_____________________________

Not too long ago, while doing some research, I came across an article written in 1963 by Dr. Martin Luther King. Today the article is called “Letter From A Birmingham Jail,” and it was written by King during one of his civil rights campaigns in Birmingham, Alabama. As the article’s title indicates, it was written while the civil rights leader was sitting in jail, having been arrested during one of the campaign’s protests, in response to published criticisms from white Birmingham clergymen who claimed that in taking to the streets and engaging in civil disobedience King and his followers were pursuing the wrong course. Though they agreed that racial injustice and inequities existed, the white clergymen felt that the proper place for King to carry on his crusade was in the courts, and not in the streets. (If you have not read King’s article itself, I have published it in full in this blog and you can access it here: http://fromanativeson.com/2018/04/05/martin-luther-king-letter-from-a-birmingham-jail/ )

The eloquence and wisdom of King’s writing speaks for itself, far beyond anything I could say about it here; but there is an idea that he refers to in his article that I find especially significant, and that is the concept of what he and other philosophers call “natural law” or “moral law”(also “eternal law” or “God’s law”—all efforts to say the same thing).” King explains this concept in this quote from his article:

“You express a great deal of anxiety over our willingness to break laws. This is certainly a legitimate concern. Since we so diligently urge people to obey the Supreme Court’s decision of 1954[1] outlawing segregation in the public schools, at first glance it may seem rather paradoxical for us consciously to break laws. One may well ask: ‘How can you advocate breaking some laws and obeying others?’ The answer lies in the fact that there are two types of laws: just and unjust. I would be the first to advocate obeying just laws. One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws. I would agree with St. Augustine [2] that ‘an unjust law is no law at all.’ / Now, what is the difference between the two? How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man-made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas [3]: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. Segregation, to use the terminology of the Jewish philosopher Martin Buber [4], substitutes an ‘I–it’ relationship for an ‘I–thou’ relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things. Hence segregation is not only politically, economically and sociologically unsound, it is morally wrong and sinful.”

When I read this section in King’s article I immediately stopped, and then read it again—and then again. Of course, what you are looking at in those few sentences is the philosophical underpinning of the entire Civil Rights movement in America, Mahatma Gandhi’s [5] nationalist independence movement in India across the 1930s and 40s, the late 1700s revolutions in what is now the United States and in France; and before that going all the way back to Magna Carta (England, 1215) and philosophers in ancient Greece. And I believe, moving into the future, it will be the philosophical basis of every great movement towards freedom yet to come.

Why would this be so?

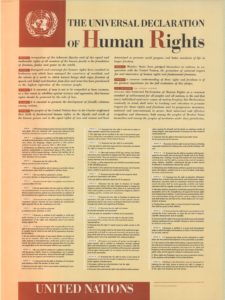

Because the statement that there is such a thing as “natural law” is, quite simply, true. I believe this and, speaking just for me now, I know it is the case. Every effort by man on planet Earth to enumerate his unalienable rights, from the U.S. Bill of Rights and Thomas Paine’s “The Rights of Man” [6] in the late 1700s, to the English Magna Carta in 1215, in which the traditional right of habeus corpus[7] is majorly upheld and reinforced; all the way up to the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights[8] in 1948, are simply efforts to illuminate and describe these “natural” or “moral” laws. Whether some of these efforts succeed at this better than others is not for me to say; but that is what they are, and if we truly want world peace the effort to institutionalize these “natural laws” should be lauded and supported.

Speaking of world peace, understanding the above sheds major light on just how that long sought condition can be accomplished. At first glance it can appear that the assertion of natural rights and law can precipitate violence. In insisting on their natural rights and in refusing to follow “immoral law” King, Gandhi and their followers elicited violent responses from their suppressors in the United States and the British Empire. As the white Birmingham clergymen accused King of, it appeared that the violence was the result of the protests. This, however, is a false observation; for as King pointed out in his article, and as St. Augustine stated much earlier, “…an unjust law is no law at all.” In these examples with the U.S. and Great Britain vis-à-vis the Civil Rights Movement and the Indian Nationalist Movement, both the oppressors in enforcing the unjust laws, and the oppressed if they went along with them, would be, alike, sinning. The oppressed are moral and duty bound to not follow “unjust” laws, just as those in power are moral and duty bound not to enforce them. Looking at it this way assigns the responsibility for violence to those to whom it truly belongs; those who enforce unjust and immoral laws with violence. This also explains why both King, and before him Gandhi, were so adamant in insisting that their movements be non-violent. They had to, lest they and their people become inadvertently involved in violating the natural rights of their oppressors. They both intuitively understood that would be sinful. It is an interesting aside that in this we witness one of the major reasons for the collapse of otherwise good and sound movements on this planet: they start to engage in actions that violate the natural rights of those opposing them, and therefore cave themselves in while, at the same time, giving justification to those who wish to wipe them out.

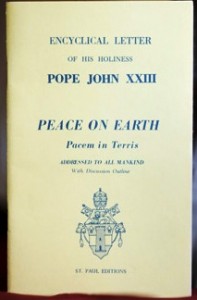

Probably the theologian in relatively recent times who had the best grasp of Human Rights and Natural Law as a necessary condition for world peace, and who wrote eloquently about it, was none other than Pope John XXIII. Though he only held the post for 5 years (1958-1963) Pope John is one of the most beloved and respected pontiffs in modern history. In April of 1963 he published his landmark encyclical [9] Pacem in terris (Peace on earth), in which he explained his view that the accomplishment of world peace depended in the main on the leaders, governments and people of the world maintaining what Pope John called “…diligent observance of the divinely established order.”

Before I go further I think it is important to understand the context of the times in which Pope John issued Pacem in terris. The world had only recently breathed a sigh of relief when the most dangerous two-week period in human history, the Cuban Missile Crisis, was successfully resolved in late October, 1962. Pope John himself had played a significant role in its resolution, when on October 25th, at the height of the Crisis, he issued his plea for moral responsibility by world leaders, in which he said:

“We implore all rulers not to remain deaf to the cry of humanity for peace. That they do all that is in their power to save peace. They will thus spare the world from the horrors of a war whose terrifying consequences no one can predict. That they continue discussions, as this loyal and open behavior has great value as a witness of everyone’s conscience and before history. Promoting, favoring, accepting conversations, at all levels and at any time, is a maxim of wisdom and prudence which attracts the blessings of heaven and earth.”

Pope John’s message was widely published around the world, even in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. Indeed, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev [10] would later state that at the time it was issued Pope John’s plea was the “only gleam of hope” in an otherwise dark situation. A few days later President Kennedy and Khrushchev negotiated a successful conclusion to the Crisis when the Soviets agreed to remove their missiles from Cuba in exchange for a U.S. pledge to not invade that island and to remove its missiles from Turkey.

With the Crisis resolved, and knowing that he only had a short time to live due to terminal stomach cancer, Pope John next turned his attention to doing everything he could to promote an end to the Cold War and the arms race and to bring peace to Earth. This led to a remarkable yet little known series of exchanges initiated by the Pope to promote communication between President Kennedy and Premier Khrushchev. To accomplish this Pope John sent a messenger to a Catholic pacifist magazine publisher in the U.S. named Norman Cousins[11], and asked him if he would be willing to serve as his emissary to Khrushchev in the Soviet Union. The purpose would be to deliver Pope John’s messages to the Premier, to represent the Pope to him, and to deliver the Premier’s communication back to the Pope. In the process of setting this up Cousins contacted the U.S. State Department to coordinate with the Kennedy administration, and so in effect became Kennedy’s emissary as well.

Cousins would make two trips to see Khrushchev on behalf of Pope John and JFK, and before the second one, in early April, 1963, he visited the Vatican and was provided with a special advance copy of Pacem in terris (which had not been broadly published yet) to deliver to the Soviet Premier. At the time Pope John was critically ill; and though Cousins had hoped to meet with the pontiff personally, he was not able to. Nevertheless, with the Pope’s encyclical in hand, Cousins travelled to the Soviet Union and fulfilled his mission of hand delivering it to Nikita Khrushchev.

Though it is hard to say it was caused solely by Pacem in terris, across the next few months there was a noticeable thaw in Soviet-American relations. Pope John succumbed to his cancer on June 3rd, 1963, and exactly one week later, on June 10, 1963, JFK delivered what is probably his greatest speech ever at the Commencement ceremony for graduating seniors at American University in Washington DC; a speech known today as Kennedy’s “Peace Speech.” The speech was stunning for its time because it called for Americans to completely reevaluate their considerations about both the Soviet Union and the subject of peace, something unheard of for the Cold War era. A few weeks later negotiations between the United States, the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union resumed on a treaty, the purpose of which was to ban the testing of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. The treaty (known as the Limited Test Ban Treaty), which had been under on and off negotiation for the prior 8 years, had hung up on a disagreement over the number of inspections the U.S. required of Soviet nuclear testing sites. Khrushchev in particular had been upset over what he felt were shifting U.S. demands as to the number of inspections, so much so that negotiations had broken off a few months earlier in March.

With the resumption of the negotiations the U.S. and the Soviet Union very rapidly resolved the points of disagreement and within 10 days of resuming talks, on July 25th, 1963, the three nations reached agreement on the treaty. The next challenge was getting the U.S. Senate to ratify the treaty, a task that at first seemed impossible due to the prevailing Cold War mentality of the Senators, and the fact that a 2/3rds majority was required. Over the next 7 weeks, however, JFK, with the help of Norman Cousins and a group of government officials and private citizens, conducted an intensive lobbying effort that turned the tide; and on September 24th, 1963, by a vote of 80 to 19, far more than the required 2/3rds, the Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty. The “impossible” had been accomplished.

I can’t prove it, but my personal belief is that without Pope John and his historic work Pacem in terris, there would have been no Kennedy “Peace Speech” at American University, and there would have been no Limited Test Ban Treaty. I believe that the Pope’s words had a major impact on JFK, who was himself, Catholic; and I believe that they affected Khrushchev as well. When one reads Pope John’s words for himself one is left to wonder, how could they not?

Much of what follows is quoted directly from Pacem in terris. Addressed to “All men of good will”, it was the first Papal encyclical that intended a larger audience than Catholics. The text of the encyclical then commences as follows:

“Peace on Earth—which man throughout the ages has so longed for and sought after—can never be established, never guaranteed, except by the diligent observance of the divinely established order…”

It then goes on to describe this “divinely established order” as the work of God and that it is perfect in its creation. And yet, Pope John states:

“…there is a disunity among individuals and among nations which is in striking contrast to this perfect order in the universe. One would think that the relationships that bind men together could only be governed by force.”

As he progresses through the message of the encyclical Pope John emphasizes that world peace can only be accomplished by adherence to the “divine order” as manifested within each individual person; thus, a huge part of his encyclical deals with the subject of human rights, at times sounding not unlike the founding documents of the United States. The Pope introduces this section of “Pacem in terris” as follows:

“We must devote our attention first of all to that order which should prevail among men … Any well-regulated and productive association of men in society demands the acceptance of one fundamental principle: that each individual man is truly a person. His is a nature that is endowed with intelligence and free will. As such he has rights and duties, which together flow as a direct consequence from his nature. These rights and duties are universal and inviolable, and therefore altogether inalienable.”

The encyclical then goes on to enumerate these rights, reading much like the “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” passed by the United Nations in 1948. Indeed, later in the encyclical the Pope makes special mention of this document:

“A clear proof of the farsightedness of this organization (the UN) is provided by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights passed by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948. The preamble of this declaration affirms that the genuine recognition and complete observance of all the rights and freedoms outlined in the declaration is a goal to be sought by all peoples and all nations.”

As regards the natural duties of each individual person, derived from the same natural law as their rights, the Pope states:

“The natural rights of which we have so far been speaking are inextricably bound up with as many duties, all applying to one and the same person. These rights and duties derive their origin, their sustenance, and their indestructibility from the natural law, which in conferring the one imposes the other.”

It is clear from Pope John’s “Pacem in terris” that he felt bringing about peace on our planet would require an adherence to these natural rights and duties by governments and men, and that a real peace could not be attained without this. As stated by Pope John:

“The common good of individual States is something that cannot be determined without reference to the human person, and the same is true of the common good of all States taken together. Hence the public authority of the world community must likewise have as its special aim the recognition, respect, safeguarding and promotion of the rights of the human person.”

“Pacem in terris” makes the point that to arrive at the level of mutual trust necessary between nations to attain peace, people and their nations would first have to arrive at this recognition of the fundamental nature of man and his inherent rights. The encyclical then challenges the world’s people and leaders to do just that…stated as follows:

“Hence among the very serious obligations incumbent upon men of high principles, we must include the task of establishing new relationships in human society, under the mastery and guidance of truth, justice, charity and freedom—relations between individual citizens, between citizens and their respective States, between States, and finally between individuals, families, intermediate associations and States on the one hand, and the world community on the other. There is surely no one who will not consider this a most exalted task, for it is one which is able to bring about true peace in accordance with divinely established order.”

Of such is the document, “Pacem in Terris,” by Pope John XXIII, published on April 11, 1963.

As noted above, Pope John passed away on June 3rd, 1963, and a week later JFK delivered his “Peace Speech” at American University. That Kennedy understood the point of Pope John’s words is evident by his own words, spoken in his famous speech:

“All this is not unrelated to world peace,” Kennedy said. “‘When a man’s ways please the Lord,’ the Scriptures tell us, ‘he maketh even his enemies to be at peace with him.’ And is not peace, in the last analysis, basically a matter of human rights—the right to live out our lives without fear of devastation—the right to breathe air as nature provided it—the right of future generations to a healthy existence?”

Without the influence of Pacem in terris, I don’t think Kennedy speaks those words, and I don’t think the Limited Test Ban Treaty that followed would have happened.

Thus, we, today, have our legacy, and it is clear. Martin Luther King, John Kennedy, Pope John and even Nikita Khrushchev are all gone now. So are Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, John Locke [12] and, going earlier, Thomas Acquinas and St. Augustine. Their words, however, live on, and we must let them speak to us; for in them is the universal truth, probably best summated by Pope John in his great work:

“Any well-regulated and productive association of men in society demands the acceptance of one fundamental principle: that each individual man is truly a person. His is a nature that is endowed with intelligence and free will. As such he has rights and duties, which together flow as a direct consequence from his nature. These rights and duties are universal and inviolable, and therefore altogether inalienable.”

The duty of carrying this truth forward now falls to us, and in this task we must not fail; for if we do, the dream of a world at peace—real peace—will remain just that—an unrealized dream.

Copyright © 2018

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

____________________________________

[1] Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, (1954),was a landmark U.S. Supreme Court case in which the Court declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the unanimous (9–0) decision stated that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” As a result, racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution. This ruling paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the Civil Rights Movement.

[2] Saint Augustine (354 AD-430 AD) was an early Christian theologian and philosopher who was one of the major fathers of the early Christian Church. One of the most prolific writers of the early Church, his work was instrumental in the development of Western Christianity and Philosophy. Augustine’s ideas had a vast effect on Martin Luther, thus many Protestants and Lutherans consider him to be one of the theological fathers of the Protestant Reformation.

[3] Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274 AD) was an extremely influential Catholic priest, philosopher, jurist and theologian whose ideas are still studied and used extensively, both within the Church and without. He was the leading proponent of what is termed “natural theology”, which basically argues that the existence of God is best demonstrated by logic and the ordinary experience of nature.

[4] Martin Buber (1878-1965) was a Jewish existentialist philosopher widely renowned for his book “I and Thou” (1923) which presents a philosophy of personal dialogue, in that it describes how personal dialogue can define the nature of reality. Buber’s major theme is that human existence may be defined by the way in which we engage in dialogue with each other, with the world, and with God. According to Buber, human beings may adopt two attitudes toward the world: I-Thou or I-It. I-Thou is a relation of subject-to-subject, while I-It is a relation of subject-to-object. In the I-Thou relationship, human beings are aware of each other as having a unity of being. In the I-Thou relationship, human beings do not perceive each other as consisting of specific, isolated qualities, but engage in a dialogue involving each other’s whole being. In the I-It relationship, on the other hand, human beings perceive each other as consisting of specific, isolated qualities, and view themselves as part of a world which consists of things. I-Thou is a relationship of mutuality and reciprocity, while I-It is a relationship of separateness and detachment.

[5] Mahatma Gandhi (born Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, 1869-1948) was the primary leader of India’s independence movement against British rule, and also the architect of a form of non-violent civil disobedience that would have a vast influence on the world, including specifically on U.S. Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King and South Africa’s Nelson Mandela. Gandhi trained to be an attorney in London from 1888-91, and prior to leading the Indian nationalist movement was a major civil rights leader in South Africa up until 1913, when he returned to India. Himself a Hindu, as Gandhi got older and became more famous he became known as “Mahatma”, which means “great soul,” and was known for promoting religious tolerance between India’s major religions, Hinduism and Islam. After decades leading the nationalist movement in India, Gandhi’s country gained its independence at last in 1947. A few months later, at the age of 78, he was assassinated by a Hindu extremist.

[6] Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was an English-born political philosopher and writer who supported revolutionary causes in America and Europe. Published in 1776 to international acclaim, his Common Sense was the first pamphlet to advocate American independence. After writing the The American Crisis papers during the Revolutionary War, Paine returned to Europe and offered a stirring defense of the French Revolution with Rights of Man. His political views led to a stint in prison; after his release, he produced his last great essay, The Age of Reason, a controversial critique of institutionalized religion and Christian theology. Paine wrote Rights of Man in 1791 as a response to a critique of the French Revolution by Anglo-Irish statesman Edmund Burke. In it Paine stridently defended the right of a people to revolt when a government does not safeguard their natural rights.

[7] King John’s Magna Carta guaranteed to all free men immunity from illegal imprisonment, a guarantee that has traditionally been invoked by way of the writ of habeas corpus. Under the concept of habeas corpus in Anglo-American jurisprudence, persons who are deprived of their liberty have the right to challenge the legality of their arrest or detention through a judicial inquiry. Habeas corpus is a Latin phrase meaning “produce the body.” By means of the writ of habeas corpus a court may order the state to “produce the body,” or hand over a prisoner so that it might review the legality of the prisoner’s detention.

[8] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a milestone document in the history of human rights. Drafted by representatives with different legal and cultural backgrounds from all regions of the world, the Declaration was proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 as a common standard of achievements for all peoples and all nations. It sets out, for the first time, fundamental human rights to be universally protected and it has been translated into over 500 languages.

[9] An encyclical is a papal letter sent to all bishops of the Roman Catholic Church, or to all the bishops within one country. Thus, you can see how unusual it was for Pope John to address “Pacem in terris” to “All men of good will.”

[10] Nikita Khrushchev (1894-1971) led the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War, serving as Premier from 1958 to 1964 and as first secretary of the Soviet Communist Party from 1953-1964. Though he largely pursued a policy of peaceful coexistence with the West, he also played a major role in instigating the Cuban Missile Crisis by placing nuclear weapons in Cuba, 90 miles from Florida. At home, he initiated a process of “de-Stalinization” that made Soviet society less repressive and a bit more liberal; and also oversaw the developing Soviet space program. With the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis in late 1962 he, along with President Kennedy, took definite steps across the next few months toward resolving the problems between the Soviet Union and the United States, as described in this article, which ultimately resulted in the Limited Test Ban Treaty. In October, 1964, not quite a year after the assassination of JFK, Nikita Khrushchev was deposed from power and replaced by Leonid Brezhnev. Without Kennedy and Khrushchev their two countries slipped back into the prior Cold War pattern which would continue for another generation until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

[11]Norman Cousins (1915-1990) was an American journalist, author, professor and ardent supporter of world peace and nuclear disarmament. From 1942-1972 he was the editor in chief of the magazine Saturday Review and under his watch its circulation expanded dramatically, from around 20,000 to over 600,000. In the 1950s, observing the threat of the arms race, he became chairman of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy (SANE) which warned that in continuing the arms race the major powers were charting a course to disaster. He also wrote a number of articles and books promoting disarmament and world peace. His prominence as a journalist and anti-nuclear peace advocate were likely the major reasons he was selected by Pope John XXIII to be his emissary to and between Khrushchev and JFK. He wrote a book, The Improbable Triumvirate, about his experiences during his missions on behalf of the Pope to Khrushchev and Kennedy which is well worth the read, though a bit hard to find. Later in his life, due to his own experiences with severe illness, Cousins conducted research into the effect a positive attitude, optimism and just plain laughter had on illness and wrote a book on the subject. Norman Cousins died of heart failure in 1990. He was 75 years old.

[12] John Locke (1632-1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. (also called the Age of Reason, and extending from the mid 1600s to the late 1700s, the ideas of the Enlightenment undermined the authority of the monarchy and the Church and paved the way for the political revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries.) Considered one of the first of the British empiricists (simply stated Empiricism is the theory that human knowledge is derived primarily from observation and perception), his work greatly affected the development of epistemology and political philosophy. Locke’s writings influenced Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, many Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, as well as the American revolutionaries. His contributions to classical republicanism and liberal theory are reflected in the United States Declaration of Independence.

6 Responses

Cogent , rigorous and relevant to the challenges of our time . Should be required reading in every high school and college in this country.

Thanks Roger! As you know, we have much to do…See you soon. MA

The dilemma for our time is that any argument for natural rights and thereby human rights are circular arguments. The only way to avoid this circular argument is to affirm that rights for human beings extend from a spiritual nature and not from the material nature of humans in the material universe. That spiritual presupposition has to be maintained and defended or else any human rights can, and eventually will, be compromised by the demands for expedient solutions to problems. Keep the faith.

Thanks, John. I was struck by the fact that so many of the philosophers and activists along the line of Human Rights/Natural law were deeply religious people, which of course is exactly the point you are making. Keeping the faith here in Seattle…L Mark

Very enlightenig,thank so mich!!!

You’re welcome, Sylvia! I appreciate your interest and acknowledgement. Best, Mark