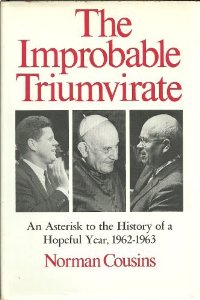

Note: In 1972 a man named Norman Cousins wrote a book entitled “The Improbable Triumvirate: An Asterisk to the History of a Hopeful Year, 1962-1963.” The book chronicles how Pope John XXIII, using Cousins as an intermediary, was able to assist in establishing a dialogue between John Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev in the months following the Cuban Missile Crisis and thereby assist the two leaders in their efforts to resolve the Cold War. At the time, late 1962, Pope John only had a few months to live as he was dying of stomach cancer. Norman Cousins in 1962 was the editor of “Saturday Review”, a magazine he had run for the prior 20 years. He was also an ardent proponent of world peace and nuclear disarmament and had founded a group called the “National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy” (SANE). Though Cousins was a well known journalist, it is a bit much to expect that he would become the peace emissary of Pope John XXIII to the world’s two most powerful leaders at this critical time in history. Just how that occurred and the ultimate effect it created is a fascinating story. Borrowing a bit from Cousins, I call it “Improbable Peace Makers”. Here it is…MA

__________________________________

In late October of 1962 Norman Cousins and his associates were holding a very interesting meeting. They had managed to bring together a group of leading Soviet scientists, writers and educators, and a parallel group from the United States, for the purpose of engaging in honest dialogue on the subject of world peace. The idea for such meetings, which are now referred to as the Dartmouth Conference Series because the first meeting was held at Dartmouth College (1960), had originated with President Dwight Eisenhower in 1959. At that time Eisenhower asked Cousins if he would be willing to go to the Soviet Union and see if it would be possible to arrange a series of meetings between prominent citizens of both nations. Eisenhower felt that the diplomatic process between the two nations could be aided by such meetings as the participants of these informal citizen conferences could speak their minds in an unrestricted way, the hope being that such dialogue could open the door to more effective formal negotiations between the two nations.

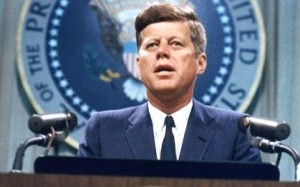

The October, 1962 meeting was being held at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. On the very first night of their conference, instead of their planned activities, they all sat around a TV watching President Kennedy make his announcement to the American people that the Russians had placed nuclear missile sites in Cuba and that the United States, in response, was initiating a blockade. The group was thus directly and starkly confronted with the reason for their meeting and they all agreed the conference should continue despite the on-going crisis.

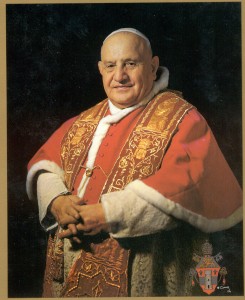

A couple of days into the conference and against the backdrop of the continuing missile crisis, the Russian and American delegates at Andover received a special visitor. His name was Father Felix Morlion and he had been sent to the conference from the Vatican as Pope John XXIII’s personal envoy. Cousins had first met Father Morlion in March of 1962 in New York. The Father was the president and founder of Pro Deo University in Rome; a school known for its international and interreligious curriculum. He had come to New York and Cousins in particular to seek support for his university. Cousins spent an afternoon and evening with Father Morlion during which their discussion turned to the subject of Pope John. The Father told Cousins that the Pope wanted to assist in defusing the Cold War tensions between the U.S. and Russia and help to bring about an international climate conducive to peace. “You must believe me,” Father Morlion told Cousins, “when I tell you that dramatic ideas are shaping up and all the world will come to acclaim and love this gentle man, Pope John. He is not arbitrary or fixed. He has a profound respect for people of all faiths. He wants to help save the peace.” It would be at this Andover conference that the “dramatic ideas” of Pope John spoken of by Father Morlion would start to manifest in the world. The Father posed a question to the group: “Might a papal intervention in the Cuban Crisis—even if only in the form of an appeal for greater responsibility—serve an important purpose? Would a proposal to both nations be acceptable that called for a withdrawal both of military shipping and the blockade?”

Understanding the importance of the Pope’s offer, Cousins phoned the White House and spoke with the President’s advisor and speech writer Ted Sorensen who then consulted with JFK. The response to Cousins was that, while the President welcomed the Pope’s offer, he also wanted Pope John to realize that the central issue was not the military shipping but the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba and that those missiles had to be removed; on that there could be no compromise. A member of the Soviet delegation forwarded the Pope’s offer to Moscow. A positive response from Khrushchev was received that indicated the Soviets would respond favorably to such an offer. Though it was clear that the Soviet willingness did not completely match what the U.S. required, Father Morlion relayed the American and Soviet responses to the Vatican.

The next day, October 25, 1962, Pope John issued his now famous plea for moral responsibility by world leaders in the handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Directed primarily at the U.S. and Soviet Union and delivered directly to their embassies, the Pope’s words were headlined around the world; even in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. In the plea the Pope stated:

“We implore all rulers not to remain deaf to the cry of humanity for peace. That they do all that is in their power to save peace. They will thus spare the world from the horrors of a war whose terrifying consequences no one can predict. That they continue discussions, as this loyal and open behavior has great value as a witness of everyone’s conscience and before history. Promoting, favoring, accepting conversations, at all levels and at any time, is a maxim of wisdom and prudence which attracts the blessings of heaven and earth.”

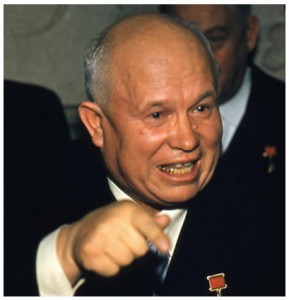

Three days later Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for Kennedy’s pledge that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis was over. Years later in recalling the crisis and with regard to Pope John’s plea for peace, Khrushchev said that at the time, “This message was the only gleam of hope.”

One other important point was brought up at the Andover meeting of Soviet and American scientists, writers and educators. Father Morlion wanted to know if the Soviet Union would be open to further communications with the Vatican on the subject of peace. Considering the history of Soviet persecution of Catholics and the resultant cool relations between Moscow and Rome, it was a bold proposal. Father Morlion further suggested that Norman Cousins would be an acceptable intermediary for the Pope to represent him in the discussions. Would Cousins, Father Morlion also wanted to know, be acceptable to the Soviets? The Russian delegates said they would forward the suggestion. One month later, in late November, 1962, Cousins received a phone call from Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. Father Morlion’s suggestion had been approved by the Soviets and Khrushchev had invited Cousins to meet with him in Moscow in mid December. The odyssey of Norman Cousins as a global peace maker was about to begin.

On getting word that he had been approved by the Russians as Pope John’s representative and had been invited to visit Khrushchev, Norman Cousins contacted the White House to inform the President of his upcoming trip. As a result JFK arranged to meet with Cousins prior to his departure for Moscow. At this meeting Kennedy gave a message to Cousins that he wanted to ensure was delivered to his counterpart in the Soviet Union. Khrushchev, Kennedy told Cousins, “…will probably say something about his desire to reduce tensions, but will make it appear there’s no reciprocal interest by the United States. It is important that he be corrected on this score. I’m not sure Khrushchev knows this, but I don’t think there’s any man in American politics who’s more eager than I am to put Cold War animosities behind us and get down to the hard business of building friendly relations.” Thus, at the time of his departure to Moscow for his meeting with Nikita Khrushchev, Norman Cousins was as much JFK’s emissary as he was Pope John’s.

On his arrival in Moscow, Cousins became aware of some of the pressures that affected Khrushchev, and in many ways still affected him, as regards the Cuban Missile Crisis. Khrushchev’s supporters told Cousins that the Premier was under great pressure to vindicate what was now being viewed as a policy of coexistence with the United States. There were many in the Communist world, including the Chinese government and officials in Khrushchev’s own government and military, who felt that his withdrawal from Cuba was simply knuckling under and giving in to the United States. With regard to this Khrushchev told Cousins, “The Chinese say I was scared. Of course I was scared. It would have been insane not to have been scared. I was frightened about what could have happened to my country—or your country and all the other countries that would be devastated by a nuclear war. If being frightened meant that I helped avert such insanity then I’m glad I was frightened. One of the problems in the world today is that not enough people are sufficiently frightened by the danger of nuclear war… Anyway, most people are smart enough to understand that it is ridiculous to talk in terms of another war. Pope John understands this. I would like to express my appreciation to him for what he did during the crisis of the Cuban week.”

Cousins and Khrushchev then discussed an issue that Pope John had asked Cousins to take up with the Soviet Premier; the releasing of Catholic Archbishop Josyf Slipyj who had been accused of Nazi collaboration during World War II and imprisoned for 18 years. Despite expressing his admiration for Pope John, Khrushchev was reluctant to release the Archbishop. He felt that releasing him would result in press attacks on the Soviet Union for religious repression and torture and that it might end up worsening Soviet relations with the Vatican. Cousins assured Khrushchev that Pope John would not use Slipyj’s release for propaganda purposes, but the Soviet Premier was clearly not inclined to agree to the Pope’s request.

Cousins felt that he had hit a sore spot with the Russian leader and was about to leave when Khrushchev asked him to stay. He then asked Cousins about how President Kennedy was doing. Cousins responded that the President was in good health and then the two men went on to discuss several other issues, including the prospects for a possible nuclear Test Ban Treaty. During the conversation Cousins took the opportunity to relay to Khrushchev Kennedy’s sentiments about his desire to end the Cold War. In response Khrushchev said, “If that’s the case he won’t find me running second in racing toward that goal.”

On this optimistic note Norman Cousins left the Soviet Union and flew to Rome to report on his Moscow mission to Pope John. Despite the failure to acquire Archbishop Slipyj’s release the Pope was happy with the results. “Much depends now,” he said, “on keeping open and strengthening all possible lines of communication. As you know, I asked the statesmen (during the crisis) to exercise the greatest restraint and to do all that had to be done to reduce the terrible tension. My appeal was given prominent attention inside the Soviet Union. I was glad that this was so. This is a good sign.” The Pope then added, “World peace is mankind’s greatest need. I am old but I will do what I can in the time I have.”

Norman Cousins returned to the United States and a few weeks later, in early January, 1963 he received a phone call from Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin inviting him to lunch at the Soviet embassy in Washington. At their meeting Ambassador Dobrynin informed Cousins that Archbishop Slipyj was about to be released. Khrushchev, Dobrynin said, “…has undertaken this action in the spirit of his conversation with you, in which the importance of strengthening the peace was recognized, and as a manifestation of his high regard for Pope John and the efforts being made by His Holiness in behalf of world peace.”

The feeling of success that Cousins must have enjoyed as he was leaving the Soviet Embassy that day would be short lived. Two days after the Archbishop’s release he got another phone call from Ambassador Dobrynin. The Ambassador read to him a just published newspaper article with the headline: “BISHOP TELLS OF RED TORTURE.” Exactly as predicted by Khrushchev, Slipyj’s release had been used in a propaganda broadside against the Soviet Union.

(to be continued)

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

One Response