Preface: Jim Haffner is a friend of mine, but as with many friends in these hectic lives we live, we’ve never really had much chance to talk. When we do get to spend 5 or 10 minutes over lunch or coffee or whatever, we rarely get past what’s happening with the Mariners or the Seahawks; which is OK I guess, since we are both fans, but you don’t really get to know someone that way. One day, not too long ago, that all changed for Jim and I. He had forgotten something at home and I had some time on my hands, so I offered him a ride. What with him living in Everett some 30 miles north, and the state of Seattle traffic these days, we had nearly an hour to kill during the car ride. Now, Jim and I are the same age, in our mid 60s; and both baby boomers who grew up in the Seattle area, so our talk reflected this. We spoke of our experiences in the late sixties and early seventies, of the drugs we took, and the music we listened to, and the Vietnam War; the avoidance of which was the central dilemma for many young men of our generation. Our talk of war inevitably led to the fact that both of our fathers had served honorably in World War II, Jim’s dad in Europe and mine in the South Pacific. It was then that Jim relayed to me the tale of his father’s wartime experience, and for the next 15 minutes, as I drove through the traffic, I listened in rapt attention; for the World War II story of Jim Haffner’s dad is nothing short of incredible. I resolved then and there to make his story known—and here it is…MA

Dedicated to the 405,000 American Servicemen Who Didn’t Come Home from World War II

According to his own words,[1] James Daniel Haffner was born during a blizzard at around 11pm on the night of April 3rd, 1920 in the small town of Sigourney, Iowa. Due to the fact that the town doctor was snowed in and could not be in attendance, the honor of pulling him into this world fell to his father. His parents, a brother born 4 years earlier, a sister born 2 years later, and Dan himself (the Haffner family to this day have a loose tradition of being called by their middle names—my friend Jim included) comprised the family of 5 that moved to Seattle in 1925, settling in the Green Lake area. It was there that Dan grew into a young man with a passion for sports, particularly baseball; but also one who, by his own admission, lacked “a great deal in the way of academic credentials.” He graduated from Seattle’s Lincoln High School in 1938 and across the next 3 years, while apprenticing with his father, launched a career as a journeyman painter. On Sunday, December 7th, 1941, Dan was just about to start a game of touch football with his friends at Woodland Park close to Green Lake, when they heard the news on the radio that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. The next day, like thousands of young men all over the country, Dan went to the downtown Seattle recruiting office intending to join the Army Air Corp to become a fighter pilot; but after discovering it required 2 years of college as a prerequisite, he settled instead for signing into the Air Corp as an enlisted man. Thus began the World War II story of James Daniel Haffner.

Dan did his Boot Camp at a place called Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, where he says, “we learned to march, we got shots, and took aptitude tests.” From there he was sent to Rantoul, Illinois to be trained as a flight mechanic. Half way through the flight mechanics course the Army announced it was waiving the 2 year college requirement rule for pilot training if the applicant could pass the same exam as the collegiate candidates. His lack of academic credentials notwithstanding, Dan was one of the 8 or so men who passed from the 500 at Rantoul who took the exam, and soon was on his way to the Army Air Forces West Coast Training Center in Santa Ana, California. He would have his shot at becoming a fighter pilot!!

After completing his ground training there in Santa Ana, Dan was sent to the town of Tulare a couple hundred miles north of Los Angeles for his flight training. In Dan’s words the training in Tulare, “…wasn’t so easy. Landings and takeoffs were difficult in the backseat of a two-seater. Time was ‘of the essence’: You were allowed 12 hours in which to become proficient enough to solo or (you were) out! My instructor thought I was ready, so we went to a nearby field to shoot a practice landing. He was going to exit and me (fly) solo.”

Alas, Dan’s landing was considered bad because he had to circle twice to successfully bring the plane to the ground, and as a result he had to take his “cracked ego and bent dreams” back to Santa Ana to prepare for Bombardier school. He completed this training, receiving his wings and 2nd lieutenant bars at Roswell, New Mexico on February 13th, 1943. From there he was sent to several other small towns throughout the West, ultimately arriving at Lewiston, Montana where he and his crew did their combat training. Special training on the famous Boeing built B-17G bomber, the plane that Dan and his team would be flying on their bombing missions in Europe, then took place in Orlando, Florida; following which it was back to Lewiston where the rest of their squadron was filled out. The B-17 manned by Dan and his fellow crewmen was christened “Omar the Dentmaker” and was assigned to the 615th squadron of the 401st Bomb Group, Colonel Bill Seawell commanding.

Meanwhile, as all of this training was going on, a war was happening. Personally I don’t think all of the training in the world can prepare one for the blood and carnage that is real war; and World War II, which devastated all of Europe, much of North Africa, the South Pacific and Asia, while claiming in excess of 60 million lives, took that blood and carnage to a scale never before seen on planet Earth. As the year of 1943 was winding down, that was the war that James Daniel Haffner was about to enter for real.

In December of 1943, “Omar the Dentmaker”, Dan and the rest of the crew arrived in England at an airfield called Deneethorpe [2], which was located north of London. There they spent the next month learning tactics. At this point in the war, though the Russian Red Army had succeeded in halting the German advance into their country and had started to turn the tide on the Eastern front, all of Western Europe was still under the NAZI jackboot. The planned Allied invasion at Normandy (D-Day) on the northern coast of France was still 6 months into the future, and the war was anything but won. By late January, 1944, and on into February, Dan and his mates were flying their B-17 on fighter escorted bombing missions into France and Germany on a regular basis, hitting the German cities and suburbs of Berlin and Kiel to get the factories and port facilities; and the Pas-de-Calais region of northern France to take out the German V-1 rocket launch sites that were terrorizing London. According to Dan the B-17 crews called the fighters accompanying them their “protectors”, and he states that they “often made the difference in whether the bombers ever made it to their assigned targets or went down in flames, forever.” On one occasion they flew an especially tough mission to bomb the port of Bordeaux in southern France. It was a flight that made an indelible impression on Dan, and he describes it as follows:

“The long mission to Bordeaux (9 hours) was particularly memorable. We had flak [3] and fighters all the way, and we could see our planes going down in flames constantly. With great weariness, after dropping our bombs and re-forming our three Wings into one, we struggled home with terrible losses.”

And so it went for Dan Haffner and the crew of “Omar the Dentmaker”. Across the closing weeks of February, 1944 and on into March, mission after mission was carried out, always with the possibility of a terrible death tugging at their sleeve. One can imagine how it must have been for those fliers; when after every mission they would see more empty chairs at the mess halls where just the day before they sat with their friends, talking and telling jokes. Those same empty chairs must have been a constant reminder to them, that their next mission could well be their last; and the damnable thing was that there was little they could do about it—if their number came up, then their number came up. Under those circumstances, if they developed a fatalistic attitude it was forgivable, and certainly understandable.

Ironically for Dan Haffner and the rest of his crew, the mission that ended in disaster for them started out easy and was expected to be a relatively quick run with little or no opposition. On Sunday morning, March 26, 1944 they were called to an early briefing and given their orders. The target was the V-1 rocket launch sites in Pas de Calais, just across the channel from England in northern France. As they arrived at their target and directed their B-17 into its bombing run everything to that point had gone perfectly. There were no German fighters to be seen, and there was no flak—a relative cakewalk—and then abruptly it all changed. Dan himself describes what happened next:

“A shell exploded suddenly inside our plane behind the pilot. A single burst of flak had hit us squarely. We immediately went out of control and according to eyewitnesses from planes I talked to later, we flew upside down and backwards through the formation, causing other pilots to frantically dodge out of our way. The plane began to disintegrate, wings, engines etc. breaking off.”

The situation that Dan and the crew of “Omar the Dentmaker” found themselves in was a worst case scenario. Their plane was falling apart, and any of them who weren’t killed instantly by the explosion had little chance of successfully bailing out. In the nose compartment, where Dan was stationed as bombardier, guns and equipment were flying loose. Centrifugal force made it impossible to control one’s own body and movements. To make matters worse, he wasn’t even wearing a parachute, having removed it to concentrate on the bombsite. Through the confusion Dan caught a glimpse of his friend and navigator, Mike Walsh, who was behind him, close to the nose compartment escape hatch. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a parachute bounced into Dan’s arms and he clutched it like he would a football; it later occurring to him that perhaps Mike had tossed it towards him. Just then the nose of the plane sheared off, and Dan found himself sliding into the now gaping opening. Within a split second he was clear of the wreckage and plummeting towards earth.

Even after reading his account, how James Daniel Haffner lived to tell the tale of his last bombing mission of the war I still have no idea. I have heard it said of some men, that when faced with the threat of imminent death they entered a mental state characterized by extreme clarity of thought and action. Based on Dan’s description of the next few moments, I think he must have been one of those men:

“I hit the air with such force that my boots were ripped off my feet and I fell, tumbling wildly, clinging to the parachute pack…After some seconds the fall became more orderly with the feet and head skyward and the bottom down. Then I began to hook on my chest (parachute) pack, first one side, then after looking earthward to see if there was still time, hooking the other side. We were taught to wait as long as possible to pull the rip cord, thus enhancing our chances to avoid being seen…but Earth was pretty close by this time, so I pulled, made a good landing, tumbling over a few times, then gathered up the chute and buried it as we were taught to do.”

Dan was now safe on the ground and, miraculously, he was uninjured. He didn’t know the fate of his fellow crewmen, but having seen no other chutes as he descended, he feared the worst. He started to walk casually towards some woods he spied a distance away, but on seeing soldiers emerge from the woods and head towards him he changed paths and started walking towards some boxcars a few hundred yards off; only to see more soldiers head his way from that direction. Surrounded, he was captured by the Germans in short order. For James Daniel Haffner the war was over, and he would sit out its remainder in a German prisoner of war camp.

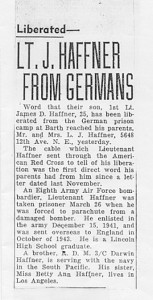

As it turned out another of Dan’s fellow crewmen had survived the disintegration of “Omar the Dentmaker”[4]; a man named John B. Carson, who was the tail gunner on the doomed B-17. He also was captured, and after interrogation both men were packed into a freezing box car with 68 others and shipped to the village of Barth, Germany, about 100 miles north of Berlin on the Baltic Sea. There they were incarcerated in a POW camp called “Stalag Luft I” [5] along with over 7,000 other English and American airmen. Both men spent more than a year there, until the camp’s liberation by the Russian Red Army on May 1st, 1945. From what I could find neither man spoke much of their experiences while imprisoned.

At last freed from captivity, Dan was evacuated from Germany on a US 8th Air Force plane on May 5, 1945 and flown to a holding camp in France. From there a few days later he was flown back to Deenethorpe in England where he rested and waited for two months to go home. Obviously eager to once again see his family and friends, shortly after leaving Germany Dan penned them a letter expressing his feelings:

“…I cannot explain in words how wonderful it is to be free again and in the friendly and protecting hands of Uncle Sam. I hope that I will find you all well and happy when I get home and that the last year and a half has not caused you too much anxiety. Everything is being done to get us home as quickly as possible, so please be patient for a little while longer. Your Loving Son, Dan”

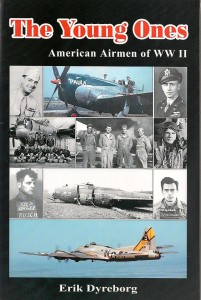

Later, when Dan had actually arrived back in Seattle and saw his folks again, one gets a sense of how he felt from the words he wrote about his homecoming as included in the book, “The Young Ones—American Airmen of WW II”. His sentiments as expressed are simple and direct:

“Hurrah for the Good Old U.S.A…it’s good to be HOME AGAIN!!!”

World War II was over. James Daniel Haffner would go on with his life, have a career, get married, and have children of his own; one of whom I would eventually meet and count as a friend. I will wager, however, that of all the days he lived—from that fateful day in March of 1944 in the skies over France, to the day of his death in 1996—that there was not one of those days that he did not think of his 8 lost compatriots, his fellow crew of “Omar the Dentmaker”. Perhaps he wondered what they would be doing now, had they survived that day; or why it was that he was spared and they were taken. Or perhaps, if he was wise, he had faith that they would all meet again one day; to share their stories, and to reminisce—for that is the way of the old soldier, and the crew of “Omar the Dentmaker” would certainly have a lot to talk about.

THE END

Except for quoted material

Copyright © 2016

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] James Daniel Haffner’s own account of his World War II experiences can be found in a book entitled “The Young Ones—American Airmen of WW II”, by Erik Dyreborg. A cover image of the book is included in this article.

[2] Constructed in 1943 and opened for use in October of that year, the Deneethorpe field was specifically constructed to accommodate the Boeing built B-17 bomber and was assigned to the US Army 8th Air Force for use. The 401st Bomb Group, which included the 615th squadron, to which Dan Haffner belonged, started arriving there for duty in November of 1943.

[3] The exploding shells of anti-aircraft fire are called “flak”

[4] The bodies of the other 8 men in Dan’s crew were found by French villagers strewn across about 1,000 yards of ground outside of the town of Bouquemaison in the Pas de Calais region of northern France. As directed by the Germans, the villagers buried them in their town cemetery. Later the US military exhumed the bodies and re-buried them with full military honors.

[5] “Stalag” is a German term used to designate prisoner of war camps. “Luft” is German for “air” and was used to designate stalags run by the Luftwaffe (the German Air Force) specifically for captured allied airmen.

14 Responses

Appreciating the time and energy you put into your

blog and detailed information you offer. It’s good to come across a blog

every once in a while that isn’t the same out of date rehashed information.

Great read! I’ve bookmarked your site and I’m adding your RSS feeds to

my Google account.

Thank you for putting my Grandpa’s story in to such beautiful words. I’m proud to carry the Haffner name.

You are so welcome Lisa! You and the entire Haffner family can be justly proud of your Grandfather and his inspiring story…Your Friend, Mark

Wow. I have wanted to know the story about my Uncle Dan ever since I was a little girl and saw his picture with his crew and airplane.Thanks so much for posting this story. I got to this site by looking up Jim and got to read it. I am his sister Betty Haffner’s daughter, Pam.

You’re Welcome, Pam! It has been my pleasure and honor to write and post your Grandfather’s story. I was incredibly moved by it. Feel free to share with whomever you wish. Your Friend, Mark

Hello Mark, thank you for sharing this incredible story. My uncle was the waist gunner on Omar the Dentmaker. His name was S/Sgt Frank A Rothwell. Sadly he died in the crash. He and the rest of his crew that perished were buried (like you said) in a tiny cemetery in Bouquemaison by a gentleman named Monsier Jacquemelle-Lefebvre. They were the only Americans in it. He later said he cared for their graves as he did his own parents.

Most of them ended up in an American military cemetery in Normandy in 1946.

I have been trying to get as much information about my uncle and his crew and I would love to be able to email you if that’s ok. My email is nhlrox88@comcast.net.

Thank you again!

-Josh

I forgot to mention, my Uncle Frank is in the top row, third from the left on the picture of the crew!

Hello Josh!

So nice to hear from you. The story of your uncle, Mr. Haffner and the others is unique and remarkable and it has been my pleasure and honor to write and post about it. Please feel free to e-mail me at mark@fromanativeson.com

I look forward to hearing from you.

My Best,

Mark Arnold

Thanks, Mark, for providing me a vivid memory on this day designated to such brave, honorable American military folks. Mostly in tears as I read this today. Thanks for sharing it; I’ve not read it before. My uncle was also a prisoner of war at that time. He was so happy to return to the U S of A. At my daily job, I get to speak to some of these WWII folks on the phone a lot. They are truly heroic and very stoic individuals, deserving our admiration for eternity!

Thanks, Joline! So happy you enjoyed the story and I am glad you are there to help the vets. They deserve it. L MA

Thanks so much Mark! I always appreciate the details and references you dig up! For those of us born in the 60s, most think that maybe we can’t really relate. But if we have a good memory – We can also remember being there or in situations like this so this hits home to so many of us, Looking forward to more!

Thanks, Shanta! You’re welcome for the articles. I love history taken down to the personal level, such as Jim Haffner’s dad’s story. More coming soon. L, M

I’m working on a documentary about a US POW who was held at Stalag VIIa. Are the photos on this site PD, or if you own them, what is your policy regarding use of them in a film? For now, it’s non commercial, but that could change in the future. Thanks!.

jmm in STL

Hi Jim,

I don’t own the photos. Some were provided to me by family members, some of the photos I pulled from on line, while others came from the book referenced in the post, “The Young Ones.” You should check that book out and query the authors about the use of photos if you have questions. Good Luck with your project! Best, Mark