Note: Presented here is the 5th and final installment of the “JFK and the Road to Dallas: Ramping Up The Vietnam War” series. The whole purpose of this series is to enlighten the reader on the circumstances that led to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, the roots of which extend back to World War II. To understand the situation faced by JFK when he took office as President in 1961, this information is vital. The series should be read in sequence unless you already have a good understanding of the people and events involved in Vietnam and regarding Vietnam in the 1940s and ’50s, All of the prior installments can be found in this blog site (fromanativeson.com). With that understood, here is “Ramping Up The Vietnam War Part V: 1956-1960-The Growing Insurgency.” MA

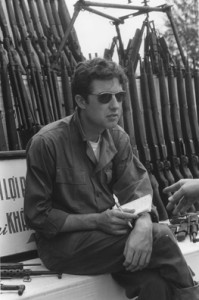

Ed Lansdale, his work in Vietnam completed, departed Saigon at the end of 1956 and returned to the United States, leaving in his wake the now established South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem. Despite the arrival in the South of the one million Catholic refugees as a result of Lansdale’s Operation Exodus[1]; and notwithstanding the Diem engineered and controlled election of October 1955 [2], the bulk of Vietnamese in the South, who weren’t Catholic, looked askance at the newly installed President and his government. Before too much more time went by Diem would give them ample reason to. It is not that those in the U.S. who were pulling the strings to establish Diem’s government were unaware of this fact; it’s just that, in order to establish an anti-communist government in South Vietnam, they had no one else. Diem’s lack of affinity for his non Catholic people, and theirs for him, would become a problem almost immediately and remain so until 1963, when he was murdered during a coup three weeks before JFK himself was assassinated. The Pentagon Papers does allude to Diem’s public relations problem, but in the following quote it seems more concerned with creating the false impression that Diem was a miracle worker:

“It should be recognized, however, that whatever his people thought of him, Ngo Dinh Diem really did accomplish miracles, just as his American boosters said he did. He took power in 1954 amid political chaos, and within ten months surmounted attempted coups d’état from within his army and rebellions by disparate irregulars. He consolidated his regime while providing creditably for an influx of nearly one million destitute refugees from North Vietnam; and he did all of this despite active French opposition and vacillating American support. Under his leadership South Vietnam became well established as a sovereign state, by 1955 recognized de jure (according to the law) by 36 other nations. Moreover, by mid-1955 Diem secured the strong backing of the U.S. He conducted a plebiscite (a vote of all citizens) in late 1955, in which an overwhelming vote was recorded for him in preference to Bao Dai; during 1956, he installed a government-representative in form, at least-drafted a new constitution, and extended GVN (Government of Vietnam, Diem’s government) control to regions that had been under sect or Viet Minh rule for a decade; and he pledged to initiate extensive reforms in land holding, public health, and education. With American help, he established a truly national, modern army, and formed rural security forces to police the countryside. In accomplishing all the foregoing, he confounded those Vietnamese of North and South, and those French, who had looked for his imminent downfall.” [3]

In light of what we have learned about the CIA’s Ed Lansdale and what he did with the Saigon Military Mission in Vietnam[4], the above statement is incredibly misleading. The miracles attributed to Diem in this document were, for the most part, actually those of Lansdale and the SMM. A truer statement about Diem during this time period is provided by Neil Sheehan[5] in his classic book of the Vietnam War, “A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Van and America in Vietnam.” In his book, referring to Lansdale’s relationship to Diem, Sheehan writes: “America’s new hope in Saigon, a Catholic mandarin (civil servant) named Ngo Dinh Diem, had faced more enemies than it seemed possible to vanquish. Arrayed against him were rival politicians, pro-French dissidents in the South Vietnamese Army, and two religious sects and a brotherhood of organized criminals. Lansdale had arranged the defeat of them all. He had denied the Vietnamese Communists the chaos that would have permitted them to take over Vietnam south of the 17th parallel without another war. He had convinced the Eisenhower administration that Diem could govern and that South Vietnam could be built into a nation that would stand with America.”

Lansdale may have been gone, but South Vietnam, as the unique creation of the United States, would become its national albatross for nearly the next 20 years. Throughout 1957 Diem concentrated on the creation of a modern army for South Vietnam. Using what was left to him from the Bao Dai government, and with the help of the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), the goal was to create an army capable of withstanding and defeating the Viet Minh should they invade the South. The problem was the “invasion” had already begun and the coming war was not one that would be fought in the classic army vs. army style. When the country was temporarily divided at the 17th parallel by the 1954 Geneva Accords the Viet Minh army was to return to the North, while the French and any French Vietnamese fighters and supporters were to go to the South. But not all of the Viet Minh went North. A number of them remained in the South and they and the remnants of the suppressed Binh Xuyen and the other sects became a “5th column”[6] activity agitating against the Diem government. By 1957 they were mounting sporadic guerilla attacks against government held areas and installations and were being called “Viet Cong”, a term that simply means “Vietnamese Communist.”

In response to these needlings, which often were no more than bandit raids for food, the Diem regime became increasingly repressive. Even Life Magazine reporter John Osborne, in an otherwise positive article he wrote for the magazine in May of 1957, commented on the tactics Diem was using to suppress agitation in South Vietnam. The article was timed to coincide with Diem’s first state visit to the United States, which was taking place at the time. Osborne’s piece was entitled, “The Tough Miracle Man of Vietnam” and in it he commented that, “Behind a facade of photographs, flags and slogans there is a grim structure of decrees, political prisons, concentration camps, milder ‘re-education centers,’ secret police. Presidential ‘Ordinance Number 6’ signed and issued by Diem in January, 1956, provides that ‘individuals considered dangerous to national defense and common security’ may be confined by executive order in a ‘concentration camp.’…Only known or suspected Communists who have violated public security since July, 1954, are supposed to be arrested and ‘re-educated’ under these decrees. But many non Communists have also been detained. The whole machinery of security has been used to discourage active opposition of any kind from any source.”

With his intent being to wipe out any Communists in the South, Diem used his “Ordinance Number 6” to brutally repress anyone suspected of being Viet Minh or Viet Cong. As is always the case in such situations, the label “Communist” could be and easily was extended to anyone Diem considered the enemy. Those arrested were denied counsel and hauled before “security committees” which led to many of them being tortured and killed. Through such actions, except for the Catholics who depended on him, Diem was not making many friends amongst the people of South Vietnam.

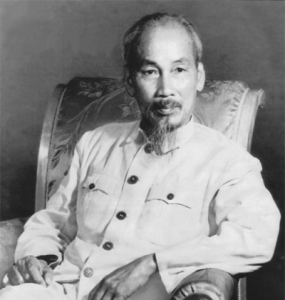

North Vietnam, during these early years of the American Vietnam War, was not much help to the Viet Minh and Viet Cong guerillas in the South. Ho Chi Minh’s government was dedicating all of its efforts to building up an economic infrastructure and economy for their nation. To accomplish this, radical land reforms were instituted in late 1955, and anyone opposed to them was hauled off and shot or put in a labor camp—actions that resulted in thousands of deaths. The North Vietnamese leader announced his strategy for his country in June of 1956 as follows: “Our policy is: to consolidate the North and to keep in mind the South. To build a good house we must build a good foundation…the North is the foundation, the root of the struggle for complete national liberation and the reunification of the country…Therefore, to work here is the same as struggling in the South…” [7]. The words sounded good, but many of those on the implementation end of this policy suffered.

As a result of the government suppression in the North, in 1956 peasant uprisings became rampant and thousands were either killed or exiled in an effort to quell the disturbances. In November of 1956 Hoh’s government acknowledged in a radio broadcast that mistakes were committed during the land reform and for the next 3 years the country embarked on a more moderate program of reforms.

Throughout the balance of 1956 and on into 1957, despite the problems with assistance from the North, the Viet Minh (Viet Cong) insurgency in the South expanded. By October of 1957 the sporadic guerilla actions had grown into a full scale terror campaign that included bombings and assassinations of South Vietnamese administrative officials, with over 400 being killed by year’s end; which of course ignited another round of Diem reprisals and efforts at repression. The situation ebbed and flowed like this until March of 1959. At that point Ho Chi Minh shifted his policy away from economics and announced a People’s War to unite all of Vietnam. The North established within its government the “Central Office of South Vietnam” and, to facilitate movement of soldiers and equipment to the South, construction started on what would become known as the “Hoh Chi Minh Trail”.

In July of 1959 an ominous event occurred when two U.S. military advisors, Major Dale Buis and Sgt.Chester Ovnand, were killed by Viet Minh guerillas at the town of Bien Hoa in South Vietnam. The two were the first Americans killed in action in Vietnam since Lt. Peter Dewey[8] was killed accidentally by the Viet Minh in Saigon in 1945.

The situation further deteriorated in 1960. In April of that year Diem was petitioned for reform of his increasingly fascist government by 18 prominent Vietnamese Nationalists in the South. He not only ignored them, but shut down opposition newspapers and arrested intellectuals and journalists accused of opposing him. In November of 1960 these and other abuses led to a coup attempt against Diem by dissident South Vietnamese army officers. (Earlier that same month, in a very tight race against Richard Nixon, John Kennedy was elected President of the United States) The coup failed, which resulted in widespread and savage Diem reprisals. Over 50,000 people suspected to be anti-government were arrested by Diem’s police force, which was controlled by his brother, the soon to be notorious Ngo Dinh Nhu.[9] Many people were tortured and murdered and as a result of Diem’s repression thousands of Southern Vietnamese fled to North Vietnam. A perhaps not so ironic aspect of this is that a number of them ended up returning to the South as Viet Cong to fight the government of the South Vietnamese dictator.

Such were the circumstances in Vietnam when JFK was inaugurated as President of the United States on January 20th, 1961. As the new President he inherited the growing insurgency and an impossible situation in Southeast Asia. In 1954 the United States went into Vietnam and for the next 20 years tried to do what the French could not: defeat a tough and seasoned enemy—the Viet Minh (later the North Vietnamese Army)—that was hell bent on kicking out the foreigners and re-uniting their country. The fact their leaders were Communists provided the perfect justification in those rabid anti-communist, Cold War years of the early 1950s. Through the CIA’s Saigon Military Mission initially, and later through military support and intervention, the U.S. propped up what would become a corrupt government and put it in the hands of a man, Diem, who would become a corrupt and cruel dictator; alienated from the bulk of his people, and incapable of instilling in them any sense of patriotism or loyalty to him.

We can see now what a massive mistake it was for the United States to ever have become involved in Vietnam; a mistake that 58,000 Americans paid the ultimate price for, as did untold numbers of Vietnamese. Kennedy did come to realize that mistake, but before he could implement his plans to handle it he made that fateful trip to Dallas.

Copyright © 2014

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] For a description of the CIA’s Operation Exodus please see Ramping Up The Vietnam War Part IV in this blog site.(fromanativeson.com)

[2] The October 1955 election is discussed in Ramping Up The Vietnam War Part IV, which is in this blog site. (fromanativeson.com)

[3] This quote is taken from the Gravel edition of the Pentagon Papers, Volume I, Chapter V “The Origins of the Insurgency in South Vietnam, 1954-60”

[4] For a description of Ed Lansdale’s and the Saigon Military Mission’s activities in Vietnam please see “Ramping Up the Vietnam War Part IV” in this blog site (fromanativeson.com)

[5]Neil Sheehan (born in 1936) has history as a reporter in Vietnam, first as UPI Bureau Chief in Saigon (1962-64) and later (1965) as a correspondent for the New York Times. In 1966 he was assigned as the NY Times Pentagon correspondent. In 1971 he obtained the classified Defense Dept report that would become the Pentagon Papers from former Defense Dept analyst Daniel Ellsberg and started publishing them in the NY Times. The Nixon administration got an injunction against the Times forcing them to stop publishing the documents citing national security concerns. A few weeks later in a landmark First Amendment ruling the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Times with the result that the newspaper continued to publish the documents of the Defense Dept Report. Thus the Pentagon Papers were released. In 1988, after many years of work on it, Sheehan released his Pulitzer Prize winning book “A Bright Shining Lie: John Paul Van and America in Vietnam” based upon the life of one of the unique figures to emerge from the Vietnam War, John Paul Van, who was an American military officer early in the war and an official for the Agency for International Development later in it. In 1972 Van was killed in Vietnam in a helicopter crash. Today Sheehan lives in Washington DC with his wife and continues to speak and write on US foreign policy issues.

[6] A “5th column” is a clandestine group or faction of subversive agents who attempt to undermine a nation’s solidarity by any means at their disposal. The term is credited to Emilio Mola Vidal, a Nationalist general during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). As four of his army columns moved on Madrid, the general referred to his militant supporters within the capital as his “fifth column,” intent on undermining the loyalist government from within.

[7] From “The United States in Vietnam” published in 1969 by George Kahin and John W. Lewis

[8] The killing of Lt. Col Peter Dewey is discussed in Ramping Up The Vietnam War Part II which can be found at this blog site (fromanativeson.com)

[9] Ngo Dinh Nhu (7 Oct 1910-2 Nov 1963) was the younger brother and chief political advisor of South Vietnam‘s first president, Ngo Dinh Diem. Although he held no formal executive position, he wielded immense unofficial power, exercising personal command of both the Ngo family’s private army and the secret police.