Note: I am pleased to present here the fifth and concluding installment of “Saying Goodbye to Hammerin’ Hank Aaron”; my tribute to my personal boyhood baseball hero, who passed away in January at the age of 86. When I started working on this series my intention was to write a simple eulogy based on what Hank meant to me as a young kid growing up in Seattle who loved baseball. Soon, however, as I studied more of Aaron’s life and accomplishments, I realized that would be impossible. As Jackie Robinson had before him, through his remarkable ability as a baseball player, Hank Aaron impacted not only the baseball record books, but our society as well, both profoundly and for the better. We are fortunate that he lived, and that he walked with us for the time he did. I hope you enjoy and learn from this farewell tribute to Hammerin’ Hank Aaron. His is a story that cannot be shared enough. This is for you, Hank!! MA

(To get the most out if this series the installments should be read in sequence. To make this easy I have linked Parts I through IV below)

___________________________________

his record-breaking 715th

On April 8th, 1974, at about 9 PM in the evening, exactly 47 years ago to the day as I write this, Hank Aaron knelt in the on-deck circle at Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium, waiting for his turn to hit. At that moment he was sitting on 714 career home runs, tied with the legendary Babe Ruth for the most in Major League annals. Over 53,000 fans, the most ever for a game at Atlanta’s home ballpark, were packed into the stadium, eager to witness history. A national audience of millions more were tuned in, watching on TV, most of them surely thinking that this could be the night that the most hallowed record in sports could be broken, and they were damned if they were going to miss it. The great Dodgers broadcaster, Vin Scully,[1] was on the call for his team’s radio network that night; while Milo Hamilton[2] handled the radio chores for the home team, and the veteran sportscaster Curt Gowdy [3]was on the NBC TV broadcast. It promised to be a night to remember, if only Hank could get hold of one.

For Henry Louis Aaron, getting to this point had been its own kind of odyssey. As a young Black ballplayer coming up in the years immediately following the 1947 breakthrough of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey,[4] there was still much in the way of racial injustice and prejudice to overcome, not only in the game, but in the society the game reflected. In the deep South of those days, where Hank was born and raised, Jim Crow still held sway, as he well knew. He had tackled it head on when he and two teammates, Felix Mantilla and Horace Garner,[5] became the first Blacks to integrate the Sally League[6]when they played for the Jacksonville Braves in 1953, six years after Jackie had broken the Major League color barrier. As Robinson had before them, Hank and his friends had to endure the bitter racist taunts and slurs, the hate-filled stares; the threats of violence and sudden death. Through it all they kept to the code. As Branch Rickey had demanded of Jackie Robinson, they could not respond in kind; they could not strike or lash back; for there was a larger purpose at stake; one that demanded a higher mind-set and example to succeed. Following Robinson’s standard, Hank and his teammates gracefully accomplished for the Southern Minor Leagues what Robinson had done for the Majors six years earlier: integration.

Once Aaron made it to the Major Leagues with the Milwaukee Braves in 1954, it didn’t take him long to establish himself as an elite player. By 1955 he was an All-Star, the first of what would be 21 consecutive seasons and 25 appearances in the mid-summer classic.[7] By 1957, with Hank leading the National League in home runs, RBIs, runs scored and total bases, he paced the Braves to the NL pennant and a World Series victory over the Yankees; in acknowledgement earning the National League MVP award. From that point on through the next 16 seasons he set a standard for excellence and consistency rarely paralleled in big time sports, averaging 38 homers and 109 RBIs per season while hitting .311. Never a one-dimensional player, Aaron could also steal a base, garnering 240 in his career, while winning 3 Gold Glove awards for his play in right field. Whoever originally coined the term “5-tool player” must have been thinking of Aaron as they did so.

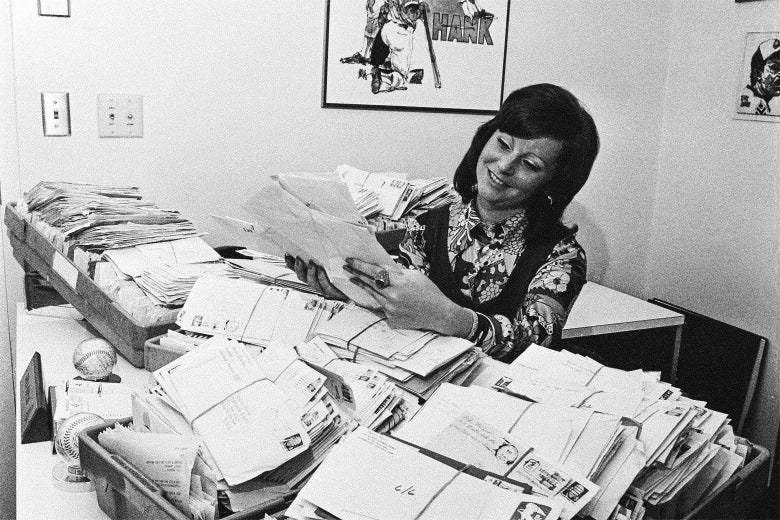

For all that accomplishment, it’s what Hank did in breaking Ruth’s record that has permanently etched him in the minds of fans and the annals of greatness, and not just for baseball. I’ve often thought how dismaying it must have been for him, as he closed in on the record, to have to experience and endure again the same bigotry, but on a MUCH larger scale, that he had challenged 20 years earlier when he, Mantilla and Garner integrated the Sally League. At the outset of the 1973 season Hank stood at 673 career dingers, exactly 41 short of tying Ruth. Across that summer, as he steadily approached the 714 benchmark, the letters and messages to him mounted to unprecedented heights, as many as 3,000 per day and over 900,000 in total, more than anyone in a non-political job in the country. While many of these letters contained words of appreciation and encouragement, an astonishing percentage were born of the heart of darkness, laced with racist comments and epithets; even death threats:

“Dear Nigger Henry,

You are (not) going to break this record established by the great Babe Ruth if

I can help it. … Whites are far more superior than jungle bunnies… My gun

is watching your every black move.”

“Dear Henry Aaron,

How about some sickle cell anemia, Hank?”

“Dear Hank Aaron,Retire or die!!! The Atlanta Braves will be moving around the country, and I’ll be moving with them. You’ll be in Montreal June 5-7. Will you die there? You’ll be in Shea Stadium July 6-8…You’ll die in one of those games. I’ll shoot you in one of them…”

The sheer volume of mail necessitated hiring a full-time secretary to handle, and the racist comments and threats required retaining body guards and special accommodations, even the FBI, to protect Hank. Many years later, in a statement he made to the NY Times in 1990, he describes the effect on himself and his family:

“My kids had to live like they were in prison because of kidnap threats, and I had to live like a pig in a slaughter camp. I had to duck. I had to go out the back door of the ballparks. I had to have a police escort with me all the time. I was getting threatening letters every single day. All of these things have put a bad taste in my mouth, and it won’t go away. They carved a piece of my heart away.”

Despite the threats and distractions, Hank hit 40 home runs in that ’73 season, finishing the campaign with 713, one short of Ruth. You might think that the off season would provide a needed respite from the mail and attention for Hank, but if you did you’d be wrong. The racist letters and threats continued all winter and on into 1974’s spring training, and there was endless speculation by sports writers and broadcasters as to when Hank would tie or break the record. Once the season started it didn’t take long to find out. In the first game of the 1974 season, against the Reds in Cincinnati, in his first at bat of the season, Hank launched his record tying 714th home run off Reds starter Jack Billingham[8], over the left field wall 375 feet away. Instead of that dinger being purely a cause for celebration, however, another controversy was ignited.

Reds pitcher Jack Billingham

Before the season opening series vs. the Reds, Braves manager and Hank’s former teammate Eddie Mathews[9], wanting to ensure that Aaron would break the record in front of hometown fans in Atlanta, had planned to hold him out of the first 3 games in Cincinnati. On getting wind of that news, MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn [10]contacted Mathews and told him that he wanted Hank to play in at least 2 of the 3 games. When Aaron got the record-tying shot in his first at bat, however, in defiance of the Commissioner Eddie reverted to his original plan and sat the future home run king in the second game of the series. On learning of Mathews’ resistance, Kuhn called him on the phone and told him that if Hank wasn’t on the field for the 3rd game of the series he and the Braves would receive “serious penalties.” Mathews yielded and Aaron was in the line-up for the 3rd game, though he played poorly, striking out twice and committing an error.

That should have been the end of any “controversy”, but Kuhn compounded things when he didn’t show up in Atlanta for the Braves home opener a few days later against the LA Dodgers, sending instead former Negro League star and Hall of Famer, Monte Irvin,[11] to represent him. That the Commissioner of Major League Baseball could be so small minded as to carry whatever his problem was with Hank playing or not playing over to the Dodgers series, was baffling to many fans, and remains so to this day. At the time Kuhn stated that he had a prior obligation in Cleveland—a meeting with a Cleveland Indians booster club.

Really? A Cleveland Indians booster club? If that doesn’t ring true for you, you are not alone. Kuhn’s absence prompted the Braves travelling secretary at the time, Donald Davidson, to comment:

“Who’s hitting No. 715 in Cleveland? He couldn’t’ find time to honor Hank Aaron and he won’t be here tomorrow, either. … With apologies to Cleveland, I don’t know of any dinner that could be big enough to keep him there instead of here.”

Hank a trophy after his 714th homer

Making Kuhn’s absence even more peculiar was the fact that he WAS in Cincinnati for Aaron’s 714th. When it happened, he ordered the game paused for an on-field field ceremony at which he and then Vice President Gerald Ford [12]presented Hank with a trophy acknowledging the historic long ball. My own theory is that when Eddie Mathews didn’t play Hank in the 2nd game against the Reds, it pissed Bowie off and called to mind an earlier upset that occurred when Hank hit his 700th dinger in the 1973 season. On that occasion Aaron received over 100 acknowledgements and messages from dignitaries and important people all over the country acknowledging him. Notably absent, however, was a message from the MLB Commissioner, which prompted Hank to comment:

“I would think that the commissioner would send one (a message), too. I felt let down. I think what I did was good for baseball. … Regardless of how small he thinks it is hitting that home run, it wasn’t small to me. I feel he should have acknowledged it somehow. Frankly, it bothers me.”

Kuhn’s lame response to Hank at the time was that if he started acknowledging player accomplishments he would run the risk of upsetting someone through omission. According to Aaron, about the Commissioner’s failure to acknowledge the 700th, Kuhn told him that, “…if he started sending telegrams, he’d end up sending telegrams every time someone got three doubles.”

Based on all this, I think it plausible (just my theory) that Hank’s critical comment in the wake of his 700th homer upset Kuhn, and that Mathews’ counter-intention, albeit months later, exacerbated things. Feeling slighted, Kuhn chose the incredibly small-minded response of not attending the Braves home opener. When Hank then hit the historic record-breaking shot in that game, the PR flap was on, leaving poor Monte Irvin, who agreed that Kuhn should have been there, to pick up the debris. Of course, all that noise is incidental to the fact that Hank Aaron walked into history when he blasted his 715th. The magnificence of that moment made any concern about the Commissioner’s presence or absence shrink to insignificance.

would he situate the helmet on his head

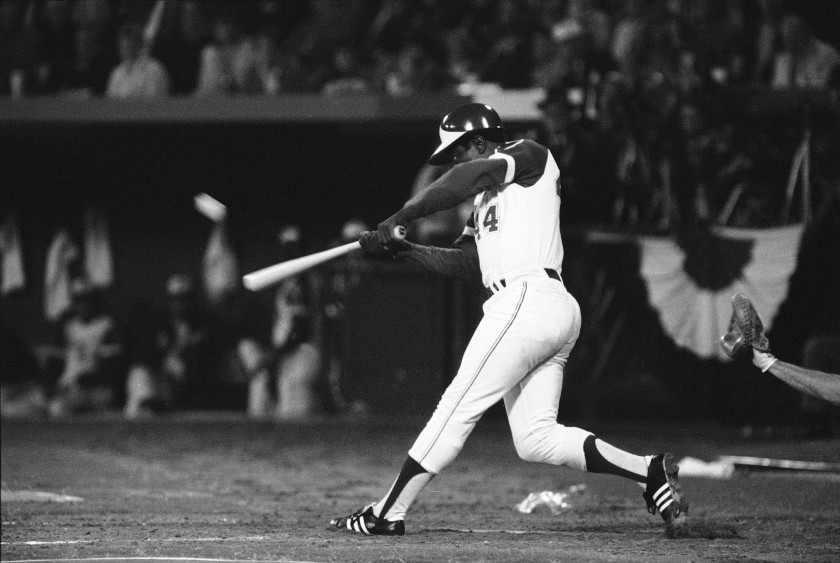

And so, on this April 8th, in the 21st season of Hank’s career, all that earlier experience was now coalescing into this one historic at bat. When Darrell Evans,[13] the hitter in front of Aaron, reached first on an error, Hank got up from one knee and strode casually from the on-deck circle to the batter’s box, carrying his batting helmet in his hand. That was Hank’s way for as long as I had followed him. Once he got to the batter’s box, only then would he situate the helmet on his head, while the catcher, the umpire and the pitcher all waited. It was as if Hank was saying to them, “This is my world, and you all are just visitors here.” Indeed, if those were Hank’s thoughts as he dug into the batter’s box and got ready to face Dodgers pitcher Al Downing,[14] there was much truth in them.

Meanwhile, 60 feet and 6 inches away, Downing was getting ready to deliver his first pitch to the already legendary Braves slugger. With the game in the 4th inning, and nursing a 3-1 lead, he was on his 2nd time through the Braves lineup, having walked Aaron on 5 pitches his first time up. The Dodger pitcher had even helped his own cause with a run-scoring single in the 3rd inning. With Darrell Evans now on first, however, Hank was the game-tying run at the plate. Downing would have to be careful with the Atlanta slugger. His first pitch reflected this, coming in low and in the dirt, eliciting boos from the crowd. They didn’t want to see another walk. As for the next pitch, some say it was a mislocated fast ball, while others say it was a hanging slider. Whatever it was, for a fleeting moment it seemed to suspend tantalizingly, about thigh high in the middle of the plate as Hank launched his exquisitely timed swing, followed a millisecond later by the sound of his bat making square contact with the ball.

It took a moment for Vin Scully, Milo Hamilton and Curt Gowdy, the broadcasters calling the game, to register what they were seeing; but once they did they each called the moment superbly. For this writing I am using Scully’s description, as I think of the three it does the best at reporting the moment and capturing its cultural significance. Here is his call as he delivered it:

“Once again, a standing ovation for Henry Aaron. So, the confrontation for the 2nd time, and he walked in the 2nd inning. He means the tying run at the plate now, so we’ll see what Downing does…Al at the belt, delivers, and he’s low…ball one. And that just adds to the pressure…the crowd booing, Downing has to ignore the sound effects…and stay a professional and pitch his game…One ball and no strikes, Aaron waiting, the outfield deep and straight away…Fastball…THERE’S A HIGH DRIVE INTO DEEP LEFT-CENTER FIELD, BUCKNER[15] GOES BACK, TO THE FENCE…IT IS GONE!!!”

At this point in the broadcast Scully goes quiet as he takes in the whole moment. As for Hank, when asked what he was thinking as he circled the bases after his record- breaking blast, he responded that he was glad that his parents could be there to see it, and that he just wanted to make sure he touched all the bases. There was an anxious moment, however, as Hank rounded 2nd base, when two young, white teenagers[16] who had left the stands and run onto the field, made contact with him as he advanced toward 3rd base. Unbeknownst to the two kids, one of Aaron’s bodyguards, a police officer named Calvin Wardlaw, was watching them approach Hank, his .38 at the ready should the two exhibit any bad intent. Wardlaw’s restraint was rewarded and disaster averted when the two kids, who for their trespass would end up spending the night in jail, merely gave Aaron congratulatory pats on the back. As Hank rounded third and approached the growing throng waiting to greet him at home plate, the realization fully hit home to all those watching and listening—the All-Time home run record, which had stood for 39 years and which many thought would last forever—had at last been broken.

A couple of seconds after Hank crossed home plate and was being mobbed by the players and reporters, Scully picks up with his call:

“What a marvelous moment for baseball,” the famous broadcaster intoned. “What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia; what a marvelous moment for the country and the world…A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol, and it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron, who was met at home plate, not only by every member of the Braves, but by his father and mother. He threw his arms around his father, and as he left the home plate area his mother came running across the grass, threw her arms around his neck, (and) kissed him for all she was worth.

The Dodgers broadcaster then continued:

“As Aaron circled the bases the Dodgers on the infield shook his hand, and that was a memorable moment. Aaron is being mobbed by photographers, he is holding his right hand high in the air, and for the first time in a long time, that poker face of Aaron’s shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months.

And then Scully summed up:

“It is over! At 10 minutes after 9, in Atlanta, Georgia, Henry Aaron has eclipsed the mark set by Babe Ruth…”

Ever a man of few words, Hank was always one to let his actions do his talking. Thus, in the hectic moments after his 715th, when handed a microphone and asked for his thoughts on his history making accomplishment, he uttered just one sentence:

“I just thank God it’s all over with,” he said.

Epilog

Aaron would finish that 1974 season with 20 homers, a .269 batting average and 68 RBIs while playing in 112 games. At the time he was 40 years old. After the season was over he was traded by the Braves to the Milwaukee Brewers in the American League, and would finish his career in the town where it started two decades earlier. When Hank walked away from the game following the 1976 season he did so with a career .305 batting average and more home runs (755), RBIs (2,297) and total bases (6,856) than any player who ever lived. His 3,771 hits were second only to Ty Cobb, and currently rank 3rd behind only Cobb and the all-time hit leader Pete Rose. [17]Capping his illustrious career in 1982 was his induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame, after being elected on the first ballot with nearly 98% of the votes. In the entire history of MLB to that point, only Ty Cobb had been elected with a higher percentage.

In 2007, 33 years after Hank surpassed the Babe, Barry Bonds [18]of the San Francisco Giants became the career home run leader when he hit his 756th long ball at Pac-Bell ballpark in San Francisco. By the time he retired after the 2007 season Bonds had amassed 762 home runs in his career, thus establishing the record he still holds. Tainting Bonds’ accomplishment, however, is his near certain use of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs), which to this point has surely cost him election to the Hall of Fame. Despite the PED shadow over Bonds, on the occasion of his 756th Aaron graciously acknowledged him with a video presentation that played on the Jumbo-Tron screen during the on-field ceremony after Barry’s blast. In his video comments acknowledging Bonds, as he always did, Hank took the high road:

“I would like to offer my congratulations to Barry Bonds on becoming baseball’s career home run leader. It is a great accomplishment that required skill, longevity, and determination. Throughout the past century, the home run has held a special place in baseball and I have been privileged to hold this record for 33 of those years. I move over now and offer my best wishes to Barry and his family on this historical achievement. My hope today, as it was on that April evening in 1974, is that the achievement of this record will inspire others to chase their own dreams.”

In summing up Hank Aaron’s career, the process of researching and writing this piece has broadened my perspective greatly. There are only a handful of Major League ballplayers, if that many, whose positive impact on the game is matched or exceeded by their positive impact on our society itself. Jackie Robinson is one, of course; and though I didn’t realize it fully when I started writing this tribute, Hank Aaron is another. Researching this piece has been a revelation for me. As a kid and on through my teen years I was such an Aaron fan, and I so admired what he did throughout his career; his consistency as a batsman, and in ultimately becoming the greatest home run hitter ever. His accomplishments on the field were an inspiration to me. If that was all he did, he would be long-remembered and honored by many as the great Hall of Fame ballplayer he was.

But, there was a far greater dimension to him than I realized in my youth, one which I have now come to fully appreciate. That greater dimension consists of the grace, restraint and tolerance he displayed in facing and overcoming circumstances and barriers he never should have had to deal with in order to play this simple game. No white player ever faced such barriers, but you never would have known it by the way Hank went about his business and played the game. Like mirrors, people like Jackie and Hank reflect our misdeeds, omissions and prejudices back at us. In so doing they afford us an opportunity for the self-reflection necessary to amend and change our ways, in the process confronting who we really are, which I believe is basically good. That is how such people improve society, one person at a time, and that is exactly what Hank Aaron did.

He was such a magnificent baseball player, but he was an even better human being; and though we will miss him, his example will last forever.

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2021

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Vincent Edward Scully (born November 29, 1927)is a retired American sportscaster. He is best known for his 67 seasons calling games for Major League Baseball’s Los Angeles Dodgers, beginning in 1950 (when the franchise was located in Brooklyn) and ending in 2016. His run constitutes the longest tenure of any broadcaster with a single team in professional sports history, and he is second only to Tommy Lasorda (by two years) in terms of number of years associated with the Dodgers organization in any capacity. He retired at age 88 in 2016, ending his record-breaking run as their play-by-play announcer.

[2] Leland Milo Hamilton (September 2, 1927 – September 17, 2015) was an American sportscaster, best known for calling play-by-play for seven different Major League Baseball teams since 1953, including the Atlanta Braves from 1966 to 1975. He received the Ford C. Frick Award from the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1992.He was known by his middle name, which is pronounced “MY-loh”.

[3] Curtis Edward Gowdy (July 31, 1919 – February 20, 2006) was one of the great American sportscasters in the second half of the 20th century. He called Boston Red Sox games on radio and TV for 15 years, and then covered many nationally televised sporting events, primarily for NBC Sports and ABC Sports in the 1960s and 1970s. As an aside, my mother and Gowdy were schoolmates, attending the same high school in Wyoming, where Gowdy was born and raised.

[4] The story of Branch Rickey’s collaboration with Jackie Robinson in breaking the Major League Baseball color barrier is well covered in Part III of this series, which is linked here:

[5] For the story of Hank Aaron, Felix Mantilla and Horace Garner integrating the deep South Minor Leagues please see Part III of this series, linked here: http://fromanativeson.com/2021/03/14/5234/

[6] The acronym SAL, which stands for “South Atlantic League” is colloquially known as the “Sally” League. The “Sally” League is a Minor League comprised of teams in the deep South.

[7] Though Hank Aaron was an All-Star for 21 seasons, due to there having been two All-Star games each summer between 1959 and 1962, he made 25 All-Star game appearances.

[8] John (Jack) Eugene Billingham (born February 21, 1943) is an American former professional baseball player and coach. A very good pitcher (145 career victories) he played in Major League Baseball as a right-handed pitcher from 1968 through 1980, most notably as a member of the Cincinnati Reds dynasty that won three National League pennants and two World Series championships between 1972 and 1977.

[9] Edwin (Eddie) Lee Mathews (October 13, 1931 – February 18, 2001) was an American Major League Baseball (MLB) third baseman. He played 17 seasons for the Boston, Milwaukee and Atlanta Braves (1952–1966); Houston Astros (1967) and Detroit Tigers (1967–68). Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1978, he is the only player to have represented the Braves in the three American cities they have called home. Considered one of the greatest third basemen of all time and a feared power hitter (512 career home runs). he played 1,944 games for the Braves during their 13-season tenure in Milwaukee—the prime of Mathews’ career. Mathews and Hank Aaron were teammates on the Braves from Hanks rookie 1954 season until Mathews was traded in 1966.

[10] Bowie Kent Kuhn (October 28, 1926 – March 15, 2007) was an American lawyer and sports administrator who served as the fifth Commissioner of Major League Baseball from February 4, 1969 to September 30, 1984. He served as legal counsel for Major League Baseball owners for almost 20 years prior to his election as commissioner. Kuhn was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008.

[11] Monford Merrill “Monte” Irvin (February 25, 1919 – January 11, 2016) was an American left fielder and right fielder in the Negro leagues and Major League Baseball (MLB) who played with the Newark Eagles (1938–1942, 1946–1948), New York Giants (1949–1955) and Chicago Cubs (1956). His career was interrupted by military service from 1943 to 1945. When he joined the New York Giants, Irvin became one of the earliest African-American MLB players. He played in two World Series for the Giants. When future Hall of Famer Willie Mays joined the Giants in 1951, Irvin was asked to mentor him. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973. After his playing career, Irvin was a baseball scout and held an administrative role with the MLB commissioner’s office.

[12] Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. (born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913 – December 26, 2006) was an American politician and attorney who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. A member of the Republican Party, Ford previously served as the 40th vice president of the United States from 1973 to 1974. He assumed the presidency after Richard Nixon resigned because of the Watergate scandal. To date, Ford is the only person to have served as both vice president and president without being elected to either office by the Electoral College.

[13] Darrell Wayne Evans (born May 26, 1947) is a former American baseball player, coach and manager. He played 21 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB), beginning his career as a third baseman with the Atlanta Braves (1969–1976, 1989), alternating between first and third base with the San Francisco Giants (1976–1983), and playing much of his later career as a first baseman and then a designated hitter for the Detroit Tigers (1984–1988). He won a World Series championship with the Tigers in 1984. Evans had most of his success in the early and late stages of his career. He was a two-time All-Star, first with the Braves in 1973 and then with the Giants in 1983. In 1973 he helped the Braves become the third team in MLB history to have 3 players hit 40 or more homers. (Evans 41, Davey Johnson 43 and Aaron 40)

[14] Alphonso Erwin Downing (born June 28, 1941) is an American former professional baseball pitcher. He played in Major League Baseball for the New York Yankees, Oakland Athletics, Milwaukee Brewers, and Los Angeles Dodgers from 1961 through 1977. Downing was an All Star in 1967 and the National League’s Comeback Player of the Year in 1971. Despite allowing Hank Aaron’s record breaking 715th home run, Downing was a very good MLB pitcher, winning 123 games in his career. He led the American League in strikeouts in 1964 and had an excellent career ERA of 3.22.

[15] William Joseph Buckner (December 14, 1949 – May 27, 2019) was an American professional baseball first baseman and left fielder, who played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for five teams from 1969 through 1990 including the Chicago Cubs, the Los Angeles Dodgers, and Boston Red Sox. Beginning his career as an outfielder with the Dodgers, he helped the team to the 1974 pennant with a .314 batting average. Buckner had an excellent Major League career across 21 seasons. He had a career batting average of .289 with 174 homers and 1208 RBIs. Ironically he is most remembered for his historic error in the 1986 World Series when he let a Mookie Wilson ground ball go between his legs which allowed the Mets to come back and win Game 6. The Mets then won game 7 to win the Series 4 games to 3.

[16] The two teenagers, both 17 years of age at the time and seniors in high school, who ran onto the field to congratulate Aaron on his 715th were named Britt Gaston and Cliff Courtenay.

[17] Peter Edward Rose Sr. (born April 14, 1941), also known by his nickname “Charlie Hustle“, is an American former professional baseball player and manager. Rose played in Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1963 to 1986, and managed the Cincinnati Reds from 1984 to 1989. Rose was a switch hitter and is the all-time MLB leader in hits (4,256), games played (3,562), at-bats (14,053), singles (3,215), and outs (10,328).[1] He won three World Series, three batting titles, one Most Valuable Player Award, two Gold Gloves, and the Rookie of the Year Award, and also made 17 All-Star appearances at an unequaled five positions (second baseman, left fielder, right fielder, third baseman, and first baseman). Rose won both of his Gold Gloves when he was an outfielder, in 1969 and 1970. In August 1989 (his last year as a manager and three years after retiring as a player), Rose was penalized with permanent ineligibility from baseball amidst accusations that he gambled on baseball games while he played for and managed the Reds; the charges of wrongdoing included claims that he bet on his own team. In 1991, the Baseball Hall of Fame formally voted to ban those on the “permanently ineligible” list from induction, after previously excluding such players by informal agreement among voters. After years of public denial, Rose admitted in 2004 that he bet on baseball and on the Reds. The issue of Rose’s possible reinstatement and election to the Hall of Fame remains contentious throughout baseball.

[18] Barry Lamar Bonds (born July 24, 1964) is an American former professional baseball left fielder who played 22 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) with the Pittsburgh Pirates and San Francisco Giants. He received a record seven NL MVP awards, eight Gold Glove awards, a record 12 Silver Slugger awards, and 14 All-Star selections. He is considered one of the greatest baseball players of all time. Bonds holds many MLB hitting records, including most career home runs (762), most home runs in a single season (73, set in 2001) and most career walks.He led MLB in on-base plus slugging (OPS) six times, and placed within the top five hitters in 12 of his 17 qualifying seasons. Bonds, a superb all-around baseball player, won eight Gold Glove awards for his defensive play in the outfield. He stole 514 bases with his base running speed, becoming the first and only MLB player to date with at least 500 home runs and 500 stolen bases (no other player has even 400 of each). He is ranked second in career Wins Above Replacement among all major league position players by both Fangraphs and Baseball-Reference.com behind only Babe Ruth. However, Bonds led a controversial career, notably as a central figure in baseball’s steroids scandal. In 2007, he was indicted on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice for allegedly lying to the grand jury during the federal government’s investigation. The perjury charges against Bonds were dropped and an initial obstruction of justice conviction was overturned in 2015.Bonds became eligible for the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 2013, yet he has not received the 75% of the vote needed to be elected, with his highest share of the vote coming in 2021 balloting, his ninth of ten years of eligibility, when he received 61.8%. Some voters of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) have stated that they did not vote for Bonds because they believe he used performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs)