Note: Between 1989 and 2003 the West African nation of Liberia was nearly destroyed by almost 14 years of continuous civil war during which 250,000 people died, human rights violations became rampant and over 1 million people were forced from their homes. To understand and make known how and why this humanitarian disaster could have occurred I have researched and written this article entitled “Human Rights at the Crossroads: A Short History of Liberia”. Due to its length the article is presented in two parts. Part I covers the history of Liberia from its birth as a nation in the early 1800’s to the mid 1980s (right before the onset of the civil war) . Part II, presented here, deals with the civil war years on up to present time and the efforts underway currently in Liberia to bring about full awareness of human rights and their importance, so that such a disaster can never occur again. To get the full understanding and context of what happened in Liberia Part I of the article should be read first and can be found in this blogsite. ( http://fromanativeson.com/2015/04/26/human-rights-at-the-crossroads-a-short-history-of-liberia-part-i-by-mark-arnold/) With that understood, here is “Human Rights at the Crossroads: A Short History of Liberia Part II:

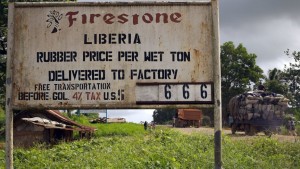

In January of 1986 Samuel Doe took the oath of office as president of Liberia; the first president of what Doe, in recognition of the country’s new constitution and the fact that he was the nation’s first ever indigenous African president, called the “Second Republic of Liberia”. However, with the fraudulent election, his favoritism toward his Krahn people and his ethnic reprisals in the wake of the November, 1985 coup attempt, Doe had made enemies. In response to this, across the late 1980’s his regime became even more repressive with his government troops massacring thousands of rival tribal Africans. As long as he retained the favor and aid of the United States Doe’s government was more or less impregnable; but with the Reagan administration coming to an end in the US in early 1989, the Cold War winding down, and increased corruption in the Liberian government, the United States began to curtail its aid to the west African nation. By 1989 the ensuing economic hardship, which at one point prompted Doe to ask Firestone for an advance on its future taxes, and the upset caused by his repressive policies had put Doe and his government in a very dangerous position. Factor in Liberia’s long history of ethnic and economic suppression of the majority of its own people and one can see that an explosive situation existed in the country, ripe for civil war. All that remained was for someone to come along and light the fuse. It was at that point, as if on cue, that Charles Taylor returned to Liberia.

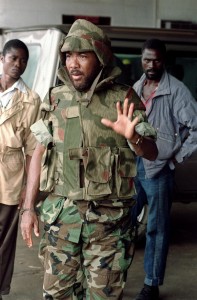

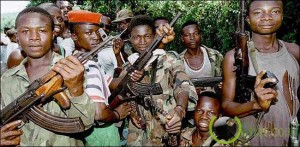

On Christmas Eve of 1989 Taylor and a few dozen of his followers quietly crossed into Liberia from the neighboring country of République de Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) and launched their rebellion against the Doe government. Due to their small numbers and limited resources Taylor’s rebellion didn’t appear to be much of a threat; but Doe’s savage response, with his troops ruthlessly murdering innocent civilians, succeeded in rallying thousands of Liberians to Taylor’s movement, which by now he was calling the “National Patriotic Front of Liberia” (NPFL). Among these recruits were a number of children and adolescents who formed what was known in Taylor’s army as “The Small Boy’s Unit.” Entry to the “Unit” often required acts of violence and killing by the prospective recruits, who swore their allegiance to “Papai,” as Taylor was called by them. Before too long this “Small Boy’s Unit” become notorious for their viciousness and killing.

As the civil war expanded across the first few months of 1990 Taylor’ reputation grew and he became something of a legendary figure in Liberia. He portrayed himself as a Baptist minister intent on bringing democracy to the country and ridding it of oppression. When he spoke to groups he often wore flowing white linen and by all accounts could mesmerize a crowd. To the indigenous, tribal Africans, many of whom retained a strong spiritual reality, as the successes of his army mounted Taylor took on a mystical air. By April of 1990 he and his army controlled much of the interior of Liberia and by June he was ready to move on the Firestone rubber plantation, just 40 miles from the capital of Monrovia. The fighting to that point had been especially violent, particularly on non combatants. If suspected of government collaboration they would be raped or massacred by Taylor’s forces and if suspected of abetting the rebels would be subject to the same from government troops. For most Liberians, as the violence intensified loyalties blurred, and the slaughter became indiscriminate.

In mid June of 1990, with Firestone executives and staff leaving their African employees to their fate and fleeing the country, Taylor took the Firestone plantation and was soon attacking Monrovia. In July a faction of Taylor’s army, led by a man named Prince Yormie Johnson, split from the NPFL and carried on the attack as the INPFL (Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia). Defending Monrovia against both groups were Doe’s government troops, the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL). Johnson’s troops quickly took several districts of Monrovia, forcing the evacuation of foreign citizens and diplomatic personnel by the US Navy, which in turn prompted the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) [1] to decide to send a several thousand man peace keeping force to Monrovia. With the peace keepers yet to arrive and Taylor’s and Johnson’s forces closing in, the ECOWAS tried to persuade Doe to leave the country, but he refused. Thus, in early September of 1990, while making a visit to the Monrovian headquarters of the still not fully arrived ECOWAS peace keepers, Doe was captured by some of Johnson’s troops and, after being tortured, was brutally killed. With Doe out of the way Johnson’s INPFL and Taylor’s NPFL then vied for control of the Liberian capital with much bloodshed resulting in the city and surrounding areas.

In November the ECOWAS peace keeping force (called ECOMOG for Economic Community Monitoring Group) fully arrived and succeeded in getting Taylor and Johnson to agree to their intervention. Nevertheless violence still flared from time to time and never really stopped. Continued efforts at stemming the fighting resulted in an interim government (called the Interim Government for National Unity, or IGNU) being formed that was protected by the ECOMOG peace keepers. This government, by early 1991, was able to establish control over most of Monrovia. Taylor did not recognize the government, however, and his NPFL controlled most of the Liberian countryside outside Monrovia (the NPFL held territory was popularly dubbed “Taylorland” by Liberians). Any territory Taylor did not control fell to Johnson’s INPFL or to gangs of ruffians. Across the balance of 1991 a number of attempts to broker a peace took place in neighboring West African capitals but none of them really succeeded.

By early 1992 the interim Liberian government (IGNU) had succeeded in gaining the support of Johnson’s INPFL, but not Taylor’s NPFL. Instead Taylor was busy consummating a deal with Firestone that would allow the American rubber giant to resume operations. According to the deal Firestone’s taxes and payments, formerly paid to the Liberian government, would be paid to Taylor and his group. It was a deal that would come back to haunt Firestone with accusations that it ignored the human rights abuses, rapes and murders of Taylor’s NPFL fighters in favor of its own profits. As a result, by August of 1992 the Firestone plantation, which had been out of production for nearly two years due to the civil war, was back in business, producing 600,000 lbs of rubber in that month and over 3 million lbs in September. As part of the deal Taylor also provided troops to protect the plantation. The money he got in exchange helped him fund his operations, which in August and September of 1992 included preparing for what would be his plan to take control of Monrovia and Liberia once and for all—an operation that Taylor would call “Octopus.”

Using the Firestone plantation as a planning and staging base for the operation, by October Taylor was ready to launch Octopus on Monrovia. The plan called for the full strength of Taylor’s NPFL army to attack the city from multiple directions, enveloping it like an octopus would its prey, hence the operation’s name. The attack came at 3 AM on October 15th, 1992, with a sustained mortar and artillery barrage of the city as Taylor’s forces advanced on the capital from the north and east. Their goal was to take the Monrovian suburbs and the only remaining airport available to the interim government. At the same time another rebel faction allied to the NPFL attacked from the west to take the Monrovian port. With the Atlantic Ocean at its back and the city otherwise surrounded, the interim government officials, the ECOMOG peace keepers and the Monrovian people had nowhere to turn. Taylor and his generals predicted the city would fall in two weeks.

The fighting during the first few days of Octopus was especially violent. As Taylor’s troops, who often were not more than children or adolescents, advanced through Monrovia’s neighborhoods they carried out summary executions of anyone suspected of supporting or collaborating with the interim government; as well as anyone thought to be part of the Krahn tribe (Doe’s people) or other ethnic groups that had supported Doe. Over 200,000 people from outlying areas descended on Monrovia to escape the madness, creating a desperate situation in the city. Hunger and looting were rampant and bodies were left where they fell, rotting in the streets. People crouched in their homes hoping to avoid the slaughter, but often died there as well. Hell has been described as the complete absence of reason, and that description of Monrovia during this time, by all the accounts I have discovered, is especially apt.

After the first few days of fighting Taylor’s perimeter around Monrovia had shrunk to two miles and closing. Within were packed the interim government, the ECOMOG forces and several hundred thousand non combatant citizens. Officials at the American embassy, fearing that Taylor’s army would soon overrun them, started evacuating their non essential personnel and made preparations for quick escape, should it be necessary. When things appeared to be at their worst, however, the West African peace keepers were able to mount a counter attack that prevented Taylor from completely taking the city. Using bombardment from Nigerian naval vessels and bombs from Nigerian planes they were able to push Taylor’s forces back to the suburbs, and for the next few weeks the battle lines moved back and forth across the Monrovian neighborhoods as the casualties mounted.

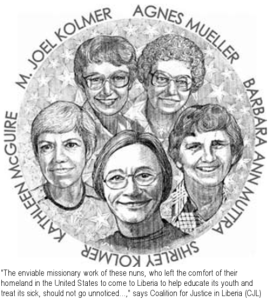

A week or so into Octopus an unusually grievous incident occurred that finally drew the attention of the United States and the world to the humanitarian situation in Liberia. It should not have required something like this, for in truth there is nothing intrinsic about one life that necessarily makes it more important than any other; something I am sure that the victims in this instance—five American Catholic nuns—would have agreed with. In fighting that took place on the night of October 23rd the the nuns’ convent was cut off from government troops as the battle raged back and forth. The US embassy was informed that two sisters were missing and the ambassador pressured the West African peace keepers to mount an effort to find and rescue them. The peace keepers tried but had to withdraw after meeting stiff resistance. Weeks later the two missing sisters were found dead in a car, while the bodies of the other three were found in the convent itself. All five had been murdered. Taylor, though he did not pull the trigger, was universally held responsible for the killings. The US State Dept called the murders a “cowardly act” and said that the US was “shocked and appalled” by them. Pope Paul II termed the nuns “martyrs” who had been “brutally murdered.”

Unfortunately the increased international attention that resulted from the murder of the nuns had no immediate effect on the violence in Liberia, which continued unabated. Operation Octopus convulsed on until late December but Taylor never succeeded in taking Monrovia and he and his forces ultimately withdrew to areas outside the city. Across the next several years the civil war continued with various peace agreements taking place that would temporarily bring a relative calm, only to have it shattered by more eruptions of violence. In mid 1994 the hostility became especially intense and the humanitarian situation in Liberia perhaps reached its zenith, with over 1.8 million Liberians needing urgent assistance in the form of basic necessities like food, water and shelter. Due to the insecure and violent situation, however, humanitarian agencies often could not get through to the people, and the deaths mounted into the hundreds of thousands as a result.

Another peace was brokered in August of 1995 that called for elections to take place in 1996 to at last provide an elected government for Liberia. Before the elections could occur, however, violence broke out again in April of 1996 which led to the evacuation of most international organizations from Monrovia and the destruction of much of what was left of the city. In August of 1996 another accord was agreed to and once again elections were called for which were finally held in July of 1997. Unbelievably this resulted in the election of Charles Taylor, who in the interim had established his own political party called the NPP (National Patriotic Party), as president of the nation. That Taylor was elected with 75% of the vote is actually not so unbelievable when one realizes that the vote was massively influenced by the intimidation factor of his NPLF; a group that had so recently terrorized the nation. Many Liberians thought that by electing Taylor he would stop attacking them.

With Taylor’s election, while the violence never completely stopped, what is now called the First Liberian Civil War is considered to have come to an end. During its course more than 200,000 Liberians died, a figure representing one of every 17 people in the nation—more than 5% of the total population. In addition over one million Liberians were displaced, forced into refugee camps or fled the country. By any measure, what occurred in Liberia during the eight years between the 1989 coup against Samuel Doe (and recall that Doe himself was no paragon of virtue, logging plenty of murders and human rights abuses of his own) and the election of Charles Taylor, was a humanitarian disaster of mammoth proportions. In 1997 most Liberians thought they could now look to the future with some hope that the violence in their nation was finally at an end.

Alas, it was not to be.

What is now called the second Liberian civil war began in April, 1999 when Liberian dissidents opposed to Charles Taylor invaded Liberia from the neighboring country of Guinea. The dissident group, which was backed by the Guinea and Sierra Leone governments, was called Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD). It was comprised mostly of Krahn and Mandinka [2] ethnic fighters who at one time would have been loyal to Samuel Doe. In 1999 Sierra Leone and Guinea were dealing with their own rebellions and the one in Sierra Leone, by a group called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF)[3], was particularly violent, replete with RUF committed rapes, mutilations and killings of innocent civilians. The RUF was supported by and partially created by Taylor. The two countries, therefore, had a vested interest in taking Taylor out. Against the LURD forces Taylor used his former NPFL fighters mixed with what he considered his most elite force of NPFL veterans, a group he had created called the Anti-Terrorist Unit (ATU).

In September of 2000 Taylor’s forces launched a counter-attack on Guinea from Liberia while his RUF allies attacked government troops in Sierra Leone. After initial successes in the campaigns, by January of 2001 Taylor’s forces and allies were being pushed back on both fronts. Soon the LURD rebels were posing a major threat to Taylor’s army and Liberia was engaged in a complex conflict with Sierra Leone and the Guinea Republic. With his support of the RUF rebels in Sierra Leone and the rebellion in Guinea, Taylor also drew the ire of Great Britain and the United States; and those two countries increased their pressure on the Liberian government with increased financial support for Guinea and Sierra Leone.

Through the first 9 months of 2002 the LURD forces advanced through the Liberian countryside, closer and closer to Monrovia, at one point prompting Taylor to call a general state of emergency. In May, 2002 panic was induced in the Liberian capital when LURD troops attacked the town of Arthington, just 20 kilometers away; but by September Taylor’s forces had pushed the rebels back and the emergency declaration was lifted. In early 2003 another rebel group became active in Liberia putting additional pressure on Taylor’s government. This group was called the Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL) and it was apparently created by the government of the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (The Ivory Coast) in response to Taylor’s support of rebels in that country. After a period of relative calm a new round of fighting started in March of 2003. By May the LURD and MODEL rebels controlled two thirds of the country between them and the LURD group had closed in on and was shelling Monrovia, causing many civilian deaths and displacing many thousands more from their homes.

In early June of 2003, with the violence escalating and civilian deaths mounting, a conference was convened by the chairman of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in the city of Accra in the nearby country of Ghana with the aim of brokering a peace in Liberia. Partly as a result of the organized efforts of a coalition of thousands of Muslim and Christian Liberian women demanding an end to the conflict, even Taylor’s government was compelled to attend the talks and negotiate with the rebel groups.[4] Nevertheless, the violence in Liberia continued and by July Monrovia was under siege by the LURD rebels and in danger of being occupied. The situation prompted the United States to send its own warship and troops to protect its embassy and to remove U.S. citizens from the country. Finally, after 11 days of intense fighting between LURD forces and Taylor’s army in and about Monrovia that left hundreds of dead in the capital, on July 29th the LURD delegation at the Accra peace conference agreed to a cease fire and to allow ECOWAS peace keeping troops to enter Monrovia. Following this, on August 11th Charles Taylor resigned the Liberian presidency and went into exile in Nigeria. On August 14th the LURD rebels formally ended their siege of the city. After nearly 14 years of violence and turmoil, during which over 250,000 people were killed and untold numbers were displaced and/or abused, the Liberian civil wars were finally over.

In alignment with the Accra peace accords a National Transitional Government was established in Liberia to be followed two years hence by national elections to determine who would become the country’s next president. During the two year transitional period, overseen by thousands of United Nations peace keeping troops, the 100,000 or so fighters of the various warring factions in the country were gradually disarmed and a program was launched to re-integrate them into society. In October of 2005, under the watchful eye of the UN peace keeping force, the election was held with 23 candidates vying for the Liberian presidency. With no candidate receiving the required majority of votes as required by Liberian law, a second election was held in November of 2005. This time a woman named Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, a Harvard trained economist of mixed indigenous and Americo-Liberian descent and William Tolbert’s former Minister of Finance in 1979-80, took 59% of the vote. She assumed the presidency on January 16, 2006 and, with her re-election in 2011, has held the office across the nine years since, though not without some controversy. In 2009 the final report of the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an organization created by Parliament to investigate and report on the gross human rights violations that took place during the civil wars and who was responsible for them, included Sirleaf on its list of 50 people who should be banned from politics due to their actions and associations during the civil war. Sirleaf, who had been an ardent opponent of Samuel Doe, having been imprisoned during his administration, acknowledges supporting Charles Taylor early in the civil war but states that she disassociated from him upon realizing what he was doing. She apologized to the Liberian people for her Taylor association and the Liberian Supreme Court ruled that the report’s ban was unconstitutional, hence she has remained in office.

The full findings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report are revealing, citing a number of causes for the civil wars and naming, as well, many of the human rights abuses that took place during them. Chief among these, per the report, are the following:

* The conflict in Liberia has its origin in the history and founding of the modern Liberian State.

* The major root causes of the conflict are attributable to poverty, greed, corruption, limited access to education, economic, social, civil and political inequalities; identity conflict, land tenure and distribution, etc.

* All factions to the Liberian conflict committed, and are responsible for the commission of egregious domestic law violations, and violations of international criminal law, international human rights law and international humanitarian law, including war crimes violations.

* All factions engaged in armed conflict, violated, degraded, abused and denigrated, committed sexual and gender based violence against women including rape, sexual slavery, forced marriages, and other dehumanizing forms of violations…

*All factions and other armed groups recruited and used children during periods of armed conflicts.

*Lack of human rights culture and education, deprivation and over a century of state suppression and insensitivity, and wealth accumulation by a privileged few created a debased conscience for massive rights violations during the conflict thus engendering a culture of violence as means to an end, with an entrenched culture of impunity.

As can be seen from the above, the human rights abuses that took place in Liberia and neighboring countries across the years of the civil wars were not committed only by Taylor and his NPLF/RUF rebels. All factions, including Prince Yormie Johnson’s INPLF, the Liberian government troops of Samuel Doe and later the IGNU, the LURD/MODEL rebels who fought Taylor’s regime in the second civil war, and even the the ECOWAS peace keeping troops engaged in these actions and were and are culpable. For his part, Charles Taylor was the subject of a sealed indictment issued by the Special Court of Sierra Leone [5] in March of 2003, before the second civil war was even over. The indictment charged Taylor with war crimes, claiming that he had created the RUF rebels in Sierra Leone and that they had engaged in a wide range of brutalities against civilians, including rapes, hacking off limbs and forcing children to become soldiers. As noted above, Taylor fled to Nigeria in August of 2003. In 2006 President Sirleaf formally requested his extradition, which Nigeria granted, only to have Taylor pull one of his disappearing acts. Three days later he was apprehended at a border crossing, reportedly with a large amount of cash and heroin. He was returned to Sierra Leone for trial, but out of concern that he still had influence in that country Taylor’s trial was ultimately held in the Netherlands at The Hague. After extended legal proceedings, in 2012 Taylor was convicted of 11 counts of aiding and abetting war crimes and crimes against humanity. He appealed the decision but in 2013 the verdict was upheld and he is currently serving a 50 year prison sentence in England.

Recognizing the long history of human rights abuses in Liberia, a country in which roughly 5% of the population (the Americo-Liberians) dominated the remaining 95% (the indigenous Africans) for 130 years, the commission accurately concluded that a major cause of the Liberian civil wars was that, “Lack of human rights culture and education, deprivation and over a century of state suppression and insensitivity, and wealth accumulation by a privileged few created a debased conscience for massive rights violations during the conflict thus engendering a culture of violence as means to an end, with an entrenched culture of impunity.” In essence the commission’s findings highlight the truth in Pope Paul VI’s famous statement: “If you want peace work for justice.”[6] At the root of the Liberian civil wars was 130 years of injustice brought about by the systematic denial of the most basic of human rights to the vast majority of its citizens. It is no accident that many of the great documents of history, from Magna Charta (1215) to the US Declaration of Independence (1776) and Bill of Rights (1789); and from the French Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789) to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), all acknowledge the importance of these rights and their intrinsicness and their nativeness to human beings. In his historic April, 1963 encyclical Pacem In Terris (Peace on Earth), written during the height of the Cold War, Pope John XXIII made the eloquent connection between the recognition of these rights and the accomplishment of real peace on earth. So did President John F. Kennedy a few weeks later when he delivered his famous “Peace Speech”[7] at American University. Both men knew their history, for history is replete with the wars and bloodshed that result when one group of people seeks to deny these rights, which belong to each person by birth, to another group of people. As history has shown, when governments or rulers deny these rights to their people, it is ultimately at the government’s or ruler’s peril and not the other way around; for in the inevitable quest for justice the sources of injustice are dispensed with, as if by natural law.

Understanding the above, Liberia’s story can be seen as a modern cautionary tale; an illustration of what can happen when a people and a nation lose sight of these fundamental truths and the fact that the prime reason for government in the first place is the securing and protecting of these rights. Liberia will recover as a nation to the degree that it comes to terms with these things and understands them, both in its past and in how it, as a nation, moves into the future. A small but expanding group of people led by a survivor of the civil wars turned human rights activist named Jay Yarsiah,[8] has taken on this task for his country and the neighboring countries of West Africa. In the immediate wake of the Liberian civil wars, due to a chance internet contact, Jay found out about a group called Youth for Human Rights International (YHRI)[9] that has as its mission the education of youth and the raising of awareness of the necessity for human rights around the world. Through this contact Jay soon met an American YHRI director named Tim Bowles [10]and the two of them, with the support of YHRI, set about creating what is now called the African Human Rights Leadership Campaign which is carrying forward their human rights awareness programs in Liberia and the other nations of West Africa. Though held back by the recent devastating Ebola epidemic[11] and the myriad problems that afflict most of the lesser developed nations on this planet, Liberia is, today and at last, moving forward on an honorable path.

At the very end of his American University speech in June of 1963 President Kennedy, in quoting from the bible, emphasized the relation between human rights and the attainment of real peace: “When a man’s ways please the Lord,” Kennedy said, “he maketh even his enemies to be at peace with him.” JFK then went on to say, “And is not peace, in the last analysis, basically a matter of human rights—the right to live out our lives without fear of devastation—the right to breathe air as nature provided it—the right of future generations to a healthy existence?”

Kennedy’s words resonate as true today as the day he spoke them. Indeed, they always have been and always will be true. Due to the efforts of men like Jay Yarsiah and Tim Bowles and groups like Youth for Human Rights International, a country, Liberia, that has so recently witnessed some of the worst Human Rights violations of which man is capable, may yet become not only the hope of Africa, but a beacon of real peace, and an example for the rest of the world to follow.

Copyright © 2015

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

To support Jay, Tim and the African Human Rights Literacy Project with a donation just click the link below:

https://www.gofundme.com/africanliteracy

[1] The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) was formed in May of 1975 around the purpose of promoting the mutual economic interests of its member nations, which include, besides Liberia, the countries of Nigeria, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea and Sierra Leone among others.

[2] The Mandinka, Malinke (also known as Mandinko or Mandingo) is a West African ethnic group with an estimated global population of eleven million. They belong to the larger Mandé group of peoples.

[3] The Revolutionary United Front (RUF) was a rebel army that fought a failed eleven-year war in Sierra Leone, starting in 1991 and ending in 2002. It later developed into a political party, which existed until 2007. The RUF initially formed as a group of Sierra Leoneans which led elements of Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL) across the border in an attempt to replicate Taylor’s earlier success in toppling the Liberian government. At first, the RUF was popular with Sierra Leoneans, many of whom resented a government elite seen as corrupt, and looked forward to promised free education and health care and equitable sharing of diamond revenues. However, the RUF developed a reputation internationally for its terrible cruelty towards the civilian population during its decade-long struggle, especially its practice of hacking off limbs to intimidate and spread terror among the population, and its widespread use of child soldiers.

[4] In 2003 during the Second Liberian Civil War, a group known as Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace forced a meeting with President Charles Taylor and extracted a promise from him to attend the Accra peace talks in Ghana to negotiate with the rebels from Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD) and Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL). A delegation of these Liberian women also went to the Accra conference to continue to apply pressure on the warring factions during the peace process. The women of Liberia became a political force against violence and against their government. Their actions helped bring about an agreement during the stalled peace talks and, as a result, helped to achieve peace in Liberia after the 14-year civil war. They later helped bring to power the country’s first female head of state, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf.

[5] The Special Court for Sierra Leone, otherwise called the “Special Court” or the SCSL, is a judicial body set up by the government of Sierra Leone and the United Nations to “prosecute persons who bear the greatest responsibility for serious violations of international humanitarian law and Sierra Leonean law” committed in Sierra Leone after 30 November 1996 and during the Sierra Leone Civil War.

[6] From the 1 January, 1972 “World Day of Peace” message by Pope Paul VI

[7] JFK’s speech at American University on June 10th, 1963 has been called the “Peace Speech” because its message represented a stunning shift away from the Cold War rhetoric of the times toward a policy of mutual respect and reconciliation with the Soviet Union. For more information on this speech please go to http://fromanativeson.com/2013/09/01/jfk-and-the-road-to-dallas-peace-speech-at-american-university-by-mark-arnold/

[8] Jay Yarsiah is a native Liberian who grew up in Liberia during the 14 year period of the civil wars and who personally witnessed some of the abuses and carnage resulting. His experiences during the civil wars inspired his involvement and work for human rights in West Africa following them. For Jay’s story in his own words please go to http://fromanativeson.com/2015/01/17/from-the-other-side-of-freedom-the-remarkable-true-story-of-jay-yarsiah/

[9] For more information on Youth for Human Rights International and a full description of its programs please go to http://www.youthforhumanrights.org/

[10] Tim Bowles is an American attorney from Pasadena, California who is also a director in Youth for Human Rights International. He has been working in collaboration with Jay Yarsiah for the cause of human rights in Africa since 2006.

[11] Ebola virus disease (EVD; also Ebola hemorrhagic fever, or EHF), or simply Ebola, is a disease of humans and other primates caused by ebola viruses. Signs and symptoms typically start between two days and three weeks after contracting the virus with a fever, sore throat, muscular pain, and headaches. Then, vomiting, diarrhea and rash usually follow, along with decreased function of the liver and kidneys. At this time some people begin to bleed both internally and externally. The disease has a high risk of death, killing between 25 and 90 percent of those infected with an average of about 50 percent. This is often due to low blood pressure from fluid loss, and typically follows six to sixteen days after symptoms appear. In March 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a major Ebola outbreak in Guinea, a western African nation. The disease then rapidly spread to the neighboring countries of Liberia and Sierra Leone. It was the largest Ebola outbreak ever documented, and the first recorded in the region. On 8 August 2014, the WHO declared the epidemic to be an international public health emergency and urged the world to offer aid to the affected regions. As of April 2015, the West African Ebola outbreak had resulted in over 20,000 cases of the disease with over 10,000 deaths. For the week ending 8 April, 2015 the WHO announced just 30 confirmed new cases for the week, the lowest total in a year, indicating the epidemic is perhaps ending.

4 Responses

Very good post! We will be linking to this great post on our site.

Keep up the good writing.

Thank you very much and am very glad you found the post informative and useful!

thanks for this site i like it

You’re Welcome!