JFK signs Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, October 7, 1963

Introduction

November 22nd of this year will mark the 60th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy; an event that is nothing less than a watershed moment for our country. The dictionary defines the term “watershed” as, “a crucial dividing point, line, or factor ; a turning point.” To understand why Kennedy’s murder is one of those, it is important to grasp one of the key principles of the art of investigation, something called “date coincidence.” This is a tool used by administrators to help discover the cause of sudden statistical expansions or contractions; or by law enforcement to investigate a crime and discover who did it. In administration, for instance, an executive may note that sales have been consistently improving over the last few weeks. While investigating the improvement, the exec would note through statistical analysis that the sales started picking up exactly five weeks earlier. This would indicate that whatever is causing the sales expansion would be a change or program implemented shortly before or at that point. So, the exec investigates for changes during that period, and finds that a new sales manager was hired who initiated a program to enhance salesman skills. The executive has now discovered the reason for the expansion. Similarly, a policeman trying to find what is causing an uptick in drug trafficking in his city, would use “date coincidence” by studying out the situation with an eye toward answering the question: “when did drug trafficking in our city start getting worse?” By investigating records of arrests and overdoses, he notes that both started to dramatically rise six months earlier. He then starts investigating that period for changes, and discovers that a new gang arrived and established itself in his city at that time. Many of the new trafficking arrests involved members of that gang. He then investigates the gang and discovers that they came from LA and brought with them a heroin smuggling operation from Mexico. The policeman has now discovered the cause of increased drug trafficking in his city.

JFK Turns Toward Peace

Now, let’s look at this “date coincidence” principle in application to the JFK assassination and the Vietnam War. Research of the last year of Kennedy’s life shows that as president he was making significant progress in defusing the Cold War with the Soviet Union AND toward ending U.S. involvement in Vietnam. With the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis by Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev in late October, 1962, the world had narrowly averted a nuclear war that would have killed 100s of millions around the planet. Not wanting to risk such a situation again, Kennedy began to try and reinvigorate the stalled negotiations on a nuclear Limited Test Ban Treaty[1] with the Soviets. Through the good offices of Pope John XXIII and his handpicked representative, a pacifist, Catholic magazine publisher named Norman Cousins, back channel negotiations were initiated with Khrushchev that resulted in a raised Soviet willingness to resume the talks.[2] A short while later (June 10, 1963) Kennedy surprised the cold warrior establishment in his own government by delivering what is now called his “Peace Speech” at American University, in which he urges Americans to re-think their attitudes about the Soviet Union and the possibility of world peace. One of the greatest speeches by an American President in the 20th century, Kennedy’s oration is stunning in both elegance and effect. Shortly after this the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain resumed negotiations on the nuclear Limited Test Ban Treaty, and within a few weeks the three nations had resolved their difficulties and come to agreement on the treaty. In the United States, agreeing on a treaty is the easy part; it must also be ratified by the Senate, and with the Cold War “think” of the times that would be easier said than done. Undaunted, across the last weeks of summer, 1963, the Kennedy administration launched a major lobbying effort, which resulted, on September 24, 1963, in the Senate passing the treaty by a landslide vote of 80-19.

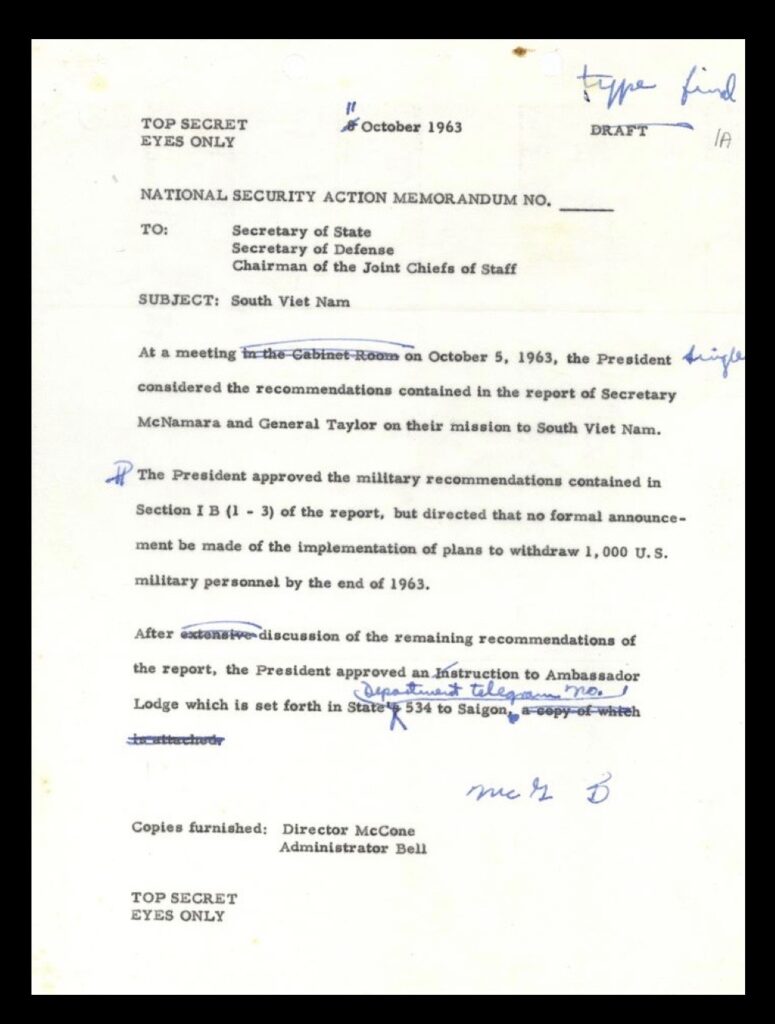

The Test Ban Treaty accomplished, JFK then turned his attention towards winding down U.S. involvement in Vietnam. By the fall of 1963 there were about 16,000 U.S. military personnel in Vietnam, mostly advisors, and no combat troops; at that point the total number of U.S. military personnel killed in country during all the years of direct U.S. involvement there (since 1954) was less than 200. Actually, behind the scenes JFK had been moving in the direction of withdrawal for some months, and on 11 October, 1963, those efforts culminated in his approving National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM)[3] 263, which mandated the removal of 1000 American military personnel from Vietnam by the end of 1963, and all American military personnel out by 1965.

And so, if one just steps back and looks at the pattern of events across 1963, President Kennedy’s intentions become clear. In June of that year he delivers his Peace Speech, which is followed in July by the resumption of negotiations on the Limited Test Ban Treaty. The Treaty is agreed upon in late July by the United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain, and is passed by the U.S. Senate in late September, which is then followed by NSAM 263 on October 11. Seeing these things, one need not be a soothsayer to divine that Kennedy intended to withdraw from Vietnam and likely intended to end the Cold War. Seeing these things as well, however, were the Cold Warrior elements in the Pentagon, the CIA and the U.S. National Security establishment, and, as subsequent events would show, they would not take these changes lying down. The stage was rapidly being set for Dallas, but another major event would shortly take place that would have a huge effect on our nation’s tragic and heartbreaking involvement in Vietnam.

Ngo Dinh Diem and NSAM 273

On November 2, 1963, South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem[4], the only president South Vietnam had ever known, was murdered in Saigon during a coup d’etat. The killing of Diem and the advent of a new regime prompted a reappraisal of U.S. policy for South Vietnam, and to that end a Secretary of Defense (SecDef) conference was held in Honolulu on November 20, two days before Kennedy was killed. At this conference the Joint Chiefs of Staff[5] and Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV)[6] presented a bleak view of the war, describing it as failing, thus reversing a nearly two year-long pattern of couching the war in optimistic terms. In his writings on this crucial period in our history, researcher, author and retired US Army Major John Newman[7], comments on this as follows:

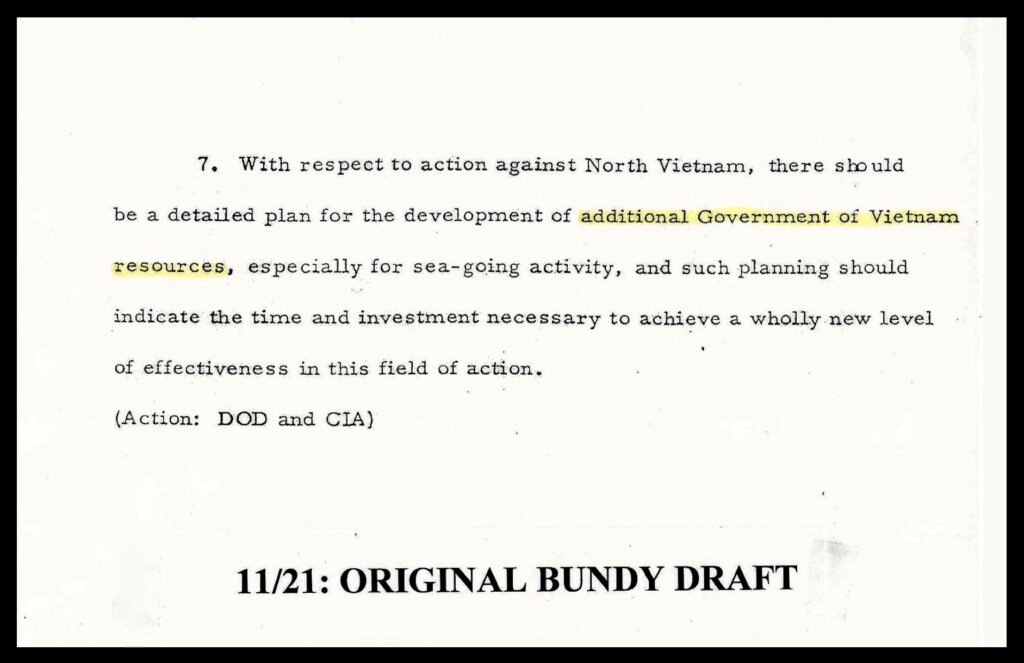

“The Joint Chiefs of Staff and Military Assistance Command Vietnam responded to Kennedy’s withdrawal plan by telling the truth about the failing war effort at the 20 November, 1963 SECDEF conference in Honolulu. The chiefs had no intention of letting JFK pull out of Vietnam in a winning scenario and wanted to diminish his chances of winning the 1964 election. This marked the end of the false optimism the military had begun in February 1962, a stunning reversal that required new recommendations be presented to the president for a new National Security Action Memorandum—NSAM 273. After returning to the White House from the conference on 21 November, National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy[8] prepared the original draft the day before Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The military’s recommendations in Honolulu included widening the war effort, including actions against North Vietnam. In an interview with me, Bundy said that he tried to bring these recommendations ‘in line with the words Kennedy might want to say.’”

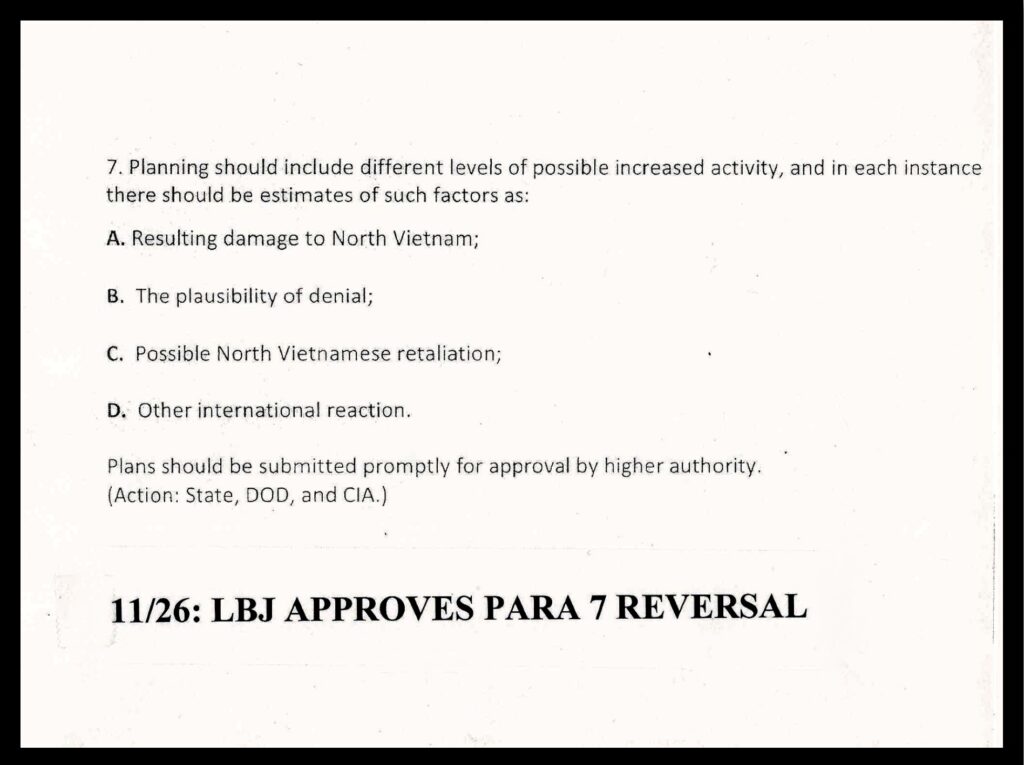

Newman goes on to say that, “the key paragraph in this NSAM was the seventh, as it addressed actions against North Vietnam. Knowing well the president’s aversion to direct American intervention in the Vietnam War, Bundy considerably watered down the military’s agenda proposed at the Honolulu conference—OPLAN 34-63.[9] That plan included a large number of actions against North Vietnam, including U.S. airstrikes and naval raids against the coastline. To bring an intensification of the war in line with the president’s views, Bundy constrained any new actions against the North to be carried out only ‘with additional government of Vietnam resources.’”

In other words, Bundy knew that Kennedy would never approve the Chief’s OPLAN 34-63 actions by the U.S. military, and so, on November 21, in paragraph seven of NSAM 273, he rewrote these actions as being carried out by the government of South Vietnam. Had those provisions remained as Bundy wrote them, it’s possible the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam would have been vastly different.

Epilog

On November 22, while on a political trip to Texas, JFK was assassinated in Dallas. Thus, when it came time to approve the final wording of NSAM 273, the task fell to the new president, Kennedy’s former vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson. On November 24, while Kennedy’s body lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda, President Johnson ordered Bundy to completely strike paragraph seven and rewrite it to allow direct American military attacks against North Vietnam—in other words, reinstate the military’s OPLAN 34-63 directives. Bundy complied with the order, and LBJ approved the new version of NSAM 273 on 26 November. The first American navy “Desoto” patrols[10] along the North Vietnamese coast began a few weeks later, and in the summer of 1964 these actions provoked the Tonkin Gulf Crisis[11] and the passage of a congressional resolution permitting LBJ to do whatever was necessary to defeat North Vietnam.

And so, the Vietnam War started for real, and now you know its “date coincidence”; an altered seventh paragraph of NSAM 273, ordered by Lyndon Johnson and approved by him on 26 November, 1963, four days after President Kennedy was murdered on the streets of Dallas.

[1] For the remarkable, full story of the Limited Test Ban Treaty please see this blog post at fromanativeson.com: https://fromanativeson.com/2013/11/19/jfk-and-the-road-to-dallas-the-limited-test-ban-treaty-by-mark-arnold/

[2] For the full story of Pope John XXIII, Norman Cousins and their successful back channel negotiations with JFK and Khrushchev, please go to fromanativeson.com and see the blog posts “JFK and the Road to Dallas: Improbable Peace Makers”-Parts I, II, III

[3] NSAM is an acronym for “National Security Action Memorandum,” which are fundamentally policy directives issued by the National Security Council. The United States National Security Council (NSC) is the principal forum used by the president of the United States for consideration of national security, military, and foreign policy matters. Based in the White House, it is part of the Executive Office of the President of the United States, and composed of senior national security advisors and Cabinet officials. Since its inception in 1947 by President Harry S. Truman, the function of the Council has been to advise and assist the president on national security and foreign policies. It also serves as the president’s principal arm for coordinating these policies among various government agencies. The Council has subsequently played a key role in most major events in U.S. foreign policy, from the Korean War to the War on Terror.

[4] Ngo Dinh Diem (1901-1963) was born into an aristocratic, Roman Catholic family in Vietnam. He served in Emperor Bao Dai’s administration under French colonial rule until 1933, and during and after World War II he opposed both French colonial rule and the communist–led national independence movement (the Viet Minh). The staunchly anti-communist Diem rejected an offer to serve in Ho Chi Minh’s brief postwar government in 1945. As the Viet Minh battled the French in the First Indochina War for Vietnamese independence, Diem spent several years in exile making political contacts and gaining American support in hopes of leading a Vietnamese government once the French were gone. He became prime minister of South Vietnam in 1954 just as the defeated French forces were leaving. The Geneva Accords of 1954, which temporarily divided Vietnam into northern and southern zones, called for elections in 1956 to reunite the country, but, knowing that Ho Chi Minh would have easily won the presidency, Diem cancelled the elections. Over the next seven years he presided over an increasingly corrupt and autocratic regime. Communist guerillas backed by North Vietnam launched an insurgency in the south that expanded across the late 1950s and early 1960s, but a civil disobedience campaign led by the country’s Buddhist monks contributed more directly to his downfall. Brutal persecution of the dissident monks in 1963 damaged the regime’s already shaky international reputation. With American support, Vietnamese generals overthrew and assassinated Diem later that year.

[5] The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, which advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the National Security Council on military matters. The composition of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is defined by statute and consists of a chairman (CJCS), a vice chairman (VJCS), the chiefs of the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, Space Force, and the chief of the National Guard Bureau. Each of the individual service chiefs, outside their JCS obligations, works directly under the secretaries of their respective military departments, e.g. the secretary of the Army, the secretary of the Navy, and the secretary of the Air Force.

[6] U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) was a joint-service command of the United States Department of Defense. MACV was created on 8 February 1962, in response to the increase in United States military assistance to South Vietnam, and was first implemented to assist the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) Vietnam, controlling every advisory and assistance effort in Vietnam. It was reorganized on 15 May 1964 and absorbed MAAG Vietnam to its command when combat unit deployment became too large for advisory group control.

[7] Major John M. Newman (US Army, retired)spent 20 years with U.S. Army Intelligence, which included serving in in Thailand, the Philippines, Japan, and China. He eventually became executive assistant to the director of the National Security Agency (NSA). After leaving the NSA, Newman joined the University of Maryland where he taught courses in Soviet, Chinese Communist, East Asian, and Vietnam War history, as well as Sino-Soviet and U.S.-Soviet relations. Newman is the author of “JFK and Vietnam: Deception, Intrigue, and the Struggle for Power” (1992) and “Oswald and the CIA” (1995). He also served as an adviser to Oliver Stone while he was making “JFK” and was one of the experts called upon to advise the JFK Assassination Records Review Board.

[8] McGeorge “Mac” Bundy (March 30, 1919 – September 16, 1996) was an American academic who served as the U.S. National Security Advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 through 1966. He was president of the Ford Foundation from 1966 through 1979. Despite his career as a foreign-policy intellectual, educator, and philanthropist, he is best remembered as one of the chief architects of the United States’ involvement in Vietnam during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. After World War II, during which Bundy served as an intelligence officer, in 1949 he was selected for the Council on Foreign Relations. He worked with a study team on implementation of the Marshall Plan. He was appointed a professor of government at Harvard University, and in 1953 as its youngest dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, working to develop Harvard as a merit-based university. In 1961 he joined Kennedy’s administration. After serving at the Ford Foundation, in 1979 he returned to academia as professor of history at New York University, and later as scholar in residence at the Carnegie Corporation.

[9] In May 1963, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) directed a plan be prepared to support the RVN (Republic of Vietnam-same as South Vietnam) effort to carry out special operations in North Vietnam. On August 14th, 1963, the JCS approved the final plan that became Operation Plan (OPLAN) 34-63. Slight adjustments were again made and approved on September 9, 1963. Before fully implemented, a coup d’état against President Ngo Dinh Diem took place on November 2,1963. Despite the command confusion, commando raids continued under OPLAN 34-63. By December, 1963, MACV-SOG (Military Assistance Command Vietnam-Special Operations Group) became disappointed with performance and sought ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam-same as South Vietnamese Army) military participation. A new plan, known as OPLAN 34A was prepared that included ARVN with U. S. Navy support and was approved by JCS on December 15, 1963. Secretary of Defense McNamara and President Johnson wanted to deliver a strong message to North Vietnam that the U. S. would not accept the Communist invasion of South Vietnam. The main objective was to combine the attacks against the North with Diplomatic pressure to warn the North to cease their infiltration in Laos and South Vietnam. Thus, the United States entered into a new phase of the clandestine operations against the North.

[10] The term “Desoto Patrols” is derived from the first of this type of patrol carried out by the U.S. Navy, which took place off the coast of China in April, 1962. The first ship used was the destroyer USS DeHaven and the first patrol was just off the Chinese coast close to the Chinese “Tsingtao” naval base, hence “Desoto” stands for “DeHaven Special Operations off Tsingtao”. Inresponse to the Chinese announcement that they were now claiming a 12 mile territorial limit off their coast, the USS DeHaven carried out a mission in which it purposely would violate the 12 mile limit to demonstrate that the U.S. did not acknowledge it and to assert the U.S. right to navigate in what had been, before the Chinese claim, international waters. The DeHaven was equipped with special communications monitoring equipment so as to be able to intercept Chinese messages in response to its violation of the claimed Chinese territorial limit, thus allowing the US to get more accurate assessments of Chinese defensive capabilities.

[11] For the full story of the Gulf of Tonkin incident please go to the following blog post at fromanativeson.com https://fromanativeson.com/2015/05/24/deceit-in-high-places-the-real-story-of-the-gulf-of-tonkin-by-mark-arnold/