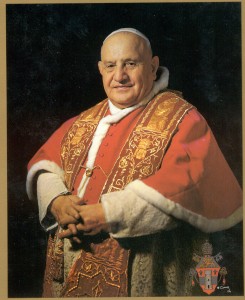

Note: Having delivered Pope John’s “Pacem In Terris” encyclical to Nikita Khrushchev and gotten his agreement and willingness to sidestep the misunderstanding on inspections and make a new start in the Test Ban talks, Norman Cousins’ second mission to the Soviet Union as the Pope’s peace emissary was effectively and successfully completed. Before leaving Khrushchev, however, Cousins and the Soviet leader engaged in a lively conversation covering a number of subjects…I am including a summary of this conversation in this series because it provides much insight into Nikita Khrushchev as a man and a leader as well as his humanity and his paradoxes…here is “Improbable Peace Makers” Part IV….MA

____________________________________

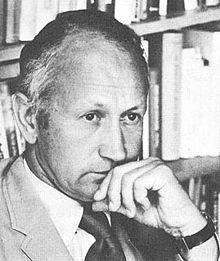

In the early ‘60s Cold War era many people in the United States considered the Soviet Union to be their implacable enemy. It was an impression formed chiefly by the information they gleaned from the media in the United States, whether TV, radio or newspapers. In his lectures and discussions with people in America during this period, Norman Cousins, a long time peace activist as well as journalist, would be frequently asked how the U.S. could ever attain a durable peace with the Soviet Union when Nikita Khrushchev had openly stated that he intended to “bury” the United States.[1] On his second trip to the Soviet Union as the peace emissary of Pope John XXIII, in his conversation with Khrushchev, Cousins asked him how he would comment on this impression that many Americans had. In response, the Soviet Premier stated that he did not mean that he or his nation would bury the United States, but that history would. He went on to say that he had no intention of murdering 200 million Americans, but that the capitalist system was doomed and that it would be the American workers themselves who would overthrow it in the end.

The two men then engaged in a mild debate, with Cousins pointing out data to Khrushchev demonstrating that the conditions of working men in the U.S. were improving drastically, something neither Marx nor Lenin had anticipated happening. Khrushchev responded by saying that Marx would be happy to hear that and would view it as evidence that he was correct in his predictions. The Chairman then commented on the destructive impact TV and degraded programming was having on American youth. Cousins acknowledged the point but then countered with all of the positive aspects of television in America, all the educational programming that was being done and the good effects it was creating.

The conversation continued in this vein for some minutes, with the Chairman expressing his critical views and observations of American capitalism and culture and Cousins, while acknowledging rightness in some of what Khrushchev was pointing out, countering with data which demonstrated a more positive view of America.

As their “off the record” discussion wound down, Cousins asked Khrushchev if, with all the criticism he was receiving from his own nation and allies and the misunderstandings and disappointments on the Test Ban Treaty, he was discouraged about the prospects for peaceful coexistence with the West. The Soviet leader responded that he hoped that the terrible drift to war could be ended and that the United States and Soviet Union could find some way to live in peace. He then, however, re-iterated his earlier statement that the next move in this regard was up to the United States and specifically Kennedy. Despite his upset as regards the Test Ban negotiations, Khrushchev told his guest that he had high regard for JFK and asked that Cousins relay his greetings to the President and Mrs. Kennedy. He also asked Cousins to express to Pope John his concerns over the Pope’s health and to convey his best wishes.

As he spoke Khrushchev was holding in his hand a medallion that had been forwarded to him by Cousins as a personal gift from Pope John following their meeting in December. With regard to the gift Khrushchev commented:

“I appreciate very much the Pope’s personal medallion you sent me. I keep it on my desk at all times. When Party functionaries come to see me, I play with it rather ostentatiously. If they don’t ask me what it is right away, I continue to let it get in the way of conversation, even allowing it to slip through my fingers and to fall on the floor, so that they have to watch out for their toes. Inevitably, I am asked to explain this large engraved disc. ‘Oh,’ I say, ‘it’s only a medal from the Pope…’”

Clearly enjoying his story, Khrushchev chuckled. Thinking this might be a good time for one last question; Cousins asked the Premier if he could change the subject, to which Khrushchev quickly assented. Cousins then posed the question:

“What would you say your principal achievement has been during your years in office?”

Khrushchev replied that he had two achievements in mind instead of just one.

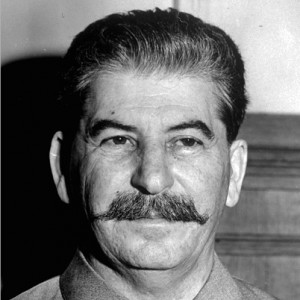

“The first,” he said, “was telling the people the truth about Stalin.[2] There was a chance, I thought, that if we understood what really happened, it might not happen again. Anyway, we could not go forward as a nation unless we got the poison of Stalin out of our system. He did some good things, to be sure, and I have acknowledged them. But he was an insane tyrant and he held back our country for many years. The second thing I am proud of is that it will not be necessary for my successors to shoot me when the time comes for me to leave this office. So my second achievement is very much like the first: I think I have made it possible to have an orderly transfer of authority—not just for the men who replace me but for the men who will replace them.”

Cousins then asked the Chairman if he viewed the discussions he’d had with Kennedy and Eisenhower before him, as historic first steps in a new foreign policy of reconciliation with the West.

“You’re making some good suggestions for my memoirs,” Khrushchev responded light heartedly. He then once again referenced Stalin: “One of Stalin’s great mistakes was to isolate the Soviet Union from the rest of the world. We need friends. We have mutual interests with the United States. These two great countries would be very stupid if they ignored these mutual interests. They also have serious differences. But no one need worry that these differences will be glossed over. There are people in each country who make a career out of the differences. But someone has to speak also of the serious mutual interests. I have tried to talk about them.”

At that moment Cousins’ daughters, who had been swimming in the Chairman’s magnificent swimming pool, approached and the conversation of the two men came to an end. His mission complete, Cousins thanked Khrushchev for being so generous with his time and for his hospitality. He and his daughters then left the Premier to return to Moscow and from there back home. When he got back to the United States Cousins would need to report to the President on the results of his trip. Upon doing so he would find that he had one more important role to play in the unfolding drama that promised to end the Cold War.

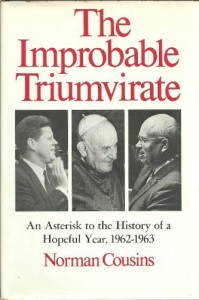

It is obvious from his book “The Improbable Triumvirate” that Nikita Khrushchev made quite an impression on Norman Cousins. He states that to him Khrushchev did not fit the image one might have of a powerful political leader and that there was nothing exalted about the man. While Khrushchev gave the impression of being gregarious, Cousins sensed a lonely quality about him. He also saw that Khrushchev was capable of, what Cousins termed, “sustained and sequential thought,” and that he made time in his life to do this, particularly when the situations he had to handle demanded it. Cousins observed Khrushchev to be a humble man who did nothing to hide his peasant upbringing, yet also a man who would wear expensive clothes and jewelry. Though his peasant upbringing might indicate an unrefined man, Cousins found that Khrushchev often exhibited great “gentility, kindliness and courtesy.” In summing up the Soviet leader in his book Norman Cousins states the following about him:

“I could reflect that if one of the persistent characteristics of prominent leaders in history was a large assortment of paradoxes—and if it is true that a man comes to life in his paradoxes—then it was clear that Nikita Khrushchev was a full-sized leader and one of the substantial figures of the twentieth century.”

____________________________

To be continued…

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] In November of 1956 while addressing Western ambassadors at a reception at the Polish embassy in Moscow Khrushchev delivered a famous speech in which he was widely quoted by U.S. media as saying “ We will bury you!” The impression this created on many Americans was that Khrushchev and the Soviet Union intended to destroy them. I well remember, even as a young child, feeling clearly threatened by what our media reported him as saying. As it turns out, as can be seen from the above, that is not exactly what he meant.

[2] Joseph Stalin: Soviet Leader who assumed power after Lenin’s death in 1924 and who led the Soviet Union for the next 3 decades. He literally forced the country from a mostly agrarian economy into an industrial and military power but did so at vast expense to the environment and people of Russia, many of whom were imprisoned or killed in Stalin’s purges and programs. It is this aspect of Stalin’s rule that Khrushchev is referring to in calling him “an insane tyrant.” Stalin died in 1953 after which Khrushchev came to power.