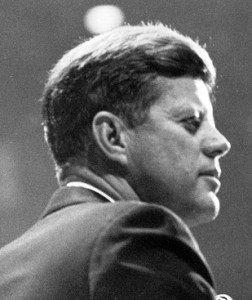

Note: The irony of JFK’s “Peace Speech” at American University is that it was more favorably received and more broadly publicized in the Soviet Union than it was in the United States. As you will recall from the prior article discussing Kennedy’s speech, [1] a Communist Chinese delegation had arrived in Moscow strategically timed to take advantage of the predicted failure of the Soviet test ban negotiations with the United States by prevailing upon the Soviets to adopt a more hard line stance with the U.S. and to return to the intractable views of earlier Cold War years. The Chinese had prepared an Open Letter to the Soviet People expressing these views that was awaiting approval by the Soviet government. The publishing of this letter by the Soviets would, in effect, be an acknowledgement that Khrushchev’s attempt at peaceful co-existence with the United States had failed and that a hard-line approach to the West, with all the resultant tensions and threats of war, would once again become official Soviet policy. Very few people in the United States knew how much was at stake during the first twelve hours after Kennedy delivered his speech. A turning point of history was at hand. If the Soviets went ahead with the Chinese letter it would be a rejection of the principles of peace JFK had presented in his talk. Finally, as Norman Cousins states in “The Improbable Triumvirate”:

“…the news broke in Moscow—the news about President Kennedy’s talk. The full text was published in “Izvsetia”. [2] The Russians had always been touchy about what they considered to be American ignorance or insensitivity to their colossal loss of life and property in World War II compared to that of the United States. When, therefore, President Kennedy paid eloquent tribute to the suffering of the Russian people in the war and to their basic yearning for peace, he touched a responsive chord in the Russian soul.”

The immediate result of Kennedy’s speech was that the Soviets spurned the Chinese efforts at enforcing their hard line views and had opted instead for the Khrushchev-Kennedy peaceful co-existence policy. While JFK’s American University address was broadly published in the Soviet Union, few Americans were informed of either the speech or the Soviet response to it. As James Douglas points out in his book “JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters”:

“At the same time that the American University address was highlighted by the Soviet media, it was ignored or downplayed in the United States. Few Americans even knew Kennedy had given a groundbreaking speech on peace, much less what was in it. That has remained true to this day. The American media response to the speech was, and has been, almost total silence. It was as if someone had unplugged the president’s microphone as soon as he began talking about peace.”

Despite the media silence in his own nation, with his “Peace Speech”, John Kennedy had started to clear the way with our Cold War adversary to a restoration of mutual trust, mutual respect and a possible future without the threat of nuclear war. The door was now open for at least some form of nuclear test ban treaty. It remained for the United States and the Soviet Union to walk through it….MA

_____________________________________

Following John Kennedy’s ground breaking speech at American University, it wasn’t long before the Russians indicated that they were ready to proceed with negotiations towards accomplishing a limited nuclear test ban treaty confined to atmospheric testing only. The idea of a partial, or limited, nuclear test ban agreement had been brought up several times before in earlier stages of the test ban negotiations between the U.S. and the Soviet Union; but always Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had insisted on a treaty covering all nuclear testing, including underground and the sea, or no treaty at all.

As noted in a prior article in this series [3], earlier in the year the Test Ban treaty negotiations had bogged down on the question of the number of inspections the U.S. was insisting were necessary to verify Soviet compliance to the underground testing ban. There had been a confusion wherein the Soviets had understood that the U.S. was requiring three inspections annually, whereas the actual number was eight. Based on the assumption of three inspections, Khrushchev had gone to his Council of Ministers and had gotten them to agree that three was acceptable. When the Soviet negotiators returned to the conference table with this information they were shocked to discover the U.S. was now demanding eight. Convinced now that the U.S. wanted the extra inspections for espionage purposes and was not sincerely interested in a test ban treaty, Khrushchev broke off the negotiations and forward motion on the treaty stopped.

The limited test ban resolution proposed by Senators Hubert Humphrey and Thomas Dodd in the Senate on May 27th, 1963 [4], two weeks before JFK’s American University address, had the advantage that it bypassed the disputed inspections point because it dealt with atmospheric testing only, which would not require inspections. As noted above, however, in the past this had not been acceptable to Khrushchev. Without something to restore some level of trust, and therefore a willingness to communicate in a mutually respectful environment, there was no hope for a test ban treaty, limited or otherwise.

That “something” was provided by Kennedy’s American University speech. As Norman Cousins notes in his book, “The Improbable Triumvirate”:

“…he (Kennedy) spoke realistically about the things that were necessary and therefore possible in a joint program for peace…If the President had confined himself in his talk to the test ban treaty, it is possible the proposal would have been rejected. But by going far beyond the treaty and by defining the realistic basis for further agreements between the two countries, the President opened up a whole catalogue of reasonable expectations. The President did not minimize the ideological differences between the two countries, nor did he provide the slightest basis for the supposition that the United States might be softening its stand on Berlin or any of the other basic elements in American policy. The Cuban Crisis had provided all the evidence that might be needed on that score. But what the talk did do was recognize the imperatives of an atomic age that called for a new sense of proportion and a new awareness of a common destiny.”

Kennedy’s American University talk had succeeded in bringing about a hopeful and positive atmosphere in which a limited test ban treaty could realistically be considered. In response to the renewed Soviet willingness, Kennedy once again dispatched Averell Harriman, the man to whom he had entrusted the Laos neutrality negotiations, [5] to the Soviet Union to complete negotiations for a limited test ban treaty. While there Harriman had three separate interviews with Chairman Khrushchev between July 15th and July 26th with the result that on July 25th, 1963, a limited test ban treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union banning nuclear atmospheric testing was agreed to and initialed.

As difficult as it had been to get the limited test ban treaty this far, major hurdles still lay ahead. The treaty now had to be approved by the United States Senate where many were opposed to the idea of a test ban treaty as being destructive of national security. Getting a two thirds majority, the Constitutional requirement for approving a treaty, from that bunch would be a daunting task.

With the initialing of the limited test ban treaty JFK commenced the process of marshalling the resources and personnel he knew he would need to get the agreement passed in the Senate. He was well aware of past failures by U.S. Presidents in this regard, specifically Woodrow Wilson with his failure to get United States involvement in the League of Nations approved in the Senate at the end of the World War I. As a result of the work of groups such as “The National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy” (SANE), a group founded by Norman Cousins and others in 1957 in response to the continued development and open air testing of nuclear weapons, public awareness on the dangers of these weapons and the proliferation of air born radiation was rising. Even so, at the point the limited test ban treaty was initialed in July, 1963, Kennedy estimated they would be substantially short of the 2/3rds majority required for ratification. According to Kennedy himself, in speaking of the mail received by the White House, while the subject of the test ban treaty was not as popular as requests to the Kennedy family for money, the majority of those who did write in about the treaty opposed it.

Aware of all this, Kennedy was under no delusions about the work that would be needed to get the treaty passed. To get the effort underway, on August 7th, 1963 in the Cabinet Room at the White House, he met with a number of government officials and influential private citizens to brief them on the task at hand. Among those officials in attendance were National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy, State Department officials Lawrence F. O’Brien and Frederick G. Dutton and Adrian S. Fisher of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. Counted in the private sector at the meeting were, besides Norman Cousins, former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations and former chief U.S. representative in the test ban negotiations, James J. Wadsworth, President of the United Auto Workers of America, Walter Reuther and former Eisenhower administration Secretary of the Department of Health Education and Welfare, Marian B. Folsom.

Kennedy told those at the meeting that he placed the highest importance on the ratification fight for the limited test ban treaty. In “The Improbable Triumvirate” Norman Cousins relates that Kennedy told them that to get two thirds of the Senate behind anything was a most difficult undertaking, but to get it on a controversial treaty like the limited test ban would be a miracle. He said he could name fifteen senators who would probably vote against anything linked to President Kennedy’s name—“and that not all of them are Republicans.”

Kennedy, of course, was a Democrat.

It was clear from what Kennedy was saying that if a vote were held right then the Senate test ban treaty ratification would fail miserably. Most senators, Kennedy said, had not made any public statements supporting the test ban and that Congressional mail was running 15 to 1 against the measure. Kennedy concluded his talk to the group by saying:

“My guess is that the mail to the White House and to the Congress against any nuclear test ban will increase. The opponents to any ban are going to try and snow us. I’m not going to underestimate the size of the opposition or the wallop they pack. They know that all they need to knock out the treaty is a handful of votes. / So I thank you for taking on a very tough job. You must not hesitate to use me in any situation where you think I can help. If there’s any person or organization you want me to communicate with personally, I’ll do it. I want you to stay in close touch with me. I’d like to receive regular reports on your efforts and to know of problems as they develop. Now, I’d like to hear about your plan of action.”

Being already familiar with the all of the information on the test ban treaty as well as public awareness on the subject as result of his work with SANE, Norman Cousins responded to the President on behalf of the group. He told Kennedy of a broader coalition that had been formed to mount a national campaign to get the limited test ban treaty passed in the Senate. This coalition was called the “Ad Hoc [6] Committee for a Nuclear Test Ban” and was comprised of major leaders of business, labor, religion, finance, the arts and academia from all over the country. Cousins then briefed the President on the plan for generating popular support for the test ban treaty utilizing full page national advertisements, materials for television debates, forums and discussion programs, and materials for news weeklies and magazines. Cousins also informed Kennedy about the vital role that SANE had played in generating public awareness about the dangers of nuclear testing and the need for a test ban. Kennedy asked for more information about SANE and Cousins briefed him on the group’s history starting with its formation in 1958. While SANE had been effective as far as it went, it was very clear that now a group was needed exclusively dedicated to getting the limited test ban treaty passed, and thus the “Ad Hoc Committee for a Nuclear Test Ban” was created.

After getting the information from Cousins, Kennedy made several suggestions as to additional religious and business leaders to be contacted and expressed his own willingness to assist in getting them on board.

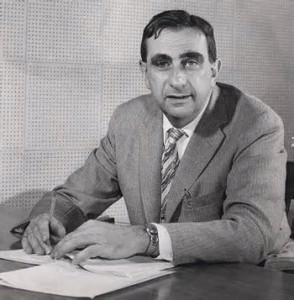

The discussion then turned to where the opposition to the treaty was expected to come from, which centered upon two main sources; nuclear scientists and the military. One of the principal nuclear scientists opposing the treaty was a man named Dr. Edward Teller. Teller immigrated to the U.S. from Hungary in the 1930’s and was involved early on in the U.S. World War II effort to create an atomic bomb, known to history as The Manhattan Project. Following the war he was one of the principal scientists involved in developing a hydrogen bomb for the U.S. and has come to be known as “the father of the H bomb” as a result. During the Cold War he was an ardent advocate of the need for a strong U.S. nuclear arsenal and the right to atmospheric testing to continue to develop and improve nuclear weapons. It is widely thought that when Stanley Kubrick [7]created his Cold War black comedy “Dr. Strangelove” he used Teller as the inspiration for the psychotic scientist in the film. Prominent in the military as opposing the test ban was Chief of the Strategic Air Command, General Tommy Power who was supported in his views by Air Force Chief of Staff, General Curtis Lemay. These men wielded considerable power and influence in the defense industry and on Capitol Hill, and JFK, Cousins and the rest in the meeting knew they faced a big challenge in getting the limited test ban treaty passed.

For the next seven weeks debate over the treaty dominated the news. Cousins and his group supporting the treaty got much more editorial support in newspapers and magazines than they initially expected, but their opponents had also marshaled considerable support. Cousins himself was involved in televised debates with Dr. Teller several times but feared that Teller’s reputation as “the father of the H bomb” lent his arguments in favor of voting down the treaty more authority. Ultimately Cousins and his Ad Hoc group were able to counter Teller’s arguments with scientific arguments of their own from numbers of physicists and scientists who stood up in favor of the treaty.

Things finally came to a head in hearings before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to consider ratifying the treaty. Testifying against the test ban were Dr. Teller and General Power. Countering them in favor of the treaty were Kennedy cabinet officials, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara as well as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor. Norman Cousins also testified using the inside knowledge he had gained from his trips to see Khrushchev in the Soviet Union as to why the Soviets would want such a treaty.

Several days before the Limited Test Ban Treaty went to a vote in the Senate it became apparent to Cousins and the rest of the committee that things had swung in their favor and that they had garnered the necessary votes to get the treaty passed. Nevertheless, following JFK’s advice, they took nothing for granted and continued to campaign hard for popular support and Senate approval.

On September 24th, 1963, by a vote of 80 to 19, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and Kennedy signed it as President on Oct 7. Due to the efforts of a Catholic Pope in the last months of his life, the journalist he had selected to help him, and two world leaders who both had been seared by how close they had brought the world to nuclear annihilation; the first major step of its kind, to limit the use and development of nuclear weapons, had been taken.

The importance of this accomplishment to President Kennedy cannot be overstated. The climate created by the treaty, he thought, made possible other agreements and steps in the direction of peace. As Norman Cousins states in his book, “The Improbable Triumvirate”:

“During the summer and early fall of 1963 President Kennedy carefully laid the groundwork for pursuing initiatives in all these directions (toward peace). Those who worked closely with him reported he didn’t minimize the difficulties or the complications, but neither did he undervalue or under estimate the size and reality of the hopeful prospects that seemed to open out before the United States and the world. This optimism, in fact, was reflected in his last public speech in Dallas (which was never delivered), just before the assassination.”

Just a few days after JFK signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, on October 11th, 1963, he had issued National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 263, which formalized his intent to withdraw from Vietnam; ordering 1000 troops home by the end of 1963, and all troops home by 1965.

Six weeks later, on November 22, 1963, he was shot dead in Dallas, Texas.

_______________________

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] Please see “JFK and the Road to Dallas: ‘Peace Speech’ at American University” earlier in this series.

[2] Izvsetia is a long-running high-circulation daily broadsheet newspaper in Russia. It was a newspaper of record in the Soviet Union from 1917 until the dissolution of the USSR in 1991. The word literally means “delivered messages”.

[3] Please see “JFK and the Road to Dallas: ‘Peace Speech’ at American University” earlier in this series.

[4] Please see “JFK and the Road to Dallas: ‘Peace Speech’ at American University” earlier in this series.

[5] For the whole story of the Laotian crisis please see two earlier articles in this “JFK and the Road to Dallas” series. The first is “The Crisis in Laos” and the second is “Laos: The ‘Vietnam’ That Never Was’”

[6] “Ad Hoc” simply means that whatever the term is being applied to is being done in response to a specific situation or problem, in this case the problem of getting the limited test ban treaty passed.

[7] Stanley Kubrick is a legendary American director of feature films as well as a screen writer and cinematographer. Among the films he is known for, besides “Dr. Strangelove”, are “A Clockwork Orange”, “Spartacus”, “The Shining” and “2001: A Space Odyssey”. Kubrick died in 1999.

One Response