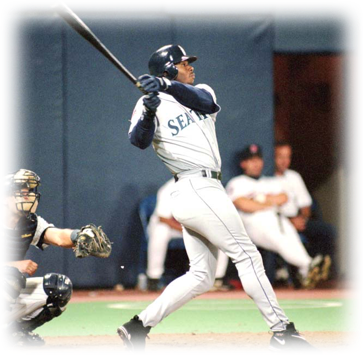

Introduction: A few days ago, in the 8th inning of the 2nd game of the Seattle Mariners season opening series against the Oakland A’s, played in Tokyo Japan, Ichiro Suzuki grabbed his glove and ran out to his customary position in right field for the last time. The future Hall of Famer had finally come to terms with the fact that he simply couldn’t play the game at the stellar level he and baseball fans all over the world had been accustomed to, and marveled at, for the last 28 years (19 in the Major Leagues and, before that, 9 seasons for the Orix Blue Wave in Japan.) We in Seattle were very fortunate to have witnessed Ichiro in his prime, when he starred for the Seattle Mariners from 2001 to 2012. During those years with the M’s, the best player to have ever come to the Majors from Japan did things on a baseball field we had never seen before. In 2001, Ichiro’s first season in the Majors and with the Mariners, he won not only the batting title (.350 Avg), but also the American League Rookie of the Year award AND the American League Most Valuable Player award, joining Fred Lynn (Boston Red Sox, 1975) as one of only two players in Major League history to have won both awards in the same season. In addition, Ichiro is the ONLY player in Major League history to record 10 consecutive seasons (2001-2010) with 200 or more hits. (Pete Rose also had 10 200 hit seasons, but they weren’t consecutive.) In 2004 he once again won the batting title with a .372 Avg, and in the process shattered the all-time record for hits in a season, set by George Sisler in 1920 (257), with 262 hits. He was a ten-time All Star and won the Gold Glove award as the best defensive right fielder in the American League ten times. He holds the American League record for hitting streaks of 20 or more games (7), and in 2016, while playing for the Miami Marlins, became just the 30th player in Major League history to record 3,000 hits. Counting his seasons in Japan, Ichiro accumulated the astounding total of 4,367 hits during his career—over 100 more than Pete Rose recorded in his 24 Major League seasons; and when he is eligible, he will be a shoe-in first ballot Hall of Famer. To honor Ichiro Suzuki and his marvelous career, I am publishing here in 3 installments my account of his thrilling assault on George Sisler’s hit record during his 2004 season with the Seattle Mariners. I hope you enjoy it—please read on…MA

In Honor of Ichiro–Part I

I first heard of Ichiro Suzuki around spring training of the 1997 baseball season. He trained with the Mariners that year in Arizona and word was that the kid was good. I remember reading that Lou Piniella liked him, liked his batting eye and arm, and thought he could make it in the Big Leagues. After that ’97 spring training Ichiro went back to Japan and played the next few years with the Orix Blue Wave of the Japanese Pacific League. Though he was spectacular in Japan, winning something like seven batting titles, not much was heard of him in the States until the winter of 2000-2001. That is when the Mariners, in a closed bidding process, acquired the rights to him and signed him to a three-year deal. The Mariners touted him as the Second Coming and waved him in front of us fans as the greatest thing since Junior had donned Mariners flannels. Yeah, right. Not a one of us fans believed it. As good as Junior? No way!

I have ever seen.

You have to understand that in the winter of 2000-2001 we Mariners fans were an embittered lot. You would think otherwise, considering we were now playing our home games at the magnificent Safeco Field and were coming off a season in which we made it to the ALCS; but the fact is we were smarting from the loss of our stars. In ’98 Randy Johnson had left at the trade deadline claiming the Mariners didn’t show him sufficient respect by making an offer to him anywhere close to his market value. Thus, he sulked the first half of the season and basically tanked it with barely a .500 winning percentage. (Randy would probably dispute that he tanked it–the stats prove otherwise.) After he was traded to Houston he went 10 and 1 for the Astros down the stretch, helping them to the playoffs. That pissed us all off here in Seattle.

Then came the winter of ’99-2000—the winter of our discontent. The Mariners did the unthinkable by trading Ken Griffey Jr. to the Cincinnati Reds. We had all watched Junior grow from the talented high school kid in 1989, to the man who by 1999 had just completed what is arguably one of the greatest 4 year stretches by any hitter in the history of baseball. Across the 4 seasons from 1996 – ’99 he averaged 52 home runs per season, while driving in 142 runs per season, and scoring 123. Man, that’s ‘Babe Ruth in his prime’ type production! And now Junior was gone. No more amazing catches in center field; no more majestic, parabolic, upper deck shots; no more sweet, left handed swing. Ken Griffey Jr. in his prime was the greatest baseball player I have ever seen. The team’s lame explanation for why they had to trade him, and with a year to go on his contract no less, just made no sense to Seattle fans. Like rubbing salt into an open wound, it just upset us more.

Seattle Mariners

What’s worse is that supposedly Junior was distraught that, after so many years in the homer friendly Kingdome, Safeco Field was not a hitter’s park. Tell that to Rafael Palmiero! He has parked so many balls into the right field seats at “The Safe” that he lists it as his favorite road park to hit in. One time I went to a Mariners-Rangers game at Safeco with a friend and I bet him a pint of Häagen-Dazs ice cream that Palmiero would hit one out. Knowing that the odds favored him, my friend eagerly took the bet–I knew he would lose. Palmeiro homered in his first at bat. The fact is that Safeco was tailor-made for Junior’s swing as a left-handed hitter. Had he stayed he would have figured that out.

Then came the winter of 2000-2001, and Alex Rodriguez leaves town with a 10 year $250 million deal in his pocket from the Texas Rangers; and then says it’s not about the money. Why didn’t he stay with Seattle then? Not about the money my ass!!! The more these guys talk, the more forked their tongues become. That’s how it seems to the Mariners faithful.

Yes, being a Mariners fan has definitely been a tough road.

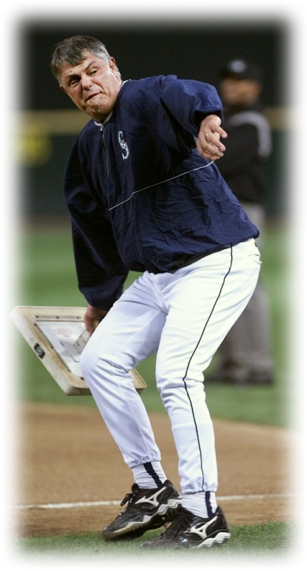

After every winter comes a spring, however, and that spring of 2001, as the Mariners trained in Arizona, we were getting our first samplings of Ichiro. Though named Ichiro Suzuki, he was known by his first name only. I heard that was because when he started playing in the Japan Leagues there were so many players named Suzuki that to separate them out the manager told him they’d use his first name only on his jersey. Supposedly Ichiro didn’t like this at first, but his name caught on; so now it’s just “Ichiro” and everyone knows who you are talking about. As spring training progressed Mariners Manager Lou Piniella became concerned because he wasn’t seeing Ichiro “pull” the ball much in batting practice or in games. He asked Ichiro to start pulling the ball a little, just so Lou could see that he could do it. Next game Ichiro pulled a long home run to right field in his first at bat. That was enough to satisfy Lou, and the Mariners had a new right fielder.

Lou Piniella

Spring training ended and the Mariners came north to play their first game of the 2001 season against the Oakland A’s at Safeco Field. My wife Tammy and I attended the game that night; it was cold, with the temperature in the 40s. By the eighth inning the M’s were losing 4 to 1, and Tammy and I were frozen to the core. Then Ichiro came to the plate and dropped a perfect bunt down the third base line. Like a flash, he was out of the batter’s box and easily beat it out. I had never seen anyone run that fast in my life. Maybe there was something to this guy. Ichiro’s bunt single ignited a rally and the Mariners came back to win 5-4. The win was nice, but it’s just one game. We’ll see.

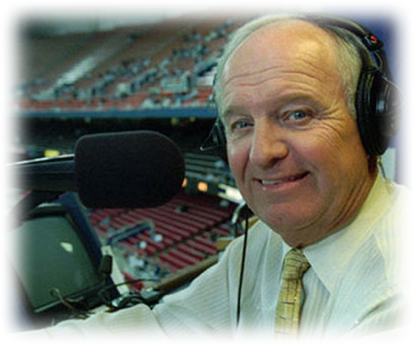

A few days later in Oakland the M’s played the A’s again; a game I watched on TV. At one point in the game the A’s had Terrence Long on first base, and the next A’s hitter lined a single to right field. Long rounded second and figured he could easily make third base on the hit. Meanwhile, out in right field, Ichiro got to the ball quickly, fielded the ball cleanly, and unleashed a throw to third base that was more a laser beam than a throw; the ball never getting more than 6 feet off the ground and arriving at third base right on line. Long was out by three feet. Dave Niehaus, the Mariners long time broadcaster, went bonkers. He had never seen such a throw! None of us had. Since then if you just say “The Throw” to any Mariners fan they will instantly know what you are talking about. We had been introduced to Ichiro Suzuki.

broadcaster Dave Niehaus

For Mariners fans the 2001 season was amazing, but bittersweet. I have never seen a baseball team play so consistently well, and for such a long time. The Mariners made mincemeat of the AL West and, indeed, the entire league. By the All Star break they had a twenty game lead and kept it the rest of the way. They executed perfectly everything Lou wanted them to do, had great pitching, superb defense and got every break. We had never seen anything like it and it seemed the Mariners were destined for their first World Series. We had every reason to think this; and much of the reason for this success was Ichiro. As the season went on it was obvious he was a superstar. He led the league in hitting the entire year. He led the league in steals. And he had the best outfield arm I have ever seen. He would take the American League MVP award that year as well as Rookie of the Year; he would win the batting title with a .350 average and got the Gold Glove for his outfield play. The guy was incredible. He could do it all except hit for power—and sometimes he even did that.

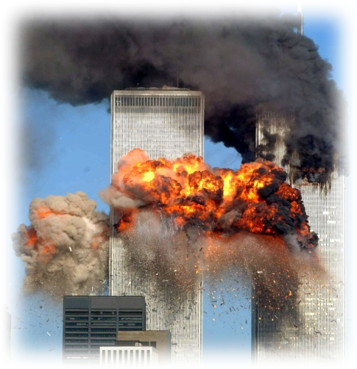

In early September the Mariners were close to clinching the AL West title, and were playing the Angels on a Monday night. The game ended, as so many had that year, with another Mariners win. The last play was a diving catch in left field by Charles Gipson. Lou used him often as a late inning defensive replacement and plays like that obviously justified the M’s skipper’s judgment. As I went to bed that night visions of a World Series in Seattle danced in my head. Early the next morning my wife shook me awake: “You’ve got to come watch TV!” she said. The tone in her voice was urgent. I immediately got up and went into the living room. On the TV screen I saw smoke billowing from the World Trade Center; and then the second plane hit, and it was obvious this was no accident. We were under attack!

I followed the news throughout the day. The Pentagon was hit and then the fourth plane crashed in Pennsylvania. The World Trade Center towers collapsed. Nearly three thousand people died; almost double the loss of the Pearl Harbor attack that launched us into World War II. The initial terror was followed by confusion and then by rage. Who would do such a thing? What will we do about it? The financial markets panicked and plane flights were cancelled. The country ground to a halt.

were under attack.

So did the baseball season.

It was a week before play resumed in the Major Leagues. Once it did the Mariners continued to win and quickly clinched the American League West pennant. They finished the regular season with 116 wins, an American League record, and tied for most in the history of baseball! No team had won that many games since the 1906 Chicago Cubs! As great as this was, things were not the same. There was a palpable pall over everything. Life had gotten real serious, and baseball, it seemed, was not nearly as important as it had been just a few days earlier. By the time the playoffs started the Mariners were a distracted team. They barely got by an inferior Cleveland Indians team in the Divisional Series and then met the Yankees in the American League Championship Series. The first two games were at Safeco Field. We lost the first, and I attended the second and witnessed us lose on a Mike Mussina five hitter. We were down 0-2 and the series was to go to New York for the next three. Lou put on a brave face and guaranteed the series would return to Seattle; and while the papers made much of this, I didn’t think it would happen.

To make things worse, Lou let the team visit the World Trade Center Ground Zero site before the first game in New York. Realistically, I don’t know how you would prevent it; but I thought it was a big mistake. The last thing we needed was the team feeling sorry for New York. By then the whole country did. Doing a little thing like beating the Yankees for the American League Pennant and going to the World Series was nothing compared to the overwhelming sense of loss and disaster that must have been occasioned by visiting the World Trade Center site. The team had lost the edge; its focus was gone. The series never made it back to Seattle, Lou’s promise to do so notwithstanding. His words had vaporized, like so much Ground Zero dust; so did the hopes of us fans. A gray and cold winter loomed.

Sometimes today I look back at that season; it’s easy to agree with what happened to the Mariners. After all, life and death are so real, and baseball is only a game. So many lives were lost—so many people robbed of their loved ones in the twinkling of an eye. They had woken up that September morning, had gone to work, like any other morning; then poof…gone…just like that. These were not long goodbyes. But then I think, in the bigger picture, what is life but a game? It’s got freedoms and barriers. It has purposes. I lead a very busy life. The things I do are important; but I will take several hours and watch a baseball game, on TV or at the ballpark. I will make time for it, but sometimes I will think, “What am I doing, wasting my time watching this game?” Particularly when the Mariners stink up the joint. But when I sit back and look at it, baseball and life are, alike, games. They both can get pretty serious at times.

Steve Bartman, the fan in Chicago who deflected the foul ball down the left field line at Wrigley in the 2003 playoffs, found that out. He stuck his hand in the way and prevented Moises Alou from getting a key out in the late innings, and the Cubs went on to lose the series. The long-suffering Cub fans were furious. Verbal abuse and death threats became the lot of the unfortunate Bartman. I think he even had to move. Or look at poor Bill Buckner. In the ’86 World Series he let the Mookie Wilson ground ball go between his legs thus costing the Red Sox their first World Championship since 1918. Despite an otherwise stellar career Buckner was the epitome of evil in Boston for many years thereafter. That play ruined his life. Finally, some rock group wrote a song called “Forgiving Buckner” in an effort to shed the upset of that moment.

And in life… the World Trade Center and 9/11. It seems we will never get over it. But life, if you can get exterior to it and understand it, like baseball, is a game. The seriousness is occasioned by the idea that what you are losing is all you have, or will ever have. The seriousness is occasioned by the idea of scarcity. We all know our chances in life are few. We all know we have but one body. We all know we have but one life.

We all know it. But maybe it’s not true.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2019

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

4 Responses

Yay thank you! Great piece. I read through it very well and fast!

Ichiro!

Thanks, Scott! Ichiro was/is one of a kind…a great player!!!

Hi Mark. This is a fabulous Blog you wrote!! That was a great and frustrating baseball season and the unfortunate circumstances of that attack effected everything from then on. However, we had a new and exciting player in Seattle and it was a pleasure to watch Ichiro do his magic for years to come.

Thanks, Stan!

As you and I have discussed many times, I truly believe 9/11 cost us our first Series. But life goes on…Ichiro had a fabulous career and I am glad that we got to witness the most incredible parts of it…10 consecutive 200 hit seasons, 10 All Star selections, 10 Gold Gloves, 2 batting titles and an MVP award…pretty amazing!