Note: In the Foreword to Robert Kennedy’s memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis “Thirteen Days”, written by JFK aide Arthur Schlessinger Jr., insight is provided regarding John Kennedy and the way he managed the crisis situations facing him during the one thousand days he was in office. Schlessinger points out that in 1960 Kennedy had read a book by noted English military analyst Basil Liddel Hart entitled “Deterrent or Defense”. In his book Hart lays out what he considered the best negotiating strategy for dealing with a difficult and dangerous adversary to defuse a confrontation. He describes this as follows: “Keep strong, if possible. In any case, keep cool. Have unlimited patience. Never corner an opponent and always assist him to save his face. Put yourself in his shoes—so as to see things through his eyes. Avoid self-righteousness like the devil—nothing is so self-binding.” Throughout the Missile Crisis time and again JFK displayed these characteristics to keep the situation from degenerating into war. In addition, according to Robert Kennedy in his memoir, shortly before the Cuban Missile Crisis broke, JFK read Barbara Tuchman’s Pulitzer Prize winning book “The Guns of August” about the factors precipitating World War I as well as the strategies and campaigns of the war itself. In her book Tuchman makes the point that the principal parties involved in the war, the English, French, Germans, Austrians and Russians allowed themselves to be overtaken by the rush of events and tumble into war for reasons that were based either on misunderstandings or outright stupidity. They also engaged in military strategies based on outmoded 19th century military technology which resulted in massive casualties in the 20th century combatant armies. “The Guns of August” made a big impression on JFK and he was determined not to, as he put it to his brother during the height of the Crisis, “…follow a course which will allow anyone to write a comparable book about this time, ‘The Missiles of October’. If anyone is around to write after this, they are going to understand that we made every effort to give our adversary room to move. I am not going to push the Russians an inch beyond what is necessary.” As you read what follows in these installments on the Cuban Missile Crisis and as you see just how close we came to nuclear annihilation, you can be thankful that the President of the United States during that crucial time had such a viewpoint. MA

With his decision to use naval blockade as his primary strategic response to the Soviet/Cuban missile threat, JFK kicked into high gear the diplomatic efforts needed to fully inform U.S. allies around the world. Part of this diplomatic effort also involved gaining approval for the blockade from the Organization of American States; a step which would give the strategy the air of legality under international law. Without this approval the blockade could be considered an act of war. (To further distance his strategy from being considered an act of war, JFK chose the term “quarantine” to use when describing the blockade in his public announcements and speeches.) The OAS meeting was not scheduled until Tuesday the 23rd but much work had to be done to ensure it would result in the needed decision to support the blockade. In addition Congress needed to be fully informed of the situation, which due to its partisan nature presented its own unique challenge. A number of Senators, including Richard Russell of Georgia and William Fullbright of Arkansas were extremely critical of the President’s strategy claiming a much stronger military response was warranted. JFK did his best to assure them that the necessary steps were being taken to protect the security of the nation but that he did not think that more extreme military action was required immediately. The blockade option, he told the Senators and Congressmen, afforded the best opportunity to resolve the crisis and get the missiles out peacefully and they retained the option of more extreme military action if necessary. Despite the pressure from Congress JFK held his ground on these points. To prevent the press from leaking the news early to what was still a largely unsuspecting public, Kennedy personally intervened with several newspapers to get them to hold off on publishing anything until after his speech to the country, which was scheduled for Monday evening, October 22nd.

At the same time the military preparations were accelerated as well. Missile crews and sites were placed on high alert status and troops and equipment were rapidly moved to Florida and Georgia and prepared for action. The navy sent 180 ships into the Caribbean and the U.S. base at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba was strengthened and the families of the servicemen stationed there evacuated. The Strategic Air Command was removed from its normal bases and distributed to civilian landing fields to lessen attack vulnerability and the B-52 nuclear bomber force was ordered into the air and kept there around the clock; a new bomber taking flight whenever an already airborne one had to land for rest, fueling or maintenance. By any measure, the period between the time on Saturday afternoon, 20 October when Ex Comm and JFK arrived at the blockade decision and 7PM Monday evening, October 22nd when Kennedy gave his speech to the nation, was whirlwind.

In 1962 the state of television was not even close to what we have today. Cable did not exist, most TVs were black and white and we had only 3 main channels and networks; ABC, NBC and CBS. For his address to the nation JFK had booked all three networks. Starting at 7PM Eastern Time a stunned and worried people were briefed by their President on the situation and the handling the U.S. was implementing. Kennedy spoke for nearly 20 minutes, telling the people that the missiles had been discovered, of the duplicity of the Soviet Union and its leaders regarding them and of the “quarantine” being implemented to stop the shipment of further offensive missiles and weapons to Cuba. In the speech he also stated that the Soviet Union’s reckless action of placing the missiles in Cuba was responsible for pushing the world to the abyss of nuclear war and called upon Premier Khrushchev to abandon the dangerous actions his government had undertaken and to abandon as well its plans of world domination. He pointed out that though we are a peaceful people and do not wish war with the Soviet Union, we could not move forward with the Soviets toward peace in an environment of intimidation and he left no doubt that the quarantine would remain in place until the missiles were removed. He warned the American people that the effort the nation was undertaking would be difficult and dangerous and the path full of hazards and that our national will and patience would be tested. There was even a section of the speech at the end addressed to the Cuban people themselves in an effort to drive a wedge between them and what JFK referred to as their “puppet” leaders who were dominated by a foreign nation.

Kennedy’s broadcast was in many ways a classic Cold War speech in which full responsibility for the missile crisis was laid at the door of the Soviet Union and Castro. While it was true that the Soviet leaders had been duplicitous, nothing was said of the U.S. support of the corrupt dictator Batista which helped set the stage for the Cuban Revolution by which Castro came to power. As well nothing was said about the continuous CIA/Operation Mongoose efforts to depose and/or kill Castro and the infiltration and sabotage Cuba had been subjected to for years, not to mention outright invasion (Bay of Pigs), which forced Castro’s hand at allying himself with the Soviets and bringing the missiles to Cuba. A more balanced view of the situation, which we can afford today, must acknowledge these things. In the Cold War climate of 1962 however, while it is possible JFK may have thought of these things, it would have been political suicide for him to state them, particularly in a situation in which it appeared we had a gun to our heads. The bellicose environment of the times made the handling JFK had chosen that much more dangerous a path to walk, but it was the only one, he felt, that afforded an honest way out of the situation AND avoid a war that could kill millions of Americans and Russians and therefore could not be won. A worried nation went to bed that night uncertain of what the next day would bring or if there would even be another day.

On Tuesday morning, October 23rd, Ex Comm met again to discuss the possible responses to be expected from the Soviet Union and how the U.S would deal with them. The CIA reported that to that point there had been no general Soviet alert made to their armed forces. Regardless, JFK ordered preparations be made for dealing with a potential Soviet blockade of Berlin and the group also discussed how to respond to the possibility that a U-2 or other aircraft might be shot down on reconnaissance flights over Cuba. They agreed that the response to such an event, once the President was informed and approved it, would be to attack and destroy the SAM (surface to air missile) sites in Cuba using jet fighters and bombers. JFK was concerned about two things mainly in this meeting: that the armed forces were ready to respond instantly in the event the country was attacked and that there should be no error or mistake made that would draw the nation into war like those discussed in “The Guns of August”. He was very adamant on both points.

Later that afternoon the Organization of American States passed a resolution approving the Cuban quarantine and at 6PM the Ex Comm group reconvened while JFK prepared the proclamation to commence the blockade starting at 10 AM Wednesday morning. He also composed a letter to Khrushchev that asked him to observe the quarantine that had been legally established by the vote of the OAS. The Ex Comm group went on to establish the rules by which the Soviet ships would be stopped and inspected. Should a ship refuse to stop it was determined that the Navy ships would shoot at the Soviet vessel’s rudder or propeller to disable it and then carry out the inspection. JFK was extremely concerned that during such an incident a “Guns of August” type error might occur and he expressed this concern at the meeting. The possibility was also discussed that they might disable and board a ship carrying nothing more than baby food and how silly and bad that would make them look. They determined, therefore, that they should concentrate on vessels as targets that had a high probability of carrying military equipment. The issue of which ships to stop and how to stop them was a very real problem for Ex Comm and the President as they endeavored to walk the line between getting the missiles out of Cuba and avoiding all out war.

On top of this Khrushchev’s response to Kennedy’s speech had been received and its tone was belligerent. In the letter he accused Kennedy of threatening the Soviet Union with the blockade and insisted that his nation would not submit to it stating that “…the actions of the USA with regard to Cuba are outright banditry or, if you like, the folly of degenerate imperialism”. He further accused the U.S. of pushing the world to the abyss of nuclear war and that should the U.S try to stop Russian ships appropriate defensive measures would be taken; measures of which his nation was fully capable.

As if all of this wasn’t enough, CIA Director John McCone reported that Soviet submarines were now starting to move toward the Caribbean which prompted JFK to order the Navy to give its highest priority to tracking the subs and protecting the U.S vessels in the area. Later that evening, at JFK’s order, Robert Kennedy had a meeting with the Soviet ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin. The purpose of the meeting was to have RFK relay to the Soviets just how serious the situation they had created in Cuba was to the United States and to drive the point home. At the meeting RFK also asked Dobrynin about the assurances Dobrynin had given in September that there were no offensive weapons or missiles in Cuba. RFK stated that the President had relied on those assurances and that now the Soviet betrayal was endangering the world. Dobrynin maintained that he merely reported what he had been told by his government and that as far as he knew officially there still were no Soviet missiles in Cuba.

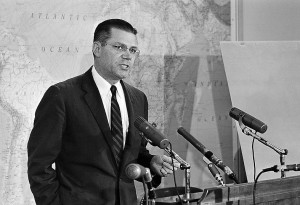

His message delivered, RFK concluded the meeting with Dobrynin and returned to the White House about 10:30 PM that night. The President was in a meeting with an old friend of his, the British Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore, and RFK joined them. At this meeting Ormsby-Gore suggested that the President reduce the blockade line from 800 miles off shore to 500 miles in order to give the Soviets more time to think about their position. The President liked the idea and ordered Robert McNamara to implement it, which he did. Regardless, as the 10 AM Wednesday morning zero hour for starting the blockade drew closer, the Soviet ships on the sea lanes to Cuba showed no signs of slowing down or stopping. No one knew what the next day would bring.

On Wednesday morning JFK made his pronouncement initiating the quarantine. The closest Russian ships still steamed steadily toward the blockade line showing no signs that they intended anything except continuing straight through to Cuba. The moment of truth, in which the Navy would either have to go ahead and stop the ships or back down, was fast approaching. It was the moment most fraught with danger and the one which everyone feared. In addition, at that morning’s Ex Comm meeting, Tuesday’s surveillance film was displayed clearly showing the progress being made on the missile site construction in Cuba. It looked as though the sites would be operational within a few days. Shortly after 10 AM Defense Secretary McNamara announced that the first two Soviet vessels, the Gagarin and the Komiles were a few miles out from the line and would be intercepted within the hour. This was closely followed by a report that a Soviet submarine had been detected and had stationed itself between the two Soviet freighters. The Soviets had just upped the ante. Was it a bluff? Were they preparing to engage for real? At that moment JFK and the entire Ex Comm were faced with a real “Guns of August” situation that could very rapidly spiral out of control. Urged on by two nations who seemed utterly incapable of arriving at any kind of common ground, the whole world had truly arrived at the precipice.

The appearance of the Soviet submarine presented a massive problem that had to be dealt with for the quarantine to continue. Originally JFK had decided to have a Navy cruiser make the first interception of a Soviet vessel but the submarine had changed things. Kennedy now decided that the aircraft carrier Essex would be used supported by helicopters carrying anti-sub equipment. The Essex was to use sonar to signal the sub to surface. If it refused small explosive depth charges were to be employed to force it to the surface. Of course the likelihood was that the sub would not just sit there and be a target for depth charges. Likely it would fire back at the Essex. The President made one last appeal to Robert McNamara, asking him if there wasn’t some other option than having their first exchange be with a Russian submarine. “No”, said McNamara, “there’s too much danger to our ships. There is no alternative. Our commanders have been instructed to avoid hostilities if at all possible, but this is what we must be prepared for, and this is what we must expect.” Fully aware of the implications of the orders he was about to issue, for a long minute the President looked at his brother across the table. Despite all of his precautions and deliberations, JFK sat there with his worst “Guns of August” fears taking form before his very eyes.

Suddenly a messenger burst into the room and handed a note to CIA Director John McCone. Reading from the note, McCone informed JFK and everyone else in the room: “Mr. President, we have a preliminary report which seems to indicate that some of the Russian ships have stopped dead in the water.” A few minutes later McCone had confirmed the report. The twenty closest Soviet ships to the quarantine line had all stopped and many were turning around. JFK quickly got orders to the Essex and the other Navy ships on the scene that none of the Soviet ships were to be stopped or intercepted and no depth charges released at the submarine. If the Soviets had ordered them to turn around he did not want them interfered with in any way. The relief in the room was palpable. About 40 minutes had passed since Kennedy had started the quarantine. They had been the most dangerous 40 minutes in the history of the United States and, indeed, the whole world.

For a few fleeting hours it appeared the worst of the crisis might be over. That afternoon however, the news came that only 14 of the Soviet ships had turned back. A number of tankers had continued toward the line and one of them, the Bucharest had reached the line, identified itself, and because it was a tanker and likely not carrying any armaments JFK had allowed it to pass without boarding and inspection. The Bucharest became something of an issue amongst the hardliners in the Ex Comm group who felt if the quarantine was to be an effective deterrent they actually needed to stop and board some ships. Kennedy knew that at some point this would need to be done but nevertheless allowed the Bucharest to continue on its way to Cuba, stating that he wanted to give Khrushchev more time to consider things and not back him into a corner. Though he let the Bucharest pass, JFK stepped up the over flights of Cuba using low flying jets as well as U-2 spy planes to closely monitor the progress being made on the missile sites. The resulting photos from the over flights on analysis revealed that the work had been stepped up on the sites and was proceeding rapidly. Should the missile sites become operational before a resolution to the crisis could be effected Kennedy’s hand would be forced. He would have to authorize an attack to take out the sites no doubt killing Russians in the process. It would be “The Guns of August” all over again and it began to appear as if the reprieve of Wednesday morning when the Russian ships had stopped and turned around was nothing more than false hope. Another tense night passed.

On Thursday, 25 October, Kennedy responded to Khrushchev’s antagonistic letter of the 23rd stating that in September he had been very plain with the Soviets when he said that should the Soviet Union place offensive missiles or weapons in Cuba it would constitute the gravest of issues to the United States. He pointed out that he had been assured on multiple occasions by the Soviets that this would not happen and that any military assistance to Cuba was defensive in nature. He then went on to say:

“In reliance on these solemn assurances I urged restraint upon those in this country who were urging action in this matter at that time. And then I learned beyond doubt what you have not denied—namely, that all these public assurances were false and that your military people had set out recently to establish military bases in Cuba. I ask you to recognize clearly, Mr. Chairman, that it was not I who issued the first challenge in this case, and that in light of this record these activities in Cuba required the responses I have announced. I repeat my regret that these events should cause a deterioration in our relations. I hope that your Government will take the necessary action to permit a restoration of the earlier situation.”

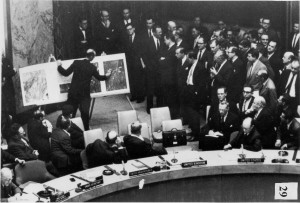

Meanwhile world concern was mounting over the crisis as it was becoming apparent that there was a very real threat of nuclear war. English philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell sent Kennedy a letter taking him to task for what he took as a “war like” attitude assumed by the United States while Secretary General of the United Nations U Thant weighed in proposing that the U.S. lift the quarantine for several weeks in exchange for a Soviet promise to ship no more missiles to Cuba. (Being from Burma the Secretary General had a single name “Thant”, the “U” in front being the Burmese equivalent of “Mr.”) Kennedy, knowing that U Thant’s idea did nothing about the missiles already in Cuba, declined this overture stating that nothing less than the removal of the missiles would suffice to lift the quarantine. It was against this backdrop of mounting world concern and tension that the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson confronted the Soviet UN ambassador Valerian Zorin at the historic UN Security Council meeting during which Stevenson displayed some of the surveillance photos of the Soviet missile sites in Cuba.

To that point the U.S./Soviet crisis had been on the order of a high stakes “Yes you did!”—“No I didn’t” type dispute. No hard evidence one way or the other had been presented to the world. United States duplicity in both the Bay of Pigs debacle in 1961 as well as the Gary Powers U-2 incident in 1960 had been made plainly evident to the world and it would be no understatement to say that many national leaders had doubt that the U.S. was being honest now. All of that changed when Stevenson confronted Zorin, who did not know apparently that the U.S. was prepared to present the photos. A short portion of the exchange between the two ambassadors during the U.N. Security Council meeting follows:

Stevenson: “…All right, sir, let me ask you one simple question. Do you, Ambassador Zorin, deny that the U.S.S.R. has placed and is placing medium and intermediate range missiles and sites in Cuba? Yes or no? Don’t wait for the translation, yes or no?”

Zorin: “I am not in an American courtroom, sir, and therefore I do not wish to answer a question put to me in the fashion in which a prosecutor puts questions. In due course, sir, you will have your answer.”

Stevenson: “You are in the court of world opinion right now, and you can answer yes or no. You have denied that they exist, and I want to know if I have understood you correctly.”

Zorin: “Continue with your statement. You will have your answer in due course.”

Stevenson: “I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over, if that’s your decision. And I am also prepared to present the evidence in this room.”

Stevenson then hauled out large charts displaying the photos showing the missiles and sites for everyone at the U.N to see. The photos and Stevenson’s handling of them at the U.N were a PR coup for JFK and the U.S. as it became clearly evident that in this instance it was the Soviets who were lying.

Later in the day another vessel reached the quarantine line, this time an East German passenger ship carrying 1500 people. Again the hard line faction of Ex Comm wanted the ship stopped and boarded but JFK, fearful of an incident occurring on a ship with so many people on board, again declined and allowed the ship to pass. Finally at 7AM on Friday, October 26th the first ship arriving at the line was stopped and at 8 AM boarded. The ship was the Marucla; an American built and Panamanian owned vessel that was registered in Lebanon. JFK had personally selected the Marucla as the first ship to be stopped as it was not even a Russian ship and therefore represented no threat to them. Stopping and inspecting it, however, would communicate to the Soviets that the U.S. was serious about enforcing the quarantine.

Despite Kennedy’s patience and the carefulness with which he was proceeding the Soviets continued to press forward with the construction of the missile sites. Time was getting very short. It began to appear to everyone in Ex Comm, including the President, that the effort to bring limited pressure and negotiate with the Soviets was failing. All in Ex Comm were in agreement; the U.S. could not allow those missile sites to become operational. Claiming that the missiles in Cuba afforded the Soviet Union a “first strike” capability that could kill millions of Americans as well as significantly degrade U.S. retaliatory options, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were insisting on air strikes to take them out followed by invasion. To make things worse surveillance photos had revealed the fact that the Soviets and Cubans were also removing from crates and assembling for use a number of IL-28 jet bombers. The IL-28, though among the first jet bombers produced by the Soviet Union and originally designed and built in the late ‘40s, would be a massive upgrade to anything the Cubans had. Realizing he could no longer wait, JFK knew he had to start confronting the fact that the U.S. would very likely have to attack Cuba to remove the threat. In addressing the Ex Comm group he stated: “We are going to have to face the fact that, if we do invade, by the time we get to these sites, after a very bloody fight, they will be pointed at us. And we must further accept the possibility that when military hostilities first begin, those missiles will be fired.”

It was time to prepare for the worst. The military’s invasion preparations were stepped up and the President ordered the State Department to prepare a crash program to establish civil government for Cuba to be implemented after the invasion and occupation of the island nation.

Throughout the crisis and even before it had technically started the CIA had not been inactive. It was the Agency that had leaked the initial reports about the missiles in Cuba to Senator Kenneth Keating (NY) in late August and in September knowing that Keating would use these to embarrass the President. They had also leaked the reports to friendly media outlets and this was the source of the rumors about the missile sites before they were verified by the U-2 photos. And now, as the crisis was intensifying, certain members of the CIA were doing their best to exacerbate the situation to the point that Kennedy would be forced to invade. Fearing just such activity by the CIA, Kennedy had ordered the CIA to stop all raids and Op Mongoose type actions against Cuba. He wanted to ensure that no “mistakes” were made that would quickly expand into World War III. Those in the CIA’s anti-Cuba sector had other ideas however. In direct violation of Kennedy’s order the CIA’s Cuban point man Bill Harvey rounded up and equipped sixty anti Castro Cuban commandos and infiltrated them into Cuba in anticipation of the expected invasion. Someone in the CIA’s Miami station leaked this news to Robert Kennedy who promptly blew a gasket accusing Harvey of risking world nuclear war. Harvey retorted by stating that if the Kennedys had taken care of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs as they should have we would not be in this current mess.

On top of this Air Force Chief of Staff Curtis LeMay’s right hand man at the Strategic Air Command, General Tommy Power, had decided that he needed to raise SAC’s defense condition status to “DEFCON 2” in violation of the President’s order that the U.S. military be placed at DEFCON 3. (“DEFCON” simply refers to a gradient of defense readiness condition statuses ranging from DEFCON 5, which is normal readiness, to DEFCON 1, which is nuclear war imminent.) By raising to DEFCON 2 status, Power signaled to the Soviets that the U.S. was stepping up its war preparation, a signal that JFK did not want sent.

Between the actions of his own intelligence agency as well as his military to force his hand and the continued speed up of the Soviet construction of the missile sites, Kennedy’s position was becoming increasingly precarious. The chances of a “Guns of August” type mistake that would lead to planetary destruction were increasing by the hour…

To be continued…

Copyright © 2013

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved