Introduction

Not too long ago I picked up and read a book entitled “Protest on Trial: The Seattle 7 Conspiracy” by a local Seattle writer named Kit Bakke. The book tells of a thin slice of Seattle history, now largely forgotten, that took place fifty years ago: the story of the short-lived, radical left group called the Seattle Liberation Front (SLF). In February, 1970 the fledgling SLF sponsored a demonstration at the Seattle Federal Courthouse to protest the sentencing of the Chicago 7, a group of seven radical anti-war protesters who had been arrested and tried for conspiracy to incite a riot at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. The Seattle Courthouse demonstration itself turned into a riot, which ultimately resulted in the arrest and trial of seven core SLF members who, in their turn, became known as the Seattle 7.

I have a particular affinity for the story Bakke tells in her book, because I lived and experienced those times myself. The man most responsible for founding the SLF was my philosophy professor at the University of Washington, and I attended and personally experienced the Federal Courthouse riot that resulted in the ultimate arrest of the Seattle 7. Thus, it was fascinating for me to get the full history that Bakke relates in her writing. It allowed me to fill in the missing gaps in my experience and to put that experience into context. Don’t get me wrong, I was no hard-eyed New Left radical in those days, and was not a member of the SLF myself; but I was definitely left of center politically; was opposed to the Vietnam War, which in the early months of 1970 was being expanded by Richard Nixon; and I did my share of protesting, including a few testy moments with the cops.

In many ways those were heady times that even today retain a certain nostalgia for me; they were nothing if not exciting. The article that follows is written from my perspective of those times, filled in with the history from Bakke’s book and other sources. Incidentally, Kit Bakke is well qualified to tell this story. A former member of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and later the violent faction “Weatherman”, when it comes to tales of the radical 60s and 70s she knows whereof she speaks. She has done a marvelous job with her book, and for anyone who wants to learn the history of this brief era, or take a trip down memory lane (like me), I heartily recommend it.

Now, with all that said, return with me to the days of the early 1970s, when many of my generation wanted to change the world, and in some ways did. I invite you to read on…MA

____________________________

In January of 1970 I started the winter quarter at the University of Washington. One of the classes I took that quarter, along with several hundred other freshmen, was a Philosophy 101 class with a long haired and wild-eyed, left wing radical professor named Michael Lerner.[1] I didn’t know it at the time, but the 27-year old Lerner had only recently arrived in Seattle. Originally from Newark, New Jersey, his father was an Appeals Court judge in Newark, where the young Lerner attended both public and private schools, ultimately resulting in a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1964. After Columbia, he moved west to Berkley for graduate school at the University of California, where he got his New Left protest feet wet in the legendary Free Speech[2] movement; later becoming a leader in the Berkley chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS)[3]. In that capacity he got to know other New Left radicals who would become famous for their roles in the protest movement of the late 1960s, among them Jerry Rubin[4] and Tom Hayden[5].

With the breakup of SDS in 1969, Lerner, who had definite ideas of his own on how the revolution should advance into society, began looking for a place he could make those ideas take root. By 1969 the Berkley scene had settled into its own brand of revolutionary progressivism and wasn’t the new and fertile ground Lerner wanted. Seattle and the University of Washington were another matter, however. So, when UW offered him a one year contract as an assistant professor starting with the 1969 fall quarter, he packed up and moved north. Thus, it came to be that fate placed Michael Lerner directly in the path of an innocent, wet behind the ears freshman (me), who had unwittingly signed up for his philosophy class.

In those days Lerner wasn’t the only left wing firebrand with designs on Seattle and the UW as the place to foment a movement. In late December of 1969 three young radicals from Ithaca, New York hit town after a cross-country drive in a ’62 Chevy Biscayne they’d dubbed the People’s Chevy, so named because someone broke the key off in the ignition, which meant anyone could slide into the driver’s seat sans the key, fire up the Biscayne and drive off. Those three young radicals were Chip Marshall, Michael Abeles, and Jeff Dowd. A fourth New Lefter, a guy named Joe Kelly, had started the trip west with Dowd, Abeles and Marshall, but had to be dropped off in Chicago to deal with legal issues stemming from anti-war protests he’d been involved in earlier that summer. Marshall, Abeles, Dowd and Kelly all knew each other and were part of the anti-war/SDS/ New Left movement that centered around Cornell University in Ithaca in the late ‘60s. When SDS started to splinter in ’69, and its leadership coalesced into the new and violent faction self-styled as “The Weatherman,” Marshall and company knew, after a brief flirtation with that group, that it wasn’t the direction they wanted. So, after persuading a local judge to cancel criminal trespass charges against them stemming from an anti-war, spray paint sloganeering escapade they’d perpetrated against the Cornell ROTC building in return for a promise to leave town, that’s exactly what the group did.

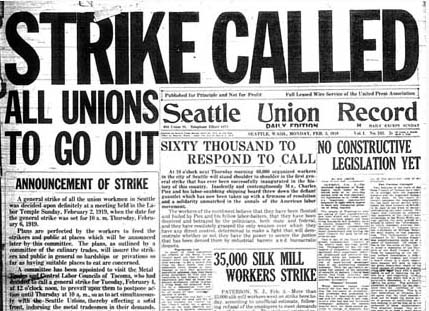

As a town and university not so dominated by already existing New Left forces and groups, Seattle and the UW had much the same appeal for Dowd, Marshall and Abeles as they did for Lerner. Also attractive to them, however, was Seattle’s role in the history of left wing politics in this nation, extending all the way back to the early 1900s. These guys were well aware, for instance, of the great Seattle strike of 1919, in which, after two years of World War I wage controls, more than 65,000 Seattle workers walked off their jobs for five days in demand of higher wages. Partially inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution[6] in Russia, the strike was supported by all the unions in Seattle, notably including the radical left International Workers of the World [7] (IWW, otherwise known as the famous Wobblies).

1919 general strike

As the first ever general strike in U.S. history, the Seattle walk out made national news at the time and inspired a considerable Red Scare backlash towards the strikers, with charges of “un-American” and “Bolshevik” being leveled toward them by conservative press and business. It also inspired similar strikes in other cities around the country; and from that time on up to the present Seattle has featured a strong labor movement and often a bent towards left-leaning politics. As they made their way west in the People’s Chevy towards the Puget Sound, none of this was lost on the radicals from Ithaca.

Of course, as I was sitting there in Lerner’s philosophy class on the first day of that 1970 winter quarter, I knew nothing of what I’ve just told you. The first indication that this would not be your ordinary philosophy class, other than the appearance of our professor, was in the text books we had to buy for the class; chief of which was a book called, “Reason and Revolution” by a guy named Herbert Marcuse.[8] Now, you might think that a course in basic philosophy would cover the classic philosophers like Plato, Aristotle and Socrates, but that wasn’t Lerner’s Philosophy 101 class. In 1970 I had never heard of Herbert Marcuse before, much less his book. Later I would find out that he is widely considered to be one of the Godfathers of what, during the 60s and 70s, was being called the “New Left,” and was a major influence on popular radicals of the day, such as Abbie Hoffman[9], Jerry Rubin and Angela Davis[10].

Now, for there to be a “New Left” there must have been an “Old Left,” and you might be wondering what the difference is. Simply put, and as near as I can tell, the “Old Left” referred mostly to the basic Marxist concepts of the working class and was primarily considered a movement of the “exploited worker,” as evidenced by worker’s unions of the early 1900s; classically represented by the socialist/communist views of the earlier mentioned International Workers of the World (Wobblies.) Due to the influence of later political theorists such as Marcuse, it was thought that the “worker oriented” model no longer epitomized the best approach for the Marxist agenda; the success of the post-World War II American middle class compounded by McCarthyism[11] had seen to that. Instead the emphasis became the poor, disenfranchised peoples of the world, the victims of racism and exploitation, classically represented in the ‘60s and ‘70s by the Vietnamese people, the Vietnam War and the plight of Blacks and other minorities in the United States; with university students becoming the primary agent of social change instead of exploited workers. Throw in liberal doses of “free love” and drugs (marijuana and LSD) and you have the “New Left” movement of that era, exemplified by Michael Lerner, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin and the crew from Ithaca, among others.

Looking back at it now, it’s apparent there was a method to Michael Lerner’s madness in teaching his radical philosophy class. Since coming to UW his intention had always been to create a dynamic coalition of the “New Left”, embracing the anti-Vietnam War movement, the various civil rights, “Black Power”[12] and anti-racist movements, the movement to “free” oppressed peoples both within the U.S. and the third world, and the Marxist-Socialist political philosophy espoused by Marcuse and others. The hundreds of students he was now inculcating with “New Left” ideals on a daily basis provided him with fertile recruiting ground. Though Lerner’s dynamic coalition had yet to actually take form, he already had a name for the movement he was creating: the “Seattle Liberation Front”. Within a few weeks the “SLF,” as it would soon be called, would be known to people all over Seattle and the Northwest, even extending into the hallowed halls of the FBI building in Washington DC.

Classes in that 1970 winter quarter had barely been underway for a week when Michael Lerner took the next big step in his creation of the SLF. Hoping to springboard enthusiasm and to gain steam for his organizational ideas, the professor had invited his old cohort from their Berkeley days, Jerry Rubin, to Seattle to speak at a meeting he was planning to hold on the UW campus. By January of 1970 Rubin had become famous in New Left and anti-Vietnam War circles, and notorious to middle class America, for his role in organizing and staging the anti-war protests at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in the late summer of 1968. The protests turned violent when the Chicago police, as ordered by Mayor Richard Daley[13], used tear gas and billy clubs on the demonstrators to disperse them. Across the five days of the Convention the country and the world were treated via national TV to the disgusting, violent images of protesters being beaten and brutalized by the riot police, while other demonstrators looked on, chanting, “The whole world is watching,” which, indeed, it was. Even otherwise conservative middle class Americans were put off by what they saw the Chicago cops doing to the protesters on their TVs. (It is very likely that the spectacle in Chicago cost the Democratic nominee for president, Hubert Humphrey, the 1968 presidential election, thus putting Richard Nixon into the White House; and we all know how that turned out.) [14]

Months after the Chicago protests, in March 1969, a grand jury issued indictments against Rubin and seven others from various parts of the anti-war and New Left movements in the country, charging them with the crime of “crossing state lines to incite a riot.”[15] The subsequent trial, which commenced in Chicago on September 24th, 1969, became a lightning rod for the anti-war and New Left movements, when one of the defendants, Black Panther leader Bobby Seale[16], was not allowed by Judge Julius Hoffman to choose his own attorney; or, since he couldn’t have his own attorney, to defend himself. Seale stridently and loudly protested what he viewed as the Judge’s unconstitutional rulings, which prompted Judge Hoffman to order the attending marshals to tie him up, gag him and chain him to his chair. For the next three days at trial Seale remained bound and gagged, though his efforts to escape his bonds and to talk despite being gagged caused considerable disruption in the court room. Finally Judge Hoffman ordered that Seale be tried separately from the other defendants, and so what had been the “Chicago Eight” was reduced to the “Chicago Seven,”[17] which is how they are mostly known to history now. Word of Seale’s plight spread like wildfire throughout New Left and anti-war circles all over the country, even prompting Graham Nash[18] (of CSNY fame) to write and record his song, “Chicago” decrying the Panther leader’s treatment and urging people to come to Chicago to protest it.

defendant Bobby Seale

Following Seale’s departure Rubin and the other defendants, chiefly his friend and Youth International Party (Yippies) co-founder Abbie Hoffman, continued to use the courtroom as their own personal theatre; mocking the proceedings with antic after antic while thoroughly pissing off Judge Hoffman in the process. As a result of the media exposure from the Chicago demonstrations and subsequent trial, by the time Michael Lerner brought Rubin to the meeting at the UW, the Yippee co-founder was an icon of the New Left. Thus, on the night the meeting was held, Saturday, January 17, 1970, at the Husky Student Union Building (the HUB), the hall was packed with students, faculty, New Left radicals and curious onlookers, including undercover FBI operatives, to hear Rubin speak. Also in attendance that night were the newly arrived radicals from Ithaca—Jeff Dowd, Chip Marshall, and Michael Abele.

With the exception of the FBI informants in the room, Rubin’s talk energized everyone in attendance with revolutionary zeal. Up to that point Lerner had never met Marshall, Dowd and Abele, but with the meeting at the HUB they all came together in one room for the first time. Because of his role as a professor and his impact on his students, Lerner was an obvious leadership choice for the fledgling movement; but he hadn’t counted on the impact the guys from Ithaca would have. Chip Marshall, in particular, was a polished speaker, experienced at handling and persuading people; qualities that were well demonstrated in a talk he gave to the crowd that night after Rubin was done. He also had a great deal of experience from his organizing activities on the east coast and, like Lerner, had definite ideas about how the movement should proceed. The two men met in person for the first time that night, after the event was over. As reported in Kit Bakke’s book, Lerner described their initial meeting as follows:

“I was approached at the end of the event by a Chip Marshall. Chip had just arrived in town, he said, a few days before…and he convinced me that he had something to offer in this whole thing, and that he could possibly be my ally in it. He reassured me that everything I said was totally what he wanted to do…He also said, ‘Oh, and I’ve got some other people that I came with.’ And I said, ‘Terrific!’”[19]

And so, on that January night in 1970, at the HUB on the University of Washington campus, the Seattle Liberation Front was born.

the Seattle Liberation Front

In Michael Lerner’s mind the form the SLF would take was much like that he had experienced in the Berkeley SDS chapter and the SDS overall, which emphasized a de-centralized structure with minimal national leadership and strong local chapters that ran their own shows. As with any other group, the members would get together for meetings, planning sessions and events, but did not necessarily live together, and were each responsible for their own livelihood. Chip Marshall, however, had a different idea. According to Lerner, Marshall, “…convinced me to do collectives, in which people would be more closely connected to each other, and work together…I thought, well, I don’t really have anything against that idea…Marshall’s idea of small groups could be a way of intensifying people’s commitment.”[20] Consequently, the first SLF collective was formed, which Marshall convinced Lerner should be called the “Sundance Collective,” after the Robert Redford character in the popular movie, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.” A short while later the first large SLF meeting was held, with over two hundred people in attendance. At this meeting, according to Lerner, “…people were very excited and they formed all these different collectives. So it seemed like, great, something is happening.”[21]

It wasn’t all excitement and good vibes at this first major SLF meeting, however, for also in attendance were several undercover FBI operatives. One of these FBI men in his report on the meeting stated, “A strange new unity had been formed among campus radicals at this meeting. SDS Weathermen were replaced by the Seattle Liberation Front in the eyes of the great majority of campus radicals. They were looking toward LERNER, MARSHALL and DOWD as the vanguard of the revolutionary movement in Seattle.”[22] Obviously, it wasn’t just the SLF movement that was gaining steam in Seattle at the end of January, 1970. Under the auspices of FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO),[23] which engaged in a wide array of covert activities, often illegal, designed to observe, infiltrate, discredit, disrupt and ultimately destroy groups that Hoover deemed to be un-American and threats to national security, the FBI had begun to martial its forces to destroy Lerner, Marshall and their nascent movement.

used against the SLF

Throughout the first couple of weeks of that winter quarter I was attending Lerner’s philosophy class about three times a week. During that time he spoke nothing about the SLF in our classes that I can recall, concentrating instead on Marcuse’s analysis of Marxist principles. Being too much of a novice, I wasn’t yet on the campus leftist rumor lines, and so I also had heard nothing about the Rubin meeting at the HUB on January 17th. It wasn’t until about the second week of February that word of the formation of SLF began to leak into the regular campus student body, but that doesn’t mean that Dowd, Marshall, Lerner and the gang weren’t working on their plans. At the HUB meeting a few weeks earlier Rubin had told them of the impending verdict in the Chicago 7 trial, which was expected to come down in mid-February. Radical groups around the country, including the SLF, were planning a coordinated action in their various cities under the banner “The Day After” (TDA) to protest the expected guilty verdicts. The protests would all be scheduled to take place “the day after” the verdicts were handed down, hence the common banner.

A problem was encountered, however, when Judge Hoffman threw all the nationwide protesters-to-be, as well as the Chicago 7 defendants themselves, a curve. The jury had been in deliberation for several days with no verdict being rendered, when Hoffman took matters into his own hands. On February 16th he sentenced the defendants to prison terms of two to two and a half years each for 159 separate counts of contempt of court recorded during the trial. The news of the “contempt” sentences spread like wildfire through the New Left and anti-war circles around the country, including the SLF, and the plans for the TDA protests were immediately implemented. With time being short, The SLF promptly sent a telegram to Seattle mayor Wes Uhlman and Washington state governor Dan Evans to communicate their intentions, stated in the telegram as follows: “The Seattle Liberation Front will hold a demonstration tomorrow in the Federal Courthouse. We intend to enter the courthouse and focus the attention of the Federal Courts on the suppression of blacks and the anti-war movement…” The telegram went on to say that the SLF had no intentions of being violent in their protest, and that they hoped they would be allowed to exercise their rights as citizens by entering the courthouse to address their concerns directly to the courts.

Their telegram sent, the SLF then got a massive poster and leaflet campaign going to announce the planned demonstration, set to take place at 2 PM Tuesday, February 17th at the Federal Courthouse in downtown Seattle. Fliers were passed out all over the UW campus and on every street corner in Seattle’s university district. Announcements were posted in every head shop, record store, and hippy haunt, as well as in the other college campuses around town. SLFers led by Jeff Dowd[24] busted in to an ongoing economics class being taught by a 62-year old professor named Henry Buechel, and proceeded to run up and down the aisles passing out their TDA fliers, completely disrupting the class in the process. In Beuchel, however, Dowd got more than he bargained for. The professor loudly asked his class if they would prefer to continue with his lecture, or if they would rather listen to the protesters. He then took off his jacket and challenged Dowd to a fight in the hall outside the classroom. Never having met professor Beuchel, I have no idea how tough he looked or was; but I saw Dowd many times in those days. I recall him as being a big, stout looking guy, boisterous in manner, and who, though himself white, sported a large, curly “afro” that made him very hard to miss in a crowd. Looking as he did, had he lived in an earlier time he could have been a great “street fighter” for the unions in their classic battles for worker’s rights against the company goons sent to stop them.

As near as I can tell, the Beuchel vs. Dowd fight never happened; but the story of the professor’s heroic, to some, stand against the radicals spread rapidly, ultimately arriving at the Oval Office in the White House. Upon hearing of Beuchel’s defense of his class, President Nixon wrote to him personally to congratulate him, telling him how much he admired him for his actions. For an organization that had barely been around a month, the SLF was becoming big news, and not just in Seattle.

I don’t specifically recall how I first heard that the TDA protest would be happening that Tuesday. As I was on the UW campus for hours every day, with all the leafletting and posting going on it would have been hard for me to miss. I do know that when I heard about it I was immediately intrigued and wanted to attend. I hadn’t yet arrived at the point of being a full-blown, New Left radical, but I had been developing definite anti-Vietnam War sentiments for some time, and so felt a kinship with the protesters on that level. I quickly surveyed my friends on campus, most of whom were old high school pals, to see who might want to go with me. Only one of them, a friend named Carl Larsen, agreed. Carl was a little wilder and crazier than I was, but not in a political sense. During our senior year in high school he once got suspended from class for a week because he showed up drunk at a school basketball game. Like many of us at the time, I think Carl had gone on to college after high school because he wasn’t sure what else to do, and it kept him from being drafted. One thing for sure, he liked a good time, and, like me, found the prospect of going to a real, live protest exciting. So, the next day, Tuesday, February 17th, that’s exactly what we did.

The Seattle Federal Courthouse and grounds occupy a full city block in downtown, between Spring and Madison streets on the east side of Fifth Avenue. Today it looks much the same as it did during the TDA protest, just over 50 years ago. The building itself is a large, imposing structure, some 10 stories high, and in 1970 it housed much more than courtrooms. Both senators from Washington state, Warren Magnuson and Henry Jackson,[25] maintained offices there. The Seattle offices of the FBI and the Secret Service were housed there, as well as the U.S. Marshall office and offices of the Ninth Circuit Appellate Court. In other words, much of the U.S. government law enforcement apparatus in Seattle resided in that Federal Courthouse. I certainly did not know that in 1970, and I don’t think many of the protesters did either; though I don’t think it would have mattered if they had.

By my recall, Carl and I timed our arrival at the protest to its announced 2 PM start, but by the time we got to 5th and Madison in downtown there were already well over 1500 protesters milling around the courthouse. The air was charged with excitement and anticipation; we could sense what was about to happen. Many years ago I wrote down my account of our experiences that day, and I’m publishing it here now, exactly as originally written:

Seattle Federal Courthouse, tear gas

cloud drifting over crowd

“We got to the site of the protest to find the Courthouse, which is not small, and its grounds, encircled by protestors. They were chanting, yelling and throwing rocks and balloons filled with paint at the Courthouse; every now and then you could hear above the din a bullhorn message coming from somewhere in the building, telling the protestors to cease and desist—a warning that went unheeded. Carl and I stood at the edge of this scene, taking it all in; observing, not really participating. A few feet, maybe twenty, in front of us, we saw Michael Lerner arguing with a girl that we knew named Hattie Hamlin. Hattie had come from our high school, but was now a sophomore at the UW. She was yelling at Lerner, attacking him for letting the rock-throwing protesters turn the demonstration violent. Lerner was defending himself, yelling back at Hattie repeatedly, ‘What would you do? What would you do?’ It appeared to us that Lerner was defending the rock throwing as appropriate under the circumstances. Just then someone bashed in the door to the Court-house and let tear gas loose into the building; God knows where that came from; I could see the billowing cloud start to drift out over the crowd. Suddenly, there was a commotion to our left. I looked west, down Madison street towards the ruckus, and could see people scattering in all directions. Through the gaps I could see, moving quickly up the street towards the courthouse, a phalanx of riot squad cops; perhaps one hundred or so. Fully equipped with helmets and billy clubs, these guys looked serious, and they meant business. Irresistibly, they plowed into the crowd, clubs held high, cracking heads and bowling over the protesters. Carl and I were at first stunned, but then full blown panic took over. We took off, running for all we were worth, down Fifth Ave toward Spring street, bobbing and weaving to avoid cops and other protesters. All around us people were falling down, screaming and yelling; while others jumped up on cars, running across them, anything to get away from the cops—a wild scene. The police fought their way through the crowd, got between the protesters and the Court House, and secured the grounds. I saw a few protestors walk up close to the cops and start calling them pigs right to their faces; deliberately trying to antagonize them to violence. Over 80 people were arrested that day and many were injured. Fortunately, Carl and I weren’t among them; we’d escaped our first protest and riot unharmed. We were fortunate.”

and many were injured”

A few years later, in recalling this incident and thinking of Hattie Hamlin standing up to Michael Lerner, taking him to task for letting the demonstration go violent, I had the realization that there are no loose rocks lying around in downtown Seattle. This riot was not an accident, I realized, but a deliberately planned event, with rocks and paint balloons brought in from outside especially for the purpose of pelting the Courthouse. To me, it looked for all the world like Lerner, Marshall, Dowd and the SLF had intended that the TDA protest be violent from the get-go. That’s how it seemed.

As many of us have learned through living, however, looks can often be deceiving.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2020

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] You will read much of Michael Lerner in this writing, but I think it is important to realize that the information provided here is all derived from a very short period of his life, the very early 1970s. Following his involvement with the Seattle New Left scene, across the balance of the 1970s and on into the 1980s and 90s he earned two PHDs, and created a rather remarkable career, including authoring several books, becoming an ordained Rabbi, founding a synagogue, founding and editing the liberal Jewish magazine Tikkun, becoming a friend to Muhammad Ali and even delivering a eulogy at his funeral and, incredibly, becoming a friend and mentor to none other than Hillary Clinton (until she severed the relationship due to being criticized for associating with Lerner due to his radical past.) The point is, 50 years have gone by since those radical days of the early ‘70s, and Lerner should be judged on his full life, not a small part of it.

[2] The Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a massive, long-lasting student protest which took place during the 1964–65 academic year on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley. The movement was informally under the central leadership of a Berkeley graduate student named Mario Savio. Savio is most famous for his passionate speeches, especially the “put your bodies upon the gears” address given at Sproul Hall, University of California, Berkeley on December 2, 1964.

[3] Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was a national student activist organization in the US during the 1960s. One of the principal representations of the New Left in the country at that time. SDS founders, including Tom Hayden, conceived of the organization as a broad exercise in “participatory democracy.” Launched in 1960 against the developing backdrop of the civil rights and anti-Vietnam War movements, SDS grew rapidly through the decade of the ‘60s, eventually with over 300 campus chapters and some 30,000 members nationwide. At its 1969 convention the organization splintered because of rivalry between factions seeking to impose national leadership and direction, and disputing “revolutionary” positions on such issues as the Vietnam War and Black Power.

[4] Jerry Rubin (July 14, 1938 – November 28, 1994) was an American social activist, anti-war leader, and counterculture icon during the 1960s and 1970s. There is far too much in Rubin’s fascinating life to be fully chronicled here, and I urge anyone interested to spend some time researching him on the internet. As far as his life and career relate to this article, starting in the mid 1960s, after dropping out of the University of California at Berkeley, Rubin became increasingly involved in social and anti-war activism, ultimately becoming a leader in the Berkeley New Left movements of that era. With fellow radical and friend Abbie Hoffman he co-founded the Youth International Party (known as the YIPPIE Party), which was more PR gimmick than a political party, designed more to attract media attention to New Left causes and issues than to getting anyone elected. In 1968 Rubin was catapulted to national attention for his role in planning and carrying out the anti-war demonstrations at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, for which he was indicted along with 7 other radicalsfor crossing state lines to incite a riot. The 8 radicals indicted became known as the “Chicago 8” and became New Left ‘cause celebres’ of the era. Throughout his radical career Rubin was most well known for the theatrics he employed to bring attention to the causes he espoused. For instance, on one occasion when called before the House Committee on Un-American Activities to testify on his communist affiliations, he showed up wearing Viet Cong pajamas with a toy M-16 rifle. On another occasion he arrived dressed in a Santa Clause outfit. By 1973 Rubin had given up his radicalism and morphed into a successful businessman and entrepreneur. He was a very early investor in Apple Computer and by the end of the 1970s was a multi-millionaire. From that point on to his death Rubin continued his successful business career in a number of capacities, employing the same energy he brought to the New Left, to his new undertakings. He died on November 28, 1994 after being struck by a car outside his apartment in Los Angeles.

[5] Thomas Emmet Hayden (December 11, 1939 – October 23, 2016) was an American social and political activist, author, and politician, best known for his major role in the anti-war, civil rights, and student radical movements in the 1960s. He authored the Port Huron Statement, which was the founding document of Students for a Democratic Society, and was one of the primary organizers of the anti-war demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, for which he, along with 7 others (including Jerry Rubin), was arrested and charged with conspiracy and crossing state lines to incite a riot; thus becoming one of the famous Chicago 8. In later years he ran for political office numerous times, winning seats in both the California Assembly and California Senate. At the end of his life he was the director of the Peace and Justice Resource Center in Los Angeles County. He was married to Jane Fonda for 17 years. Hayden died of a stroke in Santa Monica, California on October 23rd, 2016. He was 76 years old.

[6] The Bolshevik (or Russian) Revolution took place in 1917 when the peasants and working class people of Russia revolted against the government of Tsar Nicholas II. They were led by Vladimir Lenin and a group of revolutionaries called the Bolsheviks. The new communist government created the country of the Soviet Union.

[7] The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), members of which are commonly termed “Wobblies“, is an international labor union that was founded in 1905 in Chicago, Illinois, in the United States. The philosophy and tactics of the IWW are described as “revolutionary industrial unionism”, with ties to both socialist and anarchist labor movements. At their peak in August 1917, IWW membership was more than 150,000, with active wings in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Due to several factors, membership declined dramatically in the late 1910s and 1920s. There were conflicts with other labor groups, particularly the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which regarded the IWW as too radical, while the IWW regarded the AFL as too conservative and dividing workers by craft. Membership also declined due to government crackdowns on radical and socialist groups during the First Red Scare after World War I. In Canada the IWW was outlawed by the federal government. The IWW promotes the concept of “One Big Union”, and contends that all workers should be united as a social class to supplant capitalism and wage labor with industrial democracy.

[8] Herbert Marcuse (July 19, 1898 – July 29, 1979) was a German-American philosopher, sociologist and political theorist. In his written works, he criticized capitalism, modern technology, historical materialism and entertainment culture, arguing that they represent new forms of social control. He is the author of a number of books, including, “The Eros of Civilization”, “One Dimensional Man” and “Reason and Revolution.” In the 1960s and the 1970s he became known as the preeminent theorist of the New Left and the student movements of West Germany, France, and the United States; some consider him the “father of the New Left.” His works inspired many of the New Left radicals of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, including Jerry Rubin, Tom Hayden and Angela Davis, as well as Michael Lerner.

[9] Abbot (Abbie) Howard Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American political and social activist, anarchist, a socialist, and revolutionary who, with Jerry Rubin, co-founded the Youth International Party (“Yippies”). Hoffman became famous in 1968 when he was arrested and tried for conspiracy and inciting to riot as a result of his role in protests that led to violent confrontations with police during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, along with Jerry Rubin and 6 others. The group was known collectively as the “Chicago Eight”. While the defendants were initially convicted of intent to incite a riot, the verdicts were overturned on appeal. Hoffman continued his activism into the 1970s, and remains an icon of the anti-war movement and the counterculture era He committed suicide by a phenobarbital overdose in 1989.

[10] Angela Yvonne Davis (born January 26, 1944) is an American political activist, philosopher, academic, and author. She is a professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Ideologically a Marxist, Davis was a member of the Communist Party USA until 1991, Born to an African American family in Birmingham, Alabama, Davis studied French at Brandeis University and philosophy at the University of Frankfurt in West Germany. Studying under the philosopher Herbert Marcuse, a prominent figure in the Frankfurt school of Marxism, Davis became increasingly interested in left wing politics. In 1970, firearms registered to Davis were used in an armed takeover of a courtroom in Marin County, California, in which four people were killed. She was prosecuted for three capital felonies, including conspiracy to murder. Her legal plight at the time became a major focal point of the New Left in the United States, claiming Davis was innocent and was being railroaded by the government. After over a year in jail, she was acquitted of the charges in 1972, and has continued both her academic work and her domestic activism since.

[11] McCarthyism as a term refers to U.S. senator Joseph McCarthy (R-Wisconsin) and has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare, lasting from the late 1940s through the 1950s. It was characterized by the practice of making accusations of subversion or treason without proper regard for evidence, heightened political repression and a campaign of spreading fear of communist influence on American institutions and of espionage by Soviet agents, all of which were used by McCarthy in his congressional communist witch hunts. After the mid-1950s, McCarthyism began to decline, mainly due to the gradual loss of public popularity and opposition from the US Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren. The Warren Court made a series of rulings that helped bring an end to McCarthyism.

[12] Black Power is a political slogan, especially in the late 1960s and early 70s for groups such as the Black Panthers, and for various associated ideologies aimed at achieving self-determination for people of African descent. It is used primarily, but not exclusively, by African Americans in the United States. The Black Power movement was prominent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, emphasizing racial pride and the creation of black political and cultural institutions to nurture and promote black collective interests and advance black values.

[13] Richard Joseph Daley (May 15, 1902 – December 20, 1976) was an American politician who served as the Mayor of Chicago from 1955 to his death and the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party Central Committee from 1953 to his death. Daley is remembered for doing much to save Chicago from the declines that other rust belt cities such as Cleveland, Buffalo, and Detroit experienced during the same period. He had a strong base of support in Chicago’s Irish Catholic community and was treated by national politicians such as Lyndon B. Johnson as a pre-eminent Irish American, with special connections to theKennedy family. Overshadowing his career, however, are criticisms of his response to riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and his handling of the notorious 1968 Democratic National Convention during which Daley ordered his police to use violent tactics to disperse protesters who had gathered in Chicago to protest the Vietnam War. He also had enemies within the Democratic Party. In addition, many members of Daley’s administration were charged with corruption and convicted, although Daley himself was never charged. Richard Daley died on December 20th, 1976 when he suffered a massive heart attack.

[14] Richard Nixon (Republican) was elected President in the 1968 election over Hubert Humphrey on a promise of restoring law and order and claiming that he had a “secret” plan to end the Vietnam War. Instead, the initial years of his administration expanded US bombing to other countries around Vietnam, like Laos and Cambodia, which ignited the largest anti-war protests ever on college campuses around the country. In 1971 this resulted in the incident that destroyed Nixon ultimately, the leaking of the Pentagon Papers by former US Defense Dept analyst, Daniel Ellsberg. The Pentagon Papers were a compilation of classified government documents that traced the history of US involvement in the Vietnam War to the late 1940s and which demonstrated that many in the government had been aware for years that the war was unwinnable and on numerous occasions had misled and deceived the public. Besides charging Ellsberg with sedition, Nixon’s response was to create a secret group of operatives called the “White House plumbers” to initiate covert operations designed to find the “leakers” and “stop the leaks.” One of these operations was the break-in of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate office complex in June of 1972. The burglars were caught in the act, which led to the famous investigation by Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, as chronicled in their book “All the President’s Men” and in the movie by the same name. Their public investigation and the Congressional investigation of the White House cover-up resulted in Nixon’s resignation in August of 1974.

[15] The Chicago Eight defendants were charged under the anti-riot provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which made it a federal crime to cross state lines to incite a riot, as well as to conspire to cross state lines to incite a riot. The problem with charges of this kind lies in the fact that to convict the defendants requires proving what they were thinking, which is very difficult to do.

[16] Robert George Seale (Bobby Seale) (born October 22, 1936) is an American political activist. Inspired by the work of Malcom X, he and fellow activist Huey P. Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in October, 1966 in Oakland, California. Seale and Newton, in their view, created the Black Panther Party to organize the black community and express their desires and needs in order to resist the racism and classism perpetuated by the system. Seale described the Panthers as “an organization that represents black people and many white radicals relate to this and understand that the Black Panther Party is a righteous revolutionary front against this racist decadent, capitalistic system.” Essentially the Panthers were the manifestation of the “New Left” in the black community. Though the evidence against him was slim, Seale was charged along with the 7 other Chicago defendants with conspiracy to cross state lines to incite a riot at the Chicago Democratic Convention in 1968. He became internationally famous for his protests during the trial against Judge Hoffman’s refusal to allow him to be his own attorney, which resulted in Seale being bound, gagged and chained to his chair. Today Bobby Seale is 83 years old and lives in Oakland, California.

[17] The Chicago Eight became the Chicago Seven when defendant Bobby Seale was ordered by Judge Hoffman to be tried separately from the other seven, due to the uproar resulting when Hoffman ordered Seale to be bound, gagged and chained to his chair in the courtroom. The other seven defendants were Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, John Froines, and Lee Weiner—all anti-Vietnam War activists

[18] Graham William Nash (born 2 February 1942) is a British-American singer-songwriter and musician. Nash is known for his light tenor voice and for his songwriting contributions as a member of the English pop/rock group the Hollies and the folk-rock super group Crosby, Stills & Nash. He wrote his song “Chicago”, which appeared on his 1971 solo debut album, “Songs For Beginners,” to memorialize the injustice he felt was perpetrated against Bobby Seale in the Chicago 8 trial.

[19] Quoted from “Protest on Trial: The Seattle 7 Conspiracy” by Kit Bakke, pg 38

[20] Quoted from “Protest on Trial: The Seattle 7 Conspiracy” by Kit Bakke, pg 39

[21] Ibid, pg 39

[22] Ibid, pg 39

[23] COINTELPRO (syllabic abbreviation derived from COunter INTELligence PROgram) (1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrating, discrediting, and disrupting American political organizations. The FBI has used covert operations against domestic political groups since its inception; however, covert operations under the official COINTELPRO label took place between 1956 and 1971. COINTELPRO tactics have been alleged to include discrediting targets through psychological warfare, smearing individuals and groups using forged documents and by planting false reports in the media; harassment; wrongful imprisonment; and illegal violence, including assassination. The FBI’s stated motivation was “protecting national security, preventing violence, and maintaining the existing social and political order”.

[24] Jeff Dowd (born November 20, 1949), is another of the SLF radicals who went on to a remarkable career after his New Left days in Seattle. Briefly, starting in the late ‘70s Dowd worked with a chain of movie theatres in Seattle to bring in interesting movies, one of which was 1984’s Blood Simple, the first feature film by the now famous brothers Ethan and Joel Cohn, who would go on to write, produce and direct such films as Fargo, No Country for Old Men and O Brother, Where Art Thou, among others. Blood Simple didn’t do well generally at the box office, but did do well in Seattle; and when the Coen brothers looked into why they found it stemmed from Dowd’s promotional efforts. Dowd and the brothers became friends and a short while later he moved to LA to continue his career in film marketing, distribution and producing. Dowd’s larger than life personality made a huge impression on the Coen’s, and that impression inspired the character “The Dude”, played by Jeff Bridges, in their 1998 film The Big Lebowski. That film even today, over 20 years after its release, is still a cult classic, with fans gathering in annual conventions to celebrate it. While Dowd’s inspiration of “The Dude” is his biggest claim to fame, he is also recognized for being a film marketing and distribution guru for decades, a producer, a producer’s representative, a writer, and a founding member of the Sundance Film Festival; all in all, a productive life.

[25] Warren Grant “Maggie” Magnuson (April 12, 1905 – May 20, 1989) and Henry Martin (Scoop) Jackson (May 31, 1912—Sept 1, 1983) were both long time politicians, Representatives and Senators from the state of Washington. Magnuson, a member of the Democratic Party, served as a U.S. Representative (1937–1944) and a U.S. Senator (1944–1981) from Washington. He served over 36 years in the Senate, and was the most senior member of the body during his final two years in office. Jackson, also a Democrat, served as a U.S. Representative (1941–1953) and U.S. Senator (1953–1983). A Cold War liberal and anti-Communist Democrat, Jackson supported higher military spending and a hard line against the Soviet Union, while also supporting social welfare programs, civil rights, and labor unions.

2 Responses

Excellent article. Calls to mind my days as Deputy Chairman of the Peace and Freedom Mobilization, 1969-70 in Iowa.

Thanks, Kenn! I can imagine it does. We old protesters have a unique and valuable perspective, and I think it is good to share it.