that the United States genuinely wanted the Test Ban treaty and that Kennedy believed there had been an honest misunderstanding on the issue of the number of inspections.

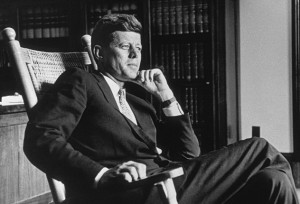

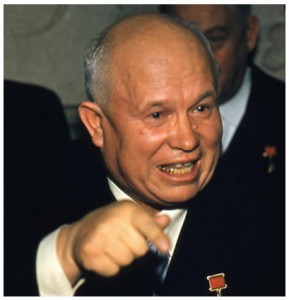

As Kennedy sat quietly in his rocking chair listening, Cousins, quoting frequently from the notes he took while talking to Khrushchev, told the President of his long conversation with the Soviet leader. With regard to the Test Ban treaty, Cousins spoke of the assurances that Khrushchev had given his Council of Ministers that the United States had agreed to three inspections and of the betrayal he felt when this turned out to be not true. Cousins emphasized to the President that Khrushchev felt he had been made to look foolish by the incident and that the Chairman had assured him that it would not happen again. He also told JFK of the pressure on Khrushchev within the Soviet Union to adopt a hard line relative to the United States. Despite all of these factors, Cousins relayed to the President, Khrushchev had ultimately become willing to accept the explanation of an honest misunderstanding as regards the number of inspections and was willing as well to make a fresh start in the negotiations. But, Cousins emphasized, the Chairman insisted that the first overture in that direction would need to come from the United States.

Cousins paused in his discourse and the President took the opportunity to respond to what he was being told:

“You know, the more I learn about this business,” he said, “the more I learn how difficult it is to communicate on the really important matters…One of the ironic things about this entire situation is that Mr. Khrushchev and I occupy approximately the same political positions inside our governments. He would like to prevent a nuclear war but is under severe pressure from his hard-line crowd, which interprets every move in that direction as appeasement. I’ve got similar problems. Meanwhile, the lack of progress in reaching agreements between our two countries gives strength to the hard-line boys in both, with the result that the hard-liners in the Soviet Union and the United States feed on one another, each using the actions of the other to justify its own position.”

Kennedy continued on, saying that the problem was complex but that a way was needed to solve it. He told Cousins that he was pleased to hear of Khrushchev’s willingness to re-engage newly in the Test Ban negotiations and stated this time he wanted Averell Harriman as the point man for the U.S. side. Harriman had successfully conducted the Laos neutrality negotiations for JFK in 1961-62 and was well regarded and respected by the Soviets. (for a description of the Laotian crisis please see “JFK and the Road to Dallas:Laos–The Vietnam that Never Was” earlier in this series.)

The President also indicated that he understood Khrushchev’s position with the Council of Ministers:

“He’s on the spot,” Kennedy said, “but I don’t see how we can cut down on inspections. We’d never get it through the Senate. As it is, we’ll have a real battle on our hands to get a treaty through the Senate even if the Russians agreed to everything we asked. Maybe we can find some way around the impasse on underground inspections.”

The President then indicated that he would like for Cousins to meet with Dean Rusk when the Secretary of State was back in Washington the following week. He also wanted Cousins to meet that afternoon with two other key officials who were knowledgeable about the Test Ban negotiations. He picked up his phone and asked his secretary to connect him with the former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn E. (Tommy) Thompson and William C. Foster, the chief of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Within a few minutes the President had arranged appointments for Cousins with both. He wanted them to have the information Cousins had brought back from the Soviet Union.

The appointments made, Kennedy turned back to Cousins and told him that his description of Khrushchev’s difficulties in getting the rest of the Soviet leadership to come along on the Test Ban issue confirmed what the President had been thinking for some time; that Khrushchev, far from being in a position of absolute power, had his own issues in getting his programs accepted.

Cousins then further enlightened Kennedy on the situation in the Soviet Union. He told the President that the evidence seemed to indicate that a political crisis was developing in Russia and that at the core of it was almost certainly the Test Ban issue. Khrushchev was staking a great deal on his peace initiative with the United States. If he succeeded it would mean that the Soviet Union could scale down its arms industry and put more energy and resources into the production of consumer goods, thereby expanding the nation’s economy and improving the living standards of the people. If he failed it would mean more than just the opposite. It would mean, as well, the strengthening of the hard-line position, not just in the Soviet Union, but in the entire Communist world and most specifically Communist China. The Chinese, Cousins said, were a major source of criticism of Khrushchev, stating that he was violating the sacred tenets of Marx and Lenin in trying to peacefully co-exist with the West. If Khrushchev failed in achieving a Test Ban treaty, the failure would be used by the Chinese to illustrate just how unrealistic it is to try and negotiate with the Capitalists. The Chinese, Cousins continued, had most likely already written off the Test Ban treaty as not possible and believed that the Soviet Union would soon be making a public announcement to that effect. Their hope was that this would strengthen their ties to the Soviets while severing the fragile hopes of peaceful co-existence that had developed between Moscow and Washington since the Cuban Missile Crisis. The Chinese were actively moving forward on this assumption of failure and were planning on sending a high-level delegation to Moscow in early June to reinforce their case.

Kennedy took in all that Cousins was saying and told him that he understood that Soviet-Chinese relations were complicated. Some things, the President said, were beyond our reach or power, but one thing that might be within reach was the improvement of American-Soviet relations.

On hearing the President’s words Cousins then made a bold proposal. As he reports in his book “The Improbable Triumvirate” he told the President that,

“… perhaps what was needed was a breathtaking new approach toward the Russian people; an approach that called for an end to the Cold War and a fresh start in American-Russian relationships. Such an approach might recognize the implications of a world that had become a single unit, however disorganized; it might recognize, too, that the old animosities could become the fuse of a holocaust.”

The President sat back and lit a cigar. He said that he wanted to think about it and asked Cousins to prepare for him a memorandum on the subject. Cousins said he would.

The two men then discussed other aspects of Cousins’ visit with Khrushchev, particularly the Chairman’s critical views of American society and culture and the facts and figures Cousins had used to counter the Soviet leader’s claims. Some of this information caught Kennedy’s attention, but not for the reasons one would think. During their visit, when Khrushchev claimed that America was a nation of comic book readers and that TV was degrading American youth, Cousins had countered with the fact that more than 300 million actual books, not comic books, had been sold in the U.S. in the last year and that one child in three was taking music lessons.

This prompted Kennedy to state:

“If you have any statistics about the state of American culture, I wish you would give them to me. In about half an hour I’ve got to go out on that lawn and say something to those high school kids. Jackie’s in Florida and I’ve got to look after her music party…I don’t have to talk more than ten minutes. Do you think you could jot down a few notes for my talk at one o’clock?”

Cousins looked at his watch noting that it was, at that moment, twelve thirty-five. The President had to speak in twenty-five minutes meaning Cousins had twenty minutes at the outside to “jot down a few notes.” Kennedy told Cousins that his secretary Mrs. Lincoln [2] would assist him with whatever he needed, which turned out to be a typewriter and a telephone. Cousins then phoned his office in New York and relayed to his secretary the cultural facts and figures he required and gave her six minutes to call him back with the data. He then went to work on the President’s talk, leaving spaces to insert the facts he would soon receive. The secretary called back right on time and Cousins inserted the data and completed the notes for the talk. The time was 12:51 PM.

Cousins handed the notes to an aide for delivery to the President and then was escorted into the White House dining room for lunch. A couple minutes later JFK aide Kenny O’Donnell joined Cousins at the table.

“Now I’ve seen everything,” O’Donnell said. “The President had seven minutes before he was due to speak. He raced down to the White House pool, tore off his clothes, dove in, and swam with one hand. In the other hand he was studying the draft of the talk you gave him for the kids.”

After lunch Cousins kept his appointments with Tommy Thompson and William Foster as the President wished. His talks with both men confirmed much of what Cousins had concluded from his talks with Khrushchev; that the United States needed to move fast to get the Test Ban talks moving again and that something dramatic was needed to help Khrushchev succeed in bringing the rest of Soviet leadership along with him in his quest for peaceful co-existence. As the Chairman had stated, the next move was up to Kennedy. Failure to accomplish this now could well mean that Khrushchev would be overwhelmed by the hard line elements in his government and the window for peace would close.

Accurately sensing the precariousness of the situation, Cousins returned to New York that evening and the next morning, as the President had requested, prepared a memorandum that outlined the main points he had discussed with Kennedy, particularly emphasizing the fact that the Chinese intended to arrive in Moscow in early June to press their case for a hard-line approach to the Americans. He also stressed the need for a Kennedy initiated bold, new approach to Soviet-American relations. What Cousins had in mind for this bold approach is best explained by the actual text of the memorandum:

“The moment is now at hand for the single most important speech of your Presidency. It should be a speech which, in its breathtaking proposals for genuine peace, in its tone of friendliness for the Soviet people and its understanding of their ordeal during the last war, in its inspired advocacy of the human interest, would create a world groundswell of support for American leadership…More than anything else, it would create a whole new context for the pursuit of peace. I doubt that there is any issue that reaches more deeply into the American people—indeed all peoples—than this.”

Cousins forwarded the memorandum to the White House and then, well aware that the clock was ticking and that time was short, returned to his post as Editor of Saturday Review and tried to get some work done.

Two weeks went by before Cousins received any acknowledgement from the President with regard to his memorandum. Finally a phone call came from the White House. On the other end of the line was the President’s assistant and chief speech writer Ted Sorensen. The President, Sorensen said, had asked him to consult with Cousins on the text of an upcoming speech and he wanted Cousins to come to Washington as soon as possible for this purpose. On arriving at the White House Sorensen told Cousins that he had received the memorandum from JFK. The President felt, Sorensen said, that the Russian-Chinese rift was sufficiently severe that it would not be affected, even by a failure of the Test Ban talks. But, he added, the President also felt that if the Soviet leadership was ready for agreements leading to a real peace then the opportunity ought to be pursued. To that end Kennedy intended to use a commencement talk he planned to deliver at American University on June 10th, 1963 for the purpose of publicly discussing the subjects of disarmament and peace. The President had decided to move on Cousins’ suggestion from two weeks earlier that a bold, new approach was needed to the problem of Soviet-American relations. Sorensen told Cousins that JFK thought some of the points in the memorandum and some of the points Cousins and the President had discussed two weeks earlier could possibly be incorporated into the text of the talk. Excited at the prospect, Cousins thanked Sorensen and said he would forward his ideas in a few days. He then left for New York.

Meanwhile in the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev had not been idle. Following Norman Cousins’ visit in early April the Chairman had made arrangements to have Cuban leader Fidel Castro come to the Soviet Union for what would turn out to be a month long stay in May of 1963. Castro had been very upset at the way in which the Cuban Missile crisis was resolved. When the Soviets decided to withdraw the missiles from his island he was not consulted. Thus, without his knowledge or agreement, he had lost what he considered his best deterrent to an American invasion. With the Chinese accusing him of abandoning Cuba, Khrushchev felt the need to repair the rupture with his Cuban ally. He spent the month taking Castro on a friendship tour of the Soviet Union while at the same time educating him that the decision to remove the missiles was the right thing to do because the peace had been preserved. According to Castro himself:

“…(Khrushchev) for hours read many messages to me, messages from President Kennedy, messages sometimes delivered through Robert Kennedy…There was a translator and Khrushchev read and read the letters back and forth.”

The Soviet leader was trying to give Castro a sense of Kennedy’s humanity and trustworthiness. According to Sergei Khrushchev, the Soviet Premier’s son:

“Father tried to persuade Castro that the U.S. president would keep his word and that Cuba was guaranteed six years of peaceful development, which was how long Father thought Kennedy would be in the White House. Six years! Almost an eternity!”

Ultimately Castro decided to follow Khrushchev’s advice. Even the CIA acknowledged this. In a secret memo dated June 5th, 1963 covert op chief Richard Helms noted that, “at the request of Khrushchev, Castro was returning to Cuba with the intention of adopting a conciliatory policy toward the Kennedy administration…”

A positive development with regard to the potential Test Ban treaty occurred on May 27th when two U.S. Senators, Thomas Dodd of Connecticut and Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota introduced a Senate resolution that called for a Test Ban treaty that banned atmospheric testing only, thus bypassing the issue of inspections on underground testing. While in the past Khrushchev had insisted on a treaty on all nuclear testing, or none at all, the fact was that the resolution provided a clever way around the inspection issue while still accomplishing some form of a treaty. It also demonstrated to Kennedy that there would be support in the Senate for at least a limited treaty, which, as he approached his date at American University, was a hopeful sign.

On top of this came another hopeful development. Averell Harriman had returned from a visit to Moscow confirming that Khrushchev was indeed willing to re-open the Test Ban negotiations.

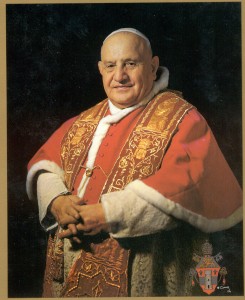

Despite his good work at making it possible, Pope John XXIII would not live to see or hear what would be the most significant major step yet toward the vision of world peace he had described in his “Pacem In Terris” [3] encyclical: the stunning speech soon to be delivered by JFK at American University. On June 3rd, 1963 the Pope succumbed to his cancer. He died feeling that in writing and publishing “Pacem In Terris” he had done far too little in the cause of world peace and was haunted by the possibility that mankind would once again be subject to the devastation of world war. In reality the Pope, as a result of his encyclical and his peace emissary Norman Cousins, was on the verge of achieving far more than he realized at the time of his demise.

On June 10th, 1963, one week after Pope John’s death, President Kennedy took the podium to deliver his commencement address to the graduating class at American University. At the same time the official Communist Chinese delegation was arriving in Moscow bent on exploiting the expected failure of the Test Ban talks to restore a Soviet hard line toward the West. The Chinese had issued an open letter to the Russian people that as yet had not been published by the Soviet government. The letter was a statement of the Chinese view that the Soviet Union should return to what they viewed as the strict principles of Marx and Lenin which they saw as being violated by Khrushchev’s efforts at peaceful coexistence with the United States. It was against this Soviet backdrop of Chinese counter-effort to Khrushchev’s co-existence policy with the West that President Kennedy delivered his speech.

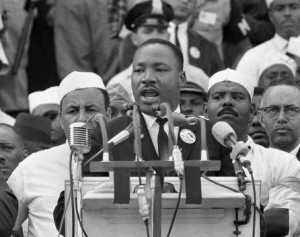

Kennedy’s “peace” speech at American University was, in my opinion, at once the best and most significant of his career and rivals Martin Luther Kings’s “I Have A Dream”[4] speech as the best American speech by a public figure since World War II. Reading or watching it today, while the taint of Cold War ideology is still clearly apparent in its text, one is struck by several elements in it that mark it as a radical departure from any Cold War speech ever delivered by an American President. The first is his description of what he means when he speaks of world peace:

“What kind of peace do I mean? What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living, the kind that enables men and nations to grow and to hope and to build a better life for their children—not merely peace for Americans but peace for all men and women. Not merely peace in our time but peace for all time.”

The attainment of the peace thus described, Kennedy goes on to say, starts with an examination of our own attitudes about peace:

“…Too many of us think it is impossible. Too many think it is unreal. But that is a dangerous, defeatist belief. It leads to the conclusion that war is inevitable—that mankind is doomed—that we are gripped by forces we cannot control…We need not accept that view. Our problems are man made—therefore, they can be solved by man. And man can be as big as he wants. No problem of human destiny is beyond human beings. Man’s reason and spirit have often solved the seemingly unsolvable—and we believe they can do it again.”

And then, while stating that from the American view Communism is a repugnant system, he displays an empathy and respect for the Russian people never before acknowledged by an American leader. Borrowing from parts of “Pacem In Terris” Kennedy continues:

“No government or social system is so evil that its people must be considered lacking in virtue. As Americans we find communism profoundly repugnant as a negation of personal freedom and dignity. But we can still hail the Russian people for their many achievements—in science and space, in economic and industrial growth, in culture and in acts of courage…Among the many traits the peoples of our two countries have in common, none is stronger than our mutual abhorrence of war. Almost unique among the major world powers, we have never been at war with each other. And no country in the history of battle ever suffered more than the Soviet Union in the Second World War. At least 20 million lost their lives. Countless millions of homes and farms were burned or sacked. A third of the nation’s territory, including two thirds of its industrial base, was turned into a wasteland—a loss equivalent to the destruction of this country east of Chicago.”

The President makes the point in his speech that should war break out again, the United States and Soviet Union would be the primary targets; ironic since they are the two most powerful nations. He goes on to point out that should war come to pass;

“All we have built, all we have worked for, would be destroyed in the first 24 hours.”

He then speaks of the effect of the Cold War on the two nations as follows:

“And even in the Cold War, which brings burdens and dangers to so many countries, including this nation’s closest allies—our two countries bear the heaviest burdens. For we are both devoting massive sums of money to weapons that could be better devoted to combat ignorance, poverty and disease. We are both caught up in a vicious and dangerous cycle, in which suspicion on one side breeds suspicion on the other, and new weapons beget counter-weapons.”

With regard to the mutual responsibility shared by the United States, the Soviet Union and the allies of both nations for creating a genuine peace, Kennedy sums up as follows:

“In short, both the United States and its allies, and the Soviet Union and its allies, have a mutually deep interest in a just and genuine peace and in halting the arms race…So let us not be blind to our differences—but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved. And if we cannot end now our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity. For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s futures. And we are all mortal.”

Kennedy then used the speech to make two significant announcements:

“First: Chairman Khrushchev, Prime Minister Macmillan, and I have agreed that high-level discussions will shortly begin in Moscow looking toward early agreement on a comprehensive test ban treaty…Second: To make clear our good faith and solemn convictions on the matter, I now declare that the United States does not propose to conduct nuclear tests in the atmosphere so long as other states do not do so. We will not be the first to resume. Such a declaration is no substitute for a formal, binding treaty, but I hope it will help us achieve one. Nor would such a treaty be a substitute for disarmament, but I hope it will help us achieve it.”

In closing his speech JFK called on all Americans to examine their attitudes towards peace and freedom at home:

“But wherever we are,” the President said, “we must all, in our daily lives, live up to the age-old faith that peace and freedom walk together. In too many of our cities today, the peace is not secure because freedom is incomplete.”

He then referred to the responsibility of the various branches of government at local, state and national levels to provide and protect freedom for all citizens and the responsibility of all citizens to respect the rights of others. Calling again from the principles Pope John described in “Pacem In Terris”, JFK made a powerful closing appeal to his fellow citizens:

“All this is not unrelated to world peace,” Kennedy said. “‘When a man’s ways please the Lord,’ the Scriptures tell us, ‘he maketh even his enemies to be at peace with him.’ And is not peace, in the last analysis, basically a matter of human rights—the right to live out our lives without fear of devastation—the right to breathe air as nature provided it—the right of future generations to a healthy existence?…While we proceed to safeguard our national interests, let us also safeguard human interests. And the elimination of war and arms is clearly in the interest of both…This generation of Americans has already had enough—more than enough—of war and hate and oppression. We shall be prepared if others wish it. We shall be alert to try to stop it. But we shall also do our part to build a world of peace where the weak are safe and the strong are just. We are not helpless before the task or hopeless of its success. Confident and unafraid, we must labor on—not toward a strategy of annihilation but toward a strategy of peace.”

With his “peace” speech at American University John Kennedy had, indeed, and as Norman Cousins had hoped he would, inaugurated a bold new approach to the problem of Soviet-American relations and world peace. For the few months Kennedy had left in his life, and due to the efforts of his counterpart in the Soviet Union, a now deceased Pope, an American journalist, and the President himself, the prospects for a genuine peace in the world, at least for the moment, had taken on a much more hopeful aspect.

To be continued…

________________________________________

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] For a description of Norman Cousins’ visit with Khrushchev at the Soviet leader’s Black Sea estate please see “Improbable Peace Makers” Part III earlier in this series. MA

[2] Evelyn Lincoln was John Kennedy’s secretary from the date of his election to the U.S. Senate in 1953 until his assassination in 1963.

[3] The Pope’s encyclical “Pacem In Terris” (Peace On Earth) is discussed in “Improbable Peace Makers” Part III earlier in this series…MA

[4] MLK’s “I Have A Dream” speech was delivered August 29th, 1963, just two and a half months after Kennedy’s address at American University. The occasion was the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” which drew nearly 300,000 people to the nation’s capital.

2 Responses

I was not at all interested in History when I was back in school, but you and others like you bring it to life and spark my interest.

It is never too late to learn, and so I am!

Thank you for writing!

Tony

Thanks Tony! So glad your interest is sparked. You are so right…never too late to learn.

Say Hi to Helen for me ….L Mark