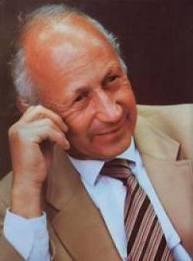

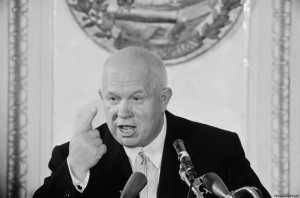

Note: As 1962 merged into 1963 John Kennedy was already well into the last year of his life. With Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev he had successfully negotiated a solution to the Cuban Missile Crisis in late October of 1962, while one more time withstanding the efforts of his intelligence and military people to commit the country to war. His handling of the missile crisis continued a pattern for JFK. Starting with the situation in Laos and the Bay of Pigs disaster in the spring of 1961 on through the Berlin crisis later that year, continuing with the military/CIA efforts to get him to commit combat troops to Vietnam, and on up to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, every step of the way JFK refused to go to war. Never, however, had things come as close to disaster as with the Cuban crisis. With its successful resolution the relief of the whole world was palpable. The coming year of 1963 was looked to with hope that at long last the United States and Soviet Union could end the arms race and the Cold War and find a way to peacefully co-exist. Adding to this hope was the fact that a new player had entered the world political arena; the leader of the Roman Catholic Church, Pope John XXIII. As noted in Part I of this series, he had used his influence correctly and successfully to help resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis. Now he had bigger things in mind. Knowing he was dying of stomach cancer the Pope had resolved to do all he could with the time he had left to bring freedom from the fear of nuclear war and thus real peace to the peoples of Earth. Through his handpicked intermediary, an American named Norman Cousins, he initiated a dialog with Nikita Khrushchev and John Kennedy that set in motion a remarkable chain of events and breakthroughs that promised to accomplish exactly what the Pope intended. Here is Part II of the whole story, one I call “Improbable Peace Makers” …MA

(For best understanding Part I of Improbable Peace Makers, linked here, should be read first)

__________________________________

Norman Cousins held the telephone to his ear and listened in a state of shocked disbelief. The Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin, was on the line and was telling him of a just published newspaper article with the headline: “BISHOP TELLS OF RED TORTURE”. The article referenced the recent release from Soviet prison of Archbishop Josyf Slipyj and the supposed mistreatment he was subjected to while there. A few weeks earlier Cousins had negotiated with Premier Khrushchev for the Archbishop’s release on behalf of Pope John XXIII. Khrushchev had been reluctant to do so because he feared the possibility of what was now occurring, a propaganda attack on the Soviet Union. Cousins had told him then that the Pope intended no such action and that he merely wanted his old friend, Archbishop Slipyj, to be able to live out his last years in peace while pursuing his life’s purpose.

Cousins assured Dobrynin that he knew the Pope had acted in good faith and said he would call the Vatican himself to see what he could find out. On reaching his contacts in Rome, Cousins found they were as shocked as he was. Archbishop Slipyj, they told him, despite literally hundreds of requests for interviews and statements, had spoken to no reporters and there was no way the story was real. Further, they were distraught because now this incident would be a barrier to obtaining the release of other Catholic clergymen held by the Soviets. His Vatican contacts told Cousins that they would do all they could to correct the fabrication, and would have the Vatican newspaper carry a front page statement quoting both Pope John and Archbishop Slipyj that repudiated the false newspaper statements. Cousins phoned Ambassador Dobrynin and informed him of what he learned from his contacts in Rome and the actions they were taking to correct the false articles. He also wrote a personal letter to Khrushchev assuring him that there had been no breach of faith and that Archbishop Slipyj had spoken to no reporters; and that he hoped the Premier understood that.

Despite these actions taken by himself and the Vatican, Cousins knew the damage had been done. Confirming this was the fact that he received no reply from his letter to Khrushchev, or any further communication from Ambassador Dobrynin for a number of months. At the same time, as the weeks of January and February 1963 flashed by, it was apparent that the once hopeful prospects for improved relations between the two superpowers were waning. A number of factors contributed to this. In the Soviet Union Khrushchev was under heavy pressure from Communist Chinese propaganda claiming that he had betrayed their Marxist-Leninist principles when he pulled the missiles out of Cuba. The United States, the Chinese maintained, was bluffing with regard to Cuba, and that when Khrushchev gave in he was capitulating to a “paper tiger”. He also was dealing with similar pressures from people in his own government and military.

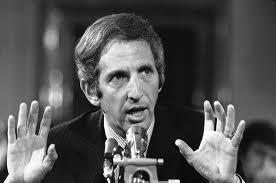

As for Kennedy, he was having difficulties with the hard line element within his own government as well. Immediately after the missile crisis was over Kennedy had asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to come to the Oval Office so he could thank them for their service during the crisis. Far from being happy that the world had avoided nuclear war, Air Force Chief of Staff General Curtis LeMay used the opportunity to tell Kennedy that he thought the way the missile crisis was solved represented the “…greatest defeat in our history,” and that the United States “should invade today.” Many in the upper ranks of the military felt the same. Unique insight to this is provided by former defense analyst Daniel Ellsberg, who was consulting with Air Force generals and officers on nuclear strategy at the exact point in time the missile crisis ended. Ellsberg, who would become famous for leaking the Pentagon Papers in 1971, states that following Kennedy’s settlement of the crisis, “there was virtually a coup atmosphere in Pentagon circles…it was a mood of hatred and rage. The atmosphere was poisonous…”

Also infuriated by the way the crisis ended was the CIA. To them it signaled the end, not only of Operation Mongoose [1] and its related activities, but of even any notion of overthrowing Castro. The anti-Castro Cubans supported by the CIA were equally upset. At the peak of the crisis it looked for sure that the U.S. would finally invade Cuba and oust Castro, and then the situation suddenly resolved in the worst way possible for them; a promise from JFK never to invade. To many of them Kennedy’s actions were treasonous. Never a bunch to accept something as insignificant, to them, as presidential control or directives, the CIA’s David Atlee Phillips and a group of Cuban exiles he directed called Alpha 66 staged a series of attacks on Soviet ships in Cuban waters in March of 1963. As stated later by Alpha 66 leader Antonio Veciana the whole point of the attacks was “to publicly embarrass Kennedy and force him to move against Castro.” The attacks succeeded in creating angry protests from Khrushchev which ultimately resulted in JFK arresting the Alpha 66 Cuban leaders and confining them to Miami.

From the above one can see that in the late ’62 to early ’63 period following the missile crisis both Kennedy and Khrushchev were dealing with much counter intention from within their own governments and alliances, and were therefore walking a perilous line. Unless there could be a significant breakthrough for peace sometime soon, it was possible both could be overwhelmed by the hard line elements within their respective governments. The hopeful window brought about through the successful efforts of both leaders to avoid nuclear war during the Cuban crisis, was closing.

Compounding the situation was the impasse that had developed in the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty negotiations between the U. S. and the Soviet Union. The two nations had been engaged in talks off and on since the mid ‘50s to try to reach agreement on limiting or eliminating nuclear testing in the atmosphere, the sea and underground. By the mid ‘50s enough scientific data had been gathered as to the danger of nuclear fallout and radiation that it was obvious that continuing nuclear bomb tests in the atmosphere or sea was harmful and threatening to life beyond the blast zone. Citizens of the world had become aware of this data and demand was building from many quarters to end the testing. For a short period in 1960 it looked like the Test Ban Treaty might become a reality as President Dwight Eisenhower and Premier Khrushchev had embarked on their “Crusade for Peace.” Their hopes had been shattered when Francis Gary Powers was shot or forced down while piloting a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union in the spring of 1960.[2] The incident destroyed the trust between Eisenhower and Khrushchev, and destroyed as well the possibility of a Test Ban Treaty while Eisenhower was in office.

With the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis the hopes for a Test Ban Treaty were reinvigorated and talks had resumed, first in New York in mid January of 1963, and later in Geneva, Switzerland. By mid March, however, the talks had stalled completely. The disagreement centered on the perceived need by the United States for inspections to verify that the Soviets were not engaging in underground nuclear testing. (atmospheric or sea tests were not at issue as they were much more observable than underground tests.) The Soviet view was that advanced enough instrumentation existed to allow the U.S to monitor their compliance from outside the borders of the Soviet Union. The U.S negotiators hung up on this point, however, stating that it was very difficult to tell the difference between an underground nuclear explosion and an ordinary seismic event on the monitoring instruments. Because of this they insisted on the need for inspections within the Soviet Union. The Soviet negotiators suspected the underlying reason for the U.S. insistence on inspections was really espionage, and so they wanted no inspections. Finally, the negotiators for both countries settled on allowing 3 inspections annually to verify compliance to there being no underground testing. The Russian representatives relayed this to Khrushchev who then persuaded his Council of Ministers to accept it. Khrushchev’s and his Council’s approval of the three inspections was then forwarded to their negotiators, only to then find that the U.S. was now demanding eight inspections. The U.S. negotiators could not understand how the Russians had duplicated three inspections, claiming they were misunderstood. The Soviet negotiators could not understand why the U.S. was now saying eight, and felt betrayed by this perceived shift in the U.S. position. Khrushchev felt like an idiot for having pushed so hard to get the three inspections approved and now suspected that the U.S. motive really was espionage.

Meanwhile, the hard line people in the governments and military of both nations, citing national security concerns, were pushing hard on both Kennedy and Khrushchev for more nuclear testing. The United States, the Russians claimed, had a distinct advantage in that they had been able to conduct more tests than the Soviet Union, and they were insisting that the Soviets needed to close this gap. U.S. scientists and military were saying that they needed to do more atmospheric testing to assist in the development of an anti-missile missile. With the stalled Test Ban negotiations, and the pressure building to continue testing, it seemed to many that the all the good feeling and apparent progress accomplished since the Cuban crisis was evaporating. A distinct Cold War chill was returning to the air.

In the Vatican Pope John was also feeling the developing chill, and despite his worsening physical condition he wasted no time in doing something about it. In mid March he sent his representative, Father Felix Morlion, to New York to visit Norman Cousins to once again ask him to represent the Pope in a meeting with Nikita Khrushchev. Father Morlion told Cousins that the Pope was very concerned about the recent deterioration of the prospects for peace; so concerned that besides requesting that Cousins go on this mission he was also in the process of writing a major encyclical[3] on the subject of world peace that would be published in a few weeks. Pope John’s peace paper, Father Morlion said, would be a document of major historical importance. The Pope also hoped that Cousins would be willing to explore with Khrushchev the possibility of releasing other members of the Catholic clergy held in Soviet prisons. Cousins had been in poor health since his prior trip to Moscow in December and was reluctant to take on this new mission. Not wanting to impose on Cousins’ health, Father Morlion nevertheless impressed upon him the need for continuity in these missions.

Understanding this, Cousins checked with the U.S. State Dept to see if another trip to the Soviet Union would serve any useful purpose from the viewpoint of the United States. About two weeks after Father Morlion’s request to him, Cousins met with Secretary of State Dean Rusk in Washington. Rusk told Cousins that the impasse in the Test Ban Treaty negotiations over the issue of the number of inspections was simply a misunderstanding, and that there was no intent to mislead the Russians. He also said, however, that it would be impossible to get the Senate to pass the treaty with anything less than eight inspections, and that the negotiations were in danger of bogging down completely. Despite this, Rusk felt that another Cousins trip to Russia could serve a useful purpose. Should he meet with Khrushchev, Rusk said, Cousins could bear witness to the good faith of the United States as regards the negotiations. Rusk also thought that Cousins could suggest to Khrushchev that the negotiators continue working to resolve the other five or six issues needing handling and leave the inspections issue to Kennedy and Khrushchev to settle. Rusk authorized Cousins to tell Khrushchev that President Kennedy was fully confident that he and the Soviet leader, negotiating in good faith, could rapidly solve the matter of inspections.

Following his meeting with Secretary Rusk, Cousins met with Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin and asked him to send a request to Premier Khrushchev asking for another meeting. Norman Cousins had made up his mind. He would make another trip to the Soviet Union in search of peace.

To be continued…

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] For a description of “Operation Mongoose” please see “JFK and the Road to Dallas: The Cuban Missile Crisis Part I” earlier in this series (linked here)

[2] The Francis Gary Powers U-2 incident is discussed in “JFK and the Road to Dallas: The Missiles of Cuba-Prelude to a Crisis” earlier in this series (linked here)

[3] Encyclical: in the Roman Catholic Church, a formal statement or letter issued by the pope to bishops, often on matters of doctrine. In this case Pope John intended a much larger audience for his letter–the people and government leaders of the world.

4 Responses

Good article.

Thanks, Stan! Hope you are well. L M

There must be so much background activity that we are still unaware of concerning the political events of this period!

The intentional publishing of a ant-USSR smear article with the release of Slipyj clearly points to secret forces at work who had access to media outlets. Who knows what other lies they were spreading to the various public players?

So true, Larry! In my research in this period I never did find who was behind the Black PR attack on the Soviet Union vis a vis the release of Slipyj, though I do have my suspicions, with CIA at the top of the culprit list. Thanks for reading and commenting. MA