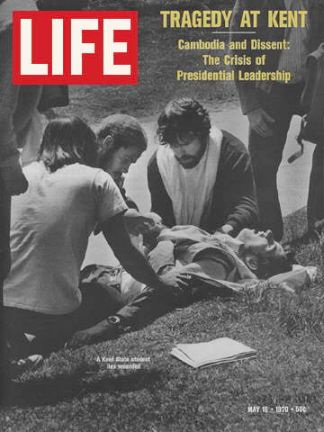

the students shot at Kent State

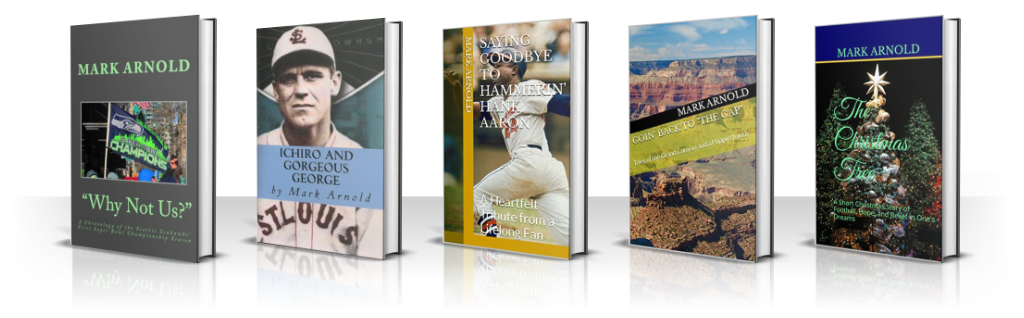

Note: Presented here is the third installment of “Hangin’ With the New Left,” an account of my personal observations and involvement in the anti-Vietnam War and Black Student Union protests on the University of Washington campus in the early 1970s. As this installment builds upon the information presented in Parts I and II, for the sake of understanding it would be best to read them in sequence. To facilitate this, both prior installments are linked below this introduction. Part III deals with the events of the spring of 1970, from the indictments handed down on the “Seattle 8” to the protests surrounding President Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia and the National Guard killings of 4 students at Kent State University. As I have watched the current situation develop with the Black Lives Matter protests in our country, and radical efforts to de-fund the police; and even to take over a section of our city (Seattle) as an autonomous zone, I have been increasingly struck by the similarities between the protests of my youth 50 years ago and what is happening now; especially the influence of Marxist and “New Left” principles on what otherwise would be a purely Civil Rights movement and, 50 years ago, the anti-Vietnam War movement. These influences are not new. The perspective of history is, I believe, necessary to our understanding of the present; thus, knowing it is very important. In this series, and in particular this installment, you have my effort to chronicle some of this history as I personally experienced and witnessed it; and to share some of the insights I’ve gained since. I hope you enjoy it and learn from it. MA

_______________________________

Surprisingly, the beginning of the 1970 spring quarter on the UW campus was relatively calm. I’d expected the Black Student Union protests to pick up where they left off at the end of the winter quarter, but, for whatever reason, nothing much was happening. Things would stay that way for most of April. I spent the time acclimating to my new classes and playing as much basketball at the Intramural Activities Building as I could. With the end of the winter quarter my time in Michael Lerner’s philosophy class was over; meaning I was no longer getting my daily dose of New Left ideology. As I found his manner somewhat overbearing, I didn’t much miss Lerner as a professor; nevertheless, the radical ideas he presented in his class did affect me. I no longer looked at our country and the world in the same way. I had begun to seriously question what I was now seeing as systemic racism, as well as our involvement in the Vietnam War; much to the angst of my father, with whom I was now frequently arguing.

Looking at this change in me from my dad’s perspective, he must have thought I’d lost my mind. I’d always more or less accepted his political views, which could be expressed as deeply patriotic; a belief in the rightness of the United States in its battle against communism around the world. Also, as far as racism was concerned, it just never seemed to be an issue for him. It was not something we ever had to deal with in our daily lives, and it wasn’t something that he perceived as a significant problem in our nation. My eyes, however, were being opened on both counts; and I wasn’t shy about expressing these new views to him. Our conflicts became the source of considerable upset in our family, especially for my mother. Both headstrong, neither of us would back down, much to the detriment of our family peace; a fact I today deeply regret.

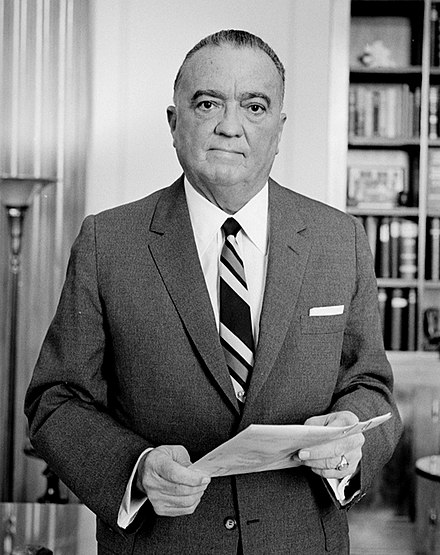

As calm as the campus appeared in that early spring of 1970, behind the scenes U.S. government legal cogs were turning. Unbeknownst to any of us in Seattle, and especially the Seattle Liberation Front (SLF) leadership, when the Federal Courthouse protest occurred in February it caught the attention of the Justice Department in Washington DC, specifically U.S. Assistant Attorney General Will Wilson, who then sent a message to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover [1]ordering him to launch an investigation of the SLF. He didn’t have to tell Hoover twice—with an eye toward destroying the SLF, the FBI Director had been investigating the Seattle radical group practically from the day it started. Wilson also informed Hoover in his memo that very soon a Justice Department official, Special Litigation Chief Guy Goodwin, would be sent to Seattle to establish a grand jury, the purpose of which would be to hear testimony from subpoenaed witnesses and issue indictments against the SLF TDA protest organizers. The government’s plan was to use the same Federal conspiracy laws that were used in the infamous Chicago 7 Conspiracy[2] trial to take out the SLF leadership, thereby destroying the group. It would be up to Hoover’s investigation to develop enough in the way of witnesses and evidence to justify the indictments.

The FBI’s investigation encountered a significant problem from the start, however. Hoover had informed the Seattle FBI office that the SLF was in fact dominated by the Seattle faction of “Weatherman”, the violent, radical group that had splintered from SDS[3] earlier in 1969. In painting the SLF with a “Weatherman” brush the FBI Director was spreading false information, and he knew it. Initially, Bureau investigators in Seattle were having difficulty discovering anything to indicate that Michael Lerner, Chip Marshall and the rest of the SLF leadership had broken any laws at all. None of them had been arrested or charged with any crimes at the protest itself, and finding evidence indicating violation of conspiracy laws was proving very difficult; so much so that on 24 February, a week after the TDA riot, government investigators reported in a memo that their findings thus far had “failed to indicate a violation of Federal Antiriot Laws.” Three days later, on 27 February, the U.S. attorney for Western Washington, Stan Pitkin, sent a message to the FBI stating that due to insufficient evidence he, “could not render a prosecutive opinion in this matter at this time.”

These were the “glory” days of Hoover’s COINTELPRO [4]strategy, however, and by 1970 the Bureau was well-versed in its tactics; one of which was the use of controlled media outlets to spread black propaganda against those targets the FBI Director had deemed to be security threats. That is the most likely explanation for a couple of articles that appeared in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on April 5th and April 6th, both of which had the obvious intention of discrediting the SLF. Headlined, “SLF: Seattle Is the Target of Revolutionaries,” the first article stated that Seattle and the University of Washington had become “the primary target of an experienced band of hard-core revolutionaries,” which is how the article characterized the SLF leaders. The article went on to say that the SLF radicals had come to Seattle because they considered the city ripe for revolution; and that the SLF “holds in contempt many aspects of American society. It aims to rally under one revolutionary banner every possible dissident group and individual.” The second article then built on the tone of the first. Taking its cue from FBI Chief Hoover’s mis-characterization of the SLF as a creature of “Weatherman”, the article described the SLF as a “rebirth…an ‘enfant terrible’“ of SDS and Weatherman.

Fifty years later it’s hard to gauge the effect the articles had, except to say that with Seattle’s 1970 middle class the SLF never won any popularity contests. It’s also hard to estimate the full extent of COINTELPRO operations against the SLF; but it is certain it didn’t stop, or start, with the newspaper articles. The government completely controlled the grand jury process, the selection of witnesses and the issuing of subpoenas; and could, therefore, steer the testimony and evidence as they wished; the best example of which was their star witness, an FBI plant and “agent provocateur”[5] named Horace Parker. Much of the government’s developing case against the Seattle radicals would hinge on Parker’s testimony. Later that year, during the trial of the “Seattle 8”, as the defendants would come to be called, Parker acknowledged under examination and cross-examination that, while under FBI employ, he infiltrated the SLF; reported on its activities to his FBI handlers once and sometimes twice a day; encouraged other SLF members to commit violent acts; helped train SLF members in firearms and target shooting; offered other SLF members access to explosive devices; provided the paint used to splatter the Federal Courthouse at the TDA riot; and was involved in illegal drug use. He also acknowledged while under oath that he would be willing to go to “any length,” including breaking the law and lying, to “get” the SLF radicals.

conspiracy to violate Federal Anti-riot Laws

With Parker’s “eye-witness” evidence and testimony in hand, on April 16th, 1970, the U.S. government at last moved legally and issued indictments against eight SLF leaders, charging them with conspiracy to violate Federal Anti-riot laws[6] for their roles in staging the February 17th TDA Federal Courthouse protest. The eight, in addition to my philosophy professor Michael Lerner, included Chip Marshall, Jeff Dowd, Susan Stern, Joe Kelly, Michael Abeles, Roger Lippman, and Michael Justesen. When they were issued, the indictments were the biggest news in New Left circles on campus and in the city. The “Seattle 8” would go on to become nationally famous, as the “Chicago 7”, in support of whom the February TDA protest was held in the first place, had before them.

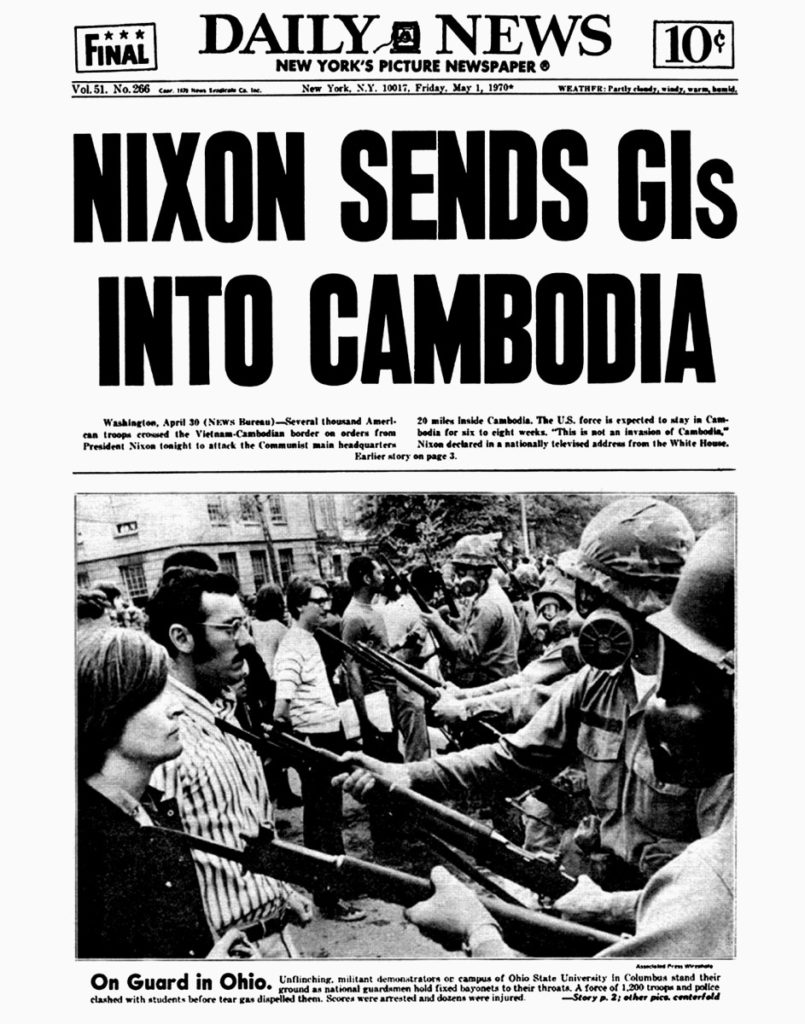

Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia

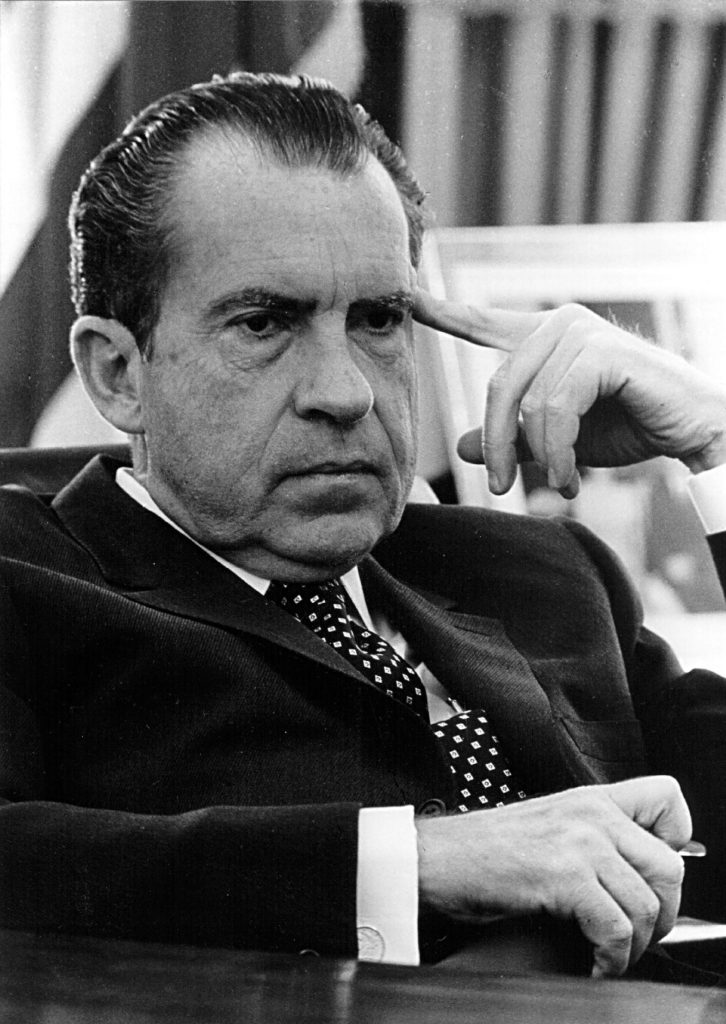

While all this was going down in Seattle, President Richard Nixon was engaged in final planning for what would be a major escalation of the Vietnam War. In April of 1970 Nixon had been in office for just over a year. Running as a “law and order” candidate and as a champion of what he called the “silent majority,” he won the popular vote in the 1968 presidential election over vice president Hubert Humphrey by about one percent; a very narrow margin. Taking advantage of the third-party candidacy of former Alabama governor George Wallace[7], who took five states and over 40 electoral votes in the traditionally democratic south, Nixon won the electoral college vote by a wider margin. Since he was a Republican, and as Democrats had been in the White House for the prior eight years (JFK: 1961-1963 and LBJ: 1963-1969), years that saw the most major escalation of the war and the rise of the anti-war movement, Nixon succeeded in separating himself in voter’s minds from those he claimed were responsible for the war; something that was patently untrue. In fact the U.S. had been deeply involved in Vietnam since 1954 and less directly involved since 1946. From 1953-1961 Nixon was vice president in the administration of president Dwight Eisenhower, and in that role had participated in many of the decisions that resulted in the U.S. becoming directly involved in Vietnam in the first place. The truth was “Tricky Dick” was as responsible for our nation’s Vietnam nightmare as anyone, except perhaps LBJ.

The above gives you some slight insight into the man, Richard Nixon, who on April 28th, 1970, ordered U.S. GIs to invade South Vietnam’s neighboring country, Cambodia. Ostensibly the purpose of the invasion was to destroy bases just across the Cambodian border, at the southern end of the Ho Chi Minh Trail,[8] used by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces as staging areas for their attacks into South Vietnam. It wasn’t until two days later, however, on April 30th, that Nixon finally announced to the American people what he’d done. The response on college campuses and within the anti-war movement was nearly instantaneous. The news expanded already planned May Day anti-war protests across the nation, and within a couple of days roughly four million students across over 400 college campuses around the country ignited in dissent; among them the University of Washington. Nothing I’d experienced in my short protest career to that point, not the TDA riot a couple months earlier, nor the Black Student Union protests, could have prepared me for what we would witness and experience across the next several weeks.

On, Friday, May 1st, 1970, students and demonstrators in cities all over the country, inflamed by the U.S. Cambodia incursion, held the scheduled May Day anti-war protests with a fervor reinvigorated by what they perceived as Nixon’s betrayal. It had been barely a year since his inaugural address, when we heard him promising to end the war; and instead we now had Cambodia. In Seattle, over one thousand upset but otherwise peaceful protesters gathered in front of the Federal Courthouse in downtown (the same courthouse made famous by the SLF-TDA riot in February) and heard speaker after speaker decry Nixon’s latest expansion of the war. Not so much in Seattle, but on many other campuses across the nation, the protests continued into and through the weekend. Students at Princeton University came up with the idea of a national student strike, and by Sunday, May 3rd, that idea had coalesced into an actual strategy, agreed upon by student activists from eleven different schools in a meeting at Columbia University. From there the idea spread like wildfire to universities all over the country. The student strike was scheduled to begin on Monday, May 4th and would continue through Friday, May 8th. The plan had scarcely been implemented, however, when everything suddenly, violently and permanently, changed.

Kent State students

One of the many schools involved in anti-war protests that weekend was Kent State University. Located in northeast Ohio, Kent State, by the time of the Cambodia invasion, had already become a focal point of student anti-war dissent, which Cambodia exacerbated. The weekend of Friday, May 1st, through Sunday, May 3rd, saw student protests on campus each day and on into the evening, with some property damage resulting from rioting during which rocks and bottles were thrown. With another protest scheduled to take place on Monday, May 4th, the mayor of the city of Kent, a man named Leroy Satrom, along with the governor of Ohio, James Rhodes, had seen enough. That Sunday, at Satrom’s request, governor Rhodes declared the situation at Kent State to be a state of emergency, which allowed him to mobilize the Ohio National Guard. Arriving on campus that evening, the Guard was immediately faced with groups of protesting students and, using tear gas, was able to disperse them without much damage.

The next day’s demonstration was slated to be held on the university Commons at noon, and by the time the protesters started arriving the Guard was already in place. As the morning advanced toward noon the crowd grew, to the point where at least 1,000 student demonstrators were gathered in the Commons; by some estimates as many as 2,000. The soldiers made efforts to disperse the crowd, telling them to leave or face arrest. When the protesters didn’t leave, the Guardsmen used tear gas, which was mostly ineffective due to the wind blowing in the wrong direction. As the situation escalated, some protesters began to resist, throwing rocks and tear gas canisters back toward the soldiers. Eyewitnesses at the scene placed the time at 12:24 pm, which is when they saw a National Guard sergeant named Myron Pryor begin firing his .45 pistol at a group of protesters. Almost immediately other guardsmen, at least 29 in all, opened up on the students with their rifles, firing an estimated 67 rounds in about 13 seconds. At the end of that volley 4 Kent State students[9] lay dead on the ground, with another 9 wounded.

students with bystanders

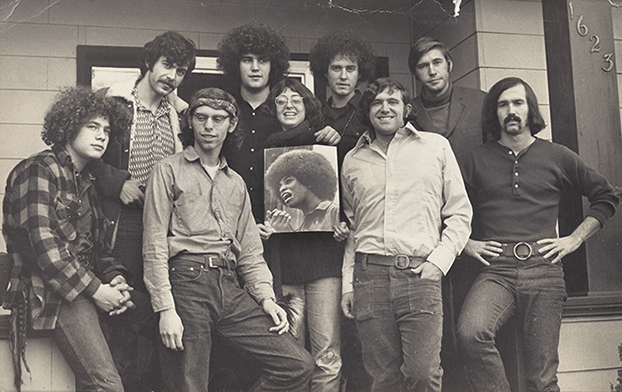

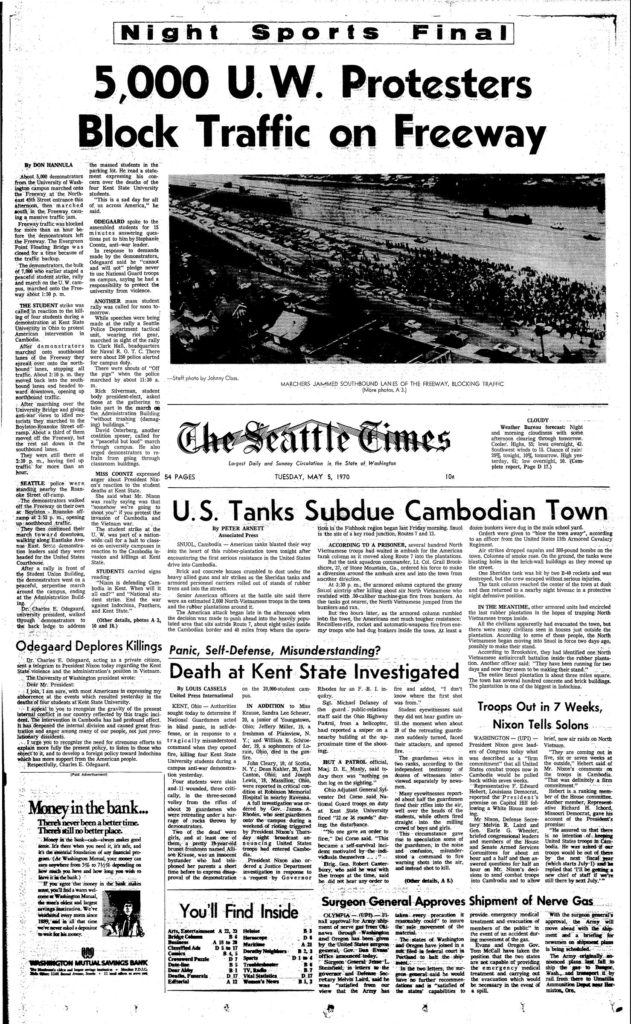

Almost telepathically, news of the Kent State tragedy spread through the student anti-war movement and college campuses across the country. Many students who were on the fence as far as joining the protest, were pushed off by what happened at Kent State. By the next day, Tuesday, May 5th, huge protests were taking place on every major university campus in the nation, and the University of Washington was no exception. Many professors shut down their classes, telling their students to join the protest, if that is what their conscience dictated; and there would be no penalty to their grade. One of my professors even said we would all get blanket A for the class, and to not worry about it. For my friends and I on campus, there was nothing to decide. At 10:30 AM that Tuesday morning, when around 7,000 students and faculty gathered in front of the HUB to coordinate the day’s protests and the strategy moving forward, we were there.

The protests and student strike on the UW campus following Kent State were called for by representatives from a coalition of groups, including the SLF, the Student Mobilization Committee (SMC)[10], the United Socialist Alliance, and the Associated Students of the University of Washington (ASUW). Chair of the coalition was newly elected ASUW president, Rick Silverman, who led the crowd that morning in a loud, informal vote on demonstration tactics and demands to be presented to University president Charles Odegaard. The demands ultimately agreed upon in the loose vote included: that Odegaard denounce the deaths of the 4 Kent State students, along with a pledge to never call the National Guard to the UW campus; that he terminate the University’s ROTC program and convert all ROTC buildings into memorials to the 4 dead Kent State students; that he end the University’s involvement in the war effort, including on campus military recruiting and “war oriented” research; and, in a nod to the Black Student Union, that he sever the University’s athletic relationship with BYU. The likelihood that Odegaard would agree to even one of the demands, much less all of them, was low, which left open the question of just how the students would respond. It promised to be an interesting afternoon.

Following the vote the students and protesters took off on an extended, peaceful march around the campus until they arrived at their ultimate destination, the school administration building, where President Odegaard had his office. Seeing the thousands of rowdy protesters assembling in front of the admin building, Odegaard understood he had to do something. Knowing his options could not include giving in to the students demands, he chose to come out and address the crowd with a bullhorn, instead reading to them the text of a telegram he had sent to president Nixon. In the telegram the UW president urged Nixon to recognize the severity of the tragedy at Kent State and to acknowledge the abhorrence of it felt by much of the nation. As read to the students from the telegram, Odegaard also encouraged Nixon to, “recognize the need for strenuous efforts to explain more fully the present policy, to listen to those who object to it, and to develop a foreign policy towards Indochina which has more support from the American people.” He then told the protesters that he would not and could not accede to their demands regarding ROTC and the conversion of its buildings, military recruiting policies, and BYU[11].

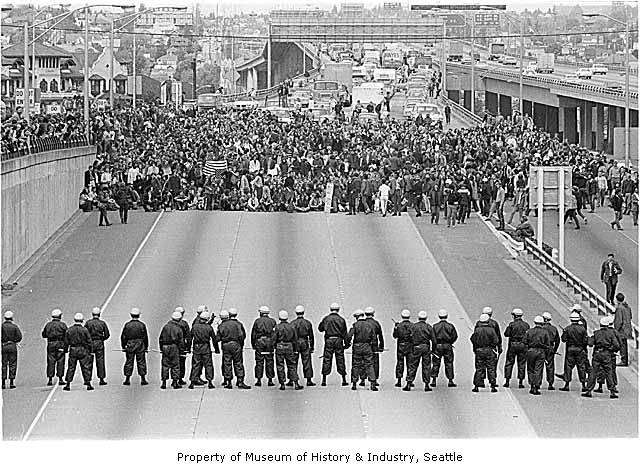

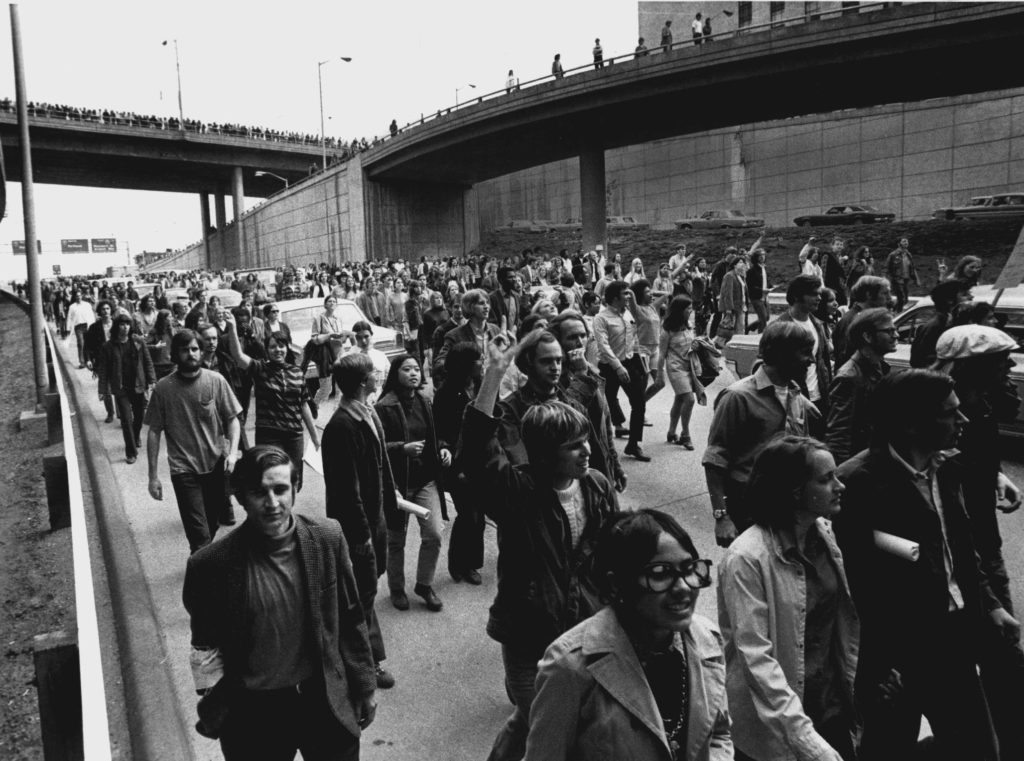

His Nixon telegram notwithstanding, Odegaard’s rebuff went down sideways with the demonstrators, which led immediately to a new vote by them on how they should respond. Urged on by the protest coalition leaders, they voted to continue the demonstration by marching off campus and out into the University District commercial area immediately to the west of the UW grounds. Emerging from the campus at NE 40th street, the protesters marched west one block to University Way; turned right (north) and marched 5 blocks to NE 45th street. At that point the crowd split up, with one thousand or so heading back towards campus, while the rest, about 6 thousand, continued west on 45th, past the legendary Blue Moon tavern[12], finally arriving at the I-5 South on ramp, which extends from the south side of 45th down towards the freeway. By then it was coming up on 2pm and the protest had been going on for over three hours; but the most dramatic phase was just about to happen. After pausing briefly at the on ramp, about 5,000 protesters made the abrupt turn south, down the ramp and toward I-5, obstructing traffic as they went. Upon reaching the freeway they then spilled out into the south and north bound lanes, completely blocking the traffic in both.

student protesters on I-5 at the Roanoke Street exit

Their ultimate destination being the Federal Courthouse in downtown Seattle, for the next hour or so the protesters worked their way south, down I-5 towards downtown, blocking traffic the whole time. Some frustrated motorists yelled at them from their cars, while others engaged them in conversation, but on the whole it was a peaceful march. Not expecting the I-5 tactic, the Seattle Police were a bit slow in responding, but by the time the students had advanced the mile from 45th to the Roanoke street exit they had rallied their forces, blocking further progress down I-5 with a squad of riot police arrayed across the southbound lanes. By then I-5 southbound traffic was backed up to Everett, about twenty miles north of Seattle, and it was obvious that to try and continue down the freeway would lead to violent confrontation with the police. After a few uneasy minutes stuck in front of the riot cops, the demonstrators took another loose vote and decided to end the I-5 occupation. They then took the Roanoke street exit and the regular Seattle surface streets to get to downtown. The day’s protest and march culminated in about 45 minutes of speeches in front of the Courthouse, condemning the war and the Kent State killings; after which the crowd broke up with the students and protesters making their way back to campus as best they could.

The next day, Wednesday, May 6th, students arriving for class were met at the campus entrances by student protesters urging them to skip their classes and go with the strike, which many did, joining the rally that was forming in front of the HUB. By noon nearly 10,000 students had gathered, thousands more than the prior day; and once more ASUW president elect Rick Silverman briefed the crowd, reiterating that their demands remained the same: that the University terminate its ROTC programs; that it end its involvement with the war effort; and that it also terminate its athletic relationship with BYU. Following Silverman’s briefing, President Odegaard again addressed the protesters, announcing that the coming Friday would be designated as a day of mourning for the slain Kent State students, and that classes would be shut down that day. He also urged the crowd to keep their protest nonviolent; that the point they were protesting to make would be better made in that fashion. Not quite believing that the protesters would take his advice, earlier that morning Odegaard had ensured that 3 busloads of tactical and riot squad police were called to campus and set up in the administration building, just in case they were needed.

May 5, 1970

Following Odegaard’s talk, which drew a mixed reaction from the demonstrators, first applause at his announced day of mourning, but then disappointment at his refusal of the other requests, another vote was conducted by Silverman on the question of tactics for the day’s protest. A small faction of radicals advocated for militant and violent action, like burning down the ROTC buildings, but the bulk of the students voted to keep the demonstration peaceful, and so it was decided. The protest would take the form of a peaceful march, not on the freeway this time, but across the Montlake Bridge south to Eastlake Avenue and toward Capitol Hill; the ultimate destination being the Seattle Municipal Building in downtown. Along the way the 8,000 or so protesters that left the UW were bolstered by thousands of additional students and demonstrators from Seattle University and Seattle Community College. By the time the throng reached the Municipal Building it had nearly doubled in size to approximately 15,000 people. Once there they were addressed by acting Seattle Mayor Charles Carroll, (elected Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman was on a visit to Japan at the time) who had to field demands from the protesters to shut down the entire city and join the students in a general strike. Carroll responded by reading a statement urging UW president Odegaard to allow Husky stadium to be used as the venue for a student/citizen forum to discuss Cambodia and Kent State. When he stopped short of acceding to the city-wide strike demand, several thousand protesters left the Municipal Building and started marching toward the I-5 freeway.

May 5th and 6th 1970

Once they realized that I-5 was again the target of the protesters, a squad of Seattle riot police rushed to block the closest freeway on-ramp, harshly pushing some of the protesters aside in the process. In response, the demonstrators simply altered their course and entered the freeway at another entrance on Madison street, a couple blocks away. They then proceeded to march north, back toward the UW, while shouting “Power to the People!” and “Cambodia!,” once again blocking the I-5 lanes and causing huge traffic back-ups. The police concentrated on clearing the northbound lanes first, which resulted in the protesters shifting to the southbound I-5 lanes for their northbound march, further exacerbating the traffic situation and pissing off multitudes of motorists. What then ensued was an almost comical effort by the police to anticipate the moves of the protesters as they moved north up the freeway, at times using the southbound lanes, at times the express lanes, and at times the northbound lanes, depending on where the police set up their road blocks. With their blocking tactics ultimately failing, the police then resorted to tear gas and billy clubs to clear the lanes, resulting in a number of injuries and arrests for the protesters; which succeeded in forcing most of the demonstrators off the freeway at the Roanoke street exit about a mile north of downtown. From there they made their weary way back to the UW campus, arriving individually or in small groups, only to re-form en masse in front of the HUB to plan the next day’s protests.

By the next morning, Thursday, 7 May, with the protesters meeting once again at the HUB, it was becoming clear that a schism was forming within their ranks, with a vocal, radical minority calling for violent tactics while the majority favored peaceful forms of protest. It’s been 50 years now, but I can still clearly recall one of these radicals addressing the thousands of protesters, telling us that we should be attacking the ROTC buildings on campus and burning them to the ground. With his proposal being met with a chorus of “boos” from the bulk of the students, the radical then dismissed the entire crowd, stating emphatically, “You’re all a bunch of motherfuckers!” The scene was almost comical; and, indeed, I recall laughing at that radical’s mass inclusion of the bulk of the protesters under the derisive “motherfucker” label. Making it not so humorous was the fact that those militant and radical views were shared by numbers of others within the protest ranks, a fact that would manifest violently later that day.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2021

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] John Edgar (J. Edgar) Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) of the United States. He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation, the FBI’s predecessor – in 1924 and was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director for another 37 years until his death in 1972 at the age of 77. Hoover has been credited with building the FBI into a larger crime-fighting agency than it was at its inception, and with instituting a number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized finger print file and forensic laboratories. More notoriously, later in life and after his death, Hoover became a controversial figure as evidence of his secretive abuses of power began to surface. He was found to have exceeded the jurisdiction of the FBI,and to have used the FBI to harass political dissenters and activists through his illegal “Counter Intelligence Program” (COINTELPRO), to amass secret files on political leaders, and to collect evidence using illegal methods. Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten others, including multiple sitting US presidents.

[2] Recently the subject of a movie entitled “The Trial of the Chicago 7” by writer/director Aaron Sorkin, which I would encourage readers to watch as it does a good job of capturing the spirit, not only of the Chicago 7 conspiracy trial, but of the times that spawned it, the Chicago 7 Trial stemmed from the anti-Vietnam War demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in the late summer of 1968. For an immediate reference the reader will find the Chicago 7 Trial well explained in Part I of this series linked above at the outset of this installment.

[3] Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the US during the 1960s. One of the principal representations of the New Left in the country at that time. SDS founders, including Tom Hayden, conceived of the organization as a broad exercise in “participatory democracy.” Launched in 1960 against the developing backdrop of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements, SDS grew rapidly through the decade of the ‘60s, eventually with over 300 campus chapters and some 30,000 members nationwide. At its 1969 convention the organization splintered because of rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing “revolutionary” positions on such issues as the Vietnam War and Black Power. From this split emerged the militant Weatherman, a much smaller and more radical left-wing group espousing violent revolutionary overthrow of the US government. Several bombings carried out by the group in the early to mid 1970s resulted in several of its members being placed on the FBI Most Wanted list for the rest of the decade.

[4] COINTELPRO (syllabic abbreviation derived from COunter INTELligence PROgram) (1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting American political organizations. The FBI has used covert operations against domestic political groups since its inception; however, covert operations under the official COINTELPRO label took place between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO tactics have been alleged to include discrediting targets through psychological warfare, smearing individuals and groups using forged documents and by planting false reports in the media; harassment; wrongful imprisonment; and illegal violence, including assassination. The FBI’s stated motivation was “protecting national security, preventing violence, and maintaining the existing social and political order”.

[5] An agent provocateur is a person who commits or who acts to entice another person to commit an illegal or rash act or falsely implicate them in partaking in an illegal act, so as to ruin the reputation or entice legal action against the target or a group they are perceived to belong to. The use of agents provocateur is a more or less standard intelligence tactic to accomplish the discrediting or destruction of a group deemed a threat.

[6] As were The Chicago Eight defendants before them, the Seattle Eight were charged under the anti-riot provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which made it a federal crime to cross state lines to incite a riot, as well as to conspire to cross state lines to incite a riot. The problem with charges of this kind lies in the fact that to convict the defendants requires proving what they were thinking, which is very difficult to do.

[7] George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who served as the 45th Governor of Alabama for four terms. He is best remembered for his staunch segregationist and populist views. A member of the Democratic Party, Wallace sought the United States presidency as a Democrat three times, and once as an American Independent Party candidate, unsuccessfully each time. Wallace opposed desegregation and supported the policies of “Jim Crow” during the Civil Rights Movement, declaring in his 1963 inaugural address that he stood for “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever”. In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. called Wallace “perhaps the most dangerous racist in America today.”

[8] The Ho Chi Minh Trail was a military supply route extending just over 1,000 miles from North Vietnam through Laos and Cambodia to South Vietnam. The route sent weapons, manpower, ammunition and other supplies from communist-led North Vietnam to their supporters in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

[9] The 4 students killed at Kent State were Allison Beth Krause, 19, Jeffrey Glenn Miller, 20, Sandra Lee Scheuer, 20, and William Knox Schroeder, 19. Nine others were injured in the shooting, one of whom suffered permanent paralysis.

[10] The Student Mobilization Committee was formed in 1966 “to coordinate opposition to U.S. involvement in the war in Vietnam among college and high school students.” Originally named The Vietnam Day Committee the SMC organized protests on campuses and in cities in addition to being one of the first groups that included civilians and soldiers alike. Based on a letter from 1969, the SMC had centers in 15 cities around the country but began to disband, like many anti-Vietnam groups in the early 1970s (1973) in conjunction with the U.S. beginning to withdrawing troops from Vietnam.

[11] Please see Parts I and II of this series, referenced at the outset of this article, for a complete description of the UW Black Student Union protests against the University’s involvement in athletic competition with Brigham Young University (BYU)

[12] Opened in1934, 4 months after the repeal of Prohibition, the Blue Moon is the first and oldest tavern in Seattle’s University District. An instant hit with students, the Blue Moon was one of the rare bars outside of the city’s Central District to serve African American servicemen during World War II. The tavern also provided a haven for UW professors who were caught up in the McCarthyist purge, such as Joe Butterworth, who used the bar as his writing desk. Its heyday continued into the 1950s and 1960s. Regulars included authors Tom Robbins and Darrell Bob Houston, poets Theodore Roethke, Richard Hugo, Carolyn Kizer, Stanley Kunitz and David Wagoner, and painters Richard Gilkey and Leo Kenney. Other visitors included Dylan Thomas, Ken Kesey, Allen Ginsberg and Mik Moore. During my time at the UW “The Moon” was a renowned counter culture and drinking hotspot, at which I imbibed a number of times. Today it is considered a historical landmark by many former students and artists.