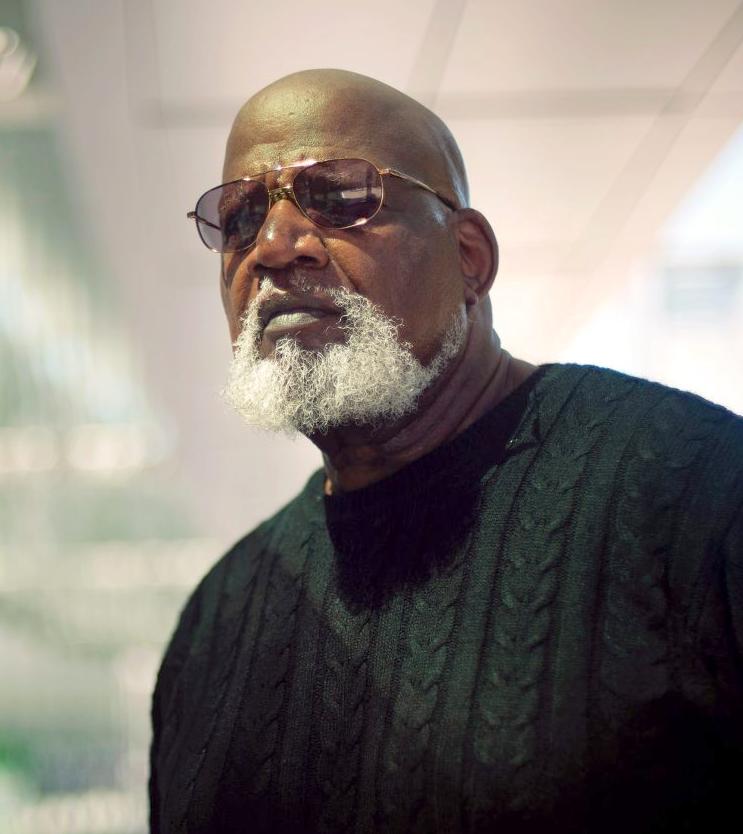

of the University of Washington Black Student Union,

March, 1970

Note: Presented here is Part II of “Hangin’ With the New Left,” a chronicle of my personal involvement with and observations of the New Left and Civil Rights protest movements on the University of Washington campus in the early 1970s. This installment covers the Black Student Union (BSU) protests against the University’s involvement in athletic competition with the Mormon run Brigham Young University (BYU) during the first two weeks of March, 1970. The BSU targeted BYU because at the time the Mormon Church did not allow Blacks in the clergy or participation in several other aspects of Mormon life. Through the protests they hoped to compel the University to sever its athletic ties with BYU. In light of today’s Black Lives Matter protests, I think this earlier era of Black protest is particularly relevant in understanding the antecedents to what is happening now. As this installment builds on information presented in the first installment of this series, I highly recommend reading it before diving in to Part II. For convenience I’ve linked that installment here: http://fromanativeson.com/2020/04/24/hangin-with-the-new-left-1970-part-i-the-seattle-liberation-front-by-mark-arnold/ With that understood, here is “Hangin’ With the New Left-1970-Part II-The Black Student Union Protests.” Please read on…MA

_______________________________________________

I couldn’t have known it at the time, but the Seattle Liberation Front demonstration at the Federal Courthouse[1] marked the beginning of what would be nearly three turbulent months of consistent student protest on the University of Washington campus. For the first couple of weeks after the TDA Courthouse demonstration I continued to attend Michael Lerner’s philosophy class, during which he didn’t speak much of the riot that I recall. For those two weeks things were calm and seemed normal. In the first week of March, however, that all changed. An on-campus group called the Black Student Union (BSU) announced that a demonstration would be held on Thursday, March 5th, the purpose of which was to protest the UW athletic department’s relationship with the Mormon run Brigham Young University (BYU). The BSU claimed that the University, by engaging in athletic contests with BYU, was sanctioning racism because certain tenets in the Mormon religion prohibited Blacks from joining the Mormon priesthood; from getting married in the Temple; from ascending to leadership positions in the church; and even, upon death, from access to the highest levels of the Mormon concept of heaven. In short, the BSU claimed that the Mormon Church considered Blacks to be spiritually inferior.

By March of 1970 protests of the Mormon run university by Black Student Unions on college campuses around the country had been building for a couple years. Like most UW freshmen, however, I’d never heard of them. I also had no knowledge of the Mormon faith whatsoever, and knew next to nothing about the BSU or what it stood for. Lerner never mentioned the group in our philosophy class, and from what I could tell there was no BSU presence at the TDA Courthouse protest. I did know by then that the main purpose of the Seattle Liberation Front was to mount a multi-dimensional movement aimed at several targets in American society: the Vietnam War; the poor and disenfranchised groups of people in the United States; and what they called the institutionalized racism and sexism prevalent in the country; the last of which was perfectly exemplified by Brigham Young University.

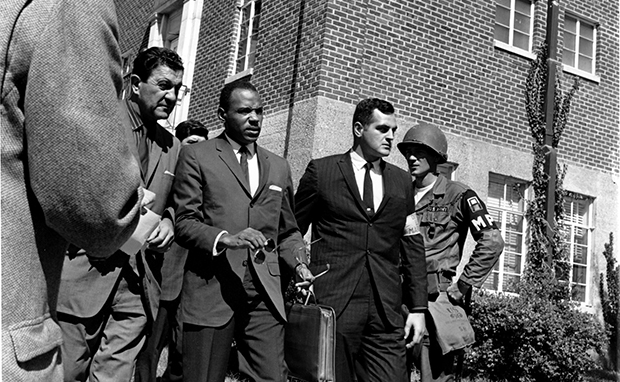

as he enrolls at “Ole Miss”, 1962

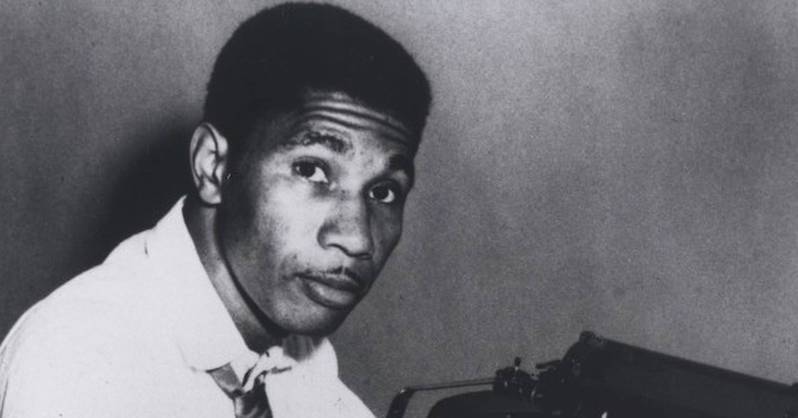

To understand the role of the Black Student Unions and how they came about, we need to look at some history. The roots of BSUs on college campuses in the late 1960s go deep into the mid-twentieth century Civil Rights movement in the United States, and even earlier, to the advent of slavery in the New World, the Civil War fought to at last resolve the issue of slavery, and the implementation of the repressive “Jim Crow”[2] laws in the South after the Civil War. What we call the “Civil Rights Movement”, which came about mostly as a direct challenge to the suppression of Blacks in the “Jim Crow” South, was actually comprised of a coalition of organizations, the oldest of which is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The NAACP was founded in 1909 in response to an epidemic of Black lynchings,[3] mostly in the South, but also extending into northern states such as Illinois. Focusing its efforts on the use of the court system to accomplish desegregation, the NAACP won several significant victories, including the landmark Brown vs. Board of Education case in 1954[4] and assisting James Meredith to integrate the University of Mississippi in 1962.[5] Through the late 1950s and early 60s the group also worked for voter registration and challenged segregation in public accommodations in the South, while lobbying Congress for civil rights legislation. During this time a number of NAACP members were murdered for their efforts, the most well known of which was Medgar Evers, who was shot and killed from ambush on his driveway in 1963.[6]

assassinated in 1963

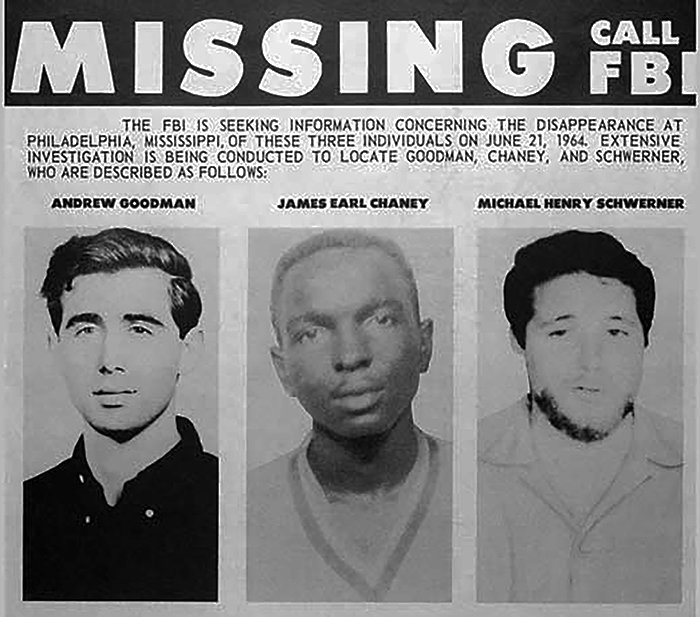

Another of the older groups involved in the Civil Rights movement of the 1940s, 50s and early 60s, was the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). With the advent of World War II many Blacks joined the armed forces and served honorably, but still faced racial barriers and injustice at home. In response to this, in 1942 CORE was formed and staged the first ever organized sit-in in Chicago, thus introducing the tactic that would be used many times in the movement’s future. Initially a northern group, by the early 1960s CORE had extended its reach into the South by organizing the famous Freedom Rides: an effort to desegregate the interstate bus lines by sending racially mixed groups of riders on extended trips to southern cities.[7] In the summer of 1964, while engaged in voter registration in Mississippi, three young CORE members, Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney, went missing. Their burned-out car was found two days later, but it took the FBI being called in and six more weeks before the bodies of the three murdered CORE members were recovered.[8] Meanwhile, the case became national news and did much to raise awareness of the Civil Rights issues still infecting the South.

in 1964, Andrew Goodman, James Chaney

and Michael Schwerner

The next major Civil Rights group of that time was the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which was formed under the leadership of Martin Luther King by a group of southern Christian ministers in 1957 following the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott. [9]Emphasizing the tactic of non-violent civil disobedience, the SCLC spearheaded civil rights campaigns across the South, but most famously in places like Birmingham and Selma, Alabama. The high point of the SCLC’s efforts took place on August 28, 1963 when over 200,000 people gathered in Washington DC for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, at which King delivered his historic, I Have a Dream speech.[10] The momentum generated for Civil Rights by King and the Civil Rights movement would, within a year, result in the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964.[11] After the Civil Rights Act, King and his followers, though still concerned with the South, increasingly focused their attention on northern cities like Chicago, taking on the more institutionalized racism in those areas.

March on Washington: “I have a dream…”

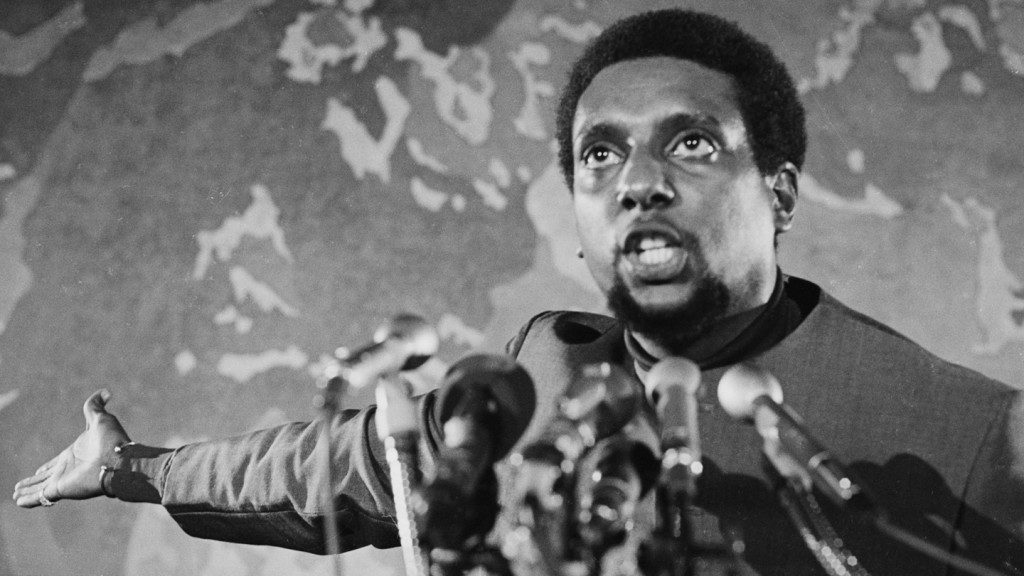

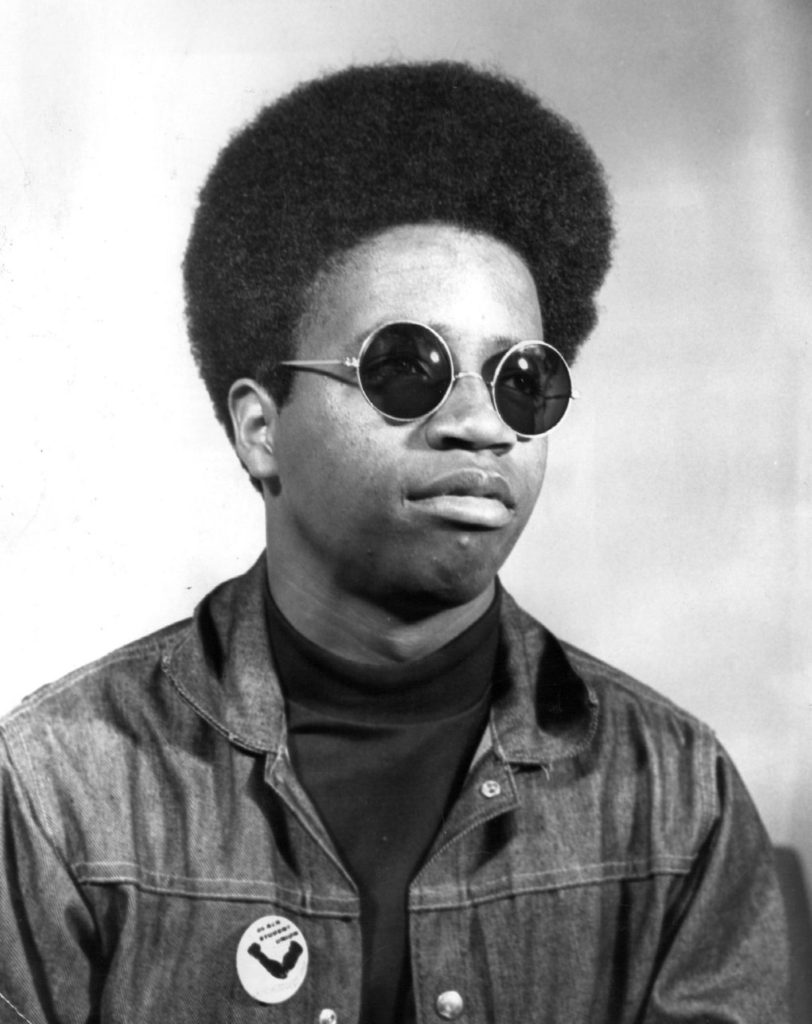

The last, and most recent, major Civil Rights group I’ll mention here is the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The SNCC was formed in 1960 by students involved in the movement who initially were, like the SCLC, dedicated to non-violence in their protests. Also active with registering voters in Mississippi in the summer of ’64, the SNCC took the bold step of forming the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party[12] as a challenge to the state’s all white delegation to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City that same summer. When the National Democratic Party failed to recognize the Mississippi Freedom delegation at the convention, instead recognizing the regular all white delegation, it was a major disappointment for two young SNCC leaders: H. Rap Brown and Stokely Carmichael. Over the next couple of years Brown and Carmichael would become increasingly disaffected with the mainline Civil Rights movement as run by King and the SCLC. Inspired by murdered Black Muslim leader Malcom X,[13] by 1967 both men were advocating for what they called “Black Power,” and had allied themselves with the Black Panther Party, founded in 1966 by Bobby Seale and Huey Newton.[14] The Panthers promoted a New Left political platform which included armed resistance by Blacks against what they viewed as white power structure oppression in their communities. Because of their SNCC leadership roles and their vocal advocacy of Black Power, by 1967 both Carmichael and Brown were well-known national figures and icons of the Black Power movement, as epitomized by the Black Panthers.

Stokely Carmichael ca. 1970

Stokely Carmichael’s national recognition as a leader of the SNCC and later the Black Power movement made him a prime candidate for speaking engagements to Black communities and students all over the country. A couple of those speeches took place in Seattle on April 19, 1967, when Carmichael gave a talk to 3,000 students at the University of Washington and, astoundingly, to 4,000 students, civil rights workers and interested citizens later that evening at Seattle’s Garfield High School. Carmichael used the talks to relay his message, telling his audiences that, “It’s a new day for African-Americans…You have tried so hard to be white that you have gone to Tarzan movies and applauded as Tarzan beat up your black brothers. We have been brainwashed.”

Carmichael’s speeches in Seattle inspired the young Blacks in attendance. His message of “Black Power;” essentially that Blacks needed to control the institutions and resources in their own communities for their own benefit, resonated with them. Two of these people, E.J. Brisker and Eddie Demming, who would be among the founders of the BSU at the University Washington in early 1968, credit Carmichael with catalyzing their activism, stating that, “(Carmichael) had something we could identify with. He told us that things could no longer stay the same.”

Seven months after Carmichael’s talks in Seattle, on Thanksgiving weekend of 1967, Civil Rights activist and Sports Sociologist Dr. Harry Edwards [15] of San Jose State University held a Black Youth Conference in Los Angeles, attended by young Blacks from up and down the west coast, including several from the University of Washington. Many of the Black political philosophies and groups were represented there, including Black Nationalists, Black Socialists and the Black Panthers. It was at this conference that several prominent Black athletes, including Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (then known as Lew Alcindor)[16], announced they would be boycotting the Olympic Games in Mexico City[17] the following summer to protest U.S. racism. Also discussed at the conference was the concept of Black Student Unions on college campuses. When the UW students returned to Seattle after the conference, they brought the idea of Black Student Unions with them, and by early 1968 had founded the University of Washington BSU.

Shortly after its creation, the BSU announced itself and its intentions in a published article entitled, “New Black Image Emerging.” The article stated that the BSU intended to, “…create a power base from which to present certain demands to the University administration.” The demands would have three main objectives: increased minority enrollment, the hiring of more minority faculty, and the creation of a Black Studies program. The article also expressed the BSU’s intention that it would not be exclusively a Black group, but would also be open to Native Americans and Hispanics; essentially all people of color. The last point the article addressed was the question of how militant the group would be in its demands. This was answered by the statement that the BSU hoped to work in cooperation with the school administration to accomplish its aims; but, as one founding BSU member, Larry Gossett,[18] put it: “Our militancy is entirely dependent on the white reaction to the concrete proposals we make.” In early March, 1970, we were about to find out just what Gossett’s statement meant.

Larry Gossett ca. 1970

By that time few of us knew that the UW BSU and the school administration had been engaging in a “dialog” about the BYU matter for several months. One cold January afternoon in 1970, as the Husky gymnastics team was preparing for a competition against BYU, about 20 BSU members entered Hec Edmunson Pavilion, where the team was warming up, and proceeded to dump garbage and spill catchup and oil all over the gymnastics mats. When challenged by the UW gymnastics coach they responded by throwing a pail of water in his face before leaving the building. Around the same time Lynn Hall, a black student gymnast at the UW, started circulating a petition requesting that the University discontinue future athletic competitions with BYU. A week later UW Athletic Director, Joe Kearney, started his inquiry into the BYU matter to determine if the UW should continue its athletic relationship with the Mormon University.

A month went by. The TDA riot at the Federal Courthouse happened on 17 February, but there was still no word from Kearney. Two days later, on 19 February, the BSU issued a statement in which they demanded a decision from Kearney and the school administration by March 5th. If Kearney and the administrators failed to act by that time, the BSU would then take matters into their own hands and “act accordingly.” On February 27th Kearney issued a letter to the BSU stating that, due to the number of meetings and interviews that were still required to resolve the BYU issue, it would be impossible to meet the March 5th deadline. On March 4th the BSU responded to Kearney in a letter published in the campus newspaper, the UW Daily, which stated that Kearney had been, “allotted adequate time for a decision on BYU,” and that they would now “act accordingly” to resolve the matter. Thus, the stage was set for the March, 1970 Black Student Union protests on the University of Washington campus.

on the University of Washington campus

as it looks today

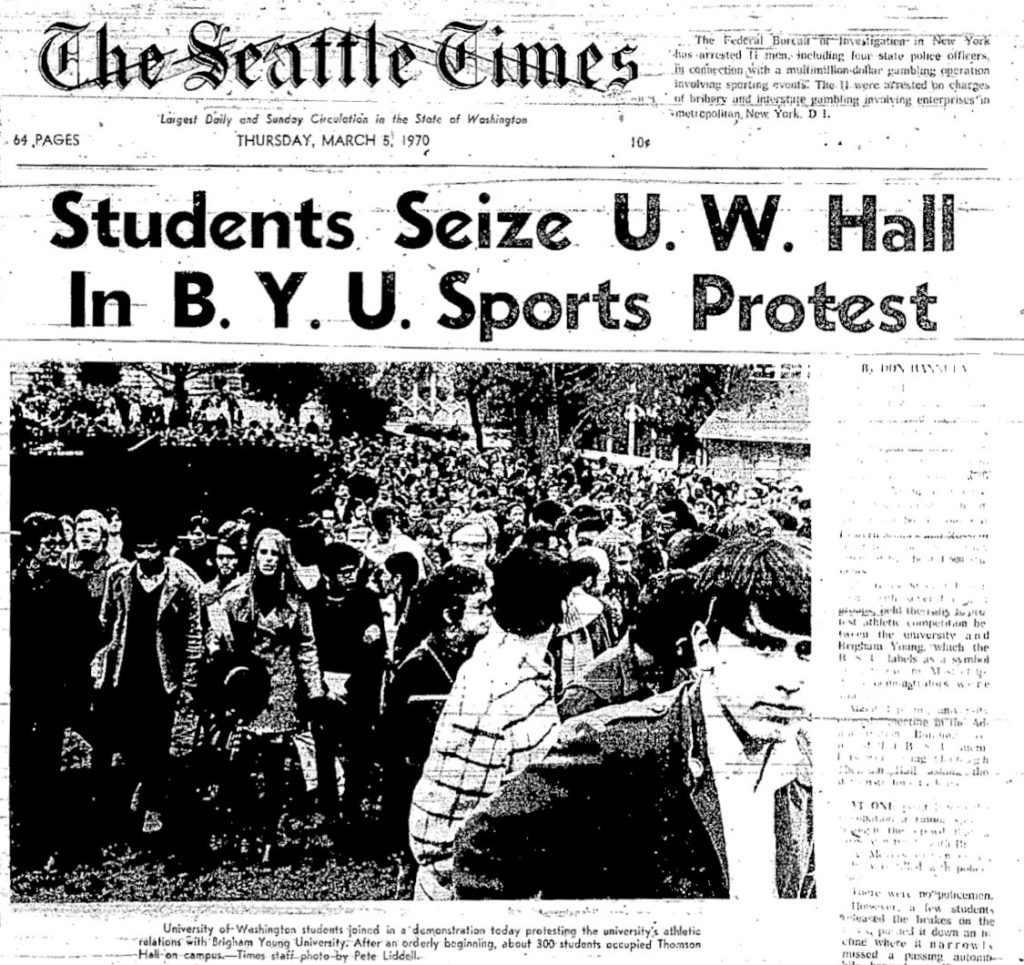

On a cool and overcast Thursday, March 5th, 1970, the UW BSU, with marginal assistance from the SLF, organized the first large, on campus student protest of the UW’s ongoing athletic arrangement with BYU. On that day about 1000 student protesters gathered around noon at the Husky Union Building (HUB), and after a couple of speeches, marched to the UW Administration building where ten BSU leaders met with University Vice President Dr. John Hogness,[19] who told them there was no way the University could decide on the BYU matter prior to April 1st. The frustrated leaders then led the protesters to Thomson Hall, an empty academic building close to the HUB, and proceeded to occupy it. Within a few minutes the protesters had placed two banners on the outside of the building, one of which labeled it “Occupied,” while the other re-named it “Marx Hall.” According to Larry Gossett, one of the prominent BSU leaders, the demonstrators intended to stay in the building until, “…the university reevaluates its position on the BYU issue.” Within an hour or so, however, after the BSU decided to give the UW administration one more day to decide, the protesters packed up and abandoned the building.

first day of BSU demonstrations.

Looking back, I remember all this like it was yesterday. Thomson Hall wasn’t much more that a stone’s throw from the HUB, where I often ate my lunch in those days. Thus, as the protesters marched toward the Admin building, I was with them; and so was there as the BSU leaders spoke to Hogness, and later as we occupied Thomson Hall. Fully expecting the cops to come and try to evict us from the building, we all donned bandanas as tear gas protection and barricaded the doors with desks and chairs from the classrooms. It had only been a few weeks since the Federal Courthouse riot, yet once again there I was, preparing to confront the police; this time intentionally.

It was a relief to me when, after the BSU leaders agreed to give the school administration another day to make their decision on BYU, we all departed Thomson Hall. What would have happened had the cops actually come to evict us from that building? Would I have stayed and fought it out? I’m glad I didn’t have to make that decision, but I think I probably would have. My pride would have dictated it, if nothing else. The truth is, however, it was far easier for me to commit to the BSU protests than to Lerner’s radical New Left ideas because I felt in my heart that racism was wrong and should be protested, wherever it was encountered. It was much more visceral for me than Lerner’s intellectual approach, as I was experiencing in his philosophy class. The ideas he presented, drawn from the works of Marx, Hegel and Marcuse, ran counter to the American middle class ideals I was raised with; and those ideals weren’t dying easy.

BSU protest on March 5th, 1970

Opposing racism, however, encountered no such intellectual barriers for me. As a kid growing up in a white, south Seattle middle class superb, racism was never an issue that confronted us directly, so we never had to deal with it. As I recall, we only had one Japanese kid in our entire elementary school, and no Blacks. The Japanese kid’s name was Dean Kiyohara and he was a personal friend to me and to many of the other kids I hung out with. Dean may know differently, I haven’t spoken to him about it, but no one that I knew ever held his Japanese ancestry against him, even though we were less than a generation removed from World War II. In the household I grew up in, neither of my parents spoke disparagingly of other races, so I had no cultural or home “educational” factor that disposed me towards racism. My first encounter with a Black student in a school I attended didn’t happen until high school, and I observed no discrimination against that person from any of the students or teachers. As I moved through my Jr. High and High School years, which was from about 1963 to 1969, I was well aware of the Civil Rights movement as it gained steam in the South, but that didn’t seem to affect us much in Seattle. That’s how it seemed.

Then, starting in the spring of 1969, I began dating a girl named Sue Hegwood. I’d known Sue since kindergarten, but it wasn’t until we started our relationship that I really got to know her. Sue was raised in a family much more liberal and socially aware than mine, and so was much more alert to the insidious aspects of racism. She and I would often have long talks deep into the night, sharing our thoughts on everything, especially social issues and civil rights, and it was through her and those talks that I began to coalesce my ideas on racism. Thus, by the time of the BSU protests at the UW in the spring of 1970, I was very receptive to the message. The thing that bothered me about racism, I had decided, was the injustice of it. And I was most definitely opposed to injustice.

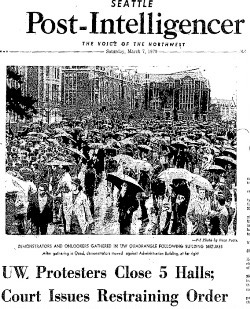

BSU protest on Friday, March 6th, 1970

The BSU protests would continue on campus for the better part of the next week. On Friday, March 6th, with no indication there would be a response from Hogness, another rally was held at the HUB followed by another march around campus. I was not personally involved in this protest, but did witness the change in tactics employed by the BSU leadership when one of my classes was interrupted by several of the protesters who barged in and ordered the professor to stop his lecture and all the students to leave. It took me a moment to comprehend: were the BSU protesters actually shutting down my class? Indeed, they were. The same method was used in other classes as well, with the protesters staying for around 10 minutes before departing and then interrupting another class. This new tactic was particularly troubling for the school administration, as it resulted in many complaints from students and professors, who simply wanted to do what they were there to do. I must admit, though my heart was with the cause of the BSU protesters, I thought the interrupted students and professors had a valid complaint. Despite my sympathy for the cause, I did not like the new methods being employed by the BSU.

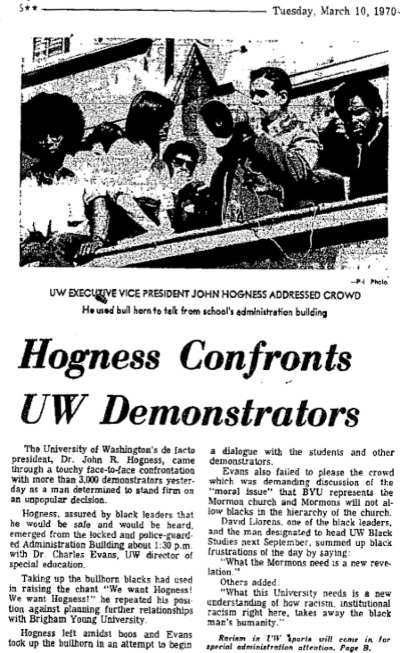

The protests did not hinge on my thoughts or participation, however. After the first two days of campus unrest Hogness obtained a court restraining order that prohibited the BSU, the SLF and/or any other group “…acting in concert from employing force or violence, or the threat of force or violence, against persons or property on plaintiff’s premises.” He then had the text of the restraining order published in “The Daily”, on Monday, 9 March. In addition to this both of Seattle’s major daily newspapers, the Seattle Post Intelligencer and the Seattle Times, published editorials sympathetic to the BSU’s goals and blamed the disruptive protest tactics on the Seattle Liberation Front; a claim that was nothing short of a bald-faced lie. Most likely the papers, not wanting to be accused of being racist themselves, chose the expedient of targeting the SLF, which was in fact only marginally involved, and certainly not in a leadership capacity. In that way, the newspapers could appear to be supporting civil rights and yet opposed to the disruptive protest tactics.

Vice President Hogness addressing

protesters from the Admin Building

Over the weekend of March 7th and 8th, Vice President Hogness conferred with the UW Board of Regents on the BYU matter, and at last established the University’s position regarding the Mormon school. That position, which Hogness announced on Sunday, March 8th, stated that the University would honor its existing athletic contracts, but would undertake no future contracts for athletic competition with BYU. He also stated that no student athlete would be required to participate in competition against BYU if his conscience dictated otherwise. Needless to say, the BSU was not impressed with Hogness’ statement, and in response, on Monday, 9 March, called for another huge demonstration to protest the University’s unwillingness to sever the BYU relationship. This time an estimated 3500 students gathered at the HUB and marched to the administration building where BSU leaders once again intended to meet with Hogness. Upon arrival, however, they found the building locked down and protected by police in full riot gear. It took about 20 minutes, but finally Hogness addressed the crowd of protesters, stating much the same as his Sunday announcement.

As you might expect, the BSU wasn’t having any of what Hogness was serving up; and two days later, on Wednesday, 11 March, they unleashed their response. Once again the protest started with a rally at the HUB. After a couple of speeches decrying the University’s unwillingness to do anything about the obvious racism displayed by its BYU involvement, about 700 protesters disbursed across the campus and briefly took over eight different academic buildings. Once inside the buildings the protesters used the same tactics of ordering the students to leave and shutting down the classes. This time, however, the students and professors put up more resistance, with the result that 14 of them were injured in dust ups with the protesters. Following the occupations, the protesters re-formed and again marched on the Admin building. Once there Hogness told them they immediately needed to cease and desist or, with the restraining order still in force, risk being arrested and cited for contempt of court. A short while later the cops arrived on the scene, but by then the protesters had disbursed, and no one was arrested.

Immediately after Wednesday’s protest the University launched an investigation into the violence students had been subjected to with the intention of having the perpetrators arrested. Depositions were taken from injured students and professors and photos of students and BSU members were studied, but identifying the guilty parties proved to be very difficult, and no arrests resulted from the investigation. Meanwhile, however, Vice-President Hogness had seen enough. The next day, Thursday, March 12th, he didn’t wait for the protest to go violent before bringing in the police; he made sure they were there from the get-go. Starting that morning, squads of King County Sheriff’s officers and Seattle cops patrolled the campus, and continued to do so all day. The BSU held another noon rally at the HUB, but chose not to directly confront the police. In a talk to the crowd one of the BSU’s most vocal leaders, Carl Miller, explained the BSU’s position:

“(The) University has shown us its true nature. They are morally bankrupt, politically inept and ‘Pigs,” Miller said. “We don’t have to love our enemy,” he continued, “but we do have to respect him. Respect him for what he is—a vicious, murderous, lying, treacherous pig dog. And anybody here, who believes that those policemen that they got out there will not kill you, is in for a rude awakening. We do not intend to commit suicide. We do not intend to place our bodies in front of his guns and billy-clubs. The effect of that we’ve seen over and over again; people get hurt, and nothing changes.”

I was in the crowd that day, and from the distance of a few feet witnessed Carl Miller making those comments. I admired his leadership and courage, but was having difficulty understanding the vitriol towards the police expressed by his words. I felt the same when I heard the White SLF protesters calling the police “Pigs” at the Courthouse protest a few weeks earlier. To me such language was self-defeating; good for rabble rousing and inciting conflict perhaps, but bad for raising understanding and sympathy for the cause. Of course, as a White, middle class kid from the suburbs, I lacked the experience of a Black kid growing up in his neighborhood under the watchful eye of a predominantly White and possibly racist police force. It is an accurate observation that people who have experienced an injustice, no matter how slight, tend to want to get even. Maybe that explains the antagonism Miller and other Blacks voiced in their rhetoric, but it certainly doesn’t explain that of the White radicals, who, like Michael Lerner, as often as not had privileged upbringings. Either way, to me the language of the protest often conflicted with, and inhibited, its purposes.

As it turned out, that Black Student Union rally at which Carl Miller spoke would be the last of the anti-BYU protests on the UW campus, not just for that spring, but forever. The next day, Friday, March 13th, winter quarter finals ended and the campus emptied for spring break. To that point the BSU demonstrations had been the largest and most disruptive in the University’s long history, and in their wake the school’s administration was hit with a huge backlash from aggrieved faculty, students, and alumni who felt that Vice President Hogness and the administration should have taken a stronger stand against the protesters. Twenty-three faculty of the History department signed a letter to Hogness decrying his lack of action, stating that the demonstrations exposed “the students, the staff, ourselves, our books, manuscripts and papers to serious jeopardy.” Sounding much like a current FOX News broadcast critical of today’s Black Lives Matter protests[20] across the country, UW English professor Edward Alexander penned a letter to Hogness complaining that, “…a mob has been allowed, during a period of several days, to roam unhindered from building to building, disrupting classes, destroying books and manuscripts in offices and libraries, and brutally beating students who attempted to resist.” He went on to say that with its lack of appropriate response to the demonstrators the University opened wide “the floodgates to anarchy and to its natural sequel, tyranny.” If you’ve been listening at all to today’s news, that should certainly sound familiar.

I think I expected that the BSU anti-BYU protests would probably pick up where they left off when we returned to campus for the spring quarter of 1970. Strangely, even after the school administration delayed acting on a motion to sever relations with BYU on April 10th, nothing much happened. The motion eventually died due to neglect, and a year later the University renewed its athletic competition contracts with the Mormon school. It would take another eight years before the matter was ultimately resolved, surprisingly by the Mormon Church itself, when in 1978 it at last revised its doctrine and allowed Blacks into the priesthood, to be married in the Temple, and to be worthy of attaining the Mormon concept of heaven. Would that have ever happened without the Black Student Union protests at the UW and at other campuses around the country? Possibly, but I believe it certainly would have taken much longer.

Even if the BSU protests had continued that spring, however, they very soon would have been eclipsed by another major event. On April 28th, 1970, President Richard Nixon ordered U.S. ground troops in Vietnam to invade the neighboring country of Cambodia, and almost immediately, all hell broke loose on college campuses around the country…

To be continued…

Copyright © 2020

By Mark Arnold

All Rights Reserved

[1] The story of the Seattle Liberation Front and the Seattle Federal Courthouse protest of February 17th, 1970, also called “The Day After” (TDA) protest due to the fact it took place the day after the Chicago 7 defendants were sentenced, is covered in full in Part I of this series, which I’ve linked here: http://fromanativeson.com/2020/04/24/hangin-with-the-new-left-1970-part-i-the-seattle-liberation-front-by-mark-arnold/ For more complete understanding, Part I should be read prior to Part II…MA

[2] “Jim Crow” was a derogatory term for a Black person that started in the 1830s, most likely from a popular song and dance called “Jump Jim Crow” which was performed in “black face” at the time by a white comedian named Thomas Dartmouth Rice. The song was supposedly inspired by a disabled Black slave named Jim Cuff or Jim Crow. (I have encountered other explanations for the term, but this one is the most plausible to me.) “Jim Crow” laws were laws passed in the Southern States following the Reconstruction period after the Civil War, the purpose of which was to ensure the continuation of a White dominated society and culture in the South by the denial of Human Rights to the now freed Blacks living there. The “Jim Crow” system dominated in the South from about the late 1880s until the mid 1960s.

[3] Of all the suppressive tactics employed in the “Jim Crow” South against Blacks, the most horrifying by far was the practice of kidnapping and hanging Black people, otherwise known as “lynching.” During the “Jim Crow” era an estimated 4,000 lynchings took place in the South, most perpetrated by elements of the terrorist organization known as the Ku Klux Klan. The last reported lynching of a Black person by Klan members took place in 1981.

[4] Handed down in May, 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segregated schools are otherwise equal in quality. One of the main NAACP attorneys on the case was future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall.

[5] James Howard Meredith (born June 25, 1933) is a Civil Rights Movement figure, writer, political adviser and Air Force veteran. In 1962, he became the first African-American student admitted to the segregated University of Mississippi, after the intervention of the federal government, an event that was a flashpoint in the Civil Rights Movement. Inspired by President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address, Meredith decided to exercise his constitutional rights and apply to the University of Mississippi. His goal was to put pressure on the Kennedy administration to enforce civil rights for African Americans.

[6] Medgar Wiley Evers (July 2, 1925 – June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist in Mississippi, the state’s field secretary for the NAACP, and a World War II veteran who had served in the United States Army. He worked to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi, end the segregation of public facilities, and expand opportunities for African Americans, which included the enforcement of voting rights. Evers was assassinated in 1963 by Byron De La Beckwith, a member of the White Citizens’ Council in Jackson, Mississippi. This group was formed in 1954 in Mississippi to resist the integration of schools and civil rights activism. As a veteran, Evers was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. His murder and the resulting trials inspired civil rights protests; his life and these events inspired numerous works of art, music, and film. All-white juries failed to reach verdicts in the first two trials of Beckwith in the 1960s. He was convicted in 1994 in a new state trial based on new evidence.

[7] The Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions which ruled that segregated public buses were unconstitutional.The Southern states had ignored the rulings and the federal government did nothing to enforce them. The first Freedom Ride left Washington, D.C. on May 4, 1961, and was scheduled to arrive in New Orleans on May 17

[8] The three murdered CORE members, James Chaney from Meridian, Mississippi, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, from New York City, had been working with the Freedom Summer campaign in 1964 by attempting to register African-Americans in Mississippi to vote. This registration effort was a part of contesting over 70 years of laws and practices (Jim Crow) that supported a systematic policy, begun by several states in 1890, of disenfranchisement of potential black voters. The three men had traveled from Meridian to the community of Longdale to talk with congregation members at a black church that had been burned. The trio was thereafter arrested following a traffic stop outside Philadelphia, Mississippi for speeding, escorted to the local jail, and held for several hours.As the three left town in their car, they were followed by law enforcement and others. Before leaving Neshoba County, the car was pulled over and all three were abducted, driven to another location, and shot at close range. The three men’s bodies were then transported to an earthen dam where they were buried. The disappearance of the Civil Rights workers resulted in a months long FBI investigation to crack the case, as well as front page and nightly news casts about the missing CORE members. The movie “Mississippi Burning” (1988) is a dramatization of the events regarding the murders of the three Civil Rights workers.

[9] The Montgomery Bus Boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a seminal event in the Civil Rights movement. The campaign lasted from December 5, 1955 — the Monday afterRosa Parks, an African-American woman, was arrested for refusing to surrender her seat to a white person — to December 20, 1956, when the federal ruling Browder v. Gayle took effect, and led to a United States Supreme Court decision that declared the Alabama and Montgomery laws that segregated buses were unconstitutional. The Montgomery Bus Boycott marked the ascent of Martin Luther King to a leadership role in the Civil Rights Movement.

[10] “I Have a Dream” is a public speech that was delivered by American civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom on August 28, 1963, in which he called for civil and economic rights and an end to racism in the United States. Delivered to over 250,000 civil rights supporters from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech was a defining moment of the civil rights movement and among the most iconic speeches in American history.

[11] The Civil Rights Act of 1964 (enacted July 2, 1964) is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requirements, and racial segregation in schools, employment, and public accommodations. The legislation had been proposed by President John F. Kennedy in June 1963, but it was opposed by filibuster in the Senate. After Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed the bill forward. The United States House of Representatives passed the bill on February 10, 1964, and after a 54-day filibuster, passed the United States Senate on June 19, 1964. The final vote was 290–130 in the House of Representatives and 73–27 in the Senate.After the House agreed to a subsequent Senate amendment, the Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Johnson at the White House on July 2, 1964.

[12] The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), also referred to as the Freedom Democratic Party, was an American political party created in 1964 as a branch of the populist Freedom Democratic organization in the state of Mississippi during the Civil Rights Movement. It was organized by Black Americans and Whites from Mississippi to challenge the established power of the Mississippi Democratic Party, which at the time allowed participation only by whites, when Black Americans made up 40% of the state population.

[13] Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965), was a Black American minister, and human rights activist who was a popular figure during the civil rights movement of the mid 1960s. He is best known for his time spent as a vocal spokesman for the Nation of Islam, then led by Elijah Muhammad. In the 1960s, Malcolm X began to grow disillusioned with the Nation of Islam, as well as with Elijah Muhammad. He subsequently embraced Sunni Islam (the largest denomination of Islam, followed by 90% of Muslims around the world) and the Civil Rights movement. After completing a pilgrimage to Mecca and a brief period of travel across Africa, he publicly renounced the Nation of Islam and founded the Islamic Muslim Mosque, Inc. (MMI) and the Pan-African Organization of Afro-American Unity(OAAU). Throughout 1964, his conflict with the Nation of Islam intensified, and he was repeatedly sent death threats. On February 21, 1965, he was assassinated while giving a speech. Three Nation members were charged with the murder and given indeterminate life sentences. Speculation about the assassination and whether it was conceived or aided by leading or additional members of the Nation, or with law enforcement agencies, have persisted for decades after the shooting.

[14] The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP) was founded in 1966 in Oakland, California by college students Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale. It was a revolutionary organization with an ideology of Black nationalism, socialism, and armed self-defense. Both Seale and Newton ultimately became icons of the New Left; Newton after being arrested in 1967 for a shoot-out in which a police officer died, and Seale after he was bound and gagged by the judge during the trial of the Chicago 8 following the Anti-War protests in Chicago during the Democratic Convention in the summer of 1968. In Newton’s case the slogan “Free Huey” became a rallying cry for the New Left at the time; and Seale was immortalized in the song “Chicago” by singer/songwriter Graham Nash.

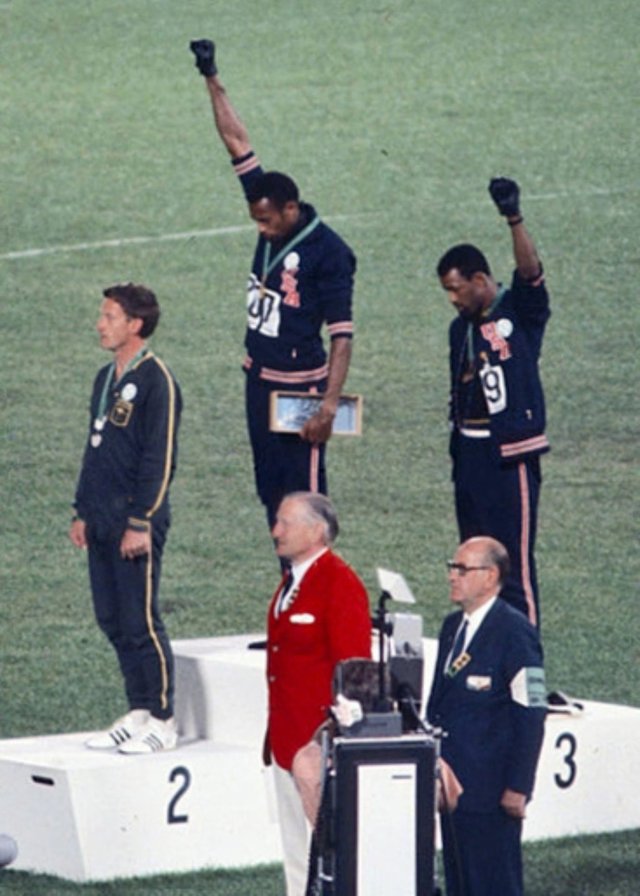

[15] Dr. Harry Edwards (born November 22, 1942) is an American sociologist and Civil Rights activist. He completed his PhD at Cornell University and is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Edwards’ career has focused on the experiences of African-American athletes. Edwards’ career has focused on the experiences of African-American athletes and he is a strong advocate of black participation in the management of professional sports. He has served as a staff consultant to the San Francisco 49ers football team and to the Golden State Warriors basketball team. He has also been involved in recruiting black talent for front-office positions in major league baseball. Author of The Revolt of the Black Athlete, Himself a former discus thrower, Edwards was the architect of the Olympic Project for Human Rights which led to the Black Power Salute protest by two African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, both San Jose State College athletes, at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

[16] Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr.; April 16, 1947) is possibly the most dominant College andProfessional basketball player of all time. At UCLA the 7’1” center was a three time All American and won three consecutive NCAA titles. He then played 20 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the Milwaukee Bucks and the Los Angeles Lakers. During his career as a center, Abdul-Jabbar was a record six-time NBA Most Valuable Player (MVP), a record 19-time NBA All-Star, a 15-time All-NBA selection, and an 11-time NBA All-Defensive Team member. A member of six NBA championship teams as a player and two more as an assistant coach, Abdul-Jabbar twice was voted NBA Finals MVP. In 1996, he was honored as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History. NBA coach Pat Riley and players Isiah Thomas and Julius Erving have called him the greatest basketball player of all time. He has long been an ardent advocate of full Civil Rights for Blacks and has frequently been outspoken on the matter.

Tommy Smith: Black Power salutes at ’68

Mexico City Olympics

[17] The 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games became famous for two things. The first is U.S. Olympian Bob Beamon’s unbelievable record setting long jump of 29 ft. and 2 ½ inches, nearly 2 ft. more than the prior record; an unheard-of margin. It would take another 23 years for Beamon’s record to be broken. The second reason is that it was at the Mexico City Games that John Carlos and Tommy Smith, two Black American sprinters, during a medals ceremony, stood on their pedestals displaying the clenched fist, Black Power salute as the United States national Anthem was being played. The photo of Carlos and Smith with their clenched fists is one of the historic images of the U.S. Civil Rights era.

[18] Larry Gossett (born 1945) is an American politician and activist from Seattle. He was a member of the nonpartisan King County Council representing District 2 from 1993 to 2019 and served as chair of the Council in 2007 and 2013.A life-long advocate of Human and Civil Rights, Gossett became a founder of the Black Student Union on the UW campusand helped to organize nearly a dozen high school and middle school Black Student Unions throughout Seattle. As a student activist, he was instrumental in bringing about the UW’s Educational Opportunity Program minority recruitment program. He graduated from the UW in 1970, receiving the university’s first-ever degree in African American studies. Before he had even formally received his BA he became the first supervisor of the Black Student Division in the university’s Office of Minority Affairs. The Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project describes him as having been, in the late 1960s, “one of Seattle’s best known young black radicals.”

[19] At the time of the BSU protests long time UW President Dr. Charles Odegaard was travelling Europe, thus the unhappy task of dealing with the protests fell to Dr. Hogness.

[20] Black Lives Matter (BLM) is an organized movement advocating for non-violent civil disobedience in protest of incidents of police brutality against Black American people. Over 30 chapters of the BLM exist in the United States and worldwide. With the recent killing of an American Black man named George Floyd by a Minneapolis policeman, BLM protests have erupted across the U.S. with sympathetic protests taking place around the world. The protests are ongoing at the time of this writing.

2 Responses

BLM is, at its core , a Marxist revolutionary organization. The vast majority of its supporters , blinded by legitimate ,rage against actual injustice , are mobilized to eliminate , not the worst of America but the best of America. The co opting of legitimate protest to serve an obscured agenda is once again manifesting . A clear differentiation is required that the moral legitimacy of the real protest not be warped to serve a covert and malignant agenda. Let the pent up energy ,born of legitimate outrage ,be released in the service of freedom and equality rather than being redirected to the counter productive Marxist agenda.

Thanks, Roger! Your point is very well made. The development of the “New Left”, as opposed to what was historically merely the “Left,” or basically classic Marxism, centered around the realization that the traditional “working class” model of Marxism wasn’t workable in the West, and the US particularly, because of the development of a prosperous middle class which rendered them immune to the charms of the Marxist-communist standard working class approach. With that realization came a shift by the Marxists toward targeting the more disenfranchised of the Western society, those who were subject to racism and economic deprivation, as well as the 3rd world peoples involved in throwing off their colonial shackles. This was a distinct policy shift by them, heavily promoted by Herbert Marcuse among others in the post World War II early Cold War era. The early MLK Civil Rights movement up until about the 1963 March on Washington did not promote or endorse Marxist ideals, even though that is what they were being accused of by Hoover’s FBI. By 1965 this was starting to change, as Rap Brown, Stokely Charmichael and the Black Panthers, which group adopted a thoroughly New Left platform, came on the scene. With MLK’s assassination, the co-opting of the Civil Rights movement by the Marxists became nearly complete. I think this was primarily accomplished through the infiltration of the Universities, where the New Left principles were taught to the impressionable students, both Black and White, through the writings and teachings of Marcuse and others, who had basically updated Marxism to the current situation. By the time of my experiences written here, the classic Civil Rights movement no longer existed, instead having morphed into variations of the “Black Power” theme while espousing New Left principles. The BLM we are witnessing today is the next generation outgrowth of that scene. That is what I see as I understand it now. Thanks for posting your thoughts. I always find your views engaging. L MA