Note: This installment is the 4th in the “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series, which is part of a larger project with the working title of “JFK and the Road to Dallas”. The goal of the “Ramping Up the Vietnam War” series is to enlighten the reader on the circumstances that led to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam—an involvement that began much earlier than many people in the United States realize. By the time JFK came to office in 1961 the U.S. had been overtly involved in Vietnam since the Viet Minh defeated the French at the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May of 1954; but before that had supported the French in their 8 year war to reclaim their Southeast Asian colony of Vietnam from the communist Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh army. To understand what JFK was dealing with as regards Vietnam while he was in office the information covered in this series is vital preamble. In this installment, Part IV, we cover the crucial period from the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu, to the 1954 Geneva Conference, which resulted in agreements as to the handling for Vietnam; and lastly, the CIA’s effort at subverting the Geneva Accords through the actions of the legendary intelligence officer Ed Lansdale and his Saigon Military Mission. To get the most out of this series please read it in sequence. All three prior installments can be found in this blog site. Thank You! MA

In January of 1954 the French were still fighting Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh in Vietnam and their eventual defeat was still four months into the future. Other than supplying the French with supplies and munitions the United States involvement in Vietnam to that point had been limited to intelligence operations and a few military liaison officers to oversee the French use of the millions of dollars worth of US equipment that had been sent. No US troops were on the ground fighting and no US planes flew Vietnamese skies. All the casualties to that point had been French and Vietnamese[1]. Nevertheless, at a National Security Council meeting on January 8th President Eisenhower, in discussing US objectives in Vietnam, made the following statement:

“The key to winning this war is to get the Vietnamese to fight. There is just no sense in even talking about United States forces replacing the French in Indochina. If we did so, the Vietnamese could be expected to transfer their hatred of the French to us. I cannot tell you how bitterly opposed I am to such a course of action. This war in Indochina would absorb our troops by the divisions!”

To elicit such a vehement response from the President it is obvious that someone at that NSC meeting must have broached the idea of sending US troops to Vietnam.

At the time Eisenhower made that statement most of the Vietnamese fighting in Vietnam belonged to the communist Viet Minh. The French goal in Vietnam was to defeat the Viet Minh and to re-establish their Vietnamese colony. Arming the Vietnamese and getting them to fight ran counter to French policy. Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh controlled the northern part of the nation and had established the Democratic Republic of Vietnam; while the French had established in Vietnam’s southern sector, an area formerly known as Cochin China, a puppet regime under former Vietnamese emperor Bao Dai called the State of Vietnam. Bao Dai had been educated in France and spent a great deal of his time on the French Riviera. Most Vietnamese felt no loyalty for him and hated the French. Eisenhower knew this and stated as much in his comment above. He also was aware, as he stated in his 1963 book “Mandate for Change”, that had elections been held in Vietnam at the time the French were fighting the Vietnamese in the early ‘50s Ho Chi Minh would have won easily. In Eisenhower’s words: “I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 per cent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh as their leader rather than Chief of State Bao Dai.”

Considering those circumstances, just how would you go about getting the Vietnamese to fight? Eisenhower did not address that question. The fact is there never had been a nation in Cochin China, or what soon would be called South Vietnam. The people in that part of Vietnam had no love for the French or Bao Dai and had no loyalty for a government that had never before existed for them. This was the problem the French had in Vietnam, and the one the U.S. was about to inherit in 1954. The nation and government had to be created first, loyalty established in the people for it, and only then could they reasonably be expected to fight for it. As we shall see, this was too big a task, not only for the French, but also for the United States.

From Eisenhower’s statement on January 8th it was clear that he was opposed to the entry of U.S. forces into Vietnam, whether to support the French, or to supplant them. Nevertheless, within a week of Eisenhower’s statement elements of his administration were making plans to involve the US in Vietnam in the event of French failure there. On January 14th, 1954 Secretary of State John Foster Dulles [2] said the following:

“Despite everything that we do, there is the possibility that the French position in Indochina would collapse. If this happened and the French were thrown out, it would, of course, become the responsibility of the victorious Vietminh to set up a government and maintain order in Vietnam…I do not believe in this contingency this country (the US), would simply say, ‘Too bad: we’re licked and that’s the end of it.’ / If we could carry on effective guerilla operations against this new Vietminh government, we should be able to make as much trouble for this government as they had made for our side…Moreover, the costs would be relatively low. Accordingly, an opportunity will be open to us in Southeast Asia even if the French are finally defeated by the Communists. We can raise hell and the Communists will find it just as expensive to resist as we are now finding it.”

On that very same day a meeting of the National Security Council agreed that, “…the Director of Central Intelligence (Allen Dulles, brother of John Foster Dulles), in collaboration with other appropriate departments and agencies should develop plans as suggested by the Secretary of State (John Foster Dulles), for certain contingencies in Vietnam.” The result of that directive was the creation by CIA Director Allen Dulles of what we know today as the Saigon Military Mission. With its creation the US was about to embark upon a tragic involvement in Vietnam that would not end for twenty years and that would cost the lives of 58,000 Americans.

Just what was the “Saigon Military Mission”? Ironically, it was not really a military operation. Basically it was the manifestation in fact of the idea John Foster Dulles had put forth in his January 14th statement: “If we could carry on effective guerilla operations against this new Vietminh government, we should be able to make as much trouble for this government as they had made for our side…We can raise hell and the Communists will find it just as expensive to resist as we are now finding it.” As a result of the National Security Council directive authorizing CIA Director Allen Dulles to, “develop plans as suggested by the Secretary of State (John Foster Dulles), for certain contingencies in Vietnam,” the Saigon Military Mission (SMM) came into being. In the event of French failure in Vietnam the SMM was to be the CIA’s vehicle in the country to harass, sabotage, infiltrate and subvert Ho Chi Minh’s effort to consolidate power and establish his government. It also would have the purpose of assisting to establish in Vietnam’s southern sector, using the CIA’s checkbook, a government loyal to the United States and opposed to Communism.

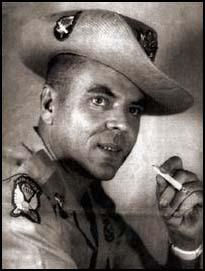

Remember, all of this planning was taking place months before the French had even been defeated. At a January 29th meeting of the President’s Special Committee on Indochina, attended by CIA Director Allen Dulles, his deputy General Charles Cabell, and former Manila (Philippines) CIA station chief George Aurell, it was determined that the man who would command the SMM would be none other than legendary CIA operative Ed Lansdale [3]. In 1954 Lansdale was riding high as a result of his successful mission to the Philippines, the purpose of which was to replace the existing President Elpidio Quirino. At the time the communist “Huk” insurgency[4] was taking place in the Philippines and Lansdale had used it to build up the repute of his handpicked future President, a man named Ramon Magsaysay. Tactics refined by Lansdale at this time included staging fake “Huk” attacks on villages, and having Magsaysay and his soldiers arrive just in time to defeat them. (These attacks were quite elaborate, including fake dead and fake executions) The villagers, thinking the attacks were real, considered Magsaysay a hero. His reputation spread and by 1953 he had won the election and supplanted Quirino as President. As a result Lansdale was considered the CIA’s top counter-insurgency and psychological warfare man and Allen Dulles wanted him to repeat his magic in Vietnam. Thus, the SMM had its commander.

As noted above, one of the goals of the SMM upon arriving in Vietnam would be to establish in the southern part of the country a pro-American government capable of resisting the Communists in the north. The thinking of American government officials at the time as regards Communist expansion has been described as “The Domino Theory.” This was best expressed by President Eisenhower in a news conference he gave on April 8th, 1954:

“You had a row of dominoes set up, and you knocked over the first one, and what would happen to the last one was the certainty that it would go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.”

The intention for this new government in South Vietnam was to make it the domino that would not fall, thus breaking the expected disintegration described by Eisenhower. To do this a new leader would be needed, as everyone knew that Bao Dai was unpopular and unwanted; and the solving of that problem was already underway.

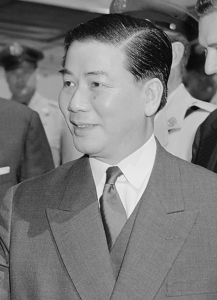

Ngo Dinh Diem was a Vietnamese, Catholic, anti-communist nationalist who was 53 years old in 1954. In the 1930s he had been minister of the interior in the Bao Dai French colonial government, but the appointment was short lived due to his support of creating a Vietnamese legislature, which the French opposed. During World War II the Japanese occupied Vietnam and toward the end of their occupation offered Diem the post of Premier in the Bao Dai puppet government they had established, which he refused. After the Japanese defeat in 1945 Diem communicated with Ho Chi Minh, but as a Catholic and anti-Communist he refused to join the Viet Minh and instead attempted to create an anti-Viet Minh nationalist group. This resulted in an order for his arrest by Ho’s government. With battles raging between the Viet Minh and the French, Diem was able to avoid arrest and moved south to Saigon, there creating the Vietnam National Alliance which called for France to make a commonwealth dominion of Vietnam, much like the British had done with their colonies. Diem’s activities with the Alliance succeeded in gathering support, to the point where the French, in an effort to accommodate upset Vietnamese nationalists, approached him about getting the current nominal head of state Bao Dai to join in the dominion idea. When Bao Dai then cut a deal with the French that Diem thought was weak, he left Saigon and moved north to the town of Hue, where he started working on plans to create a third political force in Vietnam, different from Communism and French colonialism.

Meanwhile, in an effort to create their own legitimate government for Vietnam, and to counter the Democratic Republic of Vietnam established by Ho Chi Minh, the French created the State of Vietnam with Bao Dai as Chief of State. Once more Diem was offered a key post, this time Prime Minister, which he again refused. Finally, in 1950, with a death order on him issued by the Viet Minh, Diem left Vietnam and went into exile. By 1951 he had landed in the United States where he was supported by Cardinal Francis Spellman, the ultra conservative Catholic Archbishop of New York. (no ordinary anti-Communist, Spellman was a supporter of Senator Joe McCarthy and his Communist witch hunts of the early ‘50s.) Diem lived in Spellman’s Maryknoll [5]seminary in New Jersey for the next three years and found in Spellman an anti-Communist Catholic like himself who could spring board his career. In the early ‘50s Cardinal Spellman was probably the most politically influential clergyman in the United States and was well connected in government circles. He had studied with Diem’s brother Ngo Dinh Thuc, himself a Catholic priest, in Rome in the 1930s, and supported Diem’s anti-Communist sentiments. Thus it was that on May 7th, 1953 he was able to arrange a meeting for Diem with a number of US Senators, government and media officials. Present at the meeting were Senators Mike Mansfield and John Kennedy, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, a representative from CBS and Dept. of State officials Edmund Gullion and Gene Gregory. Spellman introduced him as a Vietnamese nationalist and Diem then took questions on Indochina from the group, chiefly Kennedy and Douglas, for the next hour. Through that meeting and speaking engagements he was able to arrange, Spellman was making sure that the US knew it had a resource in Diem for what was to come in Vietnam. Later in 1953 Diem left the United States and continued his exile in Belgium. With events in Vietnam coming to a head, Diem’s life would soon change dramatically and forever.

Exactly one year after Diem’s meeting with Kennedy, Douglas and the others, on May 7th ,1954 the French Army was defeated after a 57 day siege by the Viet Minh at the town of Dien Bien Phu in northeastern Vietnam. France would soon, at last, be out of Indochina. Several months earlier plans had been made by France, the US, Great Britain and the Soviet Union for a conference to take place on resolving the issues of Southeast Asia. Also to be invited to the conference, which was to take place in Geneva, Switzerland, were the People’s Republic of China and representatives of the principal parties and states of Indochina. The conference started on April 26th and was ongoing at the time of the French defeat. The results of this conference, which concluded on July 20th, were the Geneva Accords of 1954. The Accords as agreed upon stipulated a handling for Vietnam as follows:

*Vietnam was to become an independent nation, formally ending 75 years of French colonialism. Cambodia and Laos were also given their independence.

*Vietnam would be temporarily divided for a period of two years. The ‘border’ was defined as the line of latitude 17 degrees north of the equator (the 17th parallel). The Accords prescribed the border purely as a means to “settle military questions with a view to ending hostilities…the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary”.

*Nationwide elections, conducted under international supervision, were scheduled for July 1956. The election result was to determine Vietnam’s political system and government.

*During the two-year transitional period, military personnel were to return to their place of origin: Viet Minh soldiers and guerrillas to North Vietnam, French and pro-French troops to South Vietnam. For a period of 300 days Vietnamese civilians could relocate to either North or South Vietnam.

*During the transition period, both North and South Vietnam agreed not to enter into any foreign military alliances or authorize the construction of foreign military bases.

While the Accords seemed reasonable enough, the negotiations leading up to them were tense and acrimonious. United States Secretary of State John Foster Dulles would not shake hands with or acknowledge the Chinese and Viet Minh representatives. British representative Anthony Eden, witnessing the discord, stated that he had, “never known a conference of this kind; the parties would not make direct contact and we were in constant danger of one or another backing out the door.” Ultimately, neither the United States nor the State of Vietnam (soon to be South Vietnam) would sign off on the Accords. In lieu of signing the US Under Secretary of State Walter Bedell Smith issued the following statement on behalf of his nation:

“The Government of the United States of America declares:

With regard to the aforesaid Agreements and paragraphs that (i) it will refrain from the threat or use of force to disturb them…and (ii) it would view any renewal of the aggression in violation of the aforesaid Agreements with grave concern and as seriously threatening international peace and security…In connection with the statement in the Declaration concerning free elections in Vietnam, my Government wishes to make clear its position…In the case of nations now divided against their will, we shall continue to seek to achieve unity through free elections, supervised by the United Nations to ensure that they are conducted fairly.”

Though it didn’t sign the Geneva Accords, on paper, at least, the United States supported free elections for Vietnam. It was a commitment that would not last long.

Two major events that would have lasting consequences for Vietnam occurred while the Geneva negotiations were underway. The first was that on June 1st, less than a month after the French defeat on May 7th, the chief of the Saigon Military Mission, Ed Lansdale, left Washington DC and arrived in Saigon to set up shop. The second was the return, on July 7th, of Ngo Dinh Diem to be Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam. With his French primary support departing, Chief of State Bao Dai, realizing Diem’s support in the US, had made the request for him to return. With Lansdale already on the ground in Saigon, it did not take long for he and Diem to start maneuvering to rid the nation of Bao Dai and put Diem in total control.

Installing Diem as President of what would be South Vietnam was only one aspect of what the SMM was to accomplish, however. There was still the “raising hell” part, and to do that Lansdale was joined on July 1st by another legendary CIA spook, Army Major Lucien Conein. Both Conein and Lansdale (who before he was through was being called a General) started their intelligence careers in the pre-CIA, World War II Office of Strategic Services and were not regular military, but used their ranks as a cover. Conein was of French ancestry, being born in Paris, but was raised by an aunt in the US. When World War II started he rushed to join the French army. With the collapse of France to the Nazi’s in 1940 he returned to the US, joined the OSS, was parachuted behind enemy lines in France in 1944, and fought with the French resistance until war’s end. With the formation of the CIA in 1947 Conein came on board immediately.

In Vietnam in 1954 the SMM cover was that they were assigned to the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) which is a designation for American military personnel in foreign nations involved in training that nation’s regular military. A short while after Conein arrived in Vietnam the balance of the SMM team arrived under the cover of MAAG. Lansdale, Conein and the SMM were about to go to work.

Lansdale divided the SMM personnel into two groups, one to work with him in the southern part of Vietnam while the other, under Lucien Conein, would go to the North and “raise hell.” The goal of the SMM in North Vietnam was to covertly disrupt in any way possible the ability of Ho Chi Minh and his Communist government to carry out its programs, consolidate power and to thereby prevent any attempted takeover of the South by the North. The ink on the Geneva Accords was barely dry when Conein and his group clandestinely entered North Vietnam. The actions they undertook there give the term “raising hell” new meaning. In order to sabotage the Hanoi bus system they polluted petroleum supplies with acid and put sugar in the fuel tanks of the busses and government trucks. They disrupted the mail by bombing post offices and they wrote and distributed millions of anti-Viet Minh leaflets. They counterfeited money and they put explosives in the coal used by trains which would detonate upon burning. They even had an almanac made of astrological predictions that foretold doom for the North and distributed it.

For all the turmoil these actions must have generated, the overall impact and disruption of the North was minimal—that is until the SMM pulled off the granddaddy of its covert ops in Vietnam. To understand this operation you must have a good grasp on the situation in South Vietnam (State of Vietnam) as it existed in September of 1954. With the French leaving any semblance of a government was leaving too, which wasn’t much. Without the French, Chief of State Bao Dai had no support and was not liked and not wanted by the people. Except for the French puppet State of Vietnam created a few years earlier there had never been a nation, let alone a government, in South Vietnam. To make matters worse there were a number of sects in southern Vietnam that recognized no authority but their own. The worst of these was a Mafia-like group that had its own 25,000 man army and went by the name of Binh Xuyen. At one point this group fought with the Viet Minh against the French but then turned and became pro French as a militia guarding Saigon. With the benign Bao Dai looking on Binh Xuyen controlled all the drugs, prostitution, gambling and police in Saigon. To establish a viable government in the South, which was the SMM’s intention, Binh Xuyen and the other sects would have to be dealt with.

Another, and more significant barrier to Lansdale, was the fact that Ngo Dinh Diem, the SMM’s man to replace Bao Dai, was Catholic while most of the people in the South were Buddhists or Taoists. Most Vietnamese Catholics resided in the Tonkin area of the North close to the port of Haiphong and were not particularly favored in the South. To have a stable government in the South with Diem at the helm, this was a situation Lansdale knew he had to handle. Thus was “Operation Exodus”[6] born—the SMM’s effort to relocate those Northern Catholics to the South and thereby provide Diem with the political base he would need to survive. To the world this operation simply looked like a logical response to the equally logical desire of those Catholics to leave the suppressive North, as was authorized by the provision in the Geneva Accords which gave people 300 days to relocate to the North or South as they wished. The reality was something else again. As “Operation Exodus” demonstrated, looks can be deceiving.

How would one go about convincing roughly 1 million people, who had lived on the same land and in the same villages for generations, to suddenly pack up and move hundreds of miles to the south? We in the United States, whether in the mid 1950’s or in 2014, have little to no appreciation for the village tradition of the Vietnamese. These people were rooted to their lands and it would take something extraordinary to get them to leave. This was a job tailored beautifully to the psychological warfare skills of the CIA’s Ed Lansdale. He had Lucien Conein’s northern SMM group launch a black propaganda leaflet and flier campaign against Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh that claimed that the Viet Minh would be carrying out reprisals against northern Catholics. Ingeniously the leaflet content was made to appear like it was taken from Viet Minh plans. They also spread leaflets stating that the United States would soon become involved in Vietnam militarily and intended to use nuclear weapons against the North. In addition to these tactics Lansdale had Diem contact Catholic bishops in the North to convince them to move their people to the South. From this action was born the slogan, “The Blessed Virgin has gone south,” implying that it was the duty of Catholics in the North to follow.

As a result of these and similar actions about one million people, mostly Catholics, between late 1954 and the first few months of 1955, were uprooted from their homes and shipped south. They were transported at US expense (roughly $93 million) via the US Navy and the CIA proprietary airline known as Civil Air Transport. To handle this incoming horde, at Lansdale’s suggestion Diem established a refugee commission whose actions were coordinated by the US Military Advisor Assistance Group (MAAG) for the purpose of receiving and settling the refugees in the South. To accomplish this refugee relocation Diem provided land in the area around Saigon and the refugees, as long as they were Catholic, were given money, food, housing, clothing and livestock. Any non-Catholic refugees coming south were left to fend for themselves, unassisted in any way. Ultimately these Catholics wound up in key Government positions and in key villages around the South and provided Diem with a base of support that, without Lansdale, the SMM and “Operation Exodus”, he would not have had.

The next major step for the SMM was to get rid of Chief of State Bao Dai, who was often out of the country in France, and establish Ngo Dinh Diem as the sole South Vietnamese ruler. This time the mechanism to be used would be an election that Diem would closely control. In 1955 Bao Dai had tried to dismiss Diem from his Prime Minister post, but Diem simply ignored him and, at Lansdale’s prompting, he called for the election, which took place on October 23rd of that year. Through sending thugs to polling places to enforce votes for himself and with his own people counting the ballots, this farce of an election resulted in a landslide for Diem with a ridiculous 98% of the vote. Even Lansdale tried to get him to report a more reasonable 60 to 70% of the vote, but Diem refused. With the rigged election in his favor, 3 days later, on October 26th, 1955, Diem announced himself as President of the newly created Republic of Vietnam. Within a short time this new government was recognized by France, the United States, Japan, Great Britain, Australia, New Zealand, Italy, Thailand and South Korea.

Thus was created in South Vietnam, through the actions of the CIA’s Ed Lansdale and the Saigon Military Mission, an anti-communist nation, the Republic of Vietnam, which US leaders figured would, with US support, serve as a block to communist expansion efforts in Southeast Asia. With neither the United States nor South Vietnam signing the 1954 Geneva Accords it was a foregone conclusion that the called for elections in 1956 to unify the country would not happen. (In July of 1955 Diem announced that South Vietnam would not participate in any such election.) Stabilizing the Diem government required other actions from the SMM, such as using the CIA’s checkbook to buy off the leaders of independent religious sects that controlled their own armies; and buying the soldiers necessary for Diem to defeat the ruthless Binh Xuyen sect. Lansdale even prevented one of the generals in Diem’s fledgling army from staging a coup to overthrow the new ruler. Without Lansdale and the SMM, considering the barriers and opposition he faced, Diem would have had no chance, and the South would have fallen to Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh in short order.

Instead, because of Lansdale and the SMM, by 1956 the United States had its ally in South Vietnam, and the twenty year American war there was just getting started.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2014

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] The first US casualty in Vietnam took place shortly after the end of World War II in September, 1945 when an OSS officer, Lt. Col. A Peter Dewey was shot and killed by Viet Minh guerillas who mistook him for a French officer. This is covered in more detail in “Ramping Up The Vietnam War Part II” earlier in this series.

[2] For more information on the brothers John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles please see “Fox in the Henhouse: The Story of Allen Dulles”. The article can be found in the “Politics” section of this blog site.

[3] Edward Geary Lansdale (1908-1987) had a long intelligence career starting with the World War II OSS in 1943 and continuing with the Central Intelligence Agency through the ‘50s and early ‘60s. In terms of his effect on the United States and the world, other than Alan Dulles himself, no CIA operative had a greater impact than Ed Lansdale. A strong argument could be made that, as a result of his role with the Saigon Military Mission and with the creation of South Vietnam as a US ally, no other single American had more responsibility for creating the conditions that resulted in the American Vietnam War. Lansdale impacted American pop-culture as well. In 1958 a novel entitled “The Ugly American” was written loosely based on Lansdale’s career in Asia. The novel was made into a movie starring Marlon Brando in 1963.

[4] By the early 50’s the CIA was involved in covert operations in the Philippines supposedly in response to the communist HUK guerilla movement there. The acronym “H.U.K.” stands for “Hukbo ng Bayan Leban sa Hapon”. In native Filipino tongue this means “Peoples anti-Japanese Army”. The Philippines had been occupied by the Japanese in World War II and the HUKs resisted them. In 1946, when the Philippines were granted independence by the U.S., elections were held. Some HUKs won seats in the Filipino Congress but were then unseated by the ruling party after the elections. The HUKs retreated to the jungle and started their rebellion. As they had Communist leadership and the Cold War was in full bloom they became logical targets of the CIA. In reality the HUKs were not the threat they appeared to be.

[5] Maryknoll is a name shared by three organizations (two religious institutions and one lay ministry) that are part of the Roman Catholic Church: Maryknoll Fathers and Brothers (Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America; Maryknoll Society), Maryknoll Sisters (Maryknoll Sisters of St. Dominic), and Maryknoll Lay Missioners. The organizations are independent groups with shared history that work closely together with the overseas mission activity of the Catholic Church particularly in East Asia, China, Japan, Korea, Latin America and Africa. The organizations officially began in 1911, founded by Thomas Frederick Price, James Anthony Walsh, and Mary Joseph Rogers. The name Maryknoll comes from the hill outside Village of Ossining, Westchester County, New York, which houses the headquarters of all three. Members of the societies are usually called Maryknollers

[6] “Operation Exodus” has also been called “Operation Passage to Freedom”. For simplicity and continuity I am using “Operation Exodus” in this article.